Do news organisations have a duty to publish stories from anonymous sources when there is reason to believe they are untrue? Apparently some people think so.

Yesterday, following scientific tests, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons confirmed that inhabitants of Khan Sheikoun, in the Syrian province of Idlib, had been "exposed to Sarin, a chemical weapon", during an attack last April. Reports at the time said at least 74 died and hundreds were injured.

The news that Sarin had definitely been involved caused a buzz on Twitter from people refusing to believe it. Many pointed instead to an article in a German newspaper last weekend which quoted an unnamed "senior adviser to the American intelligence community" as saying no chemical attack had taken place.

The article, by veteran American journalist Seymour Hersh, suggested that Syrian forces using a conventional explosive bomb had accidentally hit a store of "fertilisers, disinfectants and other goods" causing "effects similar to those of sarin".

Hersh's version contradicted evidence from a range of sources and, in the light of yesterday's announcement from the OPCW, is clearly untrue. As far as some people were concerned, though, it said what they wanted to hear and, even after the OPCW reported its findings, they were still complaining that mainstream media had failed to take Hersh's ridiculous story seriously.

An article on The Canary Website began:

"An acclaimed investigative journalist [Hersh] has now blown a giant hole in the official narrative of one of 2017's most explosive world events: the Syrian 'chemical attack' and Donald Trump’s fierce response. But the BBC and other media outlets seem to be completely ignoring his exposé."

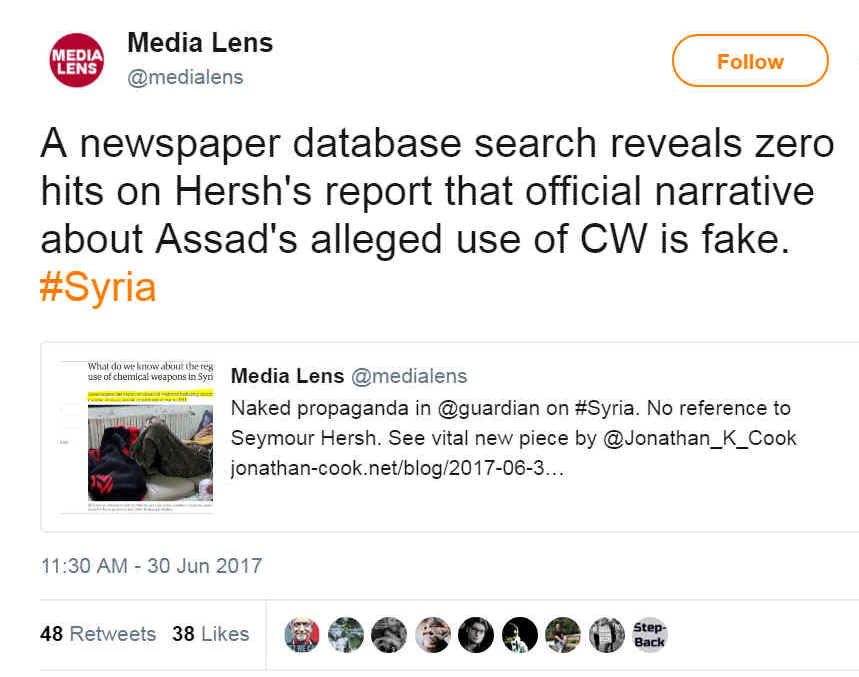

Media Lens, an organisation dedicated to "correcting for the distorted vision of the corporate media" grumbled that searching a database of newspapers had revealed no mentions of Hersh's article.

Meanwhile Jonathan Cook, a journalist who mainly reports on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, wrote in a blog post:

"If you wish to understand the degree to which a supposedly free western media are constructing a world of half-truths and deceptions to manipulate their audiences, keeping us uninformed and docile, then there could hardly be a better case study than their treatment of Pulitzer prize-winning investigative journalist Seymour Hersh.

"All of these highly competitive, for-profit, scoop-seeking media outlets separately took identical decisions: first to reject Hersh’s latest investigative report, and then to studiously ignore it once it was published in Germany last Sunday. They have continued to maintain an absolute radio silence on his revelations ..."

But why should anyone pay attention to Hersh when an anonymous source tells him something that flies in the face of evidence? The reason, apparently, is that he won a Pulitzer prize for journalism 47 years ago. His supporters constantly mention the Pulitzer as if that's a good reason for unquestioning faith in whatever he writes.

