Yemen: Beyond the Horizon

Fernando Carvajal

The author is studying for a PhD at the Institute of Arab & Islamic Studies, University of Exeter. He has travelled widely in Yemen to conduct research on the relationship between tribal areas and central government within an emerging democratic environment. This article is an abridged version of his presentation to the Society at the Middle East Association on 16 October 2008.

My presentation will focus more on contemporary Yemen than on its history. I will attempt an overview of four main issues of contemporary interest before looking at the topic of change in Yemen and the importance of citizenship within the context of change.

I first visited Yemen in 2000, and for some time I have wished to present a new perspective on the country’s highly complex and interesting society. When we look at the available literature on Yemen’s culture, politics, anthropology and history, we find much about the past but not so much about the future. I believe that a discussion of the following four topics will help to throw light on the current situation: tribalism, economic development, politics and security.

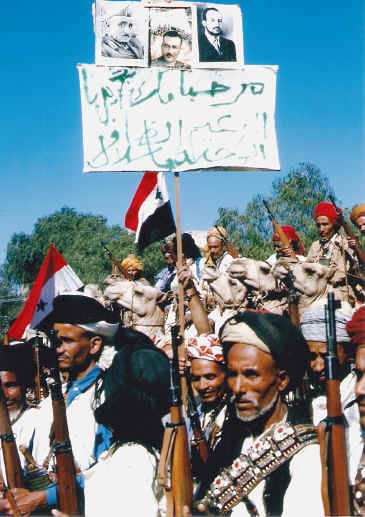

Academic studies on Yemen have accurately described the intricate relationship connecting all sectors of society, while most of us tend to pick tribalism as the point of departure for all discussions on Yemen. This approach is validated by proverbs which express the essence of Yemeni society such as al-yaman hiya al-qaba’il wa al-qaba’il hiya al-yaman (‘ Yemen embodies the tribes and the tribes embody Yemen’).

|

‘...Yemen embodies the tribes and the tribes embody Yemen.’ Photo: Bini Malcolm Collection, Middle East Centre Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford OX2 6JF |

Tribalism endures in the 21st century as more than a primitive form of social organisation. Tribes, we should remember, obstructed the absolutist ambitions of the Ottomans, maintained a border between the Imamate and the Aden Protectorate, and became the primary military force fighting the Revolution of 1962. This history served to strengthen the role of tribalism as a source of identity, and the position of tribal leaders as major sources of political and economic influence at the local and national level.

During Yemen’s modern history, that is from 1962 to the present, tribes have ended their isolation and entered the global scene. Their interaction with the outside world has been facilitated by migration, the presence of international organisations involved in rural development, the emergence and growth of modern government, and the information age of satelliteTV and the internet.

Today a strong sense of tribal identity seems to survive primarily in what is referred to as Upper Yemen. This is aV-shaped area extending northwest from the capital Sana’a to Sa’dah, and east from Sana’a towards Marib. In this area people proudly identify with their tribe not only in social relationships but in legal, economic and security matters. Today, tribes as political entities continue to present a challenge to central government, while the presence in their territory of the institutions of central government, be they military, administrative or judicial, represent a threat to the notion of tribal autonomy.

From an interview I had with Shaykh Abdullah bin Muhammad bin Sa’id al-Tayman of Sirwah, it emerged that tensions between the tribes and government were rooted in the latter’s failure to meet the former’s economic expectations. However, another factor is that the role of the traditional tribal leader (shaykh al-mashayikh) as an agent of reconciliation is seen to have been undermined by the State’s coercion of individuals against the interests of tribal populations.

History lives in the memory of tribes, and Yemen’s historical experience has proved the advantages of hostage-taking. Tribesmen believe that through kidnappings and the sabotage of oil installations they can pressurise the State and extract concessions from it in the form of basic services such as the provision of potable water, electricity, schools and medical clinics.

The death of Shaykh Abdullah al-Ahmar, paramount shaykh of the Hashid tribal confederation, in December 2007, has represented a turning point. For the first time in over 60 years Yemen will face a modern generation of tribesmen. In Shaykh Abdullah’s son, Hamid al-Ahmar, and in other young tribal leaders such as Shaykh Umar Hussayn Mujali of Sa’dah and the sons of Shaykh Abdullah al-Tayman, we can see the character of the new generation and their attitude towards the country’s new socioeconomic and political structures. But a priority concern for the new generation continues to be economic inequality and their share of the income from the exploitation of the country’s natural resources.

|

Tribal guard, AwwamTemple, Marib. Photo: Bini Malcolm Collection, Middle East Centre Archive, St Antony’s College, Oxford OX2 6JF

|

I do not believe that it is irresponsible to link many of Yemen’s problems to its prolonged economic crisis, and to the disappointment of popular expectations aroused by the oil boom of the 1970’s in the Gulf states. Surpassing the negative economic impact on South Yemen of the collapse of Soviet Union, and the devastating consequences of Yemen’s reaction to Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait, has been the loss of Yemen’s strategic location within the major shipping lanes connecting East and West. Today, ports which were once Yemen’s pride are overshadowed by Djibouti and Dubai. The loss of Aden and Hodeida as major ports in the region, has been an enormous blow to the economy of the most populous but poorest state in the Arabian peninsula, whose limited oil resources are already in decline.

Yemen’s efforts to attract foreign investment and aid from international donors have fallen short of expectations. Many observers blame corruption as a major obstacle to economic development, but there are many other factors, such as weak government, decaying infrastructure, diminishing water resources and increasing unemployment.

But against this must be set, as a potential sign of progress, the growth of private institutions of higher learning and the increasing number of students enrolled in state universities. Many of these young college students believe that they can contribute to the economic growth of the country through small enterprises, and these we are beginning to see in the technology sector. The fact that around 60% of college students are female and they are beginning to marry at a later age is another positive sign. Entry into the Gulf Cooperation Council (and access to the economic benefits of membership) remains a goal of President Saleh’s government, but this should be part of a comprehensive development strategy and not an end in itself.

This brings us to the third and fourth topic of our discussion, namely politics and security. In the area of politics, we should recognise the presence of two indivisible spheres: domestic politics and external pressures. I contend that these two spheres are indivisible, partly to distance myself from Ahmad Abdul Karim Saif ’s view in his book Politics of Survival that internal struggles are the main influence on Yemeni politics; and partly because I wish to focus on the impact of external forces on the course of Yemeni national politics today. For example, in the post-Unification period, with the introduction of democratic institutions, political mobilisation which previously depended on tribal forces is now conducted through competing political parties. In the run-up to the last presidential election in September 2006, most observers saw Yemen as unpredictable and unstable as ever. Yet the election passed without major incidents and a significant consequence was the emergence of the Joint Meeting Party (JMP). This new group brought together most if not all viable opposition parties and was led by Faisal Bin Shamlan as its presidential candidate. Unfortunately, however, the JMP failed to meet popular expectations as an effective organ of opposition. This may be inherent in the character of the party itself, composed of Islahis, Ishtirakis, Unionists and Nasserists with diverging agendas. While the JMP has been able to expose the government’s failed policies, it has been unable to present any compelling alternatives.

In this political environment, tribes continue to remain a relevant force. Evidence of this surfaced last year when in reaction to a meeting of the National Solidarity Council (NSC) convened by the Hashid tribes, the Bakil tribes, headed by Shaykh Naji al-Shaif, convened a separate assembly. The NSC’s initial resolution indicated that the tribes aspired to represent the disempowered voice of the Yemeni people. Politics in Yemen today, both local and national, are at a crossroads. Old institutions continue to gasp for air at a time when a new generation is looking to new strategies for political mobilisation but still finds it hard to limit the influence of traditional forces.

This situation has led to a steadily deteriorating security environment. There are three main areas of concern: insecurity as a consequence of tribal grievances; the impact of transnational political violence; and the rise in criminal activity (such as car theft and drug trafficking). Once again, I mention the tribal factor first simply because it is a fundamental element of Yemeni society. Kidnappings perpetrated by tribesmen, mainly against tourists or employees of foreign companies, represent a major obstacle to development at the national level. Yemen loses millions of dollars each year from donors or direct investment as a result of the negative image portrayed by media reports of kidnapped tourists. Furthermore, the increase during the last 24 months in transnational political violence directed against foreigners rather than foreign interests clearly represents a collapsing security environment. The failure to deter activities by ‘al-Qaeda affiliates or sympathisers’ within Yemeni territory has discredited the government both locally and in the eyes of the international community.

We now see a new dynamic in Yemeni politics – that of allegiances in contrast to the old dynamic of alliances. All political actors, whether islamists, tribal shaykhs or political parties, now struggle to win the allegiance of their respective constituencies. However, the challenge in Yemen remains one of turning ‘loyalty’ to the tribe (in its broad sense of family, place and history) into loyalty to the nation.

A number of American observers who have criticised the so-called pact between al-Qaeda and the government as a betrayal of the ‘War against Terror’ base their criticism on media reports rather than on-the-ground information which paints a different picture. In order to better deal with the challenge to nationhood of misguided loyalties, it will take more than shooting missiles from unmanned‘drones’or the imprisonment of hundreds of ‘suspects’. Government efforts to advertise youth summer camps and to enlist the support of organisations like the Boy Scouts implicitly recognise this. Last year’sYouth Festival in Sana’a, an event hosted by the Ministry of Youth and Sport, in which dozens of Boy and Girl Scouts took part, was very impressive. But programmes like this cost money, a cost to parents or government, and a lack of funding leaves young people vulnerable or too preoccupied with the need to support their families to participate.

The third issue affecting Yemen’s security is the rise in criminal activity. I remember in 2000 when I first visited Yemen how people spoke of Yemenis as warm and hospitable people. That is all you would hear from everyone, Yemeni and foreign. But since 2006 I have noticed that people increasingly point out instances of petty theft and more serious criminal activity, and caution visitors to be on their guard.

We now come to the topic of ‘change’. In my opinion there can be no greater obstacle to change than weak strategies for disseminating information, and this has been one of civil society’s major failures. Information is needed in remote areas, not just in urban centres, to bring tangible change totheaverage Yemeni. WhenIspeakofinformation, Imeanareal dialogue with the population. That is what the cooperatives of the early Revolutionary period aimed to accomplish, and was the avowed goal of the General People’s Congress but one which ultimately failed for lack of resources.

Dialogue can lead to a better (bottom-up) understanding of essential development needs in peripheral areas of the country. Also, while some urban centres are directly connected to the global economy, hundreds of villages remain isolated. When we think of change we must not only look for surface areas of opportunity, as many donors do, but we must also identify both agents and vehicles of change, and assist in developing them. This is where the JMP, for example, has failed to prove itself. When one asks Yemenis who else they see in the presidency, they cannot identify anyone with sufficient experience or political capital to take over. In the past century Yemenis looked to Imams, the military and the presidency as agents of change. While the Imams failed to implement change fast enough, the military filled the gap but soon exhausted their capacity. In the last decade of the 20th century the presidency brought about tremendous change but in this century it faces formidable obstacles.

Today, Yemenis, young and old, look for an agent of change. They are willing to follow and construct a constituency for those who emerge to fill the vacuum, but they realise that the vacuum cannot be filled by a political party or an NGO.

Another area where civil society has failed to construct an effective constituency is in the field of women’s rights. Even though I witnessed the major participation of women voters in the 2006 elections, they failed to identify themselves as a group constituency.

Constituency building is a major vehicle of change and by strengthening a sense of citizenship would help to promote greater individual responsibility.

In the book which he wrote in 1967 about his time in North Yemen during the Revolution of 1962, Scott Gibbons records an amusing incident from his first tour of the countryside arranged by President Sallal. His military guide, eager to demonstrate to foreign journalists popular acceptance of the new regime, asked an old man on the roadside what he thought of the revolution. The old man replied, al-hamdulillah, long live the revolution! The guide smiled at Gibbons, and then asked the old man what he thought of the Imam. The old man replied, al-hamdulillah, long live the Imam! As the guide ground his teeth in frustration, Gibbons laughs and thinks to himself, this old man doesn’t even know that there has been a revolution! Such is the environment within which civil society operates today.