Aubrey

Rickards:

winged pioneer

Wing Commander Aubrey Rickards (1898—1937)

holds a distinctive place in the annals of British penetration

of southern Arabia. But his role is not widely known; he did not

live to tell the tale. In 1937 he was killed in an air crash in

southern Oman. He was 39, and had already had an eventful

career, winning the Air Force Cross for gallantry in

Transjordan, and, as we shall see, the OBE. for services in

Aden.

Rickards was the son of a Gloucestershire farmer, and was a

student at the Royal Agricultural College, Cirencester, when the

First World War broke out. He enlisted in the Royal Flying Corps

and, after training as a pilot, was sent to France in 1917; a

fortnight later his plane was shot down and he spent the rest of

the war as a prisoner in Germany.

His post-war service in the Royal Air Force was spent mainly

in the Middle East, including seven years in Aden, and three

years in Iraq and the Gulf.

|

The Tiger Moth

in which Rickards flew many sorties into the hinterland of

Aden.

Photograph: A R M Rickards; courtesy James Offer |

Rickards’ initial posting to Aden, as a Flight Lieutenant,

was from 1922—23. It whetted his interest in Aden’s little

known hinterland, and also in the Horn of Africa where he spent

several weeks on safari in Somaliland. In 1922, Ras Tafari,

later Emperor Haile Selassie, visited Aden, and it fell to

Rickards to give him his first experience of flying. The young

Prince Regent invited Rickards to visit Abyssinia. Three years

later Rickards found the opportunity to do so, organising and

leading a six month hunting and filming expedition through

western Abyssinia to the Sudan. He wrote a lively account of

this for The Sphere, which included a graphic description

of his close and nearly fatal encounter with a bull elephant.

In March 1928 Rickards returned to Aden [see

map] as RAF Intelligence

Officer and was to remain there for the next five years. His

arrival coincided with the assumption by the RAF of

responsibility for the defence of Aden and its Protectorate.

Since 1919, Imam Yahya, who claimed sovereignty over the whole

area, had refused to recognise the boundary between Yemen and

the Protectorate delimited by an Anglo-Turkish Commission in

1903—5, and his forces had steadily encroached on territory

claimed by the British. In the Dhala area, Zaidi encroachment

had reached a depth of 30 miles, bringing the nearest Zaidi post

to within 50 miles of Aden. Without massive military

reinforcements, the British in Aden were powerless to repel this

intrusion. However, the air power provided by the increased RAF

presence in 1928 (a squadron of 12 aircraft instead of a ‘flight’

of six) was soon to reverse the tide of Zaidi encroachment. In

February that year, the commander of the Zaidi garrison in Qa’taba

contrived the abduction of two shaikhs from within the

Protectorate. The British retaliated by bombing Zaidi border

garrisons until, in March, the two captives were released. A

temporary truce with the Imam followed, and Major (later Sir

Trenchard) Fowle, the Assistant British Resident, accompanied by

Sultan Abdul Karim Fadhl of Lahej, travelled overland to Taiz to

discuss a possible basis for a political settlement. Rickards

went with them as far as Musaimir on the border; Fowle had

wanted to take him all the way but thought that the presence of

an RAF officer might prove unwelcome to the Taiz garrison

commander, Ali al-Wazir. Later, the Imam asked for the truce to

be extended until the middle of July, to which the British

agreed on condition that the Imam’s forces evacuated Dhala by

20 June. The deadline passed, and warning leaflets dropped by

the RAF over Yemeni towns went unheeded. Bombing of Zaidi border

garrisons was resumed, and later extended to include military

targets in Taiz, Dhamar, Ibb and Yarim. This activity spurred

Qutaibi tribesmen to attack and expel the Zaidi post at Sulaik,

south of Dhala. Their success raised morale within the

Protectorate where previously panic had reigned due to rumours

of an imminent Zaidi advance on Lahej.

On 7 July Rickards was instructed to proceed to Sulaik to set

up a forward intelligence post and make contact with the Amir of

Dhala, Nasr bin Shaif. The latter had spent the past eight years

in exile in Lahej but was now mobilising a force of Amiri and

Radfani tribesmen to advance on Dhala under cover of the RAF. On

14 July the Amir, at the head of his improvised and turbulent

army of some thousand tribesmen, accompanied by Rickards with an

escort of fifty Lahej troops under the command of Ahmad Fadhl

Al-Abdali, succeeded in capturing Dhala.

