Suppose for a moment that Islam had not become the dominant faith in the Middle East and that instead most of its people were Mandaeans or Yazidis, Zoroastrians, Samaritans, Copts, Kalashas or Druze.

Had it happened, the Middle East would be a somewhat different place, both politically and culturally. The food might be vegetarian rather than halal, in place of the hijab there might be a taboo on wearing blue clothes, men might have long moustaches instead of salafi-style beards, or peacocks might be more revered than the prophet Muhammad.

It didn't happen, of course, and was never very likely to happen – partly because of the route that history took but also because these minority faiths were less inclined than Islam towards proselytising or conquest, or perhaps less successful at it.

Most of them pre-date Islam but today their future is uncertain and their very survival is in question. Even in the Middle East little is known about them – one reason being that they are often secretive about their beliefs which in some cases are known only to the priesthood and concealed from ordinary followers. Inevitably this can give rise to misunderstandings and unwarranted prejudices among outsiders, such as the oft-repeated claim that Yazidis are devil-worshippers.

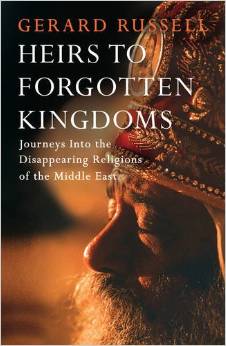

In a new book – "Heirs to Forgotten Kingdoms: Journeys into the Disappearing Religions of the Middle East" – Gerard Russell provides insights into seven of the region's minority faiths, and the current sectarian turmoil makes it especially timely.

In Russell's hands, what might have been a rather dry exposition of different faiths has turned into something much more lively and revealing. He has journeyed – often with some difficulty – to meet their living members, both followers and leaders. The result is a kind of travelogue, written with elegance and erudition, which helps to place them in a contemporary context.

Few people are as well-placed as Russell to do this. He's a former British diplomat who knows the region and is fluent in Arabic and Farsi. In the early 2000s he headed a special Foreign Office unit responsible for communications with Arabic-language media.

One recurrent theme of the book is the eclectic nature of religions: how they adopt and adapt ideas, sometimes from faiths which have now vanished. The Mandaeans, centred in southern Iraq, were mistaken for Christians by early missionaries because they worship one god and practise baptism – a tradition they actually acquired not from Jesus but from John the Baptist.

Mandaean rituals, Russell writes, "connect the present day with the distant pre-Christian past, the funerary banquet of the Mithraists and the Egyptians, and the teachings of the Manichees, the now extinct religion that in its day had followers as far away as China and competed with Christianity for the loyalty of St Augustine."

The Druze, meanwhile, have been influenced in part by the Greek philosopher Pythagoras whose right-angled 3:4:5 triangle apparently has more than mathematical significance.

At a time when Islamists vie with each other to impose the strictest behavioural codes, the Druze have a refreshingly take-it-or-leave-it attitude: you can pray if and when you feel like doing so, and a popular Druze meal is pork cooked in wine – a doubly sinful dish in the eyes of orthodox Muslims.

This easygoing approach applies only to the lay folk who don't need to trouble themselves much with theology; Druze clergy, however, who account for about 15 per cent of the community and include women as well as men, lead much more austere lives.

As with some other sects in the region, Druze beliefs are mysterious, though the Druze prefer to describe them as "private" rather than "secret". Hoping to discover more, Russell pays a visit to Walid Jumblatt, the political leader of the Druze in Lebanon. Jumblatt unhelpfully tells him "I know nothing about the Druze" but presents him with a gift: a couple of books by the British leftist (and atheist) Tariq Ali.

In his meetings with others, Russell enquires about the Druze doctrine of taqammus, an Arabic word which has connotations of changing one's shirt. This is an oblique way of referring to transmigration of souls – the idea that when a person dies the soul immediately finds another body to inhabit.

In theory Druze souls never leave the Druze community, which raises the question of what happens if there are not enough spare bodies to receive them. The answer given by popular mythology, Russell says, is that they go to China.

There's another sense, too, in which souls are migrating. Discussing his book in a podcast for History Today, Russell says:

"It's rather like looking at a coral reef that's dying, and you can see large patches of it that are no longer as diverse as they were. That's true of the Middle East as well, not only its physical heritage but also the ideas and the living traditions represented by these communities are under grave threat.

"It's not just the threat of war which they have lived through and survived before but it's the opportunity to leave which they have never had before, which means that great numbers of them – 90% of the Mandaeans of Iraq, two-thirds of the Christians in Iraq – in the last 20 years have gone."

Russell's tour of Middle Eastern faiths ends on the other side of the Atlantic where he encounters a Mandaean woman in a Detroit supermarket – one of a growing number of exiles in the United States. They tend to live in tightly-knit communities centred around their places of worship and members who were not particularly religious in their homeland often become more religious on moving to the United States, apparently as a way of preserving their culture and traditions. But the other side of this is that their original communities in the Middle East are becoming depleted and weakened.

Russell writes of these communities with the same passion that environmentalists show for endangered species. The diversity they reflect is something that Islamists in particular try hard to deny, and in the Middle East freedom of belief is not a widely accepted concept. That needs to be challenged as vigorously as possible; for as long as these faiths exist they are entitled to protection.

It is fascinating too, from a philosophical and historical point of view, to study their similarities and differences – an exercise which can also give some insight into the human psyche.

But Russell's book did leave me with some ambivalent feelings. While minority faiths contribute to the world's diversity, their own members don't necessarily benefit from it. On the whole, religions are not something that people choose after carefully considering all the options but something they are born into and stay with. That is especially true of the Middle East and where minority faiths need to construct a protective shell around themselves the effect, very often, is to narrow people's horizons rather than broadening them.

In Lebanon, Russell describes meeting Hassan, a Druze whose wife was a member of the clergy:

"Just as the male sheikhs tilled the land, she and other women sheikhas worked on embroidery and other home crafts that allowed them to earn an income without going out into the world. If Hassan’s wife did go outside her home, she would wear a white handkerchief on her head and half covering her face ...

"Hassan was not a talkative man, but he was beginning to open up. Where had he been in Lebanon? I asked. ‘Down to Beirut and back here.’ He had never left the Druze areas; his whole world, I guessed, could be no more than a square fifteen miles on each side."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed