Development and growth of the internet

The Arab countries lagged behind most of the world in adopting the internet. One factor, until the late 1990s, was the technical difficulty of using Arabic on the internet (and on computers more generally) which tended to restrict use to those who could work in English or, in some cases, French. Another factor was cost (including high connection charges, often through a government-controlled monopoly). Saudi Arabia and Iraq were the last Arab countries to provide public internet access, in 1999 and 2000 respectively.

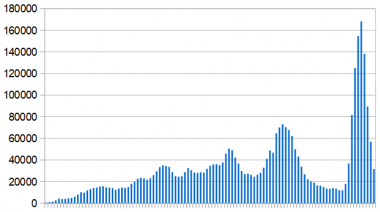

By the middle of 2008, more than 38 million Arabs were believed to be using the internet at least once a month and overall internet penetration (users as a percentage of population) had reached 11.1% [see table]. This was still only about half the world average (21.9%) but all the signs pointed towards continuing rapid growth. The largest numbers of users were in Egypt (8.6 million), Morocco (7.3 million) and Saudi Arabia (6.2 million). As might be expected, the highest penetration levels were found in some of the wealthy Gulf states: the UAE (49.8%), Qatar (37.8%), Bahrain (34.8%) and Kuwait (34.7%) – all well above the world average. Further down the list, Lebanon, Saudi Arabia and Morocco were near or slightly above the world average.

Having accepted the inevitability of the internet, the first instinct of Arab regimes was to look for ways to control it. This was based partly on their fears of political subversion but also on the fears of conservative and religious elements that it would undermine “traditional” values – fears that in both cases were well-founded. The favoured approach often reflected the broader mindset of the regimes concerned: the Saudis opted for an extravagant high-cost, high-tech solution, while Iraq under Saddam Hussein surrounded internet use with barely-penetrable bureaucracy.

The internet in Iraq under Saddam Hussein

In Iraq, UN sanctions made personal computers scarce and expensive, and modems – essential for connecting to the internet – were banned by the regime until 1999. Public access was eventually granted through the General Company of Internet and Information Services, a government monopoly. Outgoing and incoming emails were routed through the censorship department, which meant they could take several days to be delivered. Those who could afford an internet subscription (which at $750 a year was prohibitively expensive for most Iraqis) had to sign an application which said:

The subscription applicant must report any hostile website seen on the internet, even if it was seen by chance. The applicants must not copy or print any literature or photos that go against state policy or relate to the regime. Special inspectors teams must be allowed to search the applicant’s place of residence to examine any files saved on the applicant’s personal computer.

There were also sixty-five permitted web cafes (known in Iraq as “internet centres”) with unlimited powers to supervise usage:

Before a visitor could use the internet centre, they had to be interrogated by those running the centre about the web pages they intended to surf. When using a computer, visitors had to turn the monitor towards the centre’s door and were prohibited from deleting the history that records the web pages they accessed …

If visitors were actually allowed to use the internet after agreeing to these conditions, they typically found themselves presented with either Saddam Hussein’s picture (which was on the majority of the permitted web pages) or a large “X,” informing them that the web page was banned in Iraq. This was, of course, only if they were allowed to use the internet: those in charge of the centres could arbitrarily bar visitors from using a connection if they did not know the visitor or if they didn’t like the way the visitor looked. Authorities could decide that someone had no reason to use the internet and order them to return home.

This may have given the Iraqi regime some comfort, but it was scarcely watertight. Following the 1991 Gulf war, Saddam had lost control of the Kurdish provinces in northern Iraq, where internet access was unrestricted. Young Iraqis who wanted to use the internet without government monitoring simply travelled north, sometimes in groups. Around ten% of the customers in Kurdish web cafes were said to be visitors from the south.

The internet in Saudi Arabia

In Saudi Arabia, meanwhile, the council of ministers issued a set of internet rules which, among other things, prohibited users from publishing or accessing:

-

Anything contravening a fundamental principle or legislation, or infringing the sanctity of Islam and its benevolent shari’ah, or breaching public decency;

-

Anything contrary to the state or its system;

-

Reports or news damaging to the Saudi Arabian armed forces, without the approval of the competent authorities;

-

Anything damaging to the dignity of heads of states or heads of credited diplomatic missions in the kingdom, or that harms relations with those countries;

-

Any false information ascribed to state officials or those of private or public domestic institutions and bodies, liable to cause them or their offices harm, or damage their integrity;

-

The propagation of subversive ideas or the disruption of public order or disputes among citizens;

-

Any slanderous or libellous material against individuals.

It was unclear from this how users could ascertain that information was not false or damaging to Islam or the dignity of heads of state, etc, before viewing it. The rules also included various other prohibitions against advertising and commercial activity on the internet except with “the necessary licences”. Internet service providers (ISPs) were required to keep detailed records of users, including “purpose of use”, “the time spent, addresses accessed or to which or through which access was attempted, and the size and type of files copied”, and “provide the authorities with a copy thereof, if necessary”. Most importantly, though, ISPs were required to route all traffic through the Internet Services Unit (ISU) at King Abdulaziz City for Sciences and Technology in Riyadh.

The ISU houses the largest and most sophisticated internet-censoring system in the Middle East – based on technology that western companies eagerly competed to provide. In principle this is very similar to the filtering systems that parents and schools can purchase to prevent children accessing unsuitable websites, except that in accordance with Saudi Arabia’s paternalistic approach to government it is done on a national scale.

The ISU justifies blocking of pornography on religious grounds but makes no attempt to justify censorship of non-pornographic websites, which is done “upon direct requests from the security bodies within the government”. It says it has “no authority in the selection of such sites and its role is limited to carrying out the directions of these security bodies”.

The ISU’s system relies on frequently-updated lists of “undesirable” sites provided by SmartFilter, plus additions by the Saudis themselves. There is also some input from the public: users who try to access a blocked page can ask to have it unblocked (with the attendant risk of drawing the authorities’ attention to their activities). Users can also ask to have unblocked pages blocked. In 2001, the ISU was receiving more than 500 blocking requests from the public every day (about half of which were eventually acted upon) and more than 100 requests to have pages unblocked. By 2004, the number of blocking requests was reported to be running at 200 a day, with only a “trickle” of unblocking requests. This suggests that some sections of the Saudi public are considerably more enthusiastic about censorship than the ISU itself.

After testing 60,000 web addresses for blocking by the Saudi authorities over a three-year period, the OpenNet Initiative (ONI) reported:

We found that the Kingdom’s filtering focuses on a few types of content: pornography (98% of these sites tested blocked in our research), drugs (86%), gambling (93%), religious conversion, and sites with tools to circumvent filters (41%). In contrast, Saudi Arabia shows less interest in sites on gay and lesbian issues (11%), politics (3%), Israel (2%), religion (less than 1%), and alcohol (only 1 site).

Although only a few religious sites were blocked, ONI found that most of those blocked “involved either views opposed to Islam (especially Christian views) or non-Sunni Islamic sects (including Shi‘ism and Sufism)”. A “significant minority” of Baha’i sites were also blocked but the ONI found no blocking of sites related to Judaism, “and very few sites with Jewish or Hebrew content”. Some sites relating to the Holocaust were blocked, “though this occurs primarily because SmartFilter categorises many of these sites as having violent content”.11 Several sites supporting al-Qa’eda were found to be blocked as well as the sites of al-Manar (the Hizbullah TV station) and the Palestinian al-Quds brigades. In the religious area, the blocking of Shi‘i websites is perhaps most significant because it further marginalises the kingdom’s own Shi‘i minority (thought to be around five% of the population).

In the political area, ONI found blocking of “several sites opposing the current [Saudi] government along with a minority of sites discussing the state of Israel, or advocating violence against Israel and the west, and a small amount of material from Amnesty International and Amnesty USA”. In the media area, no major news outlets were blocked, though some e-zines were.

Although the Saudi filtering may not appear particularly aggressive except in terms of protecting internet users’ “morality”, it does result in unknown numbers of “innocent” pages being accidentally blocked. One early example was the blocking of information about breast cancer because of the objectionable word “breast”. A women’s human rights site was also classified as “nudity” because of one image of a naked woman showing torture marks.

“Internet filtering is inherently error-prone,” the ONI report said. “We found incorrectly categorised pages in every area we tested extensively.” This obviously causes inconvenience to users, even if they are not seeking to break the rules laid down by the authorities. A survey by the ISU itself in 1999 found that 45% of users thought the blocking was excessive (41% thought it reasonable and 14% thought it was too little). In another ISU survey, 16% cited blocking as a “common problem” when using the internet. More recently, the acting general manager of the King Abdulaziz City for Science and Technology told Arab News: “Of those who log on to the internet, 92.5% are trying to access a website that, for one reason or another, has been blocked.”

In due course, Saudi internet blocking will probably be remembered, along with the prohibitions on satellite dishes and camera phones, as just one in a long line of futile attempts to stop the clock for the sake of “traditional” values. However, it has possibly served one useful purpose by allowing the internet to take off in the kingdom without arousing undue ire from the most reactionary elements. It is worth recalling the furore over the introduction of television, which was eventually accomplished in 1965 after King Faisal promised that the principles of “Islamic modesty” would be strictly observed, and that the broadcasts would include a large proportion of religious programmes. With the internet, these problems were averted by ensuring that a filtering system was in place before the public were granted access. Reassuring the traditionalists may be one reason why the ISU is uncharacteristically open about its activities, frequently trumpeting its “success” in blocking pornography.

It is also worth pointing out that, even with the filtering, the internet has given Saudis access to far more information and ideas than they ever had before. The “old media”, such as print, are still subject to more stringent – if sometimes erratic – control. Journalist Molouk Ba-Isa described one everyday occurrence:

Last week, in the post, I received two catalogues from a US company, Lands’ End. The cover and all the pages through [to] page 42 of one catalogue had been torn off. The missing pages in the first copy of the Lands’ End catalogue contained some discreet photos of women in swimsuits. I know this because the second Lands’ End catalogue came through the post intact. Both catalogues were exactly the same. Even sillier, by simply clicking to the company’s website, I could see all the swimsuits.

At a time when we have a desperate need as a nation to allocate resources to education, infrastructure and health care, somewhere a group of Saudis is spending their days tearing pages out of magazines and catalogues to protect my morality – and getting paid for it. My psyche wasn’t permanently damaged by seeing the swimsuit photos in the second catalogue. I’ve seen worse just by visiting the swimming pool at almost any housing compound in al-Khobar.

Despite the efforts of the ISU, and despite the nuisance caused, internet filtering does not prevent Saudi users from accessing blocked pages if they seriously want to do so. According to IT journalist Robin Miller, writing in 2004, the head of the ISU conceded that filtering is “a way to protect children and other innocents from internet evils, and not much more than that”.17 One obvious, if expensive, way of circumventing the system is to use dial-up connections in neighbouring countries. Another method is to get some technical help. In 2001, Arab News reported that government blocking had created new business opportunities for those who know how to get round it. A reporter who presented himself as wanting access to blocked sites “had no trouble at all in finding willing hackers in every computer centre in Riyadh”, the paper said. “They also offered access to personal email accounts and sold pornographic DVDs.” Charges for providing access to blocked sites ranged from SR100 to SR250 ($27–$67).

The most popular method, for those with the expertise, is to connect to an open proxy server outside the kingdom. Although the government firewall sees the user connect to the server it does not see subsequent requests for blocked pages. Naturally the authorities are aware of this practice and they try to add proxy and anonymiser sites to their blocking lists, but ONI notes: “Finding and blocking open proxy servers is a labour-intensive task since these servers change domain names and IP addresses frequently to evade such filtering.” In 2004, ONI found that only 27% of the proxies and 41% of the anonymisers it tested were blocked. After trying this out for himself during a visit to the kingdom, Robin Miller concluded:

The Saudi Internet filters are easy to defeat. I found at least a dozen anonymous surfing sites that let me view all the porn anyone could want in less than thirty minutes, and I have viewed more online porn while testing the Saudi content filters than I had looked at in my entire life before this experiment.

Internet censorship in other Arab countries

Although Saudi Arabia’s internet censorship has attracted a lot of attention (and criticism), ONI found evidence of broad filtering in six other Arab countries: Oman, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, the UAE and Yemen. Four more – Bahrain, Jordan, Libya, and Morocco – were found to carry out “selective filtering of a smaller number of websites”. No evidence of blocking was found in Algeria, Egypt or Iraq.

However, technical advances, more diverse ways of accessing the internet, wikis, blogs, RSS feeds, dynamic web pages, plus growing use of multimedia – podcasts and videos as well as plain text – all make the censor’s task more difficult and probably, in the end, futile. Centralised filtering (often through a state monopoly on internet access) also creates technical vulnerability: “Sending all internet traffic in the whole country through a single chokepoint obviously creates a single point of failure,” Miller notes. Besides Riyadh, the Saudis have a second gateway in Jeddah, “but this is nowhere near the level of fail-safe connectivity major US online companies expect from their bandwidth providers”. Time is probably not on the side of the censors. Jonathan Zittrain and John Palfrey, two Harvard experts on internet law, explain:

Regardless of whether states are right or wrong to mandate filtering and surveillance, the slope of the freedom curve favours not the censor but the citizens who wish to evade the state’s control mechanisms. Most filtering regimes have been built on a presumption that the Internet is like the broadcast medium that predates it: each website is a “channel”, each web user a “viewer”. Channels with sensitive content are “turned off”, or otherwise blocked, by authorities who wish to control the information environment.

But the Internet is not a broadcast medium. As the Internet continues to grow in ways that are not like broadcast, filtering is becoming increasingly difficult to carry out effectively. The extent to which each person using the internet can at once be a consumer and a creator is particularly vexing to the broadcast-oriented censor … the changes in the online environment give an edge to the online publisher against the state’s censor in the medium-to-long run.

In the end, though, these technical difficulties may be outweighed by other considerations. The internet differs from the press and broadcasting in that government attempts to control it have far more impact on business activity; especially the modern, international, IT-based types of business. The problem of reconciling censorship with the need for unfettered business access is illustrated by the UAE, where one internet provider serving most of the country uses filtering extensively while the other, mainly serving the Dubai free zone, does not. How long these two conflicting approaches can survive side by side in the same country remains to be seen.

Source: What's Really Wrong with the Middle East, by Brian Whitaker (Saqi Books, 2009).

* Zittrain, Jonathan and Palfrey, John: ‘Internet Filtering: The Politics and Mechanisms of Control.’ In: Deibert Ronald, et al (eds): Access Denied: The Practice and Policy of Global Internet Filtering. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2008.

Further information

Internet case studies:

Tunisia, November 2005

Bahrain, February 2005

United Arab Emirates, February 2005

Saudi Arabia, 2004

Yemen, 2005

OpenNet Initiative: Middle East and North Africa

Helmi Noman and Elijah Zarwan. Includes country profiles relating to internet.

Mapping the Arabic blogosphere

A detailed study of the Arabic language blogosphere by the Internet and Democracy Project at Harvard University, June 2009.

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information

Egyptian-based campaigning organisation

The internet in the Arab world: a new space of repression?

by Gamal Eid, Arabic Network for Human Rights Information (2004). Includes sections on Bahrain, Egypt, Iraq, Jordan, Libya, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Tunisia, the UAE and Yemen.

Electronic media and human rights

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information

Steps on the road: mutual support between the internet and human rights

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information

Implacable adversaries: Arab governments and the internet

Arabic Network for Human Rights Information

False Freedom: Online Censorship in the Middle East and North Africa

Human Rights Watch, 2005

The Internet in the Middle East and North Africa: free expression and censorship

Human Rights Watch, 1999. A detailed survey of Internet use and Internet policy in the Arab world, though now somewhat dated.

The information revolution in the Middle East and North Africa

by Grey Burkhart and Susan Older. RAND Corporation, 2003

Saudi Arabia: rules for internet use

Council of Ministers Resolution, 12 February 2001

Companies compete to provide internet veil for the Saudis

by Jennifer Lee. New York Times, 19 November 2001.

CyberOrient

Online journal of the virtual Middle East

Meet Saudi Arabia’s most famous computer expert

by Robin Miller, Linux.com, 14 January 2004.

Most of kingdom’s internet users aim for the forbidden

by Radi Qusti. Arab News, 2 October 2005.

Everyone’s guide to by-passing internet censorship

The Citizen Lab, University of Toronto. September, 2007. Explains various techniques for accessing forbidden websites.

Hackers for hire

by Jameel al-Balawi. Arab News, 3 November 2001.

Internet Services Unit

The department of King Abdulaziz City for Science & Technology (KACST) responsible for providing (and blocking) internet services in Saudi Arabia.

Dictatorships get to grips with Web 2.0

Reporters Without Borders.

Virtually Islamic

Muslims on the internet (book review)

Saudis claim victory in war for control of web

Brian Whitaker. The Guardian, 11 May 2000