Rickards and his W/T operator, Aircraftman Smith, installed

themselves in Dhala fort, where they were later joined by Hassan

Muhammad, a Residency interpreter sent up by Fowle to assist

Rickards in his intelligence and liaison role. By the end of

August. following the fall of Awabil to a mixed force of Shaibi

and Yafai irregulars, Zaidi forces had withdrawn from almost all

territory in and adjacent to Dhala. They had fought with

tenacity and resource, but could do little against the force

majeure of British air power.

Major Fowle (in his acting capacity as Resident) wrote to the

RAF Commander in Aden, Group-Captain Mitchell, on 15 July to

record his appreciation of Rickards’ services. Fowle noted

that ‘in addition to the Intelligence duties which he

performed for you, his W/T messages have been of great

assistance to me in keeping in touch with the political

situation, while his presence with the tribes, and his driving

power in getting them forward, have been very material factors

in their taking the town’. And in a letter to the Colonial

Secretary dated 8 September 1928, Sir Stewart Symes, the newly

arrived Resident, referred to the ‘remarkable daring and

discernment’ which Rickards had displayed during the Dhala

campaign, ‘ably helped’ by Hassan Muhammad. Rickards was

awarded the OBE, and among the few papers surviving from his

years in Aden are letters of congratulation from two leading

Adeni merchants: Karim Hasanali and F [Cowasjee] Dinshaw, both

of whom had interests on either side of the disputed border.

|

Right to left:

Aubrey Rickards, Aircraftman A Smith, Hassan Muhamma and

local tribesman, Dhala Fort, 1928.

Courtesy: James Offer |

The air defence of Aden, and the strategic need for an air

link between Aden and Iraq, created a requirement for a

multiplicity of landing grounds to serve the comparatively short

range aircraft of those days. It was a requirement which

Rickards, harnessing his professional skills to his innate love

of travel and exploration, was well equipped to fulfil. He had

constructed a landing ground in Dhala in July 1928, and during

the next few years, travelling by air and overland to different

parts of the Protectorate, he surveyed and constructed most of

the 35 landing grounds used, or required for future use, by the

RAF. An allied objective of his surveys was to fill in blank

spaces on the map. As George Rentz wrote in The Middle East

Journal in 1951, ‘he sketched maps of what he saw from the

cockpit and quietly made notable contributions to geography’.

One of several sketch maps which Rickards made during his time

in Aden appeared in The Geographical Journal of March

1931, as an appendix to Squadron-Leader R. A. Cochrane’s

account of an air reconnaissance of Hadhramaut which he and

Rickards had undertaken in November 1929. Cochrane’s paper was

illustrated with photographs, taken by Rickards, of the region’s

striking lunar landscape. The Dutch traveller, Van Der Meulen,

acknowledged the help — air photographs, sketches and other

data — which he and Von Wissman had received from Rickards

during their first visit to southern Arabia in 1931, and Von

Wissman drew on this material in preparing his own celebrated

map of the region.

Towards the end of 1929, Rickards travelled by dhow from

Mukalla along the Mahra coast to Dhofar, and he is believed to

have made a further voyage along the coast the following year,

this time from Aden, to deliver a cargo of aviation fuel to

Salalah. In an article on Soqotra published in The Field in

May 1937, he refers to a journey which he had made to that

island on board a Sun badan; he revealed neither the date

nor other details of the voyage, but the article illuminates his

interest in local history and ethnography. In 1932 he travelled

from the coast of Hadhramaut to the interior to construct a

landing ground at Shibam; his film of this journey was later

shown at the Royal Geographical Society (RGS) but has yet to be

traced. The new landing ground at Shibam enabled the Resident in

Aden, Sir Bernard Reilly, to make an historic first visit to

Wadi Hadhramaut in 1933. Freya Stark also had reason to be

grateful to Rickards, for it was from Shibam that the RAF flew

her to hospital in Aden, after she had fallen seriously ill

during her travels in 1935. These were the subject of her

lecture to the RGS in December that year, which Rickards

attended, joining Cochrane and others in congratulating her

during the discussion afterwards.

