by TREVOR H. J. MARCHAND

Dr Marchand is lecturer in the Department of Anthropology, School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. He is the author of ‘Minaret Building and Apprenticeship in Yemen’ (Curzon Press, 2001) which was the subject of his talk to a joint meeting of the British- Yemeni Society and the Society for Arabian Studies on 9 November 2001.

My concentration was disrupted. ‘What are you looking at?’, the man asked with detectable suspicion in his voice. He had come up beside me unnoticed as I stood staring upwards, my attention absorbed in the activities of several builders labouring precariously at the top of a new minaret tower. ‘Who are you working for?’, he continued. He was an elderly man, with a distinguished greying goatee, and sharp, dark eyes. ‘No one’, I replied. ‘I’ve come to Sana’a to study traditional builders’. His face softened a little, and he gestured to me to follow him.

|

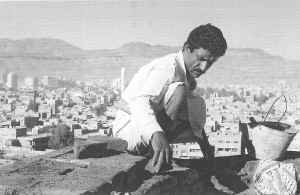

Mason Abdullah al-Samawi setting bricks at the top of the 'Addil Minaret. Picture: THJ Marchand |

We left the street to enter the forecourt of the mosque, and passed through the low doorway into the base of the free-standing minaret. Temporarily blinded in the darkness of the spiral stairwell, I groped the cool face of the curved outer wall with my right hand and climbed counter-clockwise along the uneven and debris-littered stairs, struggling all the while to keep pace with my interlocutor. I slowly grew accustomed to the dark, and intermittent slit windows enabled me to discern faces on the toiling bodies of labourers, strung-out along the winding staircase. They welcomed me as I passed, and some inquired anxiously where I was from, whether I spoke Arabic, and what was my religion. They amplified my brief and breathless responses with shouts that informed their work-mates on the stairs ahead about the nature of this foreign intruder.

The intensity of natural light grew stronger as we approached the top. In perfect form, my guide hopped from the last tread of the spiral staircase onto the perimeter edge of the tower’s circumference wall. He advanced several cat-like paces in the same counter-clockwise direction, then paused and glanced back at me with anticipation. I followed with carefully composed confidence, suddenly finding myself astride a circular brick wall, sixty centimetres thick, with a drop into the stair-shaft on my left and a thirty-five metre drop on my right. A steady breeze cooled my perspiration-soaked T-shirt as I stood there gazing at the horizons around us, spellbound by the views over sprawling Sana’a. It was incredibly exhilarating. Once again the master builder’s face softened, and this time with a broad grin of satisfaction. It was clear that I was at ease with these heights: apparently I had passed a test.

|

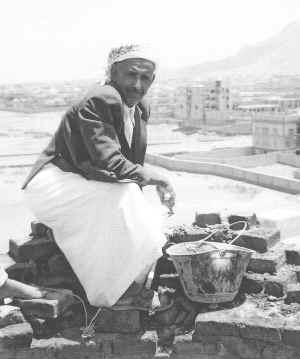

Muhammad al-Maswari, Chief Master Mason. Picture: THJ Marchand |

I was soon working for this renowned team of builders, and would remain in their service for the duration of my year-long field study. All the senior members were from the al-Maswari family, and Muhammad, the master mason who gave me my initiation, was their respected patriarch. These craftsmen were the sons and grandsons of the master builder (ustadh) Ali Sa’id al-Maswari, who died in 1986. He had come to Sana’a as a boy in the 1 930s from Maswar, a highland region west of the capital, and settled in the western suburb of Bir al-Azab where most of the family continue to live. Knowledge of the family genealogy prior to Au Sa’id is sparse. Unlike many of the sayyids and qadhis who have cultivated elaborate genealogies tracing their origins back through individuals to the founders of Islam, members of the middle classes, to which the al-Maswaris belong, trace their origins to particular ancestral places, or associate their ancestry with specific professional occupations. These al-Maswaris unquestionably constructed their identity around their engagement in the building trade, and they carefully fostered a region-wide reputation as excellent craftsmen.

Ali Sa’id, the family’s founding mason, began his career as a labourer working for several of the great master builders of his time, including Ustadh Aziz Mayyad and Ustadh Muhammad Muqbil Mayyad.

|

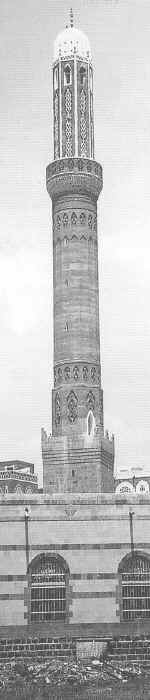

The refined skills and important social connections that he earned during his apprenticeship eventually resulted in his promotion to the rank of ustadh, and he was soon directing and managing his own commissions. He trained his sons, born of his first wife, and all four worked under his supervision, building residences and mosques, and, later, minarets. In 1980, while constructing the Husayni Mosque in one of the newer city quarters, Ali Sa’id was also commissioned to erect a free-standing minaret tower, the first such project undertaken by him and his sons. They derived stylistic inspiration and structural guidance from their observations of the city’s historic minarets, particularly the celebrated Musa Mosque built in 1747—8 AD and considered by experts and laymen alike to be quintessentially ‘Sana’ani’ in its style and proportioning. Between the completion of the Husayni minaret and the time of my study in 1996, the Bayt al-Maswari were responsible for the construction of some twenty-five minarets in and around Sana’a, successfully cornering this specialised niche market in the building trade. Undoubtedly, the skills of the Bayt al-Maswari combined with the patronage of their clients have been largely responsible for the renaissance of lofty minaret towers which pierce the skyline of the newer city quarters. With few exceptions, the funding for their commissions came from charitable trusts set up by prominent citizens of Sana’a, in some cases supplemented by grants from the Ministry of Awqaf. The choice of construction materials (i.e. kiln-baked brick or stone), stylistic details and the height of the towers was negotiated before the projects commenced, and was largely determined by the client’s financial resources, as well as by the builders’ aesthetic aim to achieve visually pleasing proportions. |

| The 'Addil Minaret, Sana'a, newly completed. Picture: THJ Marchand |

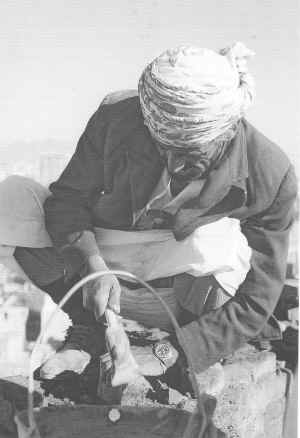

Design and the chewing of qat, an amphetamine-like stimulant, went hand-in-hand. Whenever I enquired about their creative processes, Yemeni craftsmen would cite the influence of qat. The master masons explained that design inspiration, especially for the complex patterns of decorative relief-style brickwork, came to them when they relaxed chewing qat in the evening.

Since Ali Sa’id’s death in 1986, Muhammad has commanded the team, assisted by his younger brother, Ahmad. The brothers each have a son actively involved in the family trade, and one of Ahmad’s grandsons represents the fourth generation of al-Maswari masons. A steady stream of contracts for prestigious projects has secured a comfortable middle class position for the family. Their relative affluence has enabled younger members of the Bayt to pursue a formal education, perhaps continue on to university, and to choose less physically demanding occupations which promise higher wages. A lack of interest shown by the younger generation has forced Muhammad and Ahmad to take on apprentices from outside the family, many of these coming from villages in the region of Dhamar, south of the capital. This has placed the brothers in a difficult predicament: Muhammad recognised that while striving to preserve and propagate his invaluable trade knowledge, he was engaged in a process which would undermine the basis of his family’s fame.

Muhammad was born in 1943, and five years later was enrolled in the al-Islah School. His formal education was brief, and by the age of nine he was working alongside his father on building sites. In time, his father began training him as an apprentice, and after acquiring a great deal of learning and practical experience, Muhammad was made his assistant, and eventually was elevated to ustadh in charge of his own projects. Along with some of the most prominent craftsmen at the time, he participated in building the Presidential Palace, and he can boast of having played an important part in reviving techniques of, and popular interest in, traditional architecture which was under siege from imported ideals of modernity and large influxes of capital following the Revolution. His achievements were officially recognised by the Council for the Preservation of the Old City of Sana’a (now the General Organisation for the Preservation of Historic Cities in Yemen), and in the footsteps of Ali Sa’id, Muhammad gradually achieved the status of a great master mason.

Builders like the al-Maswaris play an active role in the competing discourse between the so-called traditional and modernist schools of architecture. Late one morning, resting with the two master builders at the top of the minaret which we were constructing for the ‘Addil Mosque, I solicited their impressions of the new office towers being built in the city. Ahmad shrugged his shoulders and dismissed them as ‘no good’, and proceeded to sip his tea from a tin can. Muhammad turned his gaze towards the half-dozen or so concrete structures rising from Zubeiry Street and looming on the horizon to the southwest of us. He stared fixedly in their direction, remaining silent for a few moments before observing, ‘This (the minaret) will be here for a long time after they’ve crumbled and disappeared. Our construction is qawi jiddan (very strong) ... we use brick and stone, and we don’t need architects and their plans.’

Of the two senior brothers, Muhammad, in particular, kept a close eye on the younger masons, as well as on the rest of the work team, guiding their practices and correcting their mistakes when necessary. Through years of experience he had acquired an astonishing ability to accomplish his own tasks while simultaneously monitoring the progress of his fellow workers. Once, I watched him turn quickly, while continuing to lay bricks, towards the youngest ustadh, Abdullah al-Samawi, and inform him that the course-work he was laying around the wall of the stair-shaft did not conform to the correct radius. Accustomed to his mentor’s critical commentary, Abdullah didn’t take issue with Muhammad’s apparently off-hand judgement, but instead, with furrowed brow, he verified the curvature of his work with the radial rope attached to the metal post at the centre of the minaret. Muhammad had been right: the brickwork was leaning inwards by little more than a centimetre. Perfect alignment was not only an aesthetic hallmark of al-Maswari craftsmanship, but absolutely necessary if these towering edifices were to remain structurally stable.

In nearly all cases, a young builder remained under the tutelage of his seniors even after his responsibilities and wages had been augmented and his status as an ustadh had been confirmed by his master and recognised by his peers. In every practical sense, the teacher-student hierarchy of the apprenticeship persisted until the builder became the master of his own professional practice and secured his own clientele. There were numerous important skills to be acquired in addition to technical expertise. These included establishing and nurturing customer relations; estimating building costs and materials; managing physical and personal resources and, most important of all, gaining a seemingly intuitive knowledge of all phases of the design and construction process, from the smallest day-to-day details to envisaging the project as a whole. All of these, and the last in particular, required a great deal of time and a full immersion in all aspects of the trade. Ultimately, a mason became a true and recognised master when he moved beyond simply ‘understanding’ what needed to be done, and his actions and thoughts became entirely absorbed in the pursuit of responsible professional practice.

This expert level of absorption and concentration was apparent when observing Muhammad al-Maswari at work. Like a symphonic conductor, he was continuously aware of all members of his building team, monitoring their performance and bringing them back into line with his own standards and vision, when this proved necessary. His demanding demeanour was tempered by a composure and fairness of judgement which earned him a great deal of respect from those who worked for him. All his actions were precisely calculated, enabling him to move with great economy and grace, maintaining a regular and even tempo in the rhythm of his work. For example, when assembling the exterior facing of the walls of the minaret base, he meticulously set each cut stone in perfect position by repeatedly verifying its horizontal and vertical alignment with his simple level and plumb-line, gently tapping it into place with the dull end of his adze. He then proceeded to finger the oozing grout around every joint, almost caressing the face of the stone with his other hand, while eyeing it intensely to check its position in relation to the other stones in the course-work.

Muhammad’s approach to building materials seemed to transcend objective knowledge; he knew instinctively how to work with them, aware of their potential and limitations, not just generally, but of each individual brick and stone. Bricks of a certain quality were kept for carving, and others were relegated to the infill of walls; dressed stone was selected or rejected according to its colour, solidity, and grain. In Islamic Art and Spirituality (1987:56), Hossein Nasr observes that traditional Muslim craftsmen ‘had a profound sense of the nature of materials.., stone was always treated as stone and brick as brick’, and the materials were masterfully integrated ‘into a whole reflecting the ethos of Islamic art’. This characterised the work of Muhammad al-Maswari: his knowledge and craftsmanship transformed the ‘act’ of building into an ‘art’.

|

Ahmad al-Maswari, younger brother of Muhammad, carving a brick. Picture: THJ Marchand |

July 2002