Winning a Pulitzer obviously means a reporter's work has impressed the judges but it's not necessarily a guarantee of factual accuracy. In 1981, one of the winners was a Washington Post journalist whose story about an eight-year-old heroin addict later turned out to be fabricated.

Hersh has certainly done valuable reporting in the past. He exposed the Mai Lai massacre in Vietnam back in 1969 and, more recently, the horrors of Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Some of his other exposés have misfired, though, and he has often been criticised for his use of shadowy sources. In the words of one Pentagon spokesman, Brian Whitman, he has "a solid and well-earned reputation for making dramatic assertions based on thinly sourced, unverifiable anonymous sources".

Another complaint about his more recent work is that he spends too much time listening to his unidentified sources and not enough looking at open-source evidence which points in a different direction. In an earlier article where Hersh suggested the Assad regime had not been responsible for Sarin attacks near Damascus in 2013, he either overlooked or disregarded evidence which didn't fit his argument and posed a number of questions which other writers had already answered.

His 2013 article about chemical weapons in Syria was rejected by the New Yorker magazine and eventually published in Britain by the London Review of Books. However, the London Review of Books rejected his latest article – which is why it ended up being published in Germany.

Inevitably, Hersh's loyal supporters discount the most likely reason for these rejections – that his editors found the articles flaky – in favour of a media conspiracy. Jonathan Cook (this time writing for Counterpunch) says:

"Paradoxically, over the past decade, as social media has created a more democratic platform for information dissemination, the corporate media has grown ever more fearful of a truly independent figure like Hersh. The potential reach of his stories could now be enormously magnified by social media. As a result, he has been increasingly marginalised and his work denigrated. By denying him the credibility of a 'respectable' mainstream platform, he can be dismissed for the first time in his career as a crank and charlatan. A purveyor of fake news."

This may explain why Media Lens, which specialises in critiquing the mainstream media, has such a high opinion of Hersh.

Media Lens has previously taken a dim view of journalists who use anonymous sources. A few years ago it bombarded the Guardian with complaints over a news story about Iraq which extensively quoted unnamed American officials. These sources, Media Lens said, were used "with no scrutiny, no balance, no counter-evidence – nothing".

Exactly the same charges can be levelled against Hersh but Media Lens not only seems unperturbed but is urging other media to regurgitate his anonymously-sourced story.

To some extent, scepticism about chemical weapons in Syria is a knee-jerk reaction to misleading reports about Iraq's imaginary weapons of mass destruction in the run-up to the 2003 invasion: if we were deceived over Iraq, how do we know we are not being deceived over Syria?

The best protection against that – then, as now – is evidence. Regardless of who is claiming what, check for evidence that might support their claims.

In Syria there is abundant evidence that Sarin has been used as a weapon during the conflict. The Assad regime, by its own admission, had stockpiles of Sarin – and possibly still has some. It also denies that any has been lost, stolen or captured. Furthermore, there is no evidence that rebel groups fighting in Syria have ever possessed or had access to Sarin. Draw your own conclusions.

In Iraq, on the other hand, suspicions about Saddam Hussein's weapons were not supported by evidence. During the long build-up to war, constantly repeated claims from politicians and others led many prominent journalists to abandon their critical faculties. But, as with Hersh's Syria articles, warning signs were there if only people looked for them.

The Washington Post, for example, devoted an extraordinary 1,800 words to an extremely flimsy (but scary) story suggesting Iraq had supplied nerve gas to al-Qaida.

At the New York Times, star reporter Judith Miller was churning out more alarmist stuff. One story concerned US attempts to stop Iraq importing atropine, a drug used for treating heart patients which is also an antidote against pesticide poisoning ... and nerve gas. This tale, as presented by Miller (with assistance from anonymous official sources) was that Iraq not only possessed nerve gas but intended to use it and wanted to protect its own troops from the harmful effects.

Another of Miller's "scoops" was an unverified claim that a Russian scientist, who once had access to the Soviet Union's entire collection of 120 strains of smallpox, might have visited Iraq in 1990 and might have provided the Iraqis with a version of the virus that could be resistant to vaccines and could be more easily transmitted as a biological weapon.

Unfortunately, there were plenty who took her word for it at the time. She was, after all, a Pulitzer prize-winning investigative journalist.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed