For the last two years a Saudi-led coalition has been waging a war in Yemen to restore the "legitimate" government headed by Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi. But that goal is now in doubt because Hadi's lacklustre performance has opened up a rift between Saudi Arabia and its key ally in the conflict, the United Arab Emirates.

Hadi is officially recognised by the United Nations as Yemen's legitimate president though his legitimacy, which was never strong, has become increasingly questionable.

In 2012, after months of street protests, Ali Abdullah Saleh – who had ruled for 34 years – was persuaded (very reluctantly) to step down from the presidency. Under a plan developed by the GCC states, Hadi – who had served as Saleh's deputy and had no significant power base of his own – was installed as Yemen's "transitional" president.

Hadi's position was then confirmed, after a fashion, in a single-candidate "election" – even though the Yemeni constitution clearly stated there must be more than one candidate.

This irregularity, which had backing from the UN and western powers, was ignored at the time because Hadi was supposed to be only a temporary president. He was "elected" to oversee a two-year transition process, after which a new presidential election would be held. In the event, though, the transition process collapsed and no fresh election took place.

In 2014, Houthi rebels from the far north of Yemen over-ran the capital, Sanaa, with support from ex-president Saleh. Hadi fled to the southern city of Aden and later to Saudi Arabia as the Houthi/Saleh alliance rapidly extended its control to other parts of the country. This prompted the Saudi-led military intervention which began a few months later.

The Houthis, of course, have no constitutional legitimacy but in the areas they control, despite the hardships, they appear to have substantial public support – support which probably owes more to the unpopularity of the Saudis and their bombing campaign than the popularity of the Houthis themselves.

In the "liberated" areas of the south, however, divisions are more apparent. One fragmentation line is between those who want a united Yemen (assuming the Houthis are eventually defeated) and those who want a separate state in the south. Another is between protégés of Saudi Arabia and protégés of the UAE.

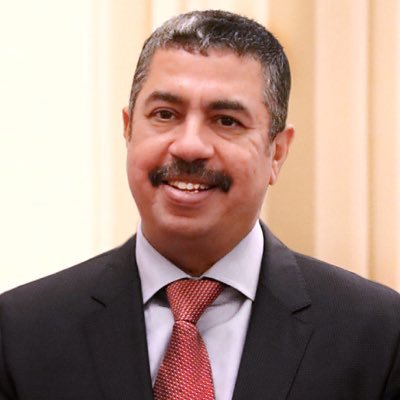

There have been signs of Saudi-Emirati friction for some time. Hadi is seen as firmly in the Saudi camp and last year when he abruptly dismissed his prime minister, Khaled Bahah – ostensibly in a dispute about ministerial appointments – there were claims that the real reason was Bahah's Emirati connections.

Differences of opinion among allies are not uncommon but efforts are usually made to keep them low-key and, preferably, private. Between the Saudi-backed and Emirati-backed elements in Yemen, however, the disagreements are increasingly obvious and it's difficult to see how they might be resolved.

In February there was a tussle over Aden airport. Forces commanded by Colonel Saleh al-Amiri Abu Qahtan (and reputedly paid by the Emiratis) had been protecting the airport since 2015 but Hadi wanted them to hand over control to the presidential protection forces commanded by his son, Nasser.

The colonel's response was to close the airport shortly before Hadi was due to land on a flight from Riyadh, and his plane was diverted to the island of Socotra.

According to the website Rai al-Youm, Hadi later flew to the Emirates to complain but was given short shrift:

President Hadi received a number of shocks starting with his plane’s landing on the Abu Dhabi International Airport where the only person who was there to receive “the president” was Maj Gen Mohammad Hamad al-Shamesi, the head of the UAE intelligence apparatus. This constituted a clear message: “This is your stature and weight in the UAE and you mustn’t expect more. You are just a Yemeni security file for us.”

There are conflicting pieces of news regarding the visit of President Hadi to Abu Dhabi. Some indicate that he left two hours following his arrival to object to the nature and type of the reception, while others say that he waited for a few hours at his hotel with the hope of meeting with Sheikh Mohammad Bin Zayed, and when he was told that the man was “busy” with other things, he angrily rushed to the airport and deemed this a non-acceptable insult.

The situation escalated further at the end of April when Hadi dismissed and replaced the governor of Aden along with four ministers who were regarded as affiliates of the UAE – triggering protest demonstrations.

Since then, two senior Emirati figures have publicly expressed dissatisfaction with Hadi. Anwar Gargash, the UAE's minister of state for foreign affairs, posted a tweet saying:

"Among the rules of political action is that you should build trust with your allies, that you should not stab them in the back, that your decisions should be commensurate with your capabilities and that you put public interest ahead of personal ones."

Dhahi Khalfan Tamim, Dubai's head of security, also tweeted:

"Replacing Hadi is a Gulf, Arab and international demand."

and ...

"The first steps towards a solution in Yemen would be to end Hadi's reign, which has eroded with time."

Politically, however, getting rid of Hadi would be extremely tricky. Slender as Hadi's legitimacy may be, any replacement would have even less. In the current circumstances there's no prospect of holding an election and there would still be questions about whether his successor's loyalties lay more with the Saudis or the Emiratis.

An even bigger question is how these Saudi-Emirati machinations will affect Yemen's long-term future. While the Saudis continue bombing in the north, the Emiratis have been working more quietly, but with limited success so far, to establish a semblance of order in the south. Over time, this could have the effect of creating a de facto partition of Yemen – which, whether or not the Emiratis intend it, is exactly what the southern separatists want.

In a book due to be published later this month, Yemen expert Ginny Hill writes:

Riyadh might wish to play the winning hand but the decisive cards could well be in the hands of the Emiratis. By deploying special forces to Aden in 2015 (and later, during 2016, in Mukalla), the Emiratis have already shaped the facts on the ground, and as a result of their outreach to grassroots groups across the south, they have also established significant ties with local powerbrokers, including southern separatist groups. Depending on the future stance taken by the Emiratis in relation to southern independence, Yemen’s recent experiment in unification could yet turn out to be an aberration in the country’s long and intricate history.

Aside from the negative effects of partition on Yemen’s already shattered economy, creating a separate state in the south would also create a separate state in the north – one which is currently under the control of the Houthis. In other words, it could allow the Houthis to consolidate their position and present the Saudis with a hostile state permanently on their southern border.

But whether the Emiratis can ever stabilise the south is still an open question, as a recent report in the Economist explained:

The Emiratis have attempted to give [Aden] a facelift, but while schoolgirls welcome their new computers and freshly painted classrooms, they worry about getting to school safely: kidnappings, night-time gunfire and explosions cause their trepidation. The presidential palace should be Aden’s safest place, not its most frightening, says Kholoud Mousa, a 19-year-old whose school lies below.

Southern secessionists maintain what order there is. Young men bristling with guns careen in pickups along pavements. Some officials now feel confident enough to move around Aden without bodyguards. But although the South Yemen flag is more common, al-Qaeda’s ensign also appears on alley walls. Soon after the Emiratis restored Aden’s national library, extremists blew it up ...

Thousands of fighters they have trained have gone AWOL (after collecting their pay). Motivating recruits to push north is an uphill task even with the payment of bonuses. Those who were happy to fight for their own homes seem unenthused about fighting for somebody else’s.

The Emiratis, the Economist continued, "are beginning to tire of their bickering wards". But now that they are in Yemen pulling out could make things worse:

"Officials who hoped that Aden would be a model for the rest of Yemen now fear that leaving the south on autopilot might only condemn the country to instability. And that might engulf the whole Arabian peninsula."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed