|

Lebanon is due to start a two-week lockdown on Friday amid a sharp rise in coronavirus infections, though there are doubts about how widely it will be observed or enforced.

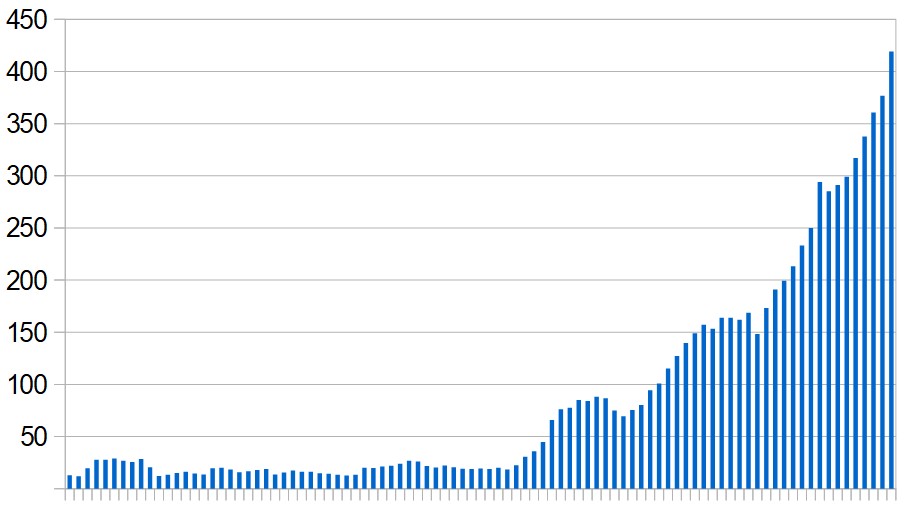

The Lebanese outbreak is still relatively small, with 10,347 cases confirmed since it began in February but more than half of those have been diagnosed since the beginning of this month. New cases averaged more than 400 a day during the past week – double the level before the devastating explosion in Beirut on August 4. Yesterday, 589 new cases were reported – the highest daily total so far.

Many of Beirut's health facilities were damaged in the blast and are now under severe strain due to the combined effects of the virus and injuries from the explosion.

Covid-19 infections were already rising before the explosion – a situation that President Michel Aoun blamed on “people’s disregard for the preventive measures”. Towards the end of July the authorities declared two five-day lockdowns separated by a two-day reopening but the second lockdown was largely forgotten in the aftermath of the explosion.

The new two-week lockdown means private businesses, including markets, shopping malls, gyms and swimming pools, have to close and there will be a 12-hour night curfew starting at 6pm each day.

However, there are plenty of exceptions. Clear-up and relief work in connection with the explosion will be allowed to continue and Beirut airport will remain open.

Given the political and economic turmoil in Lebanon it's unlikely the lockdown will achieve very much. The authorities have so far shown little inclination to make it effective and the public have plenty of other problems to worry about.

Quoted in the Daily Star newspaper, Dr Firass Abiad, head of the Rafik Hariri University Hospital in Beirut, said:

“Let’s be clear that this is a partial lockdown. It is clear they didn’t want to cripple whatever is left of the economy; they wanted to give people the opportunity to fix their homes [after the blast], and to be able to go out and buy groceries.

“If we want to give this loose lockdown a chance to work, people have to do their part ... otherwise nobody should be surprised at the end of these two weeks to find ourselves back where we started.”

At a news conference this week cardiologist Assem Araji, who heads the parliament's health committee, accused the interior ministry of failing to enforce the preventive measures decreed by other ministries. “Whether it was weddings or funerals, in supermarkets and all gathering places, there was no commitment,” he said. People who were supposed to be in quarantine had also been allowed to mix with others.

One aim of the lockdown is to relieve the pressure on hospitals. Six major hospitals and 20 clinics sustained damage in the Beirut explosion and on Monday caretaker health minister Hamad Hassan warned that medical services were "on the brink".

“Public and private hospitals in the capital in particular have a very limited capacity, whether in terms of beds in intensive care units or respirators,” he told a news conference.

Further information:

RSS Feed

RSS Feed