The author, a member of the Society, is a journalist and

writer resident in Kenya. His father, Brian Hartley, CMG OBE,

served as Director of Agriculture, Aden 1938-1954, and was a

close friend of Davey who was killed in Dhala in 1947. Aidan

Hartley's forthcoming book, ‘The Zanzibar Chest: A Memoir of

Love and War’, will be published by Harper Collins in July

this year.

‘... In the corner of the veranda was a Zanzibar chest, carved

with a skill modern Swahili carpenters have forgotten. The old

camphor box bore a design of lotus, paisley and pineapple and it

was studded with rivets tarnished green in the salty air. When I

opened the chest lid, cobwebs tore and something scuttled into a

corner … Inside one file were my father’s handwritten

memoirs on which he had been working for years. I opened a

second file and reached down to grasp the pages. The instant I

touched them they began to crumble in my hands, Time, heat and

the drenching humidity had ravaged them … I began to read the

papers. I quickly realised I had stumbled on a secret that had

been buried for half a century. Here were the diaries of Peter

Davey, my father’s good friend. Ever since I was a boy, the

story of Davey crept in and out of conversation at home in

vague, half-finished sentences. The tale had always been there,

yet my father never properly talked about it. Davey was a

silence, a shadow that moved constantly out of the corner of one’s

eye. And now, as if it had been deliberately dropped into my

lap, here was the full and tragic rendition of Davey’s life

… ’

In this opening passage from my forthcoming book, ‘The

Zanzibar Chest’, I describe how seven years ago at home in

Kenya I stumbled by chance on the story of Peter Davey, the

Political Officer killed in a shoot-out when he attempted to

arrest Sheikh Muhammad Awas near the village of al-Hussein, west

of Dhala, on April 15th, 1947. The diaries turned up when I

found myself at a crossroads in life. My father Brian Hartley

(Director of Agriculture in Aden, 1938-1954) had recently died.

I had just left Reuters after covering a string of wars in the

Balkans and Africa culminating in the ghastly mess of Rwanda. I

wanted to travel and clear my head, and on the insistence of my

mother (Doreen Hartley, the Governor’s secretary in Aden,

1949-1951), 1 tucked Davey’s diary under my arm and set off

for Yemen.

Davey’s story is one of several somewhat unconnected tales

in ‘The Zanzibar Chest’, but I don’t yet feel I’ve done

justice to Davey. The only way to do that would be to publish

his diaries in full, illustrated with his excellent photographs.

Over the years I have received a great deal of help on my

amateur excursions into the colonial history of Aden - most

generously in London from Nigel Groom, who succeeded Davey as

Political Officer in Beihan, and his wife, Lorna, and from my

hosts in Yemen, Ahmed Hussein al-Fadhli and Brigadier-General

Sharif Haider bin Saleh al-Habili. But the project still faces

many challenges, not the least of which is finding a publisher.

Briefly, this is the story.

The saga of how the diaries survived at all is itself

remarkable. My father and Davey met in 1938. They became good

friends and shared a house in Sheikh Othman. They also worked a

great deal alongside each other, with Davey tackling political

matters and my father the agricultural. The diaries fell into my

father’s hands after he was dispatched by Aden with explosives

to demolish the fort of Davey’s assailant, Sheikh Muhammad

Awas. Davey, who had converted to Islam, was laid to rest in a

Muslim cemetery in Dhala. My father retrieved his personal

effects and he attempted to send all these to Peter’s mother

in Sussex. However, for reasons that remain a mystery to me the

diaries were never sent.

From then on, the diaries accompanied my family on its

adventures. Following my parents’ marriage, the documents went

with them to East Africa. First they were kept at their farm

near Mount Kenya The farmhouse was burned down during the Mau

Mau Emergency, but by that time the diaries had been transported

to Langaseni, my family’s new ranch on the slopes of

Kilimanjaro. Here they remained for seventeen years. When Julius

Nyerere’s socialist government expropriated the ranch, the

diaries were rescued once more. This time they went to North

Devon, where my parents had bought another farm. As a young boy

I first heard about Davey when I was briefly shown the

handwritten diaries, before they were locked away again in the

black tin trunk that sat in the office. In 1972, my father

deposited the original handwritten diaries in Rhodes House

library, Oxford. He had made a typed transcript of a portion of

the diaries in the 1940s. This copy was kept at our house in

Malindi, on the Kenya coast, and this was the copy I discovered

in the Zanzibar chest.

In the photographs Davey is blond, square-faced, and

athletic. His diaries are wonderfully written, packed with

contemporary flavour and incident. One of the most fascinating

aspects is to observe his transformation from naive youth to a

man utterly engrossed with life in the Aden Protectorate.

He commenced the first volume on October 6th, 1932. He was

17, he had just left Eastbourne College and it was the eve of

his departure by sea for the island of Perim, where his father

had been the manager of the coaling station since 1920. Perim’s

British community was big enough to field a cricket team for

matches against passing ships. Peter visited Mokha, French

Somaliland and also Aden, where he met the British Resident,

Colonel (later Sir Bernard) Reilly for the first time. Peter’s

ambitions were clear from the outset. ‘Dec. 3, 1932 - I am

trying to pick up as much Arabic as I can ... as I might be

joining the Palestine Police force. ’ He was rejected due to

his poor eyesight, so his father persuaded an American

entrepreneur named Klauder to take him on. Klauder was a

competitor of Besse in the hides and skins trade, in which Peter

was trained. The young man, who first lived in Crater, yearned

to get out of Aden. He earned three guineas while stringing for The

Times on the fighting between Imam Yahya and the Saudis over

the Asir in May 1934. He was later sent to Lahej, where he met

Wagner, a former comrade of Henri de Montfreid and now the

Sultan’s engineer, and in 1935 he visited Shuqra, Abyan, and

Dhala. In October the same year, Peter was dispatched to deliver

the first motor vehicle to Taiz.

Sir Bernard Reilly and Davey clearly got on well. ‘Pop’,

as Davey always called him, ‘is so very human. There is

nothing he likes better than to sit with a beer at his elbow and

yarn to people. ’ On February 23, 1936, Reilly asked Davey to

be his ADC. In this position Davey encountered a succession of

interesting figures, such as Freya Stark, and the Protectorate

Sultans when they visited Aden to pick up their stipends. But he

also got a chance to travel, notably with Reilly and Ingrains to

the Hadhramaut, where they dined at the house of Sayyid Abu Bakr

bin Sheikh al-Kaff in Seiyun with several hundred notables.

When responsibility for Aden was transferred from India to

the Colonial Office in 1937, Reilly, now Governor, advised Davey

that more ‘interference’ in Arab affairs was likely He

promised to try to get him appointed as a Political Officer.

Davey was not qualified in the eyes of the Colonial Office, but

Reilly pushed his proteges case hard and, after interviews, he

got the appointment and was posted to Beihan on October 18th,

1938. His initial task was to support Lord Belhaven’s

operation to recapture Shabwa from an invading force of Zeidis

under Ali bin Nasr al-Gardhai by gathering intelligence on their

movements. ‘I am thoroughly enjoying life now’.

In these first months in Beihan, he met Sharif Hussein and

his brother Awadh, Sheikh Qassim, Ali bin Munasser of the Bal

Harith, the various Musabein section leaders and the Abida in

their tents. Davey quickly grew to love getting about on

horseback or on foot. Like my father, he was in his element

travelling in the Protectorates. He loved nowhere quite as much

as Beihan. ‘Sept. 6th, 1942 - I seem to have many friends

there and Aden becomes, more and more, a place of strangers ...

From the Shabwa operations onwards, the pace of Davey’s

diaries barely lets up for a pause in this early phase of

Britain’s ‘forward policy’ in the Aden Protectorate. There

are border disputes and battles with the Zeidis all along the

frontiers. There are negotiations to end blood feuds, threats of

air action, bombs dropped from Vickers Vincents. We have desert

journeys to Al Abr and beyond, the consolidation of Sultan Saleh

bin Hussein’s authority in Audhali, long rides from Aden all

the way to Beihan via the Thirra Pass. He gives us marvellous

details of customs, dress, history and legend, gleaned from his

encounters along the way. An amazing succession of personalities

leap off the pages. Sayyid Ahmed bin Yahya al-Koblani, the Amil

of Harib, is ‘a little plump rat-faced fellow’. Basil

Seager, British Agent for the Western Protectorate, is ‘pedantic’

and ‘loquacious’, but a ‘nice enough fellow ... ’

My father and Davey worked together in various parts of the

Protectorate but with most a positive effect in Abyan. Here,

development of the agricultural potential of the delta had been

prevented by feuding, much of which focused on control of water

courses. Belhaven quotes a note in the Abyan file in Aden that

observed facetiously, ‘There is no way in which any of the

disputes can be settled, until everyone in the district is dead.

’ Finally, the Lower Yafai and Fadhli leaders signed their

truces and work to share the waters and restore the spate

irrigation system soon began to pay off By the 1950s,Abyan was

prospering from exports of some of the world’s highest quality

long-staple cotton. On my 1998 visit to Yemen, Ahmed Hussein

al-Fadlih and his friends kindly showed me around Abyan and

explained the history to me.

|

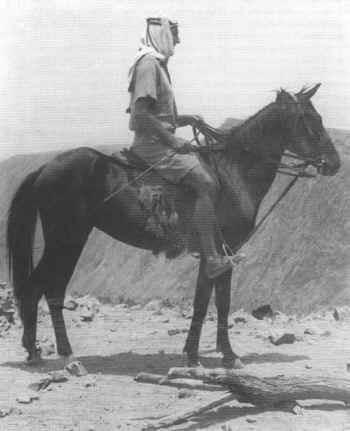

Brian Hartley on

his horse, 'Tunis' (given to him by Sharif Hussain), above

the Kaur escarpment, 1944. [Photograph: Peter Davey] |

The focus of Davey’s career as a Political Officer was in

Beihan. Having dealt with threats from the Yemen, Davey’s aim

was to restore peace in the wadi, with Sharif Hussein firmly in

charge. After a succession of dramas, he was able to write:

‘Sept. 22, 1943 - It is nearly five years since I came to

Beihan and in that period much of my energies have been spent

trying to persuade Government to take an interest in obtaining

security, in placing the Sharif at the head of Beihani affairs

and in trying to encourage the Beihanis to accept peace. Today

... this has to a large extent been achieved. ’

Of Hussein, Davey observed in 1944, ‘I could not wish for a

better friend, English or Arab, and I feel a genuine respect for

him,’ although he was not blind to Hussein’s cupidity and

ambition, which ultimately brought the two into conflict.

On February 24th, 1945, Davey wrote, ‘I have decided on two

momentous decisions. I am determined to marry an Arab girl,

which means that I will have to profess the faith of Islam ...

We have both become very, very fond of each other. ’ The

woman, Sheikha bint Mohsin, was a relative of Hussein’s. She

was also married. Davey was understandably worried about the

reactions of both the British and Arabs. Hussein put his mind at

rest, saying a marriage and the Englishman’s conversion to

Islam would bind them closer. As for the British, my father was

in Hadhramaut dealing with the famine and Davey decided to keep

it a secret - even from his own family Sheikha divorced. Sharif

Hussein oversaw the conversion - and Davey took the name

Abdullah. A few days later, on 28 March 1945, Davey and Sheikha

were married. To pay the bride price, Davey had to sell his

prized stallion ‘Kubeyshan’ to the Sharif for 250 silver

dollars. They set up in a new house, each of them buying in

goods dictated by custom: he had carpets, water skins and coffee

pots; she the rope of the camel, saddle bags, pillow cushions

and wooden food bowls.

Hussein could be impetuous and Davey fell foul of this in

1946 when the Sharif started to build a fort on a rock at the

head of the valley within view of the Yemeni frontier. Reports

of this got back to the Imam’s officials, who threatened to

break off all talks with the British if construction continued.

When Davey asked Sharif Hussein to suspend the work, the later

lost his temper and threatened to ‘resign’. Davey lay low

and after much mediation they were reconciled, All seemed to

have been settled by the time Davey left for Aden to go on long

leave. Hussein accompanied him.

Wednesday, March 6th 1946, Aden - The Governor [then Sir

Reginald Champion] has issued an ultimatum to me: that either I

divorce Sheikha or I shall be transferred. This is the hardest

thing I have yet experienced in my life I think … The subject

is so painful for me that it is impossible for me to write in

detail of the pros and cons but it is obvious that I cannot

continue with Sheikha as life would be made too difficult for us

both, officially and socially.

Davey did the only thing he could.

Thursday, March 14th 1946, Aden - I divorced Sheikha today in

the presence of Sharif Hussein and Sheikh Qassim Ahmed ... I

have been forced to divorce her and I feel as if I have been cut

in half but I have no way out of it as God knows. May He heal

the wounds in our hearts.

On leave in Britain, Davey visited old friends. He stayed

with Belhaven in Scotland in July, 1946, and also saw his mentor

Sir Bernard Reilly. During dinner at Quaglino’s with Reilly,

Davey told him that he planned to traverse the Empty Quarter,

from Beihan to Najran.

But instead, Davey returned to the life he knew best. In

October, 1946, he flew to Aden to be met by a relieved Seager (‘no

staff and a very incompetent Secretariat who are timid and even

lethargic ... ’). He was immediately posted to Dhala, where

rebellion against Amir Haidara had been fermenting. ‘The

situation in Amiri country is difficult due to mishandling by

Government. ’ Specifically, the Shairis had refused to pay

Haidara taxes. Under the terms of his treaty, Haidara had a

right to demand weapons from the British, which Seager gave him.

The Shairis fled en masse into Yemen, only to be coaxed back by

Seager with promises of compensation and independence. When a

charismatic young sheikh of the Ahmedi clan named Muhammad Awas

observed this, he led his own people in a fresh uprising.

Haidara blamed the British, withdrew to sulk in his castle on

Jebel Jihaf and within its walls began plotting.

Davey rode out to wave the flag soon after arriving. Muhammad

Awas received him warmly and Davey took an immediate liking to

the young leader. ‘Only by starting a complete new order can

Government hope to improve the political and economical welfare

of the people,’ Davey reported to Aden in January 1947. Seager

responded by calling for Haidara’s arrest and removal. Davey

swiftly persuaded the Ahmedi to join in the British operations.

On 8th February, Davey and a small force of Government Guards,

flanked by Muhammad Awas’s men, attacked the fort on Jebel

Jihaf, forcing Haidara to flee.

A conference of tribal sheikhs was called and despite Davey’s

advice, Seager ordered the Ahmedi to restore allegiance to Amir

Nasir, Haidara’s uncle. Awas was horrified. Having aided the

British, he had clearly expected the Ahmedi would be released

from the burden of Amiri taxation. He responded with a

hit-and-run attacks against Haidara’s family properties. Davey

was left with no choice but to enforce an unpopular British

policy He set off to arrest the sheikh.

On 15 April, 1947, Davey approached Muhammad Awas and his

followers as they sat chewing qat in the shade below their husn.

Clearly Davey mishandled the situation by attempting to

arrest the young sheikh in a way that would cause him an

intolerable loss of face. According to my father, Davey

exclaimed, ‘Sheikh, you have broken your word on keeping the

peace. I can no longer trust you, so I have come to arrest you!’

The sheikh yelled, ‘ Your mother lies!’ Ummak kadhaba!

Mayhem erupted, with both sides opening fire. A Government

Guard gunned down Awas, but not before the sheikh had shot Davey

in the chest. The Englishman staggered backwards;

when one of the sheikh’s retainers ran in among the group

and finished Davey off with a second shot, the same instant he,

too, was killed. It was over.

Brian Hartley arrived days later to destroy the fort. The

Ahmedi capitulated to the British, but the troubles in Dhala did

not end for years to come. My father wrote just before he died,

‘How tragic, how foolish and how wasteful the whole business

was ... I had lost a comrade, a friend of many years and many

trips. The government lost a fine man. Peter and Awas and his

loyal retainer had been killed. The fort was no more. I decided

there was nothing more to be done. Nothing of any good came out

of all of this ... ’ At Davey’s Dhala burial the Surat

Yasin was recited and the Government Guards fired a salute

over his grave. In a draft version of a letter to Peter’s

mother, written after the interment in Dhala, my father said:

‘Peter gave his life for an ideal and it was fitting that

his resting place should have been in such a setting, among the

people he worked for and mourned by his comrades.’

|

Davey's

assailant, Muhammad Awas al-Ahmedi. [Dhala Museum] |