Surprising as it might seem, both the Syrian government and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) agree that people were exposed to Sarin in Khan Sheikhoun last April.

This should now become the starting point for any rational discussion of what happened there. Following the latest results from chemical tests there is simply no point in anyone talking about hoaxes or claiming the deaths and injuries were caused by bombs hitting supplies of disinfectant or fertiliser.

Even a bomb hitting stores of Sarin would not cause the effects seen in Khan Sheikhoun. The only logical conclusion is that the Sarin detected in the town had been used as a weapon – in which case the main question yet to be finally resolved is who did it.

The 78-page report circulated by the OPCW this week describes the fact-finding team's investigation and the methodology used: the interviews with witnesses, the symptoms found on victims, the samples taken from their bodies and the incriminating chemical traces detected by laboratory analysis. Summarising its findings, the OPCW says:

"The analyses of the samples indicate not only the presence of sarin, but also other chemicals including potential impurities and breakdown products related to sarin, depending on the production route and the raw materials used.

"By reviewing, in conjunction, the evidence relating to autopsy records, biomedical specimens, hospital records, witness testimony, photographs and video supplied during interviews, and environmental samples, the FFM [Fact-Finding Mission] concludes that a significant number of people were exposed to sarin, of which a proportion died from that exposure."

There was one significant gap in the team's investigation, though. In the immediate aftermath of the attack they were unable to visit Khan Sheikhoun – a rebel-held town – to collect samples from the scene of the alleged attack or examine fragments from any munitions said to have been involved.

The report explains:

"Owing to such factors as security concerns in the region of the alleged incident, the time frame of events – whereby no permission was in place when the team initially deployed, which would have provided the best circumstances for evidence retrieval – and some casualties and other witnesses had been transferred to a neighbouring State Party, it was determined that the risk of a visit to the incident area would be prohibitive for the team."

It goes on to say that the longer it took to get to the site the less benefit there would be:

"The scientific and probative value of visiting the site diminishes over time, particularly if it is not possible to manage access to the site. Hence, the evidentiary value of samples taken close to the time of the allegation, supported by photographic and video evidence and in association with witness testimony, needs to be balanced against the evidentiary value of the FFM visiting the site some time later to collect its own samples."

However, an unlikely helper stepped in – in the shape of the Syrian government who told investigators that an unnamed "volunteer" from Khan Sheikhoun had provided them with samples. These included soil, fragments of metal, bone, and vegetation. According to the Syrian authorities, one of these soil samples and the metal fragments had come from the crater which locals say was the point where the chemical weapon struck. The other samples were said to have come from various spots in the surrounding area.

The Syrian authorities also provided OPCW investigators with a video showing the samples being collected.

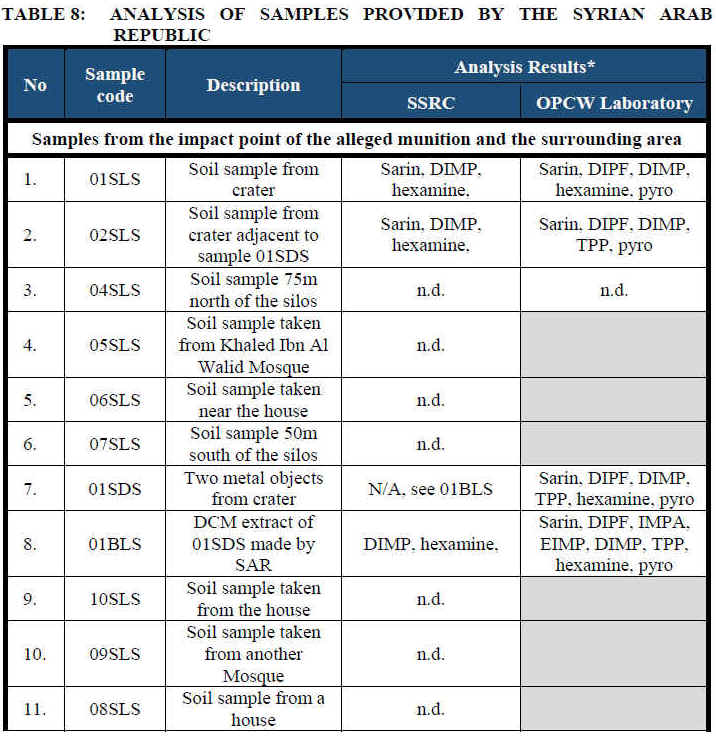

The samples were then split so that each could be tested separately by both the Syrian government's Scientific Studies and Research Centre and a laboratory designated by the OPCW.

The results of these two sets of tests were broadly the same.

The Syrians and the OPCW agreed that the soil from the crater and another sample from adjacent to the crater had tested positive for Sarin, DIMP (a by-product of Sarin production) and hexamine (used as an acid scavenger in Sarin made by the Syrian government). Additionally, the OPCW lab found evidence of other Sarin-linked chemicals.

The Syrians and the OPCW also agreed that extraction samples from metal objects in the crater tested positive for DIMP and hexamine. The OPCW lab additionally detected Sarin and other Sarin-linked chemicals.

Needless to say, the Syrian authorities are now pretending that this didn't happen. A statement from the foreign ministry in Damascus on Saturday dismissed the OPCW's report (and the Syrian government's contribution to it) as lacking "any credibility".

RSS Feed

RSS Feed