Viewed in isolation, the temporary disappearance of Al Jazeera's Arabic-language Twitter account last Saturday might seem fairly insignificant. In the light of other events, though, it's yet another sign that political battles in the Middle East are increasingly being fought via the internet.

There's already a plentiful array of weaponry in use, from hacking and other forms of electronic harassment to politically-targeted phishing attacks, fake social media accounts, and robots programmed to deluge Twitter with propaganda or sectarian hate speech.

Exactly what happened between Twitter and Al Jazeera on Saturday is still not entirely clear. Twitter suspends lots of accounts, for all sorts of reasons, but it doesn't often suspend one like the Qatari broadcaster's @AJArabic account with more than 11 million followers. The suspension didn't last long, though, and normal service resumed later the same day.

Nobody is saying officially why this happened but the BBC suggests there was a massive and organised campaign of "abuse" reporting – in which case the account was probably suspended to bring that to a halt. Vexatious reporting of "abuse" is a familar tactic in social media warfare. In the Middle East, for example, Islamists have often used it to shut down secularist and atheist groups run by Arabs on Facebook (here and here).

But the Twitter affair was not the first strange thing to happen to Al Jazeera in the last couple of weeks. On 8 June it reported that all its websites and digital platforms were "undergoing systematic and continual hacking attempts". These attempts, it said, were "gaining intensity and taking various forms" but its platforms had so far "not been compromised".

Once again, this might not seem very significant when viewed on its own but appearances start to change when it's viewed alongside the bigger picture – of the most ferocious public quarrel the Gulf has seen for years. On one side of this affray, Qatar – home to Al Jazeera – is ranged against three of its Arab neighbours – Saudi Arabia, the UAE and Bahrain – on the other.

One of the more important demands these irate neighbours are making of Qatar is that it should curtail the activities of Al Jazeera and other Qatari-funded media. In anticipation of that, they are already preventing their own citizens from accessing Al Jazeera on the internet.

The feud with Qatar has roots in the past but the spark that set off the current altercation was a fictitious report of a speech supposedly made by Qatar's emir at a military ceremony on 23 May. The report appeared briefly on the website of Qatar's government news agency before the website went offline amid Qatari claims that the site had been hacked. The hacking seems to have since been confirmed by FBI investigators dispatched to Qatar.

In response to the fake report, Saudi and Emirati media – some of them insisting the emir's speech was genuine and that Qatari claims of hacking were merely an excuse – began an unprecedented tirade against Qatar and its emir. This paved the way for a series of measures by the Saudi, Emirati, Bahraini and Egyptian governments which, in effect, placed Qatar under an economic siege.

But the attacks have not been all one-way. At the beginning of June a collection of emails from an account belonging to the Emirati ambassador in Washington appeared on the internet. The leaked emails focused mainly on issues relating to Qatar and they seem to have been circulated with the intention of embarrassing the UAE.

The source of the email leak is unknown but suspicious minds might wonder if it was a reprisal by Qatar for the hacking of its website.

Around the same time, someone hacked the Bahraini foreign minister's Twitter account and posted tweets threatening Bahrain's royal family. It's unclear whether this was part of the quarrel among Gulf rulers or independent action by local opponents of Bahrain's repressive regime.

Russians and robots

All the electronic shenanigans described above fit within the timeline of what has now been dubbed the "Qatar crisis", and they have clearly helped to fuel it. In terms of international politics and diplomacy, this would be an extremely juvenile way for Gulf states to behave. But if Gulf states aren't doing it, who is?

An obvious – perhaps too obvious – suspect is Russia which, as we know from recent American and French elections, has a propensity for electronic mischief-making. Russia might also have a plausible motive: to set the GCC states at loggerheads, thus frustrating plans for an "Arab Nato" and indirectly boosting Iran.

There is some evidence of Russian connections, though it is rather thin. The Emirati ambassador's emails, for instance, were leaked via a Russian email address (easily acquired from anywhere), but that might simply be a smokescreen. In general, Russian internet services are also an attractive proposition for non-Russians wishing to avoid scrutiny.

Another possibility is that someone wishing to make mischief on the internet, but lacking the necessary expertise, might contract it out to Russian specialists. In that case, confirmed evidence of a Russian connection might not directly implicate the Russian government.

March of the Twitter bots

At the same time though, there is a vast amount of suspicious activity on social media which seems indigenous to the Middle East and unlikely to interest Russia.

Basically, this involves the creation of fake Twitter accounts, usually in large batches, which are programmed to post tweets in Arabic at pre-determined intervals. One aim of the tweets is to create an impression that Gulf regimes enjoy tremendous support from their loyal citizens; another is to encourage sectarianism amongst Sunni Muslims, directed at Shia Muslims and Iran.

The bulk of this activity, though by no means all of it, is associated with Saudi Arabia. Though clearly organised by government supporters, it may or may not be a government-run project.

Marc Owen Jones, currently a research fellow Exeter University's Institute of Arab and Islamic Studies, has been monitoring the use of Twitter bots in the Gulf over the past year and I have reported his findings in several previous blog posts:

Sectarian robots

22 June 2016

How robots have over-run the #bahrain hashtag on Twitter

23 June 2016

The automation of hate speech

29 June 2016

How Twitter robots spam critics of Saudi Arabia

28 July 2016

Interestingly, the Twitter bots have recently joined the fray over Qatar. Writing for the Washington Post's Monkey Cage section, Marc Owen Jones reported that just four days before the hacking incident an Arabic hashtag which translates as "Qatar is the treasury of terrorism" had been trending on Twitter. Further research showed that many of the accounts using this hashtag were non-human.

Following the leaking of the UAE ambassador's emails there was a further resurgence of activity by bots. Jones added:

"My analysis shows the presence of propaganda bots on numerous hashtags. One of these Twitter trends was #AlJazeeraInsultsKingSalman, and my analysis shows 20 percent of the Twitter accounts were anti-Qatar-bots. Many of them were posting well-produced images condemning Qatar’s relations with Hamas, Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood.

"Other images shared in the Twitter campaign singled out Qatar’s media channels as sources of misinformation. Almost all of the bot accounts tweeted support toward King Salman and Saudi’s new relationship with Trump. During the Riyadh summit [in May], these same bots posted thousands of tweets welcoming Trump to Saudi Arabia."

The technical data on which Jones's conclusions are based can be found on the Bahrain Watch website.

In his Washington Post article, Jones commented:

"What these bot armies represent is not an organic outpouring of genuine public anger at Qatar or Thani, but rather an orchestrated and organised campaign designed to raise the prominence of a particular idea. In the case of these bots, the intent appears to be legitimising the discourse that Qatar is a supporter of terrorism by creating the misleading impression of a popular groundswell of opinion.

"The fact that these bot armies existed before Qatar’s claims that they were hacked – and were in place quickly following the alleged hacks – indicate that an institution or organisation with substantial resources has a vested interest in popularising their criticism of Qatar. The purpose of this cyber propaganda may also be to shape the online discourse in favor of pressuring Qatar to abandon any thought of rapprochement with certain organizations or countries.

"Who is behind these hacks is unclear, but given that much of the bot propaganda appears to be the sewing of animosity between the Arab states and Iran, there is danger to regional stability if left unchecked. Twitter – once seen as an important resource for disseminating news across the GCC – may become a wasteland in terms of finding useful information from non-verified sources, undermining its usefulness as a tool for generating legitimate discussions.

"All the Gulf states have stringent freedom of expression laws that carefully control the Internet and the media – and monitor the behavior of their own citizens. Yet what’s interesting about the recent public display is that it highlights the use of cyber tools as forms of intra-GCC diplomatic warfare, tactics previously directed at countries like Iran, and not usually neighbouring Gulf states."

Malicious purposes

There's another illegitimate type of activity where Arab governments appear more strongly implicated – by circumstances, if not by hard evidence. It's known as "phishing" and the aim is to trick people into disclosing sensitive personal information, such as internet passwords, in order to use it for malicious purposes.

Phishing attacks are not uncommon and they are usually a fraudulent attempt to obtain money. However, several phishing operations discovered in the Middle East during the last few months have been unusual, since they were clearly motivated by politics rather than money. It is also hard to imagine why any political actor other than a government would want the information that was being sought. However, if Arab governments are orchestrating this, it's possible or even likely that they are using contractors to do the work.

Operation Nile Phish

Probably the most clear-cut of these operations – named by investigators as Nile Phish – occurred within the context of a government crackdown on NGOs in Egypt. An important part of that crackdown was Case 173, in which the government was prosecuting some of the country's most prominent and respected NGOs.

One example of Nile Phish's subterfuge was an email sent to NGOs in November last year, and dressed up to look as if it had come from one of their fellow NGOs, the Nadeem Center for Rehabilitation of Victims of Violence (since closed by the Egyptian authorities). The email was a fictitious invitation to take part in a panel discussion and it urged recipients to click on a link for more information.

The link, as investigators from the Toronto-based Citizen Lab later reported, "led to a site designed to trick the target into believing that they needed to enter their password to view the file".

Altogether, Citizen Lab documented more than 90 messages which it attributed to Nile Phish because they used the same servers and phishing tool. These messages, it said, targeted at least seven organisations, as well as a number of individual activists, lawyers, and journalists. Significantly, almost all of the targets were people connected with defendants in Case 173.

Citizen Lab stopped short of directly accusing the Sisi regime though it described the attacks as "yet another component of the increasingly intense pressure faced by Egyptian civil society" – pressure which was clearly being driven by the regime.

The Voiceless Victims affair

Another operation, last year, targeted people and organisations campaigning in support of migrant workers in Qatar, and was apparently intended to gather intelligence about them.

In design, this was far more elaborate than Nile Phish because it involved setting up a fake human rights group – "Voiceless Victims" – and creating false online personas for its purported members of staff. Internet postings by Voiceless Victims on its own website and on social media sought to create the impression of an active organisation – and one that was particularly concerned about the plight of migrants in Qatar.

Having established itself in virtual reality, Voiceless Victims then contacted genuine rights groups with a view to collaborating in campaigns about Qatar. However, it doesn't seem to have got very far – partly because Amnesty International became suspicious and launched an investigation after receiving an email from Voiceless Victims that contained links to a website previously associated with cyber-attacks.

I covered the Voiceless Victims affair in a series of blog posts last December and January, and readers who are interested in the details can look them up here:

Mystery of fake NGO that claimed to support Qatar's migrant workers

23 December 2016

Fake human rights group complains of threats

24 December 2016

Qatar and the 'Voiceless Victims' mystery

4 January 2017

The 'Voiceless Victims' mystery deepens

11 January 2017

Mysterious Qatar 'rights group' covers its tracks

22 January 2017

Although Voiceless Victims publicly criticised Qatar (probably in order to establish credentials) the most plausible supposition is that it was a Qatari intelligence operation. The Qataris, of course, deny that. In a letter to Amnesty, the foreign ministry said:

“After double-checking with all relevant government ministries and entities, we can categorically state that the Government of the State of Qatar has nothing whatsoever to do with the creation or operation of ‘Voiceless Victims’.”

Safeena Malik: mystery woman

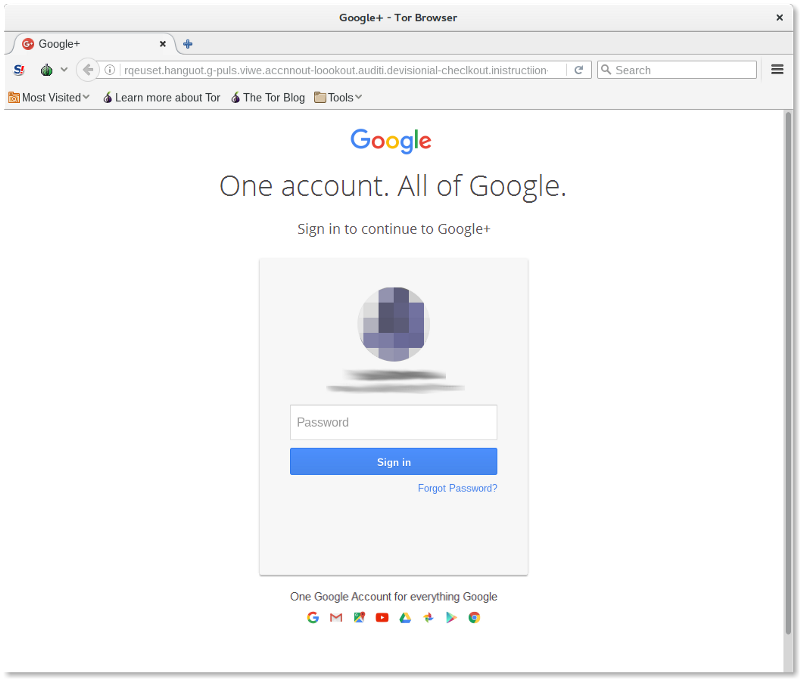

Qatar cropped up again in a phishing operation built around a fake character called Safeena Malik – supposedly a young university graduate carrying out research into human trafficking.

"Safeena", whose activities began in December 2014, established a veneer of credibility through social media accounts. On Twitter, she followed a large number of Middle East-based journalists, staff of international human rights organisations and trade unions, and various campaigns for migrants’ rights in Qatar. On LinkedIn she had more than 500 connections.

One of her techniques, described in a report by Amnesty International, was to start an online correspondence with the intended target, asking for help with her research and offering to share her own research with the target.

In the course of this correspondence she invited the target to view documents on Google Drive, and clicking on the links presented the target with what appeared to be a normal Google login page – except that it wasn't normal. It was a trick to obtain the target's Google password.

This particular phishing operation – dubbed "King Phish" by investigators because Malik's surname means "king" in Arabic – came with an interesting twist. Some of the compromised Google accounts were later accessed through an internet service provider in Qatar, raising suspicions that Qataris were behind it. The government of Qatar, however, emphatically denied any involvement: "We consider such practices to be unethical and would regard them as a clear violation of our government's principles and values."

Amnesty commented:

"While there is a clear underlying Qatar migrant workers theme in this campaign, it is also hypothetically possible that these attacks could have been perpetrated by a malicious actor affiliated to a different government with an interest in damaging the reputation of the State of Qatar.

"However, in the absence of clear evidence, trying to identify the entity behind this attack can only be speculative. As such, we cannot make any conclusive attribution."

Phishers spread their net

In an article for Bellingcat last week, Collin Anderson and Claudio Guarnieri described yet another phishing operation, known as Bahamut, which appears to be larger and technically more sophisticated that any previously seen in the Middle East. It is also very puzzling because of the diversity of its targets. Anderson and Guarnieri write:

"What makes Bahamut novel is not their techniques but their interests. Across our brief windows of visibility into their activity, there is a consistent set of fundamental interests that suggests political espionage rather than economic motivations. Bahamut is not an ordinary cybercrime campaign. Through directly reported phishing incidents, artifacts harvested from their infrastructure, and other public records, Bahamut appears to be a sustained campaign focused on diverse political, economic, and social sectors in the Middle East."

Identified targets have been located in Egypt, Iran, Palestine, Turkey, Tunisia, and the UAE, and the writers give some specific examples:

Arab Middle East:

A financial services company focused on wealthy clients with a desire for “confidentiality”

Egypt-focused media and foreign press

Multiple Middle Eastern human rights NGOs and local activists

The Emirati Minister of State for Foreign Affairs, an Emirati diplomat, and the head of an Emirati foreign policy think tank

A prominent Sufi Islamic scholar

The Union of Arab Banks

Turkey:

A Turkish delegate to UNESCO

The Turkish Foreign Minister

Iran:

A relative of the president of Iran

An Iranian women’s rights activist and a prominent female journalist in the diaspora

A reformist Iranian politician who is an adviser to the former President Khatami

If this is the work of a government, the question it raises is: which government? The report's authors comment: "Few state interests would convincingly account why someone would engage in espionage against Egyptian lawyers at the same time as Iranian reformists." This, they say, leaves open the possibility that the operator is "a non-state actor with diverse motivations".

They add that regardless of who is behind it, "the operation’s ambitious attempts against Arab foreign ministers and civil society, and dozens of others, warrants special interest. These incidents also reflect current tensions among Gulf states, undergirding the ubiquitous and central role of cyber espionage in Middle Eastern statecraft."

The Anderson/Guarnieri report on Bahamut is detailed and very technical in places, but it also contains some fascinating examples of tricks used by the phishers to avoid detection.

More dodgy domains

While exploring Bahamut's technical infrastructure, the investigators came across four other internet domains which were clearly not legitimate and appeared to be connected with it in some way (though the connection is not proven).

One was an old copy of a website linked to al-Qaeda – Al Fajr Media Center – which also included encryption software known as Amn Almujahid ("Security of the Jihadist"). The investigators offer no explanation for this.

Two other domains contained mobile phone apps. One was "a fully functional Urdu-language Quran application" called 16 Lines and the other, called Khuai, was an app for translating from Chinese to English. Not surprisingly, both were designed to extract information from the user's phone.

A weird 'news' website

The fourth domain contained a bizarre "news" website with the ungrammatical title "Times of Arab" which promised "to bring substantial news to the surface, which is otherwise underreported by the global media". Its mission satement continued:

"Our journalists ensure the stories that reach you are impartial and unaffected from any sort of vested interest. We want to reshape the world media by strengthening our bond with the readers, a bond formed with trust and truth ..."

Its content, however, was utterly weird and sometimes nonsensical. Articles were copied from elsewhere, often with headlines or pictures that didn't match. Some of the material seemed to have been chosen unread, based on a keyword search. One article, for example, had a headline about the Arab Spring but the text beneath it reported basketball game held during the spring in an Alabama town called Arab.

This highly entertaining publication was launched last January but, sadly, is now closed. A note on its website says "Account Suspended", though its Twitter feed can still be seen.

But what on earth was the purpose of "Times of Arab"? That, as Winston Churchill once said of Russia, is a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed