A month after the US State Department published its annual country-by-country report on human rights, the Moroccan government has suddenly erupted in fury over the section about Morocco.

On Tuesday, the interior ministry denounced the report as a list of "inventions" and "lies" and accused the US of relying on information from "a few individuals with no credibility or a handful of Moroccans known for years for their aversion to the regime".

Among its numerous criticisms of Morocco's human rights performance, the American report said "systematic and pervasive corruption undermined law enforcement and the effectiveness of the judicial system", adding that "impunity was pervasive".

The row seems to have delighted the Russian propaganda channel, RT, which yesterday pointed out that the "human rights chief" in Russia's foreign ministry had already condemned the American report as a collection of "ideology-driven clichés and biased assessments" presented in "an unacceptable, didactic manner".

One of the strange things about the Moroccan reaction is that the State Department's latest report, covering the year 2015, doesn't really say much that is new. The reports are not written from scratch each year; they are basically cut-and-paste jobs, with whole paragraphs copied word-for-word from previous years plus a few insertions and deletions to take account of recent developments.

Thus, for example, the latest report says of Morocco: "The most significant continuing human rights problems were the lack of citizens’ ability to change the constitutional provisions establishing the country's monarchical form of government, corruption, and widespread disregard for the rule of law by security forces." The 2014 report said exactly the same, as did the 2013 report – though neither of those reports caused as much fuss from Rabat.

Another odd thing is that while the Russians complained about the American report like clockwork, as soon as it was published, it has taken the Moroccans a month to do so. Does this mean they have only just got around to reading it, or has something else happened in the meantime that might explain their sudden outburst of anger?

We can safely assume it was not the speech given by secretary of state John Kerry on April 18 – just a few days after his department's report was published – when he described Morocco as a "fascinating" country whose history intertwines with "key moments in the US history".

A more likely explanation lies in the long-running dispute between the US and Morocco over the future of Western Sahara which re-ignited towards the end of last month.

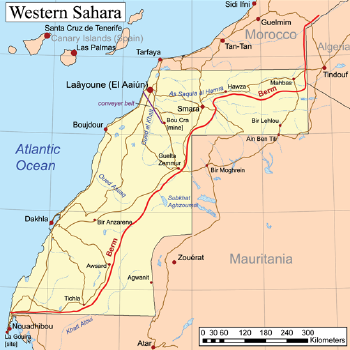

In 1975 a vast number of Moroccan civilians, escorted by around 20,000 troops, entered Western Sahara (or Spanish Sahara as it was called at the time) – an event celebrated in Morocco as "The Green March". This led to Morocco taking over the whole territory and triggered a 16-year war with the Polisario Front.

The war ended in 1991 with an agreement to hold a referendum in which the people of Western Sahara would choose either independence or formal integration with Morocco. A UN peacekeeping mission, Minurso, was established to monitor the ceasefire and organise the referendum. However, 25 years later, the referendum still hasn't happened.

Ban Ki-moon uses the O-word

In March, during a visit to Western Sahara, UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon described Moroccan control over the territory as an "occupation" – a term which the UN had previously avoided using. This angered Morocco which then expelled more than 80 civilian staff working for Minurso and closed a military liaison office, severely restricting its ability to function.

Minurso's mandate had been due to expire at the end of April but, with a day to spare, 10 of the 15 Security Council members voted to renew it for a further year. The renewal resolution (Resolution 2285) did not specifically instruct Morocco to rescind the expulsions but asked Ban Ki-moon to report in 90 days on whether Minurso had returned to "full functionality".

However, Morocco has already said that its decision to reduce staff at Minurso is "irreversible".

According to several reports, Resolution 2285 is a watered-down version of a draft originally proposed by the United States. The US is "penholder" of the Friends of Western Sahara group whose other members are France, Britain, Russia and Spain. The language of the resolution that was eventually approved appears to have been softened mainly at the behest of France and Spain.

American 'double rhetoric'

Although the stronger American version was not accepted by the Security Council, Morocco nevertheless took exception to it, accusing the US of "double rhetoric" and acting "against the spirit of the partnership that ties it with the Kingdom of Morocco".

Explaining Morocco's position, Samir Bennis writes:

"Unlike the practice in previous years, the US Mission to the United Nations submitted the draft resolution to the Group of Friends without consulting with Morocco. This prompted Omar Hilale, Morocco’s Ambassador to the United Nations, to express his displeasure with the US move.

"... the initial draft resolution was aligned with some paragraphs contained in Ban Ki-moon’s annual report on the Western Sahara in which he accused Morocco of hampering the mandate of Minurso after its decision to ask its civilian component to leave the territory.

"What caused Rabat’s disappointment is that the first draft addressed Morocco’s decision to request the departure of Minurso's civilian component without addressing the cause of that decision. In fact, the US administration overlooked the fact that the main cause of the friction between Morocco and the UN Secretariat is Ban Ki-moon’s biased statement ... in which he described Morocco’s presence over the Western Sahara as an 'occupation'."

Bennis adds that the American draft "contained punitive measures against Morocco and, if adopted, would have put Rabat under pressure and the threat of further coercive measures".

In raising these objections, Morocco seems to be trying to influence debates within the United States regarding American policy on Western Sahara (of which a recent article by former Pentagon official Michael Rubin is one example).

Bennis continues:

"The position adopted by the US administration in recent years reveals not only conflicting views within the same administration, but also that the relations between Morocco and the United States have not reached a level of maturity that would make them immune from any change of administration. Unlike its relations with France and Spain, which have adopted in recent years a clear position with regards to the conflict irrespective of the party heading the government, the US-Morocco relations are still tributary to the party at the helm of the White House.

"This is what prompted King Mohammed VI to say in his speech in Riyadh that Morocco has 'a problem because of frequently changing governments in some of these countries. With every change, significant efforts have to be exerted to introduce new officials to all aspects of the Moroccan Sahara issue and to make them aware of its real implications'."

However, the king seems to be assuming that once officials have been properly educated about Western Sahara they will necessarily support Morocco's position.

Posted by Brian Whitaker

Thursday, 19 May 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed