An e-book by Brian Whitaker exploring theunification of north and south Yemen in 1990, and its aftermath

7. The international dimension

Download chapter as Word document

YEMEN has long been the odd man out in the Arabian peninsula: poor, populous and republican in a region dominated by extraordinarily wealthy but scantily populated monarchies. Alone among the peninsular states, neither neither part of Yemen had profited directly from the oil boom of the 1960s and 1970s, and neither had joined the rich states’ club, the Gulf Co-operation Council (GCC). These factors, together with the Marxism of the south, meant that almost any changes emanating from Sana’a or Aden were liable to be regarded warily by Yemen’s neighbours. Thus in 1990, although the peninsular states formally welcomed unification (since they were obliged to pay lip-service to Arab unity), in reality they greeted it with a mixture of coolness and consternation. For some of them, the fact that Yemen espoused democratisation along with unification made the changes doubly disturbing.

Unification created a new state with a combined population of around 15 million citizens. Though population figures in the Arabian peninsula tend to be unreliable – they are often estimates and the estimates can vary widely – Yemenis greatly outnumbered Kuwaitis, Omanis, Qataris, Bahrainis and Emiratis. They also equalled or possibly outnumbered Saudi citizens. Population is a sensitive issue among the oil-producing Gulf states, since they depend heavily on foreign workers and despite enjoying enormous wealth lack the human resources to protect it – as was amply demonstrated in 1990 by the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. Yemen’s comparatively large population, further enlarged by unification and coupled with a high birth rate, may not have been of much practical consequence at the time but it was one of the psychological factors lurking in the background.

The political changes that accompanied unification were no less disconcerting psychologically. In a region where states are generally run along the autocratic lines of a 19th-century family business, multi-party democracy tended to be perceived as no less revolutionary than the old Marxist regime in south Yemen. Firstly, there were fears that democratisation in Yemen could create pressure for similar measures in Saudi Arabia and upset the stability of the monarchy. Secondly, there was the fear that Saudi opposition groups might look to Yemen for support, and that Sana’a, well aware of Saudi support for opposition groups in Yemen, might feel justified in providing it. There was thus a possibility that a vicious spiral would develop in which each country’s fears were constantly fuelled by the other’s response.

Unification also came at a time when Saddam Hussein of Iraq, after the war with Iran, was adopting an increasingly belligerent stance towards Kuwait and Saudi Arabia; having fought Iran in part as their proxy, he was now seeking recompense. Yemen itself had long-standing relations with Iraq: the original connections were religious, but the two countries also had economic, military and political ties. There was a strong element of Iraqi-orientated Ba’athism in north Yemeni politics, and at an international level the country had tended to align itself with Iraq rather the Gulf states. President Salih regularly used Iraqi military advisers and his Republican Guard was modelled on Saddam’s. Furthermore, Yemeni troops had fought alongside Iraqis in the war with Iran.

The formation of the Arab Co-operation Council in 1989, consisting of Iraq, Yemen, Egypt and Jordan, was seen by some as the birth of a new alliance which might one day challenge the GCC. There is also no doubt that Saddam supported and encouraged Yemeni unification – to the extent that some have claimed, in the light of the invasion of Kuwait a few months later, that he saw it as a building-block in his regional master-plan. Had the Arab Co-operation Council become a success and also developed into a military alliance, the Saudis would have had good reason to be alarmed. As it turned out, however, the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait (and the international response to it) forced Yemen’s relations with Saddam to be drastically scaled-down – but not without causing enormous damage in the meantime.

Relations with Saudi Arabia have always been a central feature of Yemeni foreign policy, not merely because the kingdom is the dominant state in the peninsula and Yemen’s most important neighbour, but also because the Saudis’ perception of their security needs is that they should seek to influence Yemen as much as possible in order to prevent it from becoming a threat. According to this view, Saudi interests are best served by keeping Yemen “on the wobble” (as one western diplomat put it) [1] – though not so wobbly that regional stability is jeopardised. Before unification, this amounted to ensuring that north and south Yemen focused their attentions on each other rather than on their non-Yemeni neighbours. For the strategy to succeed, it was essential to maintain an equilibrium between both parts, so that neither became dominant. Thus Soviet support for the south was generally matched by Saudi support for the north, coupled with frequent meddling in the internal affairs of both parts. To some extent, the north exploited this policy to its own financial advantage, but even so there were drawbacks. Most importantly, it created dependence on the Saudis. Apart from official aid and unofficial aid (in the form of bribes to various tribal leaders), remittances from Yemenis working in Saudi Arabia had become the mainstay of the northern economy.

Because of the relative poverty of Yemen, large numbers of Yemenis have traditionally sought employment abroad. During the oil boom of the 1970s, many found work in the rich monarchies of the Gulf, but especially in Saudi Arabia. Northern Yemenis were allowed to enter the kingdom on terms which were easier than those for nationals of other countries (including the PDRY). They had no need for a Saudi sponsor, and were allowed to own businesses without the customary Saudi partner. In Sana’a’s view these privileges were not merely a favour bestowed by the Saudis but had a legal basis: letters exchanged by the Saudi and Yemeni leaders in 1934 at the signing of the Treaty of Ta’if (which delineated part of the common border) could be interpreted as allowing relatively unrestricted Yemeni entry into the kingdom. Naturally, Sana’a made a point of interpreting them in this way and regarded them as an integral part of the treaty.

Together with dependants, the number of Yemenis living in Saudi Arabia probably approached two million at its peak [2]. Although in the short term their remittances brought tremendous benefits to north Yemen, the longer-term effects were more debatable. In the first place, the remittances tied north Yemen’s economy to Saudi Arabia – which meant it would suffer if political relations deteriorated. Meanwhile, the influx of cash into Yemen from expatriate workers caused inflation and huge disparities in wealth where the families who had no members working abroad were the first to suffer. Agriculture declined as able-bodied workers drifted away from the countryside, leaving villages populated largely by women and those males who were either too old or too young to work abroad. Gradually, the delicate system of mountain terraces began to fall into disrepair, leading to soil erosion and further agricultural decline [3]. Even at its best, the relationship between the Saudis and their Yemeni guest-workers was by no means harmonious: the Saudis, for their part, seem to have feared that Yemenis in the kingdom might foment opposition to the monarchy [4].Yemenis, in turn, also complained of ingratitude. It was their labour, they said, which had built Saudi Arabia – without adequate compensation. They had performed many of the jobs that Saudis were unwilling or too lazy to perform themselves. Many Yemenis complained of discrimination and harsh treatment in Saudi Arabia. Comparisons are sometimes drawn here with the British attitude towards Irish labourers. Halliday, for instance, quotes one elderly Yemeni living in Britain as saying: “The Irish are like the Yemenis. They built London, just as the Yemenis built Saudi Arabia. No wonder the Saudis and the English get on so well – they don’t do any work.” [5]

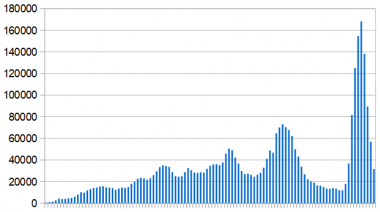

At the time of unification, however, north Yemen’s economic dependence on the Saudis was in decline. Both the value of remittances and the numbers of Yemenis in Saudi Arabia had been falling for some years, so that by 1990 remittances were less than 30% of their peak level. This was due to several factors: reduced levels of in construction work in Saudi Arabia, the replacement of Yemenis by Asian workers (on lower wages), and the fact that as migrant Yemeni workers became more settled in the kingdom they sent less money to relatives back home [6].

Although relations with Saudi Arabia loomed particularly large in north Yemen’s foreign policy, the same could not be said of Saudi Arabia’s relations with Yemen. The kingdom’s foreign policy was altogether wider and more complex. Regionally, the Saudi Arabia has six land neighbours besides Yemen (Jordan, Iraq, Kuwait, the Emirates, Bahrain and Oman) whereas post-unification Yemen has only two (Saudi Arabia and Oman). In the east, across the Gulf, the kingdom faces Iran, and in the west, Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and Eritrea. Beyond the peninsula and its surrounding area, Saudi Arabia’s special position as the land of the Prophet makes it foremost among the Islamic states spread across Africa and Asia. Wider still, its oil wealth provides it with considerable influence over the world’s economy as a whole. Nevertheless, relations with Yemen – both before and after unification – presented a particular difficulty for Saudi Arabia, mainly because of the long-running border dispute, but also because of political differences and the suspicion of Yemeni connections among Saudi opposition groups. Before 1990 there had been periods of tension and even conflict between the two neighbours (for example when Saudi Arabia supported the royalist side during north Yemen’s civil war in the 1960s).

Saudi Arabia’s wary – even hostile – attitude towards Yemeni unification, coupled with Yemeni anxieties about the kingdom’s reaction, exacerbated relations during the early 1990s. At about the same time, three additional factors came into play. One was the discovery in Yemen, starting from the mid-1980s, of modest but useful quantities of oil and natural gas; the second was renewed interest in the border question and the third was the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. In combination these brought a rapid worsening of relations.

1. Oil:

Yemeni oil had begun to come on stream shortly before unification; by 1989 the northern fields were producing 200,000 barrels a day [7] and proven reserves at the time were estimated at four billion barrels [8]. Although modest in comparison with its neighbours’ oil resources, this gave Yemen, for the first time in its history, an independent source of wealth. Economic independence in turn held out the prospect of greater political independence because it made remittances and aid from Saudi Arabia less important. Internally, oil provided a substantial new source of revenue for the central government and, since existing tax revenue was extremely low, this created an opportunity for Sana’a to increase its control over the whole country by using its funds to benefit the more wayward tribes, possibly making some of the shaykhs less susceptible to Saudi bribery [9]. It was generally assumed that most forms of opposition and political intrigue in Yemen were funded by the Saudis. There was no documentary evidence for this but the stories were so widespread as to suggest they contained a good deal of truth. At the start of the 1990s, the Islah party (rather than the YSP) was considered the main recipient of Saudi largesse. Apart from the more straightforward forms of subsidy, the Saudis appear to have made frequent use of bribes to achieve specific ends – though not always successfully. During the 1991 constitutional referendum, the men of Sa’ada in the far north were allegedly bribed to abstain from voting but defied the Saudis by sending their wives to vote instead [10]. Later, during the 1994 war, a northern shaykh told friends he had been bribed by the Saudis to support the southern cause. When asked why he had failed to keep his side of the bargain, he replied: “The Saudis gave me only a little money”.

Another important effect of oil was to increase pressure for a settlement of the largely undefined border with Saudi Arabia. The issue had been of little practical consequence until the mid-1980s when Yemen discovered its first oil close to the notional line. Shortly afterwards Saudi Arabia began to assert territorial claims in oil concession areas allocated by Yemen, apparently to discourage further exploration by foreign companies under Yemeni auspices [11]. In 1991 Saudi forces reportedly chased out a party of French geologists working in the Hadramaut region [12]. The following year, the Saudis sent warning letters to six oil companies operating in Yemen: British Petroleum, Atlantic Richfield, Hunt Oil, Phillips Petroleum, Elf Aquitaine and Petro-Canada all received the warnings, according to diplomats in Sana’a. Most of them appear to have ignored the threats, though BP halted drilling work on a well in the Antufash block in the Red Sea [13].

Although the disputed oil areas were hugely important to Yemen, the quantities involved were marginal in terms of the Saudis’ overall production. This suggested that Saudi Arabia was less interested in acquiring the oil for itself than in depriving Yemen of the benefit in order to limit its prospects for economic development and independence. Possibly the Saudis also feared that Yemen would use its oil wealth to acquire modern weapons, as had happened with Iraq. Although oil revenue was unlikely to be sufficient to allow Yemen to build up its armed forces in the way Saddam Hussein had done, it did mean that for the first time Yemen would have the hard currency to buy weapons on the open market, should it choose to do so. It is important, however, not to over-estimate the military threat that Yemen was able to pose. Its financial resources were modest and likely to remain so; northern and southern forces were not integrated into a single fighting unit; and the main functions of the armies were (a) to maintain internal control and (b) provide employment of sorts for large numbers of young men.

Nevertheless, the border question was of such crucial importance to Yemen’s future that it was reasonable to suppose Sana’a might be prepared to fight for it. There was also reason to suppose that in a border conflict Yemen would not necessarily be defeated, despite the Saudis’ superior weapons. The Yemenis were likely to be more highly motivated than the Saudis, and the Saudis would have had to maintain forces at the far edge of the Empty Quarter, whereas the Yemenis would have much shorter lines of communication. With the outbreak of war over Kuwait, Yemeni oil assumed even greater importance. Oil revenue became a vital replacement for the loss of remittances following the enforced return of Yemeni workers from Saudi Arabia; Yemen also began to consume its own oil rather than exporting it, because of the UN embargo on Iraqi oil [14]. This, of course, added to concern over the border issue.

2. The border:

Yemen and Saudi Arabia shared one of the longest undefined borders in the world. Only a small part of the line had ever been agreed: a portion at the extreme north-western end stretching from a point just north of Midi on the Red Sea coast to Najran oasis. That was in 1934 under the Treaty of Ta’if, when, after a brief war, two ethnically Yemeni provinces, Asir and Najran, were ceded to the Saudis. The remaining eastern portion of the frontier – totally undefined – ran for almost 1,000 miles through mountains and desert, mostly unpopulated, on the fringes of the Empty Quarter. To the west, the maritime border in the Red Sea was also undefined, further hampering oil exploration.

Apart from the need for a settlement created by oil discoveries, there were a number of reasons why the border question came to the fore shortly after unification. From the Yemeni standpoint, unification made the mechanics of border talks more straightforward than previously because there would be only one Yemeni government negotiating with the Saudis instead of two. Meanwhile in 1992 the settlement of Yemen’s only other land border – with Oman – again tended to focus attention on the outstanding question of the Saudi border. Finally, the partial settlement of the border under the Treaty of Ta’if was due to lapse in 1992 [15]. Thus, by 1990 both parties were beginning to stake out their bargaining positions as a prelude to talks about renewal.

There were frequent Yemeni claims of Saudi troop movements in the frontier area. These usually coincided with periods of tension or new diplomatic moves on the border question [16] In October 1990, Saudi Arabia announced plans to construct a multi-billion dollar “military city” near Jizan at the north-western end of the border. This was to be one of a series in strategic areas, designed to house 50,000 officers and men with their families, and was described by Saudi officials as “a fortified bastion at our gates” [17]. In 1991 a Yemeni border post at Baq’ah in north-west Yemen was reported to have been captured by Saudi troops, though Riyadh denied this [18]. A bizarre diplomatic incident occurred in May 1992 when a Saudi weather forecast appeared to claim that the Kharakhayr region of Hadramaut belonged to the kingdom. As this was the birthplace of Vice-President al-Baid, it resulted in a stiff protest note from Sana’a [19]. Further complicating the issue, about the same time, the Saudis were reported to be offering Saudi citizenship to some traditionally Yemeni border tribes in Shabwa, Hadramaut and al-Mahara provinces [20].

On the Yemeni side, the new unified constitution signalled a tough, uncompromising position when it stated in the opening sentence: “The Republic of Yemen is an independent sovereign state, an inviolable unit, no part of which may be relinquished.” The last phrase was an insertion which had not appeared in the previous YAR constitution. The Yemeni government also did little to discourage speculation that it hoped to recover the “lost provinces” ceded in 1934, though there is nothing to suggest that such rumblings were anything more than a negotiating ploy. Yemen’s declared aim was to extend the issue beyond the small area covered by the Ta’if treaty and to seek a comprehensive border settlement – which now appeared feasible for the first time as a result of unification.

Despite all the posturing, the border dispute was more than a mere quarrel between two neighbours; it was a genuinely difficult question involving complex and highly technical issues. Both sides had wildly divergent views as to where the border should lie – at some points on the basis of quite slender and conflicting evidence. One of the difficulties in resolving this was the number of different claims made over the years by both regimes or their predecessors. The other was agreeing on what criteria should be applied: the principle of self-determination was not applicable in unpopulated areas, and in most parts neither side had a history of local administration which might reinforce a claim. The respective claims were based on a number of lines on old maps: the Violet Line, the Hamza Line, the Riyadh Line, the Philby Line, etc., representing earlier claims which had been rejected by one side or the other. These lines not only diverged by up to 200 km in places, but also crossed, creating at one point a small triangle in the middle which appeared not to be claimed by either side.

A further, but related, issue was that the Saudis had long sought a land corridor southwards to the Arabian Sea (and thence to the Indian Ocean). Strategically, their oil exports were potentially vulnerable to a military blockade because tankers from Saudi ports had to pass through one of three narrow waterways, none of which the Saudis controlled directly: the Strait of Hormuz in the Gulf, and the Suez Canal and the Bab al-Mandab at each end of the Red Sea. A pipeline to the open sea in the south would thus provide extra security. This was not strictly part of the border dispute (since the corridor was a Saudi desire rather than a claim) though in practice the two issues tended to be linked.

Shortly before the south achieved independence in 1967 there had been strong suspicions, particularly within the National Liberation Front, that Britain and Saudi Arabia were plotting an east-west partition in the south, or possibly even to hand the eastern provinces of Hadramawt and al-Mahra to the Saudis. The idea originally seems to have been to reduce instability in the region caused by Britain’s withdrawal from the Aden naval base, though it would also have improved the kingdom’s strategic position. After southern independence, Saudi-sponsored subversion in the south appears to have been aimed at separating the eastern provinces from Aden and the west [21]. Although these suspicions were not confirmed, they arose out of a meeting between King Faisal and Harold Wilson, the British prime minster, early in 1967. They were further fuelled by the fact that Britain handed the traditionally Yemeni Kuria Muria islands to Oman shortly before southern independence.

Subsequently, the Saudis proposed the corridor idea to both Oman and the PDRY – and both refused. In principle Yemen had no objection to a pipeline; the sticking point was that the Saudis, presumably for security reasons, had insisted on having full sovereignty over a strip of land on either side of it [22]. For a time, one possibility was to locate the corridor between Yemen and Oman, but that option was closed in 1992 following agreement on the hitherto undefined border with Oman. It is conceivable that the corridor plan was one factor behind the Saudis’ encouragement of southern separatism in 1994. If the secession had succeeded, granting a corridor would have been the most obvious way to repay the Saudis for their support.

The poor state of Yemeni-Saudi relations resulting from the Gulf war made talks on the border issue impossible during 1990 and 1991. They started, after a decent interval, with a ministerial meeting in Geneva in July 1992 and continued spasmodically and somewhat half-heartedly, for almost two years. They were broken off on April 26, 1994, just as the political crisis in Yemen was turning to war. It was not until 2000 that the issue was finally settled by the Treaty of Jeddah.

3. The invasion of Kuwait:

Less than three months after unification, Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait presented Yemen with a stark dilemma. It had long-standing links with Iraq; at the same time, it depended on remittances from Yemeni workers in Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states. Whatever Yemen decided to do, it was bound to suffer. Opting for what it saw as a middle course, Yemen simultaneously condemned the invasion of Kuwait and opposed Western military intervention, arguing instead for a regional – Arab – solution. In this it differed little from several other “neutral’’ Arab states, but as the only Arab member of the UN Security Council at the time, Yemen possibly felt it had a special responsibility on behalf of the Arab world. In any event, it was in a uniquely exposed position and its behaviour came under special scrutiny.

In the first Security Council vote imposing trade sanctions against Iraq, which was carried on August 6 by 13 votes to nil, Yemen abstained along with Cuba. In a second vote on August 25, allowing military enforcement of the blockade, the voting pattern was the same. Later, Yemen voted against the use of force to recapture Kuwait and its stance was interpreted in the West as evidence of secret support for Saddam, and by Saudi Arabia as nothing less than betrayal. Although Yemen declared that it would observe sanctions (but would not “impede international navigation” by challenging ships suspected of breaking them), Western diplomats questioned its sincerity [23]. A few days before the Security Council’s second vote, an Iraqi tanker, Ain Zalah, had begun to unload crude oil at the Aden refinery, though work apparently halted as soon as Yemen announced its decision to abide by sanctions. Two other Iraqi tankers, al-Fao and al-Qadissiyah, arrived empty in Aden after being refused entry to a Saudi port. A fourth, Baba Gurgur, took refuge in Aden after earlier failing to stop when US Navy frigates fired warning shots across its bows. Unnamed diplomatic sources cited by Associated Press also claimed that Iraq had flown 12 captured Kuwaiti fighter aircraft to Sana’a and that 36 Iraqi warplanes had been stationed in Ta’izz. Yemeni government ministers emphatically denied that there were any Iraqi warplanes or Iraqi forces in the country. About the same time, the British Consul-General in Aden, Douglas Gordon, was briefly arrested and then expelled from Yemen for taking photographs in the port area.

The outcome was that Yemen got the worst of all worlds, suffering more from the war than any other non-combatant country: UN sanctions cut off its trade with Iraq and the US cut off its aid (declaring Yemen’s vote “the most expensive no in history”). Saudi Arabia ended all economic assistance to Yemen and deployed troops in the frontier zone [24]. In addition, it announced that Yemenis working in the kingdom must find a Saudi sponsor or business partner or leave the country [25]. Almost none of them found sponsors or partners before the deadline, and within a few weeks some 750,000 people were bundled over the border into Yemen, many of them leaving behind most of their possessions [26]. Those who owned property in Saudi Arabia were obliged to dispose of it quickly, which in most cases seems to have meant selling it for a fraction of its real worth. Needless to say, the withdrawal of privileges for Yemenis was interpreted in Sana’a as a breach of the Ta’if treaty.

This amounted to double punishment of Yemen, for not only did the country suffer a sudden loss of remittances but also faced the problem of absorbing this huge influx of returnees. In the space of three months, Yemen experienced a 7% increase in its population and a 15% increase in its workforce, severely exacerbating unemployment. To begin to comprehend the upheaval this caused, in proportional terms one would have to imagine close to four million British expatriates suddenly arriving at Dover – jobless and largely homeless.

The luckier returnees drifted back to their cities and villages. In Sana’a, a year later, they could be seen every morning, sitting by the kerbside at major cross-roads, hoping someone would hire them for a day’s work. Most were still there by nightfall [27]. For months, several hundred thousand camped out on the hot and humid Tihama plain. The Yemeni government, arguing that they should not be treated as refugees in their own country, provided little comfort – hoping that this would encourage them to disperse. It worked up to a point. The numbers dwindled gradually, aided by outbreaks of cholera which at one point were killing 50-60 children every week.

Two years later, however, there were still about 100,000 returnees living on the outskirts of Hodeida on 1,400 acres of what had previously been waste land. By then, the encampments were acquiring an air of permanence, as well as bitterly ironic place names such as Saddam Street, Martyrs District and the Mother of Battles District. Amid the shelters built of sacking and rubbish, a handful of huts served as shops and there was even one two-storey plywood house, with an outside staircase and a sagging upper floor. A man who scraped together the cash to buy an old vehicle had started a bus service. These were the least fortunate of the returnees. Those with savings, skills or close family ties had moved on. Those who remained were unskilled, in some cases unemployable – and had virtually nothing. They told of belongings left behind, of televisions and video recorders sold to Saudis for a tenth of their value, of refrigerators abandoned along the road. Many of the men said they had been labourers or porters in Saudi Arabia, reflecting sadly that nobody in Yemen pays to have bags carried. Some had found casual jobs in Hodeida. Others lived by collecting leftovers from the back doors of restaurants. Officially, the Yemeni government provided everyone with bread, though its distribution was later taken over by Islah, for not entirely charitable reasons, since it regarded the camps as suitable breeding grounds for political agitation.

By no means all of these people had close connections with Yemen. Some had never previously lived in Yemen; one woman claimed to be a Saudi citizen married to a Yemeni; others, of distinctly un-Yemeni appearance, were probably of east African origin. There was little doubt that the Saudis had taken this opportunity to expel not only Yemenis but anyone else who had no passport and seemed to be a burden on the state: the blind, the infirm, beggars, plus a few thieves and drug addicts [28].

The result of the expulsions was a hardening of attitudes on both sides. In Saudi eyes, their actions were justified retribution for Yemeni ingratitude after decades of economic assistance at a level that no other state had come close to providing [29]. If the Saudis hoped the expelled Yemenis would blame the Sana’a government for their plight, they were mistaken. On the streets, in the buses and cafes, there was vigorous support for Yemen’s Gulf stance, coupled with undisguised admiration for Saddam Hussein. Of course the invasion of Kuwait was wrong, they said, but the what the Americans did was wrong, too. Saddam was a hero – he stood up to them. He didn’t win in the end, but nor was he truly defeated. There was no way he could win – the Americans fought with technology, not with their hands like men. Such conversations could be heard all over Yemen. Interestingly, most of the bitterness was not directed against the Americans (perhaps because they behaved so predictably) but against the Saudi royal family. Effete, luxury-loving princes who spent their time in European night-clubs, and proved incapable of defending their own country without American help, figured strongly in popular gossip [30]. Another complaint sometimes heard in Yemen, as in other parts of the Arab world, was that the Saudis’ vast oil wealth belonged by rights to the Arab nation as a whole. By this argument, the Saudi regime and the rest of the Gulf monarchies, were Western puppets, kept in power to ensure that the Arab nation remained weak and divided.

However, the deterioration in Yemeni-Saudi relations – despite the human suffering caused by the mass expulsions – was not entirely negative. Although many returnees had to leave their belongings behind, others brought large amounts of cash and equipment into the country. According to one estimate, this was equivalent to three years’ remittances in the space of a single year; it brought a rapid expansion of construction in Hadramaut and a modest revival of agriculture, most notably in Dhamar province [31]. And even if Saudi aid had not been abruptly cut off because of the war it would probably have declined anyway, since its original purpose – to bolster the north in its Cold War confrontation with the south – had now gone. As with oil discoveries, the expulsions reinforced Yemen’s political independence vis à vis Saudi Arabia. One Yemeni economist observed in 1992, “The Saudis did us a favour when they sent our workers home. They liberated us, but they haven’t realised it yet.” Liberation or not, the resulting hardship brought a timely revival of Yemen’s national spirit and obliged the northern and southern leaderships to focus for a while on more urgent matters than the differences between them. In the view of one northern politician, this added about a year’s grace before the final rupture between the GPC and YSP.

© Copyright Brian Whitaker 2009