According to Philby, who visited the region in 1936, Rickards

also explored Wadi Duhr and Wadi ‘Irma, at the western end of

Wadi Hadhramaut, before proceeding south of Shabwa and westwards

to Nisab. Philby added that Rickards’ death in 1937 had left

‘a regrettable gap in the ranks of Arabian exploration: the

airman has but slender opportunities of constructive work in

Arabia, but he [Rickards] was certainly one who made the most of

such chances as came his way and fully earned a place on the

roll of those who have contributed to our knowledge of a still

little-known country’.

|

The

Amir of Dhala (centre, front row), HH Sultan Abdul Karim

Fadhl between him and the British Resident, Sir Stewart

Symes, Lahej, 1930.

Courtesy: James Offer |

In 1931 Rickards accompanied Lord Belhaven and Colonel M. C.

Lake on a Journey from Nisab to Beihan. This was Belhaven’s

first meeting ‘with a remarkable personality.., his knowledge

of the country and of its customs was encyclopaedic ...’

Belhaven reproduced several of Rickards’ photographic studies

of Beihani tribesmen in his Kingdom of Melehior (1949),

and in this and his later memoir, The Uneven Road (1955),

he has left us with a vivid portrait of a man he greatly

admired:

‘he was of medium height and capable of great physical

endurance. I shall not forget his reddish hair and bright blue

eyes, his sharp sense of humour, and the easy confident

carriage of his shoulders ... he had the trust of the Arabs to

a degree which I have not seen surpassed, despite his lack of

Arabic, which he spoke with a minute vocabulary and a

confusing disregard for grammar. It was hard to tell which,

between him and Lake, had a better knowledge of the country.

Rickards had method in finding and retaining information,

while Lake was unmethodical and reluctant to impart what he

had learned ... With Rickards all was shared. He never failed

to visit me on his return from his many expeditions, bringing

with him maps and photographs and all his official reports ...

When Rickards died in an air accident, what fire and light

perished!’

The poignant story of the death of Rickards and his two

companions, Pilot Officer McClatchey and Aircraftman O’Leary,

when their RAF Vincent crashed at Khor Gharim in October 1937;

of their makeshift burial beside that desolate creek on the

southern coast of Oman; of their reburial in Muscat some sixty

years later, has been told in detail by Cohn Richardson in his

book Masirah: Tales from a Desert Island (2001). The

accident occurred during Rickards’ second posting to Iraq

after leaving Aden, this time attached to RAF, Basra, but based

in Bahrain, with liaison duties covering the Gulf. Suffice it to

say here that Rickards’ two daughters, who had lost their

father in childhood, his nephew, niece and grandson were able to

attend the reburial service held at the Christian Cemetery,

Muscat, in May 1998.

When news of Rickards’ death reached Sultan Abdul Karim

Fadhl of Lahej, ruler of the most influential state in the

western half of the Protectorate, he wrote to the Governor of

Aden asking for his condolences to be conveyed to Rickards’

family. These were gratefully acknowledged by Rickards’ widow,

Anna, and his father, Robert. The Sultan’s regard for

Rickards, and regret at his passing, will have been shared by

many others in southern Arabia and beyond.

JOHN SHIPMAN

The Editor is grateful to Mr James Offer, nephew of the late

Wing Commander Rickards and trustee of his papers, for his

invaluable assistance, and for permitting publication of the

photographs.

|

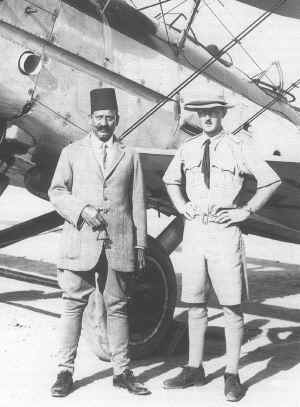

Rickards

with HH Sultan Umar bin Awadh al-Qu-aiti, ruler of the

Hadhrami State of Shihr and Mukalla, c 1930.

Courtesy: James Offer |

July 2002

|