| The British-Yemeni Society |

|

Obituary

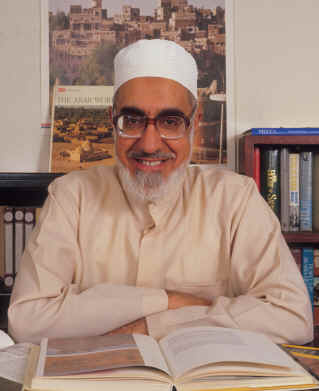

Sheikh Sa'id Hassan Ismail (1930-2011) Sheikh Sa'id Hassan Ismail who died on 23 March 2011 at the age of 81, was the Imam and leader of the Yemeni Community in Cardiff, where he lived for more than sixty years. Of the many tributes to him published in the Welsh media, that of the former First Minister, Rhodri Morgan, recalling his unique role in local public life, would serve as a fitting epitaph: 'His wise counsel at times of crisis has made him a truly significant figure in the shaping of modern Wales ...' He was born in South Shields in 1930 to a Welsh mother, with part Italian roots, and a Yemeni father from the region around Dhala. At the beginning of the Second World War, his father, then serving as a stoker on board the SS Stanhope, died when his ship was attacked by an enemy aircraft in the Bristol Channel and sunk. Hearing that the boy had lost his father, Sheikh Hassan Ismail, a leading Yemeni cleric, offered to take him back with him to Cardiff, and bring him up in the knowledge and understanding of Islam. Sheikh Sa'id recalled that his mother was not happy with this arrangement, but that 'the men persuaded her.' Sheikh Sa'id remained in Cardiff from that time onwards, except for a few years spent in his adopted father's village outside Taiz, immersing himself in the language and culture of the region. He claimed that without this period in Yemen, he would not have been able to accomplish much of his later work, preaching and teaching in the mosque and acting as arbiter in local disputes. During his time in Yemen, Sheikh Sa'id had the memorable experience of meeting Imam Ahmad whom he described as heavily built with great piercing eyes, holding court on cushions and carpets, surrounded by sacks of correspondence. Sheikh Sa'id later travelled widely in the Arab world to raise money to build the new South Wales Islamic Mosque and Community Centre in Alice Street, Cardiff, a project which he counted as one of the great achievements of his life. It was in Cardiff, once the largest coal exporting port in the world, that Yemenis often arrived to find work on the ships. 'The work of a stoker', Sheikh Sa'id recalled 'was always well paid'; indeed Yemeni seamen were paid enough to support whole villages back home where the cost of living was so much lower than in Britain. Men from many different regions of Yemen lived in the Butetown area of Cardiff, which in those days was like an independent township with a completely different character tothe rest of the city, and few Yemenis ventured outside its confines. Sheikh Sa'id could not remember any instances of ethnic tension or religious discrimination during his childhood; Muslims would celebrate Christmas, and the Welsh children would join in Muslim festivals such as Eid al-Fitr, at the end of Ramadhan. The Yemeni community were happy, he said, because they were a 'minority within a minority'. Throughout the twentieth century, the problems of Southern Arabia played themselves out within Cardiff's Yemeni community. Sheikh Sa'id once remarked that the latter knew more about what was happening 'on the other side of Taiz, than they did of Cardiff.' Welsh-Yemenis were often divided in their political opinions. There were those who followed Sheikh Hassan Ismail, Sheikh Sa'id's adoptive father, who supported the Imam, and those who followed Sheikh Abdullah Ali al-Hakimi, who published an Arabic newspaper harshly critical of the Imam and his feudal regime. It was largely due to Sheikh Sa'id's influence that the outbreak of civil war in Yemen in 1994 did not disrupt arrangements in Cardiff for a festival which the British-Yemeni Society helped to sponsor. Sheikh Sa'id took the view that whatever was happening in Yemen was a problem for the people there, and that 'we have to look after ourselves here in Britain.' His astute and gentle diplomacy prevailed. The festival went ahead and was recorded in a television programme which, coincidentally, was broadcast by MBC (Middle East Broadcasting) on the same day that hostilities in Yemen came to an end. As a devout Muslim, Sheikh Sa'id demonstrated the importance which he attached to deeds as much as to words by regularly visiting hospitals and prisons. The City of Cardiff's esteem for his services to the community was reflected in his appointment as its first Muslim Chaplain, the first such appointment by any City Council in Britain. He was aware of the sensitivities of being from a mixed race background, wryly observing that he was often 'either too white, or too black'. British since birth, he recalled the irony of being asked, during a visit to Aden, to leave the beach at Gold Mohur 'because he was not British.' Although he declined the offer of dual nationality, he was at heart both British and Yemeni, subject to his impish proviso that 'if Yemen ever starts playing Rugby, I will have problems!' The physical fitness which Sheikh Sa'id enjoyed as a younger man and a one time boxer did not last all his life, for he was later troubled by a kidney condition which in his last years compelled him to spend several days a week on dialysis. His met his first wife Gallila in Aden, following her abandonment and divorce by her then husband. They were childless so Sheikh Sa'id took a second wife, Wilaya, who bore him three children and survives him. Patricia Aithie |