| The British-Yemeni Society |

|

Winning

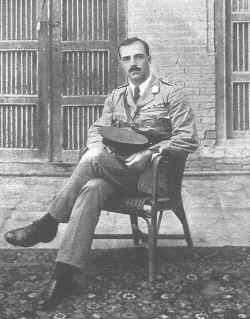

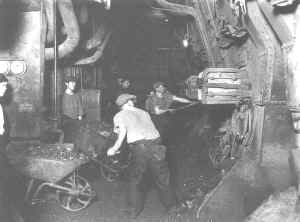

his spurs as a stoker by JOHN SHIPMAN Economic necessity obliged many Yemenis at the turn of the last century to make their living below deck in the steamships of foreign merchant navies. Few Europeans stationed East of Suez and familiar with the comforts of travelling on the passenger deck of P & 0, would have dreamed of sharing that harsh existence even temporarily. But Lieutenant (later Lieut-Colonel Sir Arnold) Wilson was an exception. In 1907, returning to India to rejoin his regiment, the 32nd Sikh Pioneers, after a spell of leave in England, the twenty-three year old Wilson disembarked in Aden to transfer to the P & 0 liner SS Peninsular for the final five day voyage to Bombay It was during this leg of his journey that Wilson’s curiosity in the hidden world below the passenger deck led him to spend ‘several hours in the engine-room and stoke-hold with a young Engineer from Bristol who was full of enthusiasm for his profession and took me, in an old boiler suit, to every part of his domain. ’

In a letter home from Aden, Wilson had commented that his fellow passengers were ‘more interesting and less blase, less rich but just as intelligent as those in the first class who dress for dinner and need a band to keep them from getting bored with each other’s company. I sit at table with a Wesleyan Minister from New Zealand . . . Between us are an actor and actress on their way to . . . Calcutta. The man is a simple-hearted Rabelaisian, the woman, about 24, unduly apprehensive of the intentions of young male passengers such as I. I had long talks with an English missionary going back to China and a batch ofjuniors in commercial houses who between them have quartered the East . . . The best of the lot are Australians and New Zealanders returning from the grand tour of England . . . They have made their own way in the world, and are rightly proud of it. ’ Wilson had sufficient time on shore to visit Aden’s tanks. ‘The great rainwater tanks are the only local monument of antiquity. They are hewn out of solid rock and lined with superb lime cement. The rainfall seldom suffices to fill them and the troops are supplied from a condenser. I climbed one of the barren hills. . , for a bird’s eye view more desolate than anything I have seen elsewhere: not a plant or a living bird or beast. The work of Aden is done by camels and Somalis, the hinterland is occupied by Arabs of whom we know nothing, though we have heldAden for the best part of a century. This is unlike us. We have taken steps to find out all we can of the language and ways of life of all our neighbours on the frontiers of India but anyone who tries to do the same here is rebuked or removed because, I gathered at the Club from an officer I knew, the government is anxious not to extend its responsibilities. They (the Arabs) come to Aden, but we do not go to them and, I am bound to add, they do not want us to come, lest "incidents" should end in "punitive operations". Aden is a bad station: there are more graves in the cemetery than beds in the barracks. There is nothing for the men to do and not much for the officers. I suppose we must keep troops here, but I should have thought Arab levies would have sufficed to hold the place till reinforcements came. And there is always the Navy. It is a good coaling station, and a convenient port of call for liners and was essential to us once the Suez Canal was built. I wish, like Palmerston, that it [the canal] had never been dug, for then our position in the Mediterranean and in the Indian Ocean would be more unchallenged than it is. ’ Towards the end of 1907 Wilson was transferred to the Indian Political Department and sent to the Persian Gulf where he was to serve as political officer, soldier and senior administrator until 1920. He then took early retirement to join the Anglo-Persian Oil Company as resident director in the Gulf. In 1913, having the previous year achieved the unusual distinction of being awarded a CMG at the age of 28, Wilson departed for some long postponed leave in England: ‘After a busy fortnight at Bushire I regretfully said farewell to Sir Percy and Lady Cox, but gladly saxv, from the deck of the mail steamer, the sandy wastes of Persia fade on the horizon. On my way down the Gulf I talked much with one of the ship’s engineers, a young Englishman from Oldham, whose broad Lancashire accent had attracted me when we first met some years before. I was full of superabundant physical energy. He suggested, laughingly, that I should stoke a ship home from Bombay, in order to try my strength to the limit. The idea took possession of me. It would save me the cost of my passage by P & 0 and put some money in my pocket - for I wanted to have something to spend when I got home. I induced him to help me to carry out this plan and swore him to secrecy. He fitted me out with a stoker’s overalls and clothes. I sent all my baggage home by long sea route through a shipmate of his . . . and took with me only a haversack. He found a tramp steamer of 6,000 tons or so about to leave Bombay for Marseilles via Suez, with a crew of British stokers who were short of one of their complement. The Chief Engineer was a friend of his and signed me on, understanding me to be ‘a young officer who was hard up and would not shirk the work’, which was bound to be severe as the monsoon had just started. I have kept no written record of this trip. I have even forgotten the name of the ship, but some details are vividly present to my mind nearly thirty years later. The quarters were rough and evil-smelling: no amount of labour on our part could improve them . . . We had to keep the portholes closed from Bombay to Aden, owing to the rough weather which added to our discomfort . . . The men were a rough lot, given to the use of words which are conventionally regarded as obscene, though nothing they said or thought was half so foul as the sort of chatter one may sometimes hear in the smoking-room of the first-class saloon. Their physique was not good: few of them were really physically capable of the strain which the work entailed . . . Exhaustion, increased by the unappetising food which was their lot whether at sea or on land, brought in its train a desire for strong drink. The seemingly endless routine of shifts and rest-periods, four hours on and eight hours off, night and day, seven days a week for seven weeks or more, predisposed them to seek solace, when they set foot on shore, in the temples ofVenus and Bacchus . . . They were all under 40, most of them under 30, for a stoker’s working life was short. I did not blame them for living for the present hour nor did their conversation . . . repel me. They worked, and did their best to live: they laughed easily, and were easily angered. But each of them bore the indelible marks of their harsh trade which was then recognised, in Mortality Tables, as one of the most dangerous to health and least insurable. We were ten days between Bombay and Aden; it was the height of the monsoon. I soon found out how to wield a shovel and how to spread the fine coal over the length of the grate. I learned to time my stroke to follow the pitch and roll of the vessel, and when and how to rake the bars. I took my turn at the ash-shoot and my watch with three other men, clad only in a pair of rope shoes to save the feet from being burned by hot ashes. At first my mates would not believe me capable of standing the heavy work: they ‘knew my sort’ - we always ended by going sick and having others to do our work. One man picked a quarrel with me, as a blackleg with a white collar, which ended in blows. I retorted that I would do a double shift to decide the question. That settled it: the others separated us and I did my double shift under the watchful eye of the charge-hand whose job it was to see that steam was kept up. At Aden a stoker went sick and had to be sent to hospital. The spirit of emulation was strong upon me: I would show them that I could beat them for once at their own dread and dreary trade. I asked the Chief Engineer to let me do double shifts to Suez, and to draw double pay for the extra shift. This would spare the other stokers and would avoid disorganising our regular shifts. He laughed me to scorn: I should do well if I could do single shifts up the Red Sea, for there would be a following wind, than which none is more trying in the stokehold. I retorted that if I failed to do double shifts to Suez I was willing to forgo the extra pay and would take the ordinary hourly rate for all overtime worked. He offered me pay and a half for the extra shift. This I refused: I would not be a blackleg. He laughed and agreed. I went back to tell my mates, some of whom offered to lay me four to one sovereigns I could not do it. I took the bets and gave the cook £1 to provide me with extra meat and a double help of whatever was going if I needed it, for I shonld have to work 16 hours a day - 8 on and 4 off twice the first day, and 4 on and 4 off the second day alternately till we reached the Canal.

It was the hardest ten days I have ever spent: I could not have stood the strain had not my mates, who had wagered four to one against me, made things easy for me when I was off duty. They put my mat under the wind-sail and made it easier to rest upon by laying two of their own mats below it. They brought me food into the stokehold when I was on the eight-hour shift and water as cool as the wind would make it. I stoked and ate and stoked again, went to doze or sleep and went down to the stiffing damp heat of the boiler room, forgetful of nights or days but spurred on by the sight of a chalked calendar on which we marked our progress. We reached Suez exactly on time: the Chief Engineer sent for me and shook hands. The Captain came off the bridge and said I was ‘a tough bugger’ - a word I reproduce without apologies for, in good English (or French), it is, as in Johnson’s day, a term of endearment. My brother stokers insisted on taking both my shifts through the Canal so that I might sleep undisturbed - in the Third Engineer’s bunk! At Port Said our bunkers were filled afresh and most of us had a night on shore. My mates declared they would stand me dinner, ‘and the rest’ on shore to celebrate the occasion. I had thought of trying to leave the ship here, but after this touching tribute I put the idea aside. It was my first complimentary dinner. None other has given me quite so much gratification. Stokers, even when as clean in body as soap and the hose could make them, were not welcome in the hotels and restaurants of Port Said, but one stoker ‘knew a good place’ - it was a brothel with a veranda on the ground floor, brightly lit with oil lamps. We were served with the best food we had tasted since we left Bombay . . . by a genial bevy of friendly young women whose lot was not more unfortunate than that of those whom they served. There was music . . . and song, though in languages which none of us could follow, from damsels in costumes which would have done no discredit to Les Folies Bergeres of Paris, beloved of staid matrons, fathers of families, and tourists . . . T. E. Brown has described the scene as I rememher it, in one of his poems: - Ripe orange, brushed From an o ‘erladen tree, chance-crushed And bruised and battered on the street, And yet so merry and so sweet! Ah, child, don’t scoff - Yes, yes, I see - you lovely wretch, be off? We left Port Said with a few headaches, but feeling that life was worth living a little longer. My mates offered to settle their wagers at four to one. I accepted two to one plus the dinner, and we parted good friends at Marseilles, where, after a roistering night on shore, I took my discharge, bought a cheap suit and a second-hand bicycle and rode across France to Le Havre, and from Southampton to my parents’ home in the Cathedral Close at Worcester. ’ Within a few days of his return,Wilson was donning a tail coat and top hat to call on officials at the India and Foreign Offices in Whitehall. Having so recently won his spurs as a temporary stoker, he doubtless relished the irony of being back in a world entirely alien to his ‘mates’. On the outbreak of the Second World War Sir Arnold Wilson (who had served in parliament as MP for Hitchin since 1933) joined the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve. An air gunner in Bomber Command, he was killed in action over northern France in 1940 shortly before publication of his book, S. W Persia: Letters and Diary of a Young Political Officer 1907-1914 (1941). The personality which emerges from the book, extracts from which have been quoted above, is that of a versatile, fearless and exceptionally gifted man who was at home in all walks of life, and in all circumstances. July, 2001 |