|

| Sound

Training Workshop |

| |

|

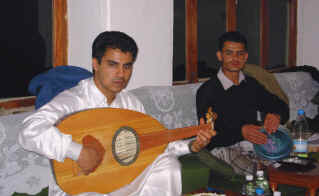

| Hasan al-Ajami |

Safeguarding

the Song of Sana'a: challenges and issues

by Samir

Mokrani

This article is based on an

address to the Society by the author, a musicologist, at

Goodenough College, London, on 23 November 2010

The Song of Sana'a: a brief

introduction

The Song of Sana'a or ghinâ'

san'ânî, is one of the main kinds of Yemeni music. It can

be described as a traditional urban genre, derived from various

poetic traditions dating from the 14th century, which

constitutes an integral part of social events, such as the samra

(night-long wedding celebrations), and the magyal, the

daily afternoon gathering of friends and colleagues at which the

mildly narcotic leaf qat is chewed. Thus, the Song of

Sana'a is a major component of the traditional urban elite's

culture, made up of musicians, poets, writers or just

connoisseurs. More than a kind of music, it represents a whole

micro culture, with its own social codes, aesthetic and vision

of the world.

The ghinâ' san'ânî is

performed by a solo singer who accompanies himself on the Yemeni

lute qanbûs/turbî or the Arabic lute 'ûd. He is

sometimes also accompanied by a traditional copper plate player

(sahn mîmyie/nuhâsî).

The UNESCO Action Plan and

its implementation

Mostly as a result of Jean

Lambert's efforts, the Song of Sana'a was proclaimed by UNESCO

as a Masterpiece of the World Oral and Intangible Heritage of

Humanity in 2003. Dr. Lambert was then in charge of writing an

Action Plan proposal, helped in this task by Sabrina Kadri and

myself; both of us were then trainee researchers at CEFAS (The

French Centre for Archaeology and Social Sciences in Sana'a),

where Jean Lambert had become the new director, and were

studying for our masters. The proposal benefited from a UNESCO/

Japanese Trust Fund which supported the project from 2006 to

2009, in cooperation with the Yemen Social Fund for Development

(SFD), the Ministry of Culture and CEFAS.

It was logical that the Yemeni

Centre for Musical Heritage(YCMH) was chosen as the official

implementing agency of the UNESCO Action Plan, and its director,

Mr. Jaber Ali Ahmed, was appointed as the National Coordinator,

while I was the Administrative and Scientific Coordinator.

The project's activities

encompassed the following:

- preparation and development

of an inventory of the Song of Sana'a;

- establishment of archives

within the institutional infrastructure of the YCMH and the

training of researchers in the techniques of field survey

and data collection;

- encouraging the transmission

of the Song of Sana'a, through the establishment of master

classes and scholarships for students;

- preservation of the musical

instruments through lute-making workshops, with scholarships

for students;

- awareness-raising campaign

and dissemination of recordings, together with the

production of promotional documentation such as CDs, DVDs

and books.

Mixed results: Issues and

problems faced by the executive team

The archiving constituent can

be considered as a success, as we managed to build a computer

database with more than 300 melodies. We also released an

official CD of archive recordings, and a history of the Song of

Sana'a is due to be published in a few months. However, the

results we obtained concerning the other aspects of the project,

namely the recording of living masters and musicians, and the

setting up of musical and instrument making skills transmission

workshops were much less positive, and this for the reasons that

are discussed below. Thus, we only managed to record a group of

traditional religious chanters (munshidîn or nashshâdîn)

and two living masters of the Song of Sana'a. On the

transmission side, the musical workshops were, to be honest, a

complete failure, while only two young men benefited to a

certain degree from the lute making workshops.

Work & personal

relations

First of all, and as a

preliminary remark, I would like to explain my personal

position. When I was appointed as the Administrative and

Scientific Coordinator, I built up a close friendship with two

men who were supposed to play a major role in the transmission

activities, namely the lute maker Fu’ad al-Qu’turî and the

master singer Hasan al-‘Ajamî. Up to a point, I was even

considering the latter as my master for learning the very

demanding tradition of the Song of Sana'a, as I had spent

several hours at his house singing, learning and chewing qât.

Unfortunately, I discovered that these personal links made

things much more complicated, particularly in regard to

financial matters, than if I had been an outsider;

unfortunately, my relations with these two men changed

considerably.

Music and musicians in

Yemen, a still ambiguous status

As to the failure of the

recording and the transmission activities, it is clear that the

still negative status of music and musicians in Yemeni society

played a major part. The dubious moral reputation of musicians

is partly due to religious factors (the Zaydi Imamate was always

quite strict on this issue), but also to a code of honour

related to the tribal social organisation specific to Yemen,

which, in our case, had direct consequences: the musician who

can be considered the last real traditional qanbûs player

and singer simply refused to be recorded or teach his music to

young musicians. For him, it was not music in itself that

appeared to be the cause of the problem, but his appearance in

public as a musician. He once told me an anecdote, which,

despite the fact that it relates to 20 years ago, is still

relevant today: ‘My father once told me: my son, this music

which I play and which my father played before me and his father

before him is a treasure, and I would be glad to teach it to

you. But if I hear that you have played it outside the house, I

will kill you!’

Transmission and competition

Regarding the tradition of lute

making, we were confronted with a very practical problem. Mr. Fu’ad

al-Qu‘turî (al-Gudaymî), identified as the last of the

old-style Yemeni lute makers, was quite happy when he first

heard that our project would support him by employing him as a

lute-making teacher. But after a while, as he considered that

the amount we could pay him for teaching was not enough, he told

me: ‘OK, if I teach three or four young people, then they will

be able to make turbî by themselves … and to sell them

as well. So in the long term, they will become competitors to my

own business … No, the only solution is that you pay me a big

amount in compensation for revealing my skills.’ Here we can

see all the dilemmas and limitations of our project.

Yemen, social changes and

globalization: an evolution of musical tastes

As a matter of fact and like

most traditional societies in the world, Yemen has been facing

huge socio-cultural changes for about 30 years, with a

particular peak in the urban areas from the 90's up to now.

These violent upheavals, of course, also occurred in the musical

field, resulting in notable changes in the younger generation's

musical tastes. Anyone who has spent some time in Sana'a, Aden,

Taiz or any other urban area in Yemen would immediately notice

that many young people, let us say between 10 and 40 years old,

frequently listen to Lebanese, Egyptian or Khalîjî

(Gulf) pop music. Certainly, this phenomenon increased with the

spread of television and more general use of the internet.

Despite this, however, local

musical styles still seem to enjoy quite a large success, with a

well-defined variety of characteristics or "colours" (alwan)

according to the person's origins and/or the place where he was

born and grew up. As for the Song of Sana'a, I would say that

the issue is much more related to the internal formal changes

that happened in the repertoire itself. What I mean here is that

the ghinâ’ san‘ânî that is sung today is not the

same as the one former generations used to listen to. From a

highly sophisticated music that can almost be compared to a kind

of initiatory tradition, it has become a popular music. The best

example is the adoption of the large Arabic ‘ûd in

place of the earlier, smaller qanbûs/turbî.

Thus, many young Yemenis told me: ‘Yes, the turbî is

nice, but the ‘ûd sounds stronger and better …’

Conclusion

It seems obvious that the

global conditions now confronting the Song of Sana'a are

unlikely to favour its preservation. However, although the

implementation of our Action Plan has been unable to avoid the

Song's progressive disappearance, the process has at least

stimulated a debate, and opened up new opportunities for action.

But only a genuine political will on behalf of those concerned

among the Yemeni authorities will achieve a real safeguarding

and promotion of this unique tradition.

Vol 19. 2011

|

| Samir

and Marwan, trainee musicians |

| |

|

| Muhammad

al-Juma |

| |

|

| Fuad

al-Qu'turi, Sana'a instrument maker, working on a qanbus |

|