While there is much debate about the rights of women in the Middle East and the rights of gay and lesbian people have also begun to attract some attention, consideration of transgender rights is long overdue.

In a region where gender segregation is widespread and dress codes are sometimes enforced by law, the problems of transgender people are especially acute. When so much of the social structure is based around a clear-cut distinction between male and female, anything that obscures the distinction is viewed as a problem and sometimes even as a threat to the established order.

This is the first in a series of "long read" articles which aim to give a broad but detailed overview of transgender issues in the Middle East.

The complete series can also be downloaded as a printable 23-page PDF.

- Part 1: Crossing lines

- Part 2: A history of ambiguity

- Part 3: Making the transition

- Part 4: Struggles for recognition

1. Crossing lines

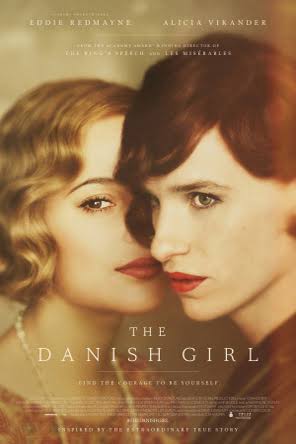

In Qatar during the first few days of 2016 several cinemas began screening The Danish Girl – a film about a transgender artist. Almost immediately, complaints appeared on social media and the Culture Ministry, thanking Twitter users for their “unwavering vigilance”, announced that the film was now banned.

It had already been blocked by censors in the United Arab Emirates, Oman, Bahrain, Jordan and Kuwait. In Saudi Arabia the question of a ban did not arise, since in the interests of morality the kingdom has no cinemas.

Meanwhile, in a more positive development, a Lebanese judge ruled that a transgender man could have his sex changed in the official records. In some parts of the world this is a very straightforward procedure but in Lebanon it means going to court – in this case the Court of Appeal, since a lower court had already rejected the application. Transgender Lebanese are relatively lucky though. In most of the Middle East there is no established mechanism for registering a change.

Local activists welcomed the Lebanese ruling as a modest step forward for transgender rights in a region where the crossing or blurring of gender boundaries usually meets with disapproval. Even in Lebanon, by no means the most prudish of Arab countries, more than 80% of the public regard anyone who cross-dresses as “a pervert”, according to a national survey, and 18% “would consider being physically or verbally abusive" if they encountered a man in the street dressed in women’s clothes.

While there is much debate about the rights of women in the Middle East – or rather, the lack of them – and the rights of gay and lesbian people have also begun to attract some attention, transgender rights are still largely ignored. That is an omission which needs to be addressed: when gender segregation is widespread and dress codes are sometimes enforced by law, the problems of transgender people are especially acute. When so much of the social structure is based around a clear-cut distinction between male and female, anything that obscures the distinction is viewed as a problem and sometimes even as a threat to the established order.

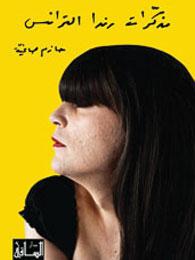

Given that background, it’s scarcely surprising that trans people in the Middle East generally keep a low profile, though there have been a few exceptions. One was Randa, a trans woman who fled from Algeria to Lebanon and whose battles for acceptance were recounted in a book, “Memoirs of Randa the Trans”, published in Arabic in 2010. Morocco also has a celebrated transgender belly-dancer known as Noor Talbi. Most, though, remain anonymous and if they come to public attention it’s usually through conflict with the law.

"Memoirs of Randa the Trans"

Some terminology

“Transgender” (often shortened to “trans”) is a very broad term for a variety of situations and behaviours – and also gives rise to a lot of confusion. So before going any further it’s important to clarify some terms.

Transgender women are people who were designated male at birth but who identify and may present themselves as women. Conversely, transgender men are people designated female at birth but who identify and may present themselves as men.

At birth, children are classified as male or female – usually based on examination of their genitals. This is recorded on their birth certificate and will normally remain unchanged throughout their life. However, external sex organs do not always give a clear indication and they are not the only factor in determining biological sex: unseen elements such as chromosomes, hormones and internal reproductive organs also play a part. People who are not clearly male or female used to be known as hermaphrodites though the preferred term nowadays is intersex.

Aside from biological sex, gender is a social and cultural interpretation of what it means to be “masculine” or “feminine”. It has both internal and external components. Gender identity is a person's internal, deeply felt sense of being male or female (or something in between, or neither). Gender expression is how people manifest characteristics that society has defined as masculine or feminine – through clothing, appearance, mannerisms, behaviour, etc.

A mismatch sometimes occurs between a person’s gender identity and the sex they were assigned at birth. This can cause discomfort or distress, often described as a feeling of being “a man trapped in a woman’s body” (or vice versa); it is a recognised medical condition known as gender dysphoria, for which treatment is sometimes – though not always – appropriate.

The aim of any treatment for gender dysphoria is to minimise the mismatch. For some people it can mean changing their appearance (clothes, hairstyle, etc), adopting a different name and seeking to have these changes recognised both socially and officially. Sometimes this is accompanied by hormone therapy and may culminate (though not always) in sex reassignment surgery. Transgender people who have undergone surgery, or who are preparing for it or taking hormones, are often described as transsexual.

Aside from that, there are people who may be content with the sex assigned to them but whose gender expression does not conform with the usual expectations of their culture: men who are considered too feminine, women who are considered too masculine. There are others, too, whose gender identity is neither male nor female. Further complicating the picture, there are also cross-dressers: people – often heterosexual – who may be comfortable with their gender identity but get pleasure from sometimes dressing in clothes associated with the opposite sex.

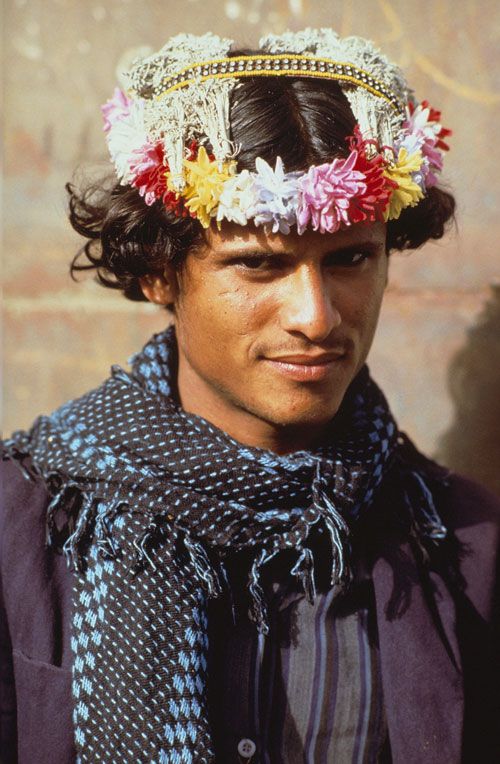

Ideas about what constitutes “normal” male or female attire vary, of course, according to time, place and culture. One striking example is the men of Habala in south-western Saudi Arabia who traditionally wear head-dresses of herbs and flowers. To outsiders, including Saudis from other parts of the kingdom, this might look effeminate but for them it is normal male attire. Contrary to appearances, they also have a reputation as fierce fighters.

"Flower man" from Habala in Saudi Arabia

The proper way to dress

Upholding “proper” dress codes is a particular concern of some Islamic scholars. In his book, "Lawful and the Prohibited in Islam", Yusuf al-Qaradawi quotes the Prophet as saying that “a woman should not wear a man’s clothing or vice versa”. Qaradawi continues:

“The evil of such conduct, which affects both the life of the individual and that of the society, is that it constitutes a rebellion against the natural ordering of things. According to this natural order, there are men and there are women, and each of the two sexes has its own distinctive characteristics. However, if men become effeminate and women masculinised, this natural order will be reversed and will disintegrate.”

Examples of imitating the opposite sex “include the manner of speaking, walking, dressing, moving, and so on,” according to one Muslim website. While cross-dressing in an Islamic context might conjure up images of veiled men draped in black abayas, “scholars” of a particularly rigid-minded disposition have laid down extraordinarily detailed rules about what constitutes masculine and feminine attire – rules which often have a dubious basis in scripture.

According to Muttaqun Online, which actually used the phrase "unlawful clothing" in its explication of the rules, men's clothes should cover the whole body but not reach below the ankles, and must not be tight-fitting. White and green are good colours for men to wear but red is bad, unless mixed with another colour, and men should not tuck their shirt inside their trousers. Beards, unsurprisingly, are obligatory for men and must not be trimmed (though the moustache part should be cut). Religious considerations aside, Muttaqun cited health benefits for this, saying: "Medical reports reveal that the beard protects the tonsils from sunstroke".

There are warnings on other websites against men wearing “feminine” types of cloth such as silk, or gold jewellery (though silver may be acceptable). Feminine dress includes male neck-chains, bracelets and earrings according to some.

In contrast to that, it’s worth noting that Egyptian cinema, which developed in the 1920s and is popular throughout the Arab region, has shown little inhibition about portrayals of cross-dressing in films. Disguising men as women, and vice-versa, creates situations that can be easily exploited for comic effect and can also be used for more serious purposes such as highlighting social inequalities between the sexes.

While some of this cinematic cross-dressing provided a convenient theatrical device, other examples were coded (if inaccurate) references to homosexuality. “Cinematic references to gays and lesbians abound,” Garay Menicucci wrote in an essay on homosexuality in Arab films. “The most ubiquitous coding for gay and lesbian cinematic imaging has been cross-dressing.” For the most part, though, these characters seem to have been included for entertainment value or decorative effect, rather than to make a point.

In an interview with the French newspaper, L’Humanité, prominent Egyptian film director Yousri Nasrallah commented:

Many popular films – mostly comedies – show homosexuals. Most often, effeminate characters, transvestites. This image of the homosexual is tolerated perfectly. It makes the public laugh and, in a way, confirms the ideas they have about virility. On the other hand, they are much more reticent when it’s about a ‘normal’ homo – loving and successful.

Enforced dress codes

Saudi Arabia has a long history of enforcing dress and behavioural codes through its religious police, the Committee for the Promotion of Virtue and Prevention of Vice. While the excesses of the religious police have made them very unpopular inside the kingdom, the last 10-15 years have seen attempts to copy the Saudi approach elsewhere – moves which are probably a result of increased religiosity and the growth of identity politics.

In 2007, the Kuwaiti parliament amended Article 198 of the country’s penal code so that anyone “imitating the opposite sex in any way” could face up to a year in jail and/or a fine of 1,000 dinars ($3,500). The way this came about is quite revealing. In 2006 Waleed al-Tabtabai, an Islamist MP, formed an ad-hoc committee in parliament for the “Study of Negative Phenomena Alien to Kuwaiti Society”.

Although the committee was supposedly only carrying out studies it proposed a host of “morality”-related measures in parliament, including the amendment to Article 198. Many of these were vigorously resisted by more liberal members but in the vote on criminalising imitation of the opposite sex the 40 MPs present agreed to it unanimously. “The issue,” Human Rights Watch commented in a subsequent report, “was seen as insignificant in the larger political battle.”

The effect if this was to criminalise all transgender Kuwaitis. Although the health ministry had recognised Gender Identity Disorder (now known as gender dysphoria) as a medical condition there was no way that trans people could change their legal identity. Thus, even people who had undergone surgery were deemed to be “imitating the opposite sex”.

A further problem was that the law made no attempt to define “imitating the opposite sex”: it was basically left to the discretion of the police. Within a couple of weeks at least 14 people had been arrested in Kuwait City and thrown into prison for the new offence. Several were picked up at police checkpoints, one in a coffee shop and two more in a taxi. A Kuwaiti newspaper said the “confused” men were “deposited in the special ward” of Tahla prison, and that prison guards shaved their heads “as a form of punishment”. Citing friends of the accused, Human Rights Watch said three of them had been beaten (one of them into unconsciousness), and all denied access to lawyers.

Shortly afterwards, the United Arab Emirates followed Kuwait’s example with its own war against “imitating” the opposite sex. In 2009, Dubai launched a public awareness campaign under the slogan "Excuse Me, I am a Girl", which cautioned against “masculine” behaviour among women and aimed to steer them towards "femininity". The impetus for this was a moral panic which swept through several Gulf states at the time regarding the boyat phenomenon.

Boyat (the English word “boy” coupled with an Arabic feminine plural ending) became a general term for women or girls displaying masculine traits in their dress or behaviour. Some identified as lesbian or transgender but others did not and in some respects boyat seem to have been a kind of youth subculture. Most importantly, though, they were deliberately challenging traditional gender norms, which helps to explain why they caused so much alarm.

The region’s largest round-up of boyat appears to have taken place in Saudi Arabia in 2013 when the religious police raided a party at a hotel in the eastern city of Khobar. According to the authorities it had been organised "under the cover" of a graduation party, with about 100 young women attending, and included a contest for the best-looking boya. The police seized a crown which had been due to be presented to the contest winner, along with a large quantity of energy drinks and "Satanist" items. Reports said a man and a woman who organised the party were arrested but most of the girls were handed over to their parents.

In Dubai’s anti-boyat campaign, plainclothes policewomen were deployed in shopping malls to watch for violations of female dress codes and, as might be expected, there was much public agonising over what made once-sweet young girls behave in this way. Dubai’s police chief blamed co-educational schooling while others blamed inadequate parenting. These debates usually took place against a background of very confused ideas about gender and sexuality, often equating cross-dressing with homosexuality and failing to distinguish between cross-dressing and transgender.

The crime of cross-dressing

In 2010, Dubai launched another campaign – this time encouraging the public to report cross-dressing “crimes”. According to officials, it was prompted by cross-dressers “becoming bold in public places” such as toilets and beauty parlours. A police official urged people to dial 999 if they spotted anyone cross-dressing. It didn’t matter whether the cross-dressing was causing a problem or not, the official said, because “dressing up as women in public places is violating the laws”.

The UAE’s prohibition on cross-dressing was also listed in a “code of conduct” for tourists issued by the Abu Dhabi tourist police (in 12 languages) in 2012. A few years earlier Dubai police had arrested 40 “cross-dressing tourists” of unspecified nationality. It is unclear what happened to them.

Press reports from the Emirates show a variety of cases since the crackdown on cross-dressing began:

-

A 45-year-old Indian man was convicted of cross-dressing and using mascara at the Mall of the Emirates in Dubai. The man, a manager with a property firm who also worked in the film industry, claimed he was rehearsing for a Bollywood film role which required him to dress as a woman.

The man was given a six-month suspended jail sentence and fined Dh10,000 ($2,700). A report in Gulf News said: “The judge suspended his imprisonment because it's his first offence and it [is] believed that he won't repeat the crime.”

-

A 22-year-old Emirati student was convicted of “consensual homosexual sex, cross-dressing and insulting a religious item or creed”. He was arrested at Dubai airport on his way to Europe in the company of his partner, an Emirati man who had previously been convicted of homosexuality. Prosecutors said the student featured in pornographic material found on his laptop. A report in The National said:

“Public Prosecution records state that ‘the suspect has circulated materials which defy decency by posing in a provocative manner using women's make-up in his underwear and at times in swimsuits revealing his buttocks, and, at times, wearing female clothes and accessories’.

“He was also convicted of insulting a religious creed or item after prosecutors said that he circulated images on the net of himself dressing up in a 'hijab' while reading the Holy Quran. ‘He has insulted the Islamic creed by wearing female make-up, accessories and a hijab-like veil while sitting in front of the Holy Quran and acting like he is praying,’ the indictment sheet said.”

He was initially sentenced to three years in jail but this was reduced to one year on appeal.

-

A 30-year-old Egyptian man was acquitted of cross-dressing in Dubai International City. Police claimed he had been wearing a bra and panties – which the man denied, saying they were in a bag that he had found outside his house.

He told the judge: "I swear to God that I am not a pervert … your honour, I was born a man and am proud of my masculinity. I do not mind undergoing any biological test to prove my manliness, if that is what it takes to convince the court that I am a normal adult."

Dubai Misdemeanours Court decided there was not enough evidence to convict the man. Prosecutors later appealed against his acquittal and the appeal court’s decision appears not to have been reported.

-

A beautician from the Philippines was sentenced to two years’ jail, followed by deportation, after being convicted in Dubai of “cross dressing, pretending to be a woman, tricking a woman into undressing in front of him, assault and practising medicine without the proper permits”. There are indications from the press reports that the person was transgendered rather than just a cross-dresser.

The case came to light after a female inspector, posing as a customer, visited the beauty salon. According to The National, the inspector assumed the beautician was a woman “as he had long hair, wore women's clothes, perfume and make up, and had manicured hands. He had also been taking breast enlargement tablets”.

Following the undercover visit, the inspector reported the salon to the police for various breaches of the regulations, and the police arrested the beautician. According to another report, “one of the beautician's fellow employees told the officers of his true gender”.

Police photo of man arrested for "violating public decency"

-

An Indian man (above) was arrested for "violating public decency" after being found in a “women only” park in Sharjah wearing a black abaya. He was reported by a woman who noticed his moustache.

-

A Filipino man was arrested at a shopping mall in Abu Dhabi, allegedly dressed in women’s clothes and holding a handbag.

A report in The National said: “Store workers were making fun of him when one took offence and called the police. When officers arrived, the Filipino denied being dressed as a woman. Police then searched his bag and found make-up.”

It’s notable that these cross-dressing cases targeted men, or possible trans women, rather than boyat. In its report on Kuwait, Human Rights Watch commented that boyat tended to be arrested “for crimes such as public disturbances or aggression, rather than for imitating a member of the opposite sex” and the same may have applied in the Emirates. This would be consistent with a press report in the UAE which portrayed boyat as female bullies operating in gangs who preyed on other girls and even threatened to rape them. "Sometimes their self esteem comes from being predators by being really strong like males,” a professor of psychology was quoted as saying.

Government campaigns against gender “transgression” also give legitimacy to action by individuals and organised vigilantes. The most notorious example of this was Iraq where militias held sway in many parts of the country after the overthrow of Saddam Hussein. Although men suspected of being gay were often the target, enforcement of gender stereotypes seemed to be at least as important a factor. The most trivial details of appearance, such as the length of a man's hair or the fit of his clothes, could determine whether he lived or died.

“Murders are committed with impunity, admonitory in intent, with corpses dumped in garbage or hung as warnings on the street. The killers invade the privacy of homes, abducting sons or brothers, leaving their mutilated bodies in the neighbourhood the next day,” Human Rights Watch said in a report issued in 2009. The campaign was thought to have begun in Sadr City, the Mahdi Army's stronghold in Baghdad, but also spread to Kirkuk, Najaf and Basra.

The militia killings tapped into social anxieties about "traditional" values and cultural change, HRW said. “These fears, springing up in the daily press as well as in Friday sermons, centre around gender – particularly the idea that men are becoming less ‘manly’, failing tests of customary masculinity.”

Challenging the norms

There is no doubt that transgender people, and others in the Middle East who visibly challenge gender norms, have touched a raw nerve. Researcher Rasha Moumneh views this in the broader context of social change:

“As women in the Gulf become more visible, both socially and politically, and as migrants bring with them different ways of living, the region's governments are stepping up their gender policing. To allay fears among conservative elements, they are regulating more tightly what is deemed acceptable behaviour for men and women …

“In times of social strain, gender and sexuality often become the focal point of broader anxieties, a phenomenon evident in media frenzies, new proposed legislation, and the brutality of the police and the impunity with which they act against an already vulnerable population.”

Historically, Muslims in various parts of the world have dressed in a variety of ways. In the old days, communities were fairly isolated. This allowed each to have its own distinct customs and traditions. Within each community, though, people would tend to dress similarly, for reasons of practicality rather than religious dogma; they would wear whatever was available locally, and choice was limited. There might be the odd eccentric who dressed differently, but they could be tolerated because no one seriously considered them a threat to the "Islamic" way of life.

Since then, television, foreign travel and the like have brought increased contact, not only between different Islamic traditions, but between different cultures. Young people pick up fashion trends from elsewhere and experiment with them, while more conservative folk – usually the literal-minded religious sort who believe anyone who disagrees with them will end up in hell – are appalled at what they see and feel threatened by the disregard for their authority.

Parallel with this is an international situation where many in the Middle East – rightly or wrongly – feel they are under siege from the west and respond to it, as a form of self-defence, by asserting supposedly traditional "Islamic values". In reality, some of these values may not be as traditional as people imagine but they tend to be highly visible, and strict enforcement of male and female codes of behaviour and dress is one of them.

Viewed in that light, adherence to the codes becomes the sartorial equivalent of patriotic flag-waving, and anyone who doesn't conform is regarded as betraying the cause. The rules promulgated by “traditionalists” today are a far cry from what was originally a simple injunction on Muslims to assume a modest appearance. In extreme cases, they also reflect an extraordinarily superficial approach to religion where there's more concern over a man who is "improperly" dressed than a one who takes bribes at work and beats his wife at home.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed