Youssef Rakha: genius in a land of madness

Egypt's ground-breaking novelist

The Book of the Sultan's Seal, in its English translation, measures 203mm x 134mm, weighs approximately 410 grammes and has a brownish cover. It consists of 374 pages divided into nine sections which are dotted with little drawings by its Egyptian author, Youssef Rakha. That much can be said with confidence but attempting to describe it further is quite a delicate task. Not only is the book full of eccentricities; it has been hailed by some as the most significant Arabic novel in years.

In the words of the Palestinian writer/poet/translator Anton Shammas, Rakha has fulfilled "at long last, one of the dreams of modern Arabic novelists since the mid-nineteenth century: to formulate a seamless style of modern narration that places the novel in the world". In Shammas's view, The Book of the Sultan's Seal deserves an immediate place in modern Arabic literature's hall of fame.

The adjectives that others have applied to it include "stunning", "extraordinary", "brilliant", "unparalleled", "groundbreaking", "adventurous", "innovative" and – yes – "rambling" and "chaotic".

Even before you turn the first page of the prologue it's clear that this is going to be no ordinary read: "The Book of the Sultan's Seal," it says, "does not merely welcome solecisms and bad language but actually celebrates them." The great ninth-century Arabic writer al-Jahiz (“The Goggle-Eyed”, who allegedly died when a pile of books toppled onto him) is invoked in support of this iconoclastic approach.

In telling his story, Rakha adopts a pre-modern literary form – the epistle – and this, coupled with constant reminders of his cultural heritage gives the book a curious feel of being simultaneously very old and very new. The most original part of this old-new fusion, and the most dismaying for purists, lies in his use of language which swings deliberately and sometimes disconcertingly between high classical Arabic and the lowest kinds of vernacular. Rakha developed this specially for the purpose, and he calls it "Middle Arabic".

There are many who would shy away from trying to render such a book into English and, not surprisingly, the man who accepted the challenge – Paul Starkey, an emeritus professor at Durham University – was rewarded last week with the Saif Ghobash Banipal Prize for Arabic Literary Translation.

But what is The Book of the Sultan's Seal actually about? Starkey, in a Translator’s Afterword, writes that it can be read on several levels – “as an exploration of the Ottoman contribution to the make-up of the contemporary Middle East; as a study of the contemporary Arab Muslim's desperation for a sense of identity (heavily dependent, like all identities, on history); or simply as a rollicking good tale – by turns, suspenseful, riotous, and erotic.”

Others have viewed it as a dystopian picture of the author's home city – Cairo – and the society that inhabits it.

As for the tale itself, Rakha summarises it in the opening paragraph as "a day-to-day account of the events in the life of the journalist Mustafa Nayif Çorbacı from March 30 to April 19, 2007, as he himself recorded them in the weeks following this date, addressing this account, in the manner of classical Arabic books, to his friend, the psychiatrist Rashid Jalal Siyouti, who has been living in the British capital since 2001".

Re-summarised in the book's closing paragraph, it becomes "the story of Mustafa Çorbacı and his sudden transformation during twenty-one days from a Europeanised intellectual to a semi-madman who believed he could perform magic deeds to resurrect the Islamic caliphate".

Youssef Rakha was in London last week for the translator's award ceremony and a subsequent panel discussion. When I met him at a cafe in Covent Garden the following morning he was feeling the after-effects of the previous night's celebrations and, as sobriety returned, regretting having spent £11 (more than $15) on a packet of British cigarettes – money that would have bought six packets in Egypt.

For someone who might be on the verge of turning into a literary giant, Rakha struck me as remarkably modest and unassuming. That could have been due to his hangover, but he is also the product of one of Britain's more modest and unassuming universities – Hull. He graduated there in 1998 with first-class honours in English and philosophy, collecting the Larkin Prize for English and the Chris Ayers Prize for Philosophy along the way. Perhaps it was in Hull, too, that he acquired what seems to be a very British kind of diffidence: when asked to explain the critical hyperbole surrounding his work he says he thinks that “perhaps” it has “some kind” of originality.

I was curious to know how, with his Egyptian upbringing, he had found himself studying in Hull and what effect it had on him. Hull (or Kingston upon Hull if you want to be pretentious about it) is a city in north-east England – a proudly proletarian kind of place where, as Rakha recalled, if you drink wine rather than beer people think you are strange.

During the second world war, Hull was more badly damaged than any other British city – partly because its location on the Humber estuary made it easy for Luftwaffe bombers to find in the dark. What Hitler failed to destroy in the war, industrial decline wiped out later.

For a young Egyptian seeking to study abroad, all this gave Hull one great advantage: it was affordable. Rakha explained:

I'm an only child, so my parents could afford to send me to an English school [in Cairo] and I did GCSEs and A-levels and things. But then I went to Cairo University for a semester and I couldn't cope with it because it was so different – it was rote learning, they treated you as if you were in a prep school or something. So I gave this little speech to my parents, saying I had to go to university elsewhere, and they said "Well, if you do that you won't have any money when you get back."

I said "That's fine". I had been accepted in Bristol and in London but Hull seemed more affordable. I didn't know anything about Hull, so I went with that. It was OK. The university was just what I wanted but obviously the setting wasn't ideal.

Do you think Hull had some effect on you? It must have done.

I was profoundly disillusioned, because I had had these very grand ideas about the west, and how intelligent and cultured and civilised everything was. And then I ended up in Hull, but I think in a good way. To break that kind of adoration for the west so early in life was an important thing – you could see things more in perspective.

For a lot of Arabs, for a lot of Egyptians, this idea that somehow there is a better place, a place that is infinitely more advanced, more exciting, more whatever, never goes away. But when you end up living in Hull at 17 it goes away very fast.

What struck you about Hull when you arrived?

Well, it seemed dispossessed ... I mean the city; the university was different. The university was just middle class people. The city itself was extremely – what's the word – gutted. I remember seeing people who were dreaming of going to the United States – working class people.

Very much like Arabs dreaming of going abroad.

At the time it wasn't a very pleasant place. There was a chemical smell about the place. It was very spread out and derelict. Going for a kebab at eleven at night and walking down this street, completely deserted and it's cold and whatever and you are thinking "What am I doing here? How do I fit into this?"

The Book of the Sultan's Seal was Rakha's first novel. The Arabic edition, Kitab al-Tughra, appeared early in 2011 when Egypt was in the midst of revolution – which is why it didn't attract much attention at the time.

His second novel, Al-Tamasikh (“The Crocodiles”), which has also been translated into English, weaves the tumultuous events of 2011 with the story of a secret society of poets. Rakha, being diffident again, hastens to point out that linguistically The Crocodiles is “far less adventurous” than The Book of the Sultan’s Seal. Be that as it may, it’s still highly unusual: a prose poem consisting of numbered paragraphs.

Simon Assaf writes:

The book ignores any rules about time and space. One section dealing with an event in 1999 is suddenly interrupted by the choking gasses of Tahrir, or descriptions of wild parties where young urbanites blend love of Arab culture, American beat poetry, drugs, sex, violent arguments, “Satanic” heavy metal music and clumsy intellectualism. The Crocodiles breaks all the norms of the novel; it has no conventional structure, it jumps and cuts, breaks off from one narrative only to pick up the thread later.

Its description of sex … is shockingly frank, descriptive and at times uncomfortable. The poetry of the group is sometimes base and usually involves the constant reinterpretation of the same poem.

The short descriptions of Tahrir and the battles that follow are some of the most lucid to have been written.

There’s an extract from The Crocodiles here in English, and another here in Arabic. Comments on the Goodreads website range from “Rich and challenging” to “It gave me a headache”.

Rakha is now working on a third novel, this time in English:

I've only just started. It's still changing and I haven’t settled on anything. There are two kinds of pivots for it. One is the history of modern Egypt, starting in 1956, basically, with the nationalisation of the Suez Canal and all that, and ending with the death of Shaimaa al-Sabbagh [the female activist shot by Egyptian police during a demonstration last year].

Initially I was thinking in terms of somebody very like my mother, and so it might also be from the viewpoint of a very ordinary kind of lowest-common-denominator Egyptian woman who was maybe 18 in 1956 and then also dies around the same time [as Shaima].

I'm afraid to say anything because it still might change but I think I have arrived at a style that can work.

His switch to English highlights one of the main problems that Arab novelists face: a lack of readers:

It's part of the reason I want to try doing it in English, so that maybe there is more of a readership. It's the most frustrating thing. Not so much the sales … but just the fact that you don't feel there are enough readers for this kind of thing.

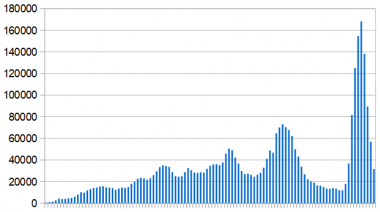

The last time I spoke to a publisher who is in the know, he said that 1,000 copies over a year is considered good, and that 5,000-10,000 copies becomes a best seller. Nothing sells more than 10,000 copies.

He’s talking here specifically about Arabic novels. Other types of book can sell more if – Rakha laughs – they are “bad enough”.

Mustafa Bakri [an Egyptian journalist and MP] writes these supposedly insider accounts – he wrote this book where the Mubarak sons were having a fight in front of the old man at the palace. He couldn't have been there and there's no reason to think that any of this happened. But he survives on that kind of thing, and the publisher said he sells up to 200,000 copies. Which, compared to the 10,000 of an absolute best-selling novel is remarkable.

This is why Rakha continues to subsidise his novel-writing with a job at al-Ahram Weekly and why, by default rather than design, he finds himself writing mainly for the intellectual elite:

It's not intentional I ended up writing for that segment of society. I feel my books should be read more widely – I don't understand why a book like The Crocodiles, for example, given the timing and the fact of the Arab Spring and everything else, wouldn't sell more all over the Arab world or wouldn't be read more widely. I don't think it's obscurantist or difficult at that level, I think it's quite approachable.

But is he, perhaps unconsciously, pandering to this elite audience? Rakha insists that he is not. Referring to The Book of the Sultan’s Seal, he says:

I suppose it's partly a learning experience. I realise now in a way that I didn't when I was wrote it, that maybe it is a difficult book. For example, a completely uncultured, not particularly literate friend of mine read the manuscript and loved it. [They] didn't have any problems whatsoever and they didn't think it was intellectual or anything, so I was hoping more people would interact with it this way.

Nevertheless, his books are replete with all sorts of allusions that will probably escape the average reader. Seth Messinger writes:

Rakha is impossibly erudite about Egyptian, Arab, European, and American literature. References to Egyptian authors proliferate throughout The Crocodiles as a way to index transitions from the generation of the 70s through to the burgeoning one of the Revolution. But, beyond this, poets from medieval North Africa, from Moorish and contemporary Spain, and from the United States are quoted or cited by characters as influences on their own ‘secret poetry’. In The Book of the Sultan’s Seal, Rakha uses his knowledge of antiquarian texts to invoke a cosmopolitan Muslim world spanning the shores of the Mediterranean into Asia, and deeper into Europe.

To help readers along, The Book of the Sultan’s Seal had three appendices in its Arabic edition – condensed in the English translation to a 16-page glossary of names and places. Recognising and understanding the allusions will obviously enrich a reader’s experience, but for those who don’t there are still plenty of things to appreciate. In his Translator’s Afterword, Paul Starkey acknowledges that some parts may “prove a little too allusive for some readers”, adding that “if anyone finds these passages too difficult or obscure, I suggest they may safely be skipped”.

On the other hand, once you start looking for allusions you may well find some that Rakha never intended. The idea of using magic to resurrect the Caliphate, for instance, might seem like a topical reference to the Islamic State – though the story was written long before the emergence of ISIS.

Similarly, in the English translation of The Book of the Sultan’s Seal, the name of the protagonist – Çorbacı – is spelled throughout in the Turkish alphabet. This, you might assume, is deeply significant. Not so, says the translator:

The reason for this has nothing to do with any scholarly or academic argument, but simply that following the publication of Rakha’s novel the character began to acquire a life of his own as Çorbacı in discussion on English-language websites, and it was thought too confusing to change it.

But perhaps, amid the craziness of Sisi’s Egypt, where a toddler can be mistakenly sentenced to life imprisonment for rioting and murder, there are some advantages in writing for a small, select audience. In a blog post last year, Rakha observed:

While creative writers in Egypt are by and large left to their own devices, this is only because their work is seldom scrutinised outside literary circles.

As a writer in Egypt you can only be torn between frustration over your work remaining obscure and concern with the trouble “success” could bring to your life.

Take the case of Ahmed Naji who, like Rakha, has written about sex and drugs in a dystopian Cairo and is now serving a two-year jail sentence for "violating public decency". Naji’s book, Istikhdam al-Hayat ("Using Life") had been printed in Lebanon and approved for sale in Egypt by the Egyptian censors. It caused him no problems so long as those who might be offended were unaware of it. But when an extract appeared in a newspaper, a man who claimed to have suffered heart palpitations from reading it reported Naji to the prosecutors.

Unlike many Arab writers, Rakha is not especially concerned with politics. Interviewed in 2015, he told Reuters:

If the Arab Spring proved anything it is that the problem is not just despotism. The problem is much bigger than that and whatever political problems and problems of governance you have are actually reflections of wider problems in society rather than the cause of the deficiencies in society.

Like thousands of others, he did his bit in Tahrir Square during the revolt against Mubarak but has been criticised over an article he wrote for the New York Times in 2013 celebrating the overthrow of President Morsi and the Muslim Brotherhood – and which by implication seemed to be supporting the seizure of power by Sisi and the military.

But politics is not Rakha’s forte. “In a sense,” he told me, “I'm trying to escape from politics”.

There is this quote from Joyce in Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man which says something like "history is a nightmare from which I am trying to awake". I think that applies to everything I have written in terms of fiction. So you are trying to go to a place that transcends history – which of course is impossible – but by going through history you are trying to get away from it. I think that's quite important.

Somebody said that your Cairo is like Joyce's Dublin.

Yes, I was very flattered by that. Dubliners is my favourite Joyce book as well.

But is there a kind of commentary on modern life in this?

I think a lot of it has to do with being between two cultures, not necessarily in the individual subjective sense but in the sense that if you live in a place like Cairo inevitably you are going to be answerable to contemporary norms which are very different from the cultural legacy. I think it's that kind of conflict – grey area – that stimulates me.

But also, I think, just what Cairo is like, how it forms people, how the experience of living there, growing up there, forms people, and the huge challenge of staying or becoming independently minded and contemporary – especially since the 1970s – which isn't as easy as it looks. I mean, it's much easier to dissolve into madness.

There's a certain madness in Cairo.

"Absolutely, yes."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed