| The British-Yemeni Society |

|

Christian-Muslim

relations

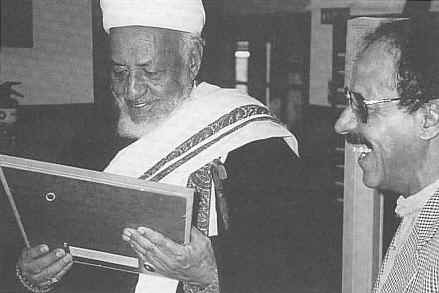

by BISHOP JOHN BROWN Until his retirement the author was Bishop in Cyprus and the Gulf. He is now Honorary Assistant Bishop of Lincoln. For many years he has heen actively involved in inter-faith dialogue. The following article is an abridged version of his talk to the Society on 12 November 1998. Introduction In the past twenty or thirty years there has been a growing awareness that to speak confidently, as in the past, of the Christian faith being the only path to God and eternal salvation, is to ignore a great deal of what is actually going on in the thought and practice of many who are not Christians. Christians who have lived and travelled in other countries have been unable to ignore the spiritual content in the lives, for example, of devout Hindus, Jews and Muslims; and this growing awareness of the presence of God in the lives of people of other faiths has compelled Christians to study the content and history of other religious beliefs and practices, and to take a deeper interest in the history of the Christian faith itself. Formerly, because of the compartmentalisation of life and the fact that it took many weeks (rather than the three or four days it takes today) to travel out of one culture into another, Christian government officials, traders and missionaries alike could confidently venture into uncharted territories with the union flag, account ledgers, order books, the English language and the Bible, and offer a complete package of prosperity education and salvation in Christ to the ‘ignorant’ natives. How rapidly things have changed, not only in the balance of politics and economics, but in our Christian understanding of the highly developed and far from ignorant belief and value systems of other religions. For many years, we (western) Christians have had to become accustomed to the reality that the quantity and quality of intellectual ability in the world is shared at least equally between white, black, Indian and oriental, and that in the western and northern hemispheres our lives have been much enriched by the artistic, literary, musical and spiritual genius of so many who are not only of different cultures, but of different religions. As with the Christian faith, we have learned very quickly that there are many colours to each of the different religions, and that it is quite impossible to speak of any religion as if it were monochrome, without diversity. Christians have been coming to terms with the ‘sin of disunity’ for years; and there are notable differences within Islam: not only between Sunni Islam and Shi’a Islam, but also within those traditions there are differences which have a profound effect on Islamic belief as well as on Christian-Muslim relations. The ancient Abu Hanifa school, for example, tolerates translations of the Qur’an from Arabic, and so predominates in the Indian sub-continent; but Muslims from Pakistan may still find their Urdu copies of the Qur’an confiscated by an over-zealous official should they enter the Wahhabi territory of Saudi Arabia. Muslim attitudes to Christianity: Historical One of the passages of the Qur’an most often quoted by Muslims wishing to impress their moderation upon Christians is in Sura 109:6 (Disbelievers): There is no compulsion in religion. There is another passage in Sura 10:100 (Jonah): You will find the nearest in affection to those who believe are those who say, ‘We are Christians’. That is because there are among them priests and monks, and because they are not proud. Of course, it is true that some Muslim leaders have shown more tolerance and kindness, especially in military victory, than others. A good example of beneficence is that of Caliph 'Umar during his conquest of Jerusalem in the 7th century. The Patriarch of Jerusalem surrendered to 'Umar in person and the Caliph would not enter the Church of the Holy Sepulchre. He made a treaty granting ... to the people of Aelia [Jerusalem] security of their lives, their possessions, their churches, their crosses ... They shall have freedom of religion and none shall be molested unless they rise up in a body. They shall pay a tax instead of military service ... and those who leave the city shall be safeguarded until they reach their destination. Similarly, Salab-ad-Din (Saladin) when he recaptured Jerusalem from the Crusaders in 1189 A.D., showed great tolerance towards the Christians in the city. These two examples are in marked contrast to the savagery shown by the Crusaders themselves in their dealings with Muslims. At the same time, the example set by 'Umar and Salah-ad-Din has not been consistently followed throughout the history of Islam. For example, it was commonly held during the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s that Saddam Hussain’s commanders deliberately placed young Christians in the front line, and there is some evidence for this. There is no doubt that the memory of the Crusades lingers in the Muslim mind, so that if we suppose that Islam’s emphasis on Justice and Right has often led it astray by its aberrations, we have to consider carefully and with penitence how often Christianity’s emphasis on love and forgiveness has been ignored and indeed destroyed through many centuries of strife and cruelty Muslim attitudes towards Christianity in the Arabian Peninsula Almost the last ten years of my frill-time ministry were centred on the states in the Arabian Peninsula, and I was able to compare attitudes there with my earlier experiences in Palestine and what is now Israel, in Jordan and in the Sudan. I learned in the Peninsula how important it is not to generalise about Islam and about Muslim attitudes towards Christianity. I have tried to show how full of variety the Muslim religion is, and now I have to underline that Muslim attitudes towards Christianity today are influenced more by political, economic and social trends than by theology. The most northerly part of the Arabian Peninsula is of course taken up by Iraq, which is a good place to begin this overview because it is the only country in the Gulf having indigenous Christians, apart from one or two families in places like Kuwait and Yemen. All other indigenous Arab Christians are to be found in the Levantine and Mediterranean countries, together with Jordan. The dominant Christian group in Iraq, centred on Baghdad since the 8th century, is the Nestorian Church or, as it prefers to call itself today, the Church of the East. This church follows the teaching of Nestorius who died around the middle of the 5th century, and is well established politically; the Patriarch is a man of influence even in the Iraq of today. The Ba’athist regime has no problem in accommodating Christian churches of different traditions, especially the Chaldeans, who are in communion with Rome (there is a Papal pro-nuncio in Baghdad), Arab evangelicals, Armenians, who have a Patriarch in Baghdad, and Anglicans. Under the Baghdad caliphate, from 651 AD. onwards, Christians have been regarded as people coming under Muslim protection (dhimma). A branch of the Church of the East known as the Assyrian Church has spread out from Iraq to Syria, Lebanon and the United States, where there is a Patriarch. There is no evidence of maltreatment of Christians, as Christians, under Saddam Hussain, and one of his chief ministers, Tariq Aziz, is well known as a Christian. In Kuwait the Christian church has a high profile, with a Roman Catholic cathedral with a Maltese bishop and a religious community of priests and nuns, an evangelical church and the Anglican church. The latter was built by the Kuwait Oil Company in the 1950s, and after the Gulf War was extensively restored. In Bahrain a similar situation exists, and there is an Anglican cathedral with a Provost and a daughter church some twenty five miles away in an oil town (Awali) on the archipelago. The Ruler of Bahrain maintains a personal interest in the life of the church. Qatar has as its neighbour mighty Saudi Arabia, and this makes it cautious about allowing Christians too high a profile. There are therefore no church buildings in Qatar, but the authorities do permit the residence of an Anglican and a Roman Catholic priest — the latter as a teacher, the former as a member of staff in the British Embassy. The Rulers of Abu Dhabi, Dubai, Sharjah and Oman all provided land for the churches which have since been built in those states. Yemen is in some ways the most interesting of all the countries of the Arabian Peninsula. This is because politically, economically and to some extent religiously it has been in a highly volatile condition since the end of the Ottoman Empire in southern Arabia, a condition also affected by the British presence in Aden from the mid-l9th century. Yemen is of great interest geographically and geologically, because of its high mountains and fertile valleys, as well as the oil reserves still to be exploited. In 1990, as we all know, north and south became united, and since then, apart from the very brief civil war in 1994, the Republic of Yemen has been grappling with the challenges of moving towards the twenty-first century. The southern part of the country is having to forget its twenty years of mismanagement under the Marxist regime of 1970-1990, and is trying to come to terms with its Islamic past, bearing in mind that different forces of Islam, such as Sufism, informed the southern style of Islam for a long time. Sunni Islam is now the spiritual force of the country, and so far it is proving tolerant and understanding of non-Muslim needs, especially of Christianity. Threats to the stability of Yemen today appear to result from the political and economic aspirations of tribes in places such as Marib, around Sa’ada in the north, and in some areas of the south. In each of the four chief cities ofYemen — Sana’a, Tai’z, Aden and Hodeidah — centres directed by the ‘Sisters of Mother Teresa of Calcutta’ have been doing wonderful work for many years. The Christian presence in Sana’a is very strong and is very much a lay-led movement. Baptist missionaries have worked for many years in hospitals in Sa’ada and in a village near 'Ibb north of Ta’iz. European Lutheran missionaries run a trade and craft school in Ta’iz. As far as the Anglican church is concerned, during my time as bishop I approached central government authorities in Sana’a as well as the Governor ofAden and others in the south, with a request that they should hand back to me one of the old Anglican church buildings that had been appropriated when the Crown Colony ceased to exist. I received nothing but courtesy, understanding and practical help from many people, both committed Muslims and those who were still Marxists. In the end I rejected all buildings as unsuitable except Christ Church, Tawahi, close to the harbour at Steamer Point. This was owned by the Yemeni navy and had been used for different military purposes, but it was still standing, albeit in a bad condition, and the date of consecration — 1862 — made it the oldest church building in the Arabian Peninsula by a very long way. One of the first subscribers to the fund that set the church up was Queen Victoria. My discussions about the handover of this property continued during the time of political transition, and it was the Grand Mufti of Yemen, Shaikh Ahmad Zabara, who finally clinched the matter by giving me a fatwa stating that the property known as Christ Church should be handed back and that Christians should be permitted to worship freely there, ‘just as Muslims are free to worship in the West’. This made all the difference and influenced those in the south who were full of goodwill but still conditioned by their Marxist pre-occupation with the god of bureaucracy. It also brought me into contact with the emerging influential Reform party known as Islah, and I had good meetings with the secretary-general of Islah in Sana’a. On our side I promised that we would do our best to build a medical clinic in the large church compound for the benefit of mothers and children (regardless of religious afilliation). All this was well on the way by the time I retired, and my successor, who is also experienced in Middle East affairs, has been able to complete the task, and the church and clinic are now fully operational with an international and inter-denominational team of church and medical workers. [for more detail on the Ras Morbat Clinic, Aden, see BYSJ Vol.5, 1997].

There is very much of a New Testament feel to everything which goes on in the church in the Arabian Peninsula, and in general it is fair to say that the Muslim authorities are well accustomed to accepting that many of the scores of thousands of Asian workers in Arabia are Christian, and need to have the proper facilities to practise their faith. In some Muslim countries pressure is brought on foreign Christian workers, especially those from Asia and Africa, to become Muslim, but it is only in Saudi Arabia, where Christianity is not recognised at all and where Christians are not permitted to practise their faith openly or in assemblies, that life for Christians is truly difficult. But it is important to understand why this attitude exists, and to understand is not to condone or justify it. The first thing to be said is that Saudi Arabia is the holy land of Muslims, having both Mecca and Medina within its territory. Christians are forbidden to enter these two cities and the surrounding area of pilgrimage, and the entire region constitutes a mosque (masjid = place of worship). But some Muslim authorities go further than this and claim that the whole of Saudi Arabia is holy ground and should be kept clear of an overt Christian presence in the shape of churches or an organised body of Christians. That Saudi Arabia contained many churches and monasteries in preIslamic days, and that these are well documented, is something many present-day Saudis do not care to recognise, and it has to be said that this attitude is far from that of the Prophet Muhammad himself, who was pleased to associate himself with both the Christian and Jewish presence in the Arabian Peninsula as he travelled the trade routes. The second thing to be said is that the House of Saud are very vulnerable to outside pressures. They are expected by all Muslims, and especially Shi’a Muslims as represented by Iran, to keep Saudi Arabia undefiled by non-Muslim influences. This of course was one of the reasons for the great outcry against the Gulf War by those who did not support the western-led coalition against Iraq.The Wahhabis are recognised as puritans within Sunni Islam, yet those in authority in Saudi Arabia are obliged to keep peace with the wider Muslim world including extreme Shi’a Muslims and Iran, and at the same time maintain important political and economic alliances with the United States and Britain. For these reasons among others, Christianity is not recognised in Saudi Arabia, and the situation there is the prime example of the need to avoid generalising about Muslim attitudes towards Christians. One of the most rewarding parts of my life as Bishop in Cyprus and the Gulf was the opportunity to have regular and frequent contact with Muslim rulers and religious leaders in the region. I vividly remember discussing the 16th century Reformation with Shaikh Saqr of Ras al-Khaimah; the question of the ‘sonship’ of Christ with the Grand Mufti of Oman; the evils perpetrated by religious extremism of all kinds with the Grand Mufti ofYemen; and humanitarian issues with the Crown Prince of Kuwait as well as with Rulers in the U. A. E. Much common ground is discovered in such conversations and improvements made to the lives of ordinary people, without any surrender of one’s own system of values. Christian Attitudes towards Muslims Before the Reformation of the 16th century the involvement of Christianity in Islamic affairs was spasmodic. The Crusader spirit regarding the Holy Places and pilgrimage was very strong and has never completely disappeared. On the other hand we may remember how influential were the Arab interpreters of Aristotle — Ibn Rushd and Ibn Sina, whose names were westernised into Averroes and Avicenna — in the medieval period and in the thought of St Thomas Aquinas and other Christian philosophers/theologians. Many Christians were undoubtedly concerned about the onset of Islam into Europe, and people like St Francis of Assisi felt that they had to be involved, at least to the extent of visiting and talking with Muslims.With the Protestant and Anglican Reformation of the 16th century came a new and perhaps more academic interest in Islam and the Arabic language, and printers in continental Europe, like the early one at Leiden, began publishing the Christian Bible in Arabic. These studies led some Christians to see Islam as anti-Christ and a sign of Satan’s onslaught, while others took the view that Islam was really a Christian heresy or an amalgam of Christian heresies. It was only perhaps with the advance of the missionary movements into the Indian sub-continent and the Middle East, as well as parts ofAfrica, that Christians began to realise that Islam was a religion with its own integrity and coherence, with its own self-contained scripture, its own traditions and its own legal structure. Conclusion: Christian-Muslim relations today In the past thirty and more years we may confidently say that a kind of industry has been built up in dialogue between Christianity and other religions, especially between Christians and Jews and between Christians and Muslims. All over the world, and especially in the United States, in Britain and in mainland Europe, academics, religious people and, latterly, people engaged in business and what might broadly be called the ethics of employment and trading, meet together to try to understand from one another what their value and belief-systems might have to say to them about daily living and the conduct of affairs. In the Vatican there are secretariats specially devoted to these purposes, and other churches, such as the Anglican, have bodies which link them with non-Christians. There are also institutions, such as the Ahl Al-Bait Foundation in Amman, Jordan, established and inspired by Prince Hassan; the Centre for Christian-Muslim Relations at Selly Oak, Birmingham; St Cross College in Oxford; The Three Faiths Forum jointly led by Shaikh Zaki Badawi and Sir Sigmund Steinberg; and dozens of others in American and European universities. Inevitably there is much duplication, but it has to be emphasised that these institutions dedicated to inter-faith dialogue are good examples of the truth that “jaw-jaw is better than war-war”. Those of us who have been engaged in such dialogue over many years have long since learned the fruitlessness of theological and dogmatic debate between different faiths. But there are matters of mutual and more practical concern which will occupy Christians, Jews and Muslims for a very long time to come: the whole area of family life, raising children, education and schooling, freedom of religion, famine, ethnic cleansing and many other matters. All this is going on at many different levels, from the United Nations in its various departments to central church organisations, to groups of people in local communities. In such ways, step by step, we move forward little by little, striving to rid ourselves of past misunderstanding and conflict, trying to abandon what Prince Hassan calls the stereotypes which make peace-making difficult, and hoping that such a prayerfully hard struggle will at length enable the children of Abraham — Jew, Christian and Muslim — to live together in peace, trust and mutual affection. December 1999 |