| Cruise

ships are starting to call at Aden again, and tourists are

flying or driving to Aden as part of their tours of Yemen.

The old guide books provided by P&O liners and Murray’s

do not list much of what there is to see and do in

Aden; they concentrate on where to find the post office,

duty free shopping, sports facilities, the gardens at

Shaikh Othman, the ‘tanks’ in Crater, interspersing

such advice with snippets of local history and legend.

They mention little or nothing of the legacy of 130 years

of occupation (1839-1967) by the British and other

Europeans.

Historically, Aden town in Crater

had been a thriving entrepot of trade with Africa, India

and China. But when Captain Stafford Bettesworth Haines

seized it on 19 January 1839 on behalf of the East India

Company, for use as a coaling station for ships steaming

to and from India, it was a derelict village of some 600

inhabitants — Arabs, Somalis, Jews and Indians —

housed for the most part in huts of reed matting erected

among ruins recalling a vanished era of wealth and

prosperity. For Queen Victoria, the capture of Aden was

the first addition to the British Empire since her

accession to the throne in 1837. Haines’s knowledge of

Aden’s history made him optimistic about the

possibilities for its future. ‘Scarcely two centuries

and a half ago’, he wrote, ‘this city ranked among the

foremost of the commercial marts of the East the

superiority of Aden is in its excellent harbours, both to

the East and to the West; and the importance of such a

station, offering as it does a secure shelter for

shipping, an almost impregnable fortress, and an easy

access to the rich provinces of Hadhramaut and Yemen is

too evident to require to be insisted upon’.

Appointed Political Agent by the

Bombay Presidency of the East India Company Haines served

in this capacity (without leave) for the next fifteen

years, presiding over Aden’s rapid expansion as a

fortress (with a garrison of 2-3,000 Indian sepoys) and as

a port which by the early 1850s boasted a population of

some 20,000. Haines’s deep personal commitment to the

revival of Aden’s prosperity, despite the parsimony and

vacillation of his political masters, ultimately led to

his tragic imprisonment in Bombay for debt and to his

death (aged only 58) in 1860. But in South West Arabia his

name lived on and for decades local tribesmen referred to

the inhabitants of Aden as Awlad Haines (‘Haines’s

children’).

The house initially occupied by

Haines in Crater is said to have been rented from a local

Hindu merchant and to have been situated near a Hindu

temple. In his book Kings of Arabia (1923) H.F.

Jacob mentions, evidently quoting from Haines’s own

description, that it was ‘dilapidated, and parts fell

down on the concussion of the 8 p.m. gun. There was scanty

accommodation in his house for guests and he had to place

three to four gentlemen in one room, nor had he a room fit

for dining a small party; and so he put up a small

thatched building close by with a dining-room and two

small sleeping- or sitting-rooms. The largest room in his

residence was only 11 ft x 11 ft, and it was his

dining-room, and the servants [had] to pass through the

office to get to it, which [was] very inconvenient, as

both money and all records [were] kept there.’ Eleven

feet was about the length of the palm trunks locally used

for ceilings. In Sultans of Aden (1968) Gordon

Waterfield describes the building as ‘extremely hot and

the rooms inconveniently small’.

A map of 1875 places the

‘Residency’ in Crater near the Crater Pass. And one of 1877 marks it in the Biggari (later called Khusaf)

valley, south west of the Pass. A map dated 1917 calls the

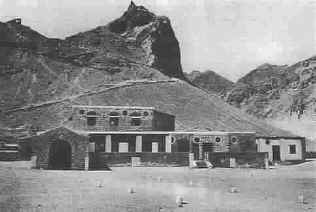

building ‘The Old Residency’. In Jacob’s book there

is a photograph (right), possibly taken some time before

he left Aden in 1920, of a long terraced stone building

with a roofed gateway and verandah, and with round

apertures in the walls above the doors and windows for

additional ventilation. Jacob describes this as

‘Haines’ Residence in Crater, now the Arab Guest

House’.

one of 1877 marks it in the Biggari (later called Khusaf)

valley, south west of the Pass. A map dated 1917 calls the

building ‘The Old Residency’. In Jacob’s book there

is a photograph (right), possibly taken some time before

he left Aden in 1920, of a long terraced stone building

with a roofed gateway and verandah, and with round

apertures in the walls above the doors and windows for

additional ventilation. Jacob describes this as

‘Haines’ Residence in Crater, now the Arab Guest

House’.

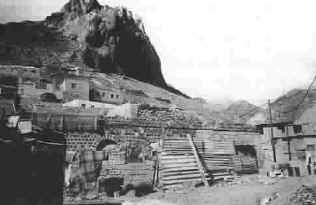

During a visit to Aden in February

1998, I set out to look for Haines’s house with the aid

of the old maps and some others dating from 1965, together

with Jacob’s photograph. The western end of Khusaf

valley is today an area of squatters’ shacks and it was

impossible to carry out a detailed search without

intruding into people’s living quarters. However, using

the alignment of the rocky outline of the hills in the

background of Jacob’s photograph, we found parts of a

stone structure similar to that depicted in the photograph

although partly hidden by concrete blocks, corrugated iron

and bits of packing crate (right). On returning to London

I learned that from 1948 until about 1954 Haines’s house

became the headquarters of the British Agency, Western

Aden Protectorate; photographs of the building taken in

the late 1940s show it virtually unchanged since Jacob’s

day

alignment of the rocky outline of the hills in the

background of Jacob’s photograph, we found parts of a

stone structure similar to that depicted in the photograph

although partly hidden by concrete blocks, corrugated iron

and bits of packing crate (right). On returning to London

I learned that from 1948 until about 1954 Haines’s house

became the headquarters of the British Agency, Western

Aden Protectorate; photographs of the building taken in

the late 1940s show it virtually unchanged since Jacob’s

day

Haines eventually built himself a

new, more suitable residence at Ras Tarshyne overlooking

‘Sapper’ Bay and ‘Telegraph’ Bay and with views

across to ‘Little Aden’. This was a more comfortable

house and his wife and child joined him there from Bombay

I am told that in the India Office Library there is a

watercolour of them standing on the wooden verandah of

this house. In the mid-1960s when I lived in Aden,

Government House as it was then called was a large, white,

very modern building commanding the same spectacular views

from Ras Tarshyne.

Although the area in Crater which

I have identified as the site of Captain Haines’s house

is not easily accessible to (nor suitable for) tourists,

there are many other places to visit: Sirah Island, for

example, with its fortifications and cannon, and the

fortifications around Crater which were strengthened and

rebuilt by Lieutenant John Western before his death in

1840.Western’s lone grave lies in Crater, below the

Legco Building (formerly the Garrison Church), and is in

danger of being bulldozed, as has happened to the other

graves in that first European Cemetery Ion Keith-Falconer

(1856-1887), the young Scottish orientalist and

missionary, who founded the Mission Hospital in Shaikh

Othman just a few months before dying of malarial fever,

is buried in Holkat Bay cemetery. He lived for a time in

Crater, near Crater Pass, and the site of his house can be

seen in old postcards. Other places to visit are the

historic Aidrous Mosque in Crater, the Museum on Front Bay

where the British landed in 1839, and ‘Telegraph’ Bay

where the telegraph cable linking London and Bombay was

brought ashore in 1870. Traces of the Grand Hotel de

L’Europe can be seen in the Crescent not far from the

famous landing stage known as the Prince of Wales Pier

(where all regimental and other plaques which once lined

the walls have disappeared). The statue of Queen Victoria

which also once stood in the Crescent is now lodged in the

garden of the British Council offices in Khormaksar.

Nothing is left of Aden’s old coal bunkers, but dhows

are still repaired on Slave Island and a few camels are

still employed in the haulage business in Crater!

In Crater and Steamer Point a good

deal of architecture from the colonial period survives —

reflecting Indo-Arab influences and the exigencies of

living in a hot, humid climate in the days before

electricity. Meanwhile, the European cemeteries in Crater,

Holkat Bay Barrack Hill, Ma’alla and Silent Valley

afford fascinating testimony of the many different

capacities in which the expatriate community lived and

served in Aden during its transformation from a derelict

village to a city of major commercial and strategic

importance, with a population, by the time of independence

in 1967, of nearly a quarter of a million.

November 1998

|