Syria chemical attacks: a question of sources

Blog post, 11 December 2013: My blog post yesterday about re-ignited debate over the chemical attacks in Syria last August has brought a surprising response from some regular critics of the mainstream media.

On one side of the chemical weapons debate is Seymour Hersh, the veteran investigative journalist, who suggested in an article for the London Review of Books that rebel fighters, rather than the Syrian regime, were to blame for the Damascus attacks.

On the other side is Eliot Higgins, better known as Brown Moses, whose dissection/demolition of Hersh's article appeared on the Foreign Policy website.

Behind this dispute about who caused the sarin deaths there is also a conflict between two different approaches to investigative journalism and the sources that they use.

Unlike Hersh, Higgins is not a traditional journalist. He spends much of his time researching the Syrian conflict via the internet, blogging and tweeting about it.

Unlike Higgins, Hersh has little time for the internet, relying instead on mysterious but apparently well-placed sources to construct his case.

Following my blog post yesterday, Media Lens entered the fray on Twitter, siding with Hersh (here and here). Media Lens is a British website that specialises in critiquing the mainstream media, which it regards as "a propaganda system for the elite interests that dominate modern society".

Its position, if I've understood it correctly, is that journalists working in the mainstream media gradually acquire a "corporate" mindset which makes them less willing to challenge authority.

Given that Hersh has spent decades working for mainstream media, that Media Lens disapproves of anonymous sources, and that it encourages "the creation of non-corporate media", logic might suggest that it would have sided with Higgins. But no.

Although Hersh writes for the mainstream media he's also a dissenting voice within it. He exposed the Mai Lai massacre in Vietnam back in 1969 and, more recently, the horrors of Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Some of his other exposes have misfired, though, and he has often been criticised for his use of shadowy sources. In the words of one Pentagon spokesman, he has "a solid and well-earned reputation for making dramatic assertions based on thinly sourced, unverifiable anonymous sources".

Higgins, meanwhile, is the antithesis of a "corporate" journalist but the problem seems to be that he is not challenging western governments' views of the chemical attacks in Syria. His assessment of the evidence is that it points strongly to the Assad regime being responsible and, as far as some are concerned, that's enough to place him in the "corporate media" camp.

The real issue, though, is not Hersh versus Higgins or corporate versus non-corporate. It's about methodology. Hersh represents the old methodology – closed, elitist and opaque – while Higgins reflects the new – open, egalitarian and transparent.

A rather telling illustration of this is that while Higgins's Foreign Policy article invites comments from readers, Hersh's article for the LRB does not.

Higgins relies on open sources (mainly YouTube videos of the Syrian conflict) and draws conclusions from them. Anyone who disputes his interpretation is able to challenge it and, based on the ensuing arguments and available evidence, people can form their own view as to where the truth lies. It's a collective process that often takes twists and turns, but it's thoroughly transparent: the evidence is there for everyone to see and contribute to if they wish.

One example of how this operates in practice came when UN weapons inspectors determined the trajectory of two of the rockets implicated in the August attacks. Tracing their flight path on a map, Human Rights Watch found that they intersected in the compound of the Republican Guard's 104th Brigade.

That suggested the Republican Guard could be responsible if both rockets had been fired from the same position (though it's not clear that they were).

Further discussion on the internet established that the rockets had probably not come from the Republican Guard's compound because their range was too short. Some interpreted this as exonerating the regime, though subsequent video analysis by Higgins seems to show there were other places, within range, that the Syrian military could have used to fire them.

In contrast to that, the Hersh approach is a display of journalistic virtuosity. It relies on developing special contacts – seemingly well-placed figures who are willing to spill the beans, usually anonymously.

Anonymous sources can be valuable at times (without them the Watergate scandal would never have emerged) but they have to be treated with care and a lot hinges on the credibility of the journalist reporting them.

With anonymous sources it's hard for readers to know why they agreed to talk and whether they have any axes to grind or scores to settle. That's a judgment the reporter should make, though when presented with a juicy quote it can be tempting not to probe too deeply.

One of the key reasons for blaming the Syrian regime for the August attacks is that it is known to possess sarin and also the munitions that were used to deliver it, while the rebels are not known to possess either.

Hersh disputes this in his article, asserting that "the Syrian army is not the only party in the country’s civil war with access to sarin", and that "American intelligence agencies produced a series of highly classified reports ... citing evidence that the al-Nusra Front, a jihadi group affiliated with al-Qaida, had mastered the mechanics of creating sarin and was capable of manufacturing it in quantity".

"Citing evidence that ..." is a tricky phrase that doesn't actually tell us much. It may simply mean that somewhere in a plethora of intelligence material someone was quoted as saying that al-Nusra knew how to make sarin. The fact that claims to this effect may be been cited in intelligence reports does not necessarily mean they were assessed as credible.

Indeed, Hersh later quotes a named spokesman for the US Office of the Director of National Intelligence as saying that no American intelligence agency "assesses that the al-Nusra Front has succeeded in developing a capacity to manufacture sarin".

Hersh's source on the supposed sarin-manufacturing capabilities is an unnamed "senior intelligence consultant":

"Already by late May, the senior intelligence consultant told me, the CIA had briefed the Obama administration on al-Nusra and its work with sarin, and had sent alarming reports that another Sunni fundamentalist group active in Syria, al-Qaida in Iraq (AQI), also understood the science of producing sarin ...

"An intelligence document issued in mid-summer dealt extensively with Ziyaad Tariq Ahmed, a chemical weapons expert formerly of the Iraqi military, who was said to have moved into Syria and to be operating in Eastern Ghouta.

"The consultant told me that Tariq had been identified 'as an al-Nusra guy with a track record of making mustard gas in Iraq and someone who is implicated in making and using sarin'."

Manufacturing sarin is a difficult and dangerous business, as chemical weapons expert Dan Kaszeta has frequently pointed out. No one has yet come up with a sensible explanation, or even a plausible theory, as to how al-Nusra could have produced it in the quantities required for the August attacks. Undeterred by that, Hersh clearly wants readers to accept the word of his "senior intelligence consultant". But how are readers to judge? Presumably by being assured that the source is not just any intelligence consultant but a "senior" one.

Interestingly, though, EAWorldView has an idea who this consultant might be. It notes that Michael Maloof, who formerly worked in the US Defense Department, has made very similar claims in an article for the right-wing World Net Daily, and also on the Russian propaganda channel, RT.

If so, it's rather odd that Maloof is saying things to Hersh anonymously that he has already said publicly. Writing on the Air Force Amazons blog, Kellie Strøm comments:

"Given his association with what are widely regarded as crude propaganda outlets, if Mr Maloof is Mr Hersh’s anonymous source then his anonymity would seem designed more to protect Mr Hersh’s reputation than Mr Maloof’s."

Sarin in Syria

Blog post, 14 December 2013: Following their investigation of the Sarin attacks that killed hundreds near Damascus on August 21, the UN inspectors have continued to look into other alleged cases of chemical weapons being used in the Syrian conflict. Their latest report, issued this week, confirms that people in Syria have been exposed to Sarin on other occasions – including government forces.

However, none of these other instances investigated by the UN caused deaths on the same scale as the August 21 attacks, nor do they appear to have involved the same type of munitions.

In contrast to the August 21 attacks, where the inspectors say there is "clear and convincing evidence" that chemical weapons were used against civilians "on a relatively large scale", their findings in relation to other instances are a lot more tentative.

There is no incident among these other cases where inspectors have been able to establish a definite link between the alleged event, the alleged site and the people affected by Sarin.

The UN investigation was triggered by complaints from various member states about 16 alleged chemical weapons attacks in Syria since October last year. Based on the reports it had received, the UN eliminated nine of these from its inquiry for lack of "sufficient or credible information", leaving six to be investigated (in addition to the attacks on August 21). These were:

-

Khan al-Asal (19 March 2013)

-

Sheikh Maqsood (13 April 2013)

-

Saraqeb (29 April 2013)

-

Bahhariyeh (22 August 2013)

-

Jobar (24 August 2013)

-

Ashrafiah Sahnaya (25 August 2013)

Under the terms eventually agreed with the Syrian government the inspectors were not allowed to apportion blame for any attacks and the latest report makes no attempt to do so.

The fact that a number of soldiers on the government side were affected by Sarin might suggest rebel fighters had access to chemical weapons as well as the Syrian regime, but on that point the report is far from conclusive. There could be other explanations, and if the rebels did have Sarin there’s no evidence that they possessed it in the quantities needed for the August 21 attacks or that they had the type of munitions used on August 21.

Khan al-Asal (19 March 2013)

This attack hit government-held territory in Aleppo province, reportedly causing at least 25 deaths. Although everyone seems to agree that a chemical weapon was used, most of the other facts are disputed. The Syrian regime, backed up by Russia which sent a lengthy report about it to the UN, insists it was a rebel attack. Others suggest it was a government attack that missed its target.

UN inspectors were unable to visit the site for security reasons, so their report does little to clarify the picture. They say they “collected credible information that corroborates the allegations” of chemical weapon use but could not verify this independently.

(There’s more discussion of this on the Brown Moses blog.)

Sheikh Maqsood (13 April 2013)

The US reported to the UN secretary-general that Syrian government forces had used a small amount of Sarin against the opposition in an attack on the Sheikh Maqsood district of Aleppo. According to witnesses, 21 people were affected and one died.

Efforts by the inspectors to failed to uncover further information. Consequently, the report says they were “unable to draw any conclusions”.

Saraqeb (29 April 2013)

A source close to the opposition claimed that a helicopter flying over Saraqeb had dropped items at three locations. One of these allegedly fell into the courtyard of a house where it “intoxicated” some of the family members.

A 52-year-old woman who had been severely affected was transported to Turkey where she died. The inspectors’ report says:

“During an autopsy that was observed by members of the United Nations Mission, samples of several organs from the deceased woman’s body were recovered for subsequent analysis. The results from most of these organs clearly indicated signatures of a previous Sarin exposure.”

Although inspectors were unable to visit the site, the report says collected evidence suggests that chemical weapons were used but “in the absence of primary information on the delivery system(s) and environmental samples collected and analysed under the chain of custody, the United Nations Mission could not establish the link between the alleged event, the alleged site and the deceased woman”.

The UN report also notes that this incident was “atypical for an event involving alleged use of chemical weapons”:

“The munitions allegedly used could hold only as little as 200 ml of a toxic chemical. Allegedly tear gas and chemical weapon munitions were used in parallel.

“The core of the device allegedly used was a cinder block (building material of cement) with round holes. These holes could, allegedly, serve to “secure” small hand grenades from exploding. As the cinder block hit the ground, the handles of the grenades would become activated and discharged. Some of the hand grenade–type munitions allegedly contained tear gas, whereas other grenades were filled with Sarin.”

(The Saraqeb incident is also discussed on the Brown Moses blog.)

The remaining three incidents in the investigation were all based on complaints from the Syrian government, at a time when it was blaming rebels for the August 21 attacks.

Bahhariyeh (22 August 2013)

A number of government soldiers engaged in fighting were reportedly taken ill when an object landed nearby and emitted “blue-coloured gas with a very bad odour”.

Blood samples collected by the Syrian government and the UN all tested negative for “any known signatures of chemical weapons”. The report therefore says the inspectors “cannot corroborate the allegation that chemical weapons were used”.

Jobar (24 August 2013)

The report says:

“Based on interviews conducted by the United Nations Mission with military commanders, soldiers, clinicians and nurses, it can be ascertained that … a group of soldiers were tasked to clear some buildings near the river in Jobar under the control of opposition forces.

“At around 1100 hours, the intensity of the shooting from the opposition subsided and the soldiers were under the impression that the other side was retreating. Approximately 10 meters away from some soldiers, an improvised explosive device reportedly detonated with a low noise, releasing a badly smelling gas.”

Ten soldiers were reportedly evacuated – four of them seriously affected.

UN inspectors visited the site but saw no value in collecting samples because the fragments of the alleged munitions had already been removed and the site had been corrupted by mine-clearing activities.

Blood samples taken by the Syrian government (and authenticated by the UN using DNA techniques) tested positive for signatures of Sarin. One of the four blood samples collected from the same patients by the UN a month later also tested positive for Sarin.

The report finds the collected evidence “consistent with the probable use of chemical weapons” but again adds that “in the absence of primary information on the delivery system(s) and environmental samples collected and analysed under the chain of custody, the United Nations Mission could not establish the link between the victims, the alleged event and the alleged site”.

Ashrafiah Sahnaya (25 August 2013)

According to the Syrian government, cylindrical canisters were fired at some soldiers, “using a weapon that resembled a catapult”.

Again, UN inspectors were not able to visit the site for security reasons but blood samples taken by the Syrian government and authenticated by the UN using DNA techniques tested positive for signatures of Sarin. Samples taken by the UN one week and one month after the alleged incident tested negative.

The report says collected evidence suggests that chemical weapons were used, though it is unable to “establish the link between the alleged event, the alleged site and the survivors”.

Questions for the Syria Sarin sceptics

Blog post, 16 December 2013: If Syrian government forces did not launch the chemical attacks near Damascus on August 21, we have to assume that rebel fighters did. Short of denying that the attacks took place at all, there is really no other possibility.

Although many people continue to dispute that the Assad regime was responsible, no one has yet come up with a plausible theory – let alone hard evidence – as to how the rebels might have done it.

The chemicals

We know the Syrian regime had plenty of Sarin as well as the type of rockets that were almost certainly used to deliver it in the August 21 attacks. In order to make a persuasive case that blames the rebels it would therefore be necessary to show that they too had access to Sarin in large enough quantities, as well as the relevant munitions.

As far as rebel Sarin is concerned there are three possibilities:

1. It was obtained from outside Syria

2. Rebels produced it themselves

3. It was stolen/captured from the Syrian regime's stockpile

The third possibility can be eliminated immediately because the regime has insisted throughout the conflict that its chemical weapons are secure and it has not reported any losses.

To advance an argument that Sarin came from outside Syria it would be necessary to identify possible suppliers: who was in a position to supply, and could they realistically have done so?

If the rebels made their own Sarin – a complex and dangerous process in itself – who did they manage to do so without detection and, apparently, without mishap? One might reasonably expect Syrian intelligence to have been on the lookout for this and eager to publicise any incriminating evidence they found. But apart from vague claims about chemical "factories" they have come up with nothing that clearly points to Sarin production by rebels.

The munitions

According to the Syrian regime, rebel fighters have used small quantities of Sarin on several occasions. One of these, allegedly, was in Khan al-Asal last March. The facts are disputed but the regime's version (cited in the latest report from UN weapons inspectors) is that rebels fired a chemical rocket from 5km away.

If this were true (and it may not be), the rocket cannot have been of the same type that was implicated in the August 21 attacks, since their probable range has now been established at a little more than 2km.

In the days following the August 21 attacks, the regime also accused rebels of attacking its soldiers on three occasions with canisters that emitted gas. The UN inspectors were unable to confirm this but, even if we accept the regime's version, the point to note is that the munitions allegedly used were fairly small. One is said to have had a capacity of four litres and one is said to have been launched from a catapult.

If we take the regime's claims at face value that still doesn't go very far towards convicting rebel fighters for the August 21 attacks. If we assume the rebels did use Sarin in these other incidents there's nothing to indicate they had enough of it for August 21, when it appears that hundreds of litres were used.

Also, the regime's claims about other usage of "rebel Sarin" do not link the rebels to the type of munitions implicated in the August 21 attacks.

In their report on the events of August 21, the UN inspectors stated:

-

"Impacted and exploded surface-to-surface rockets, capable to carry a chemical payload, were found to contain Sarin."

-

"Close to the rocket impact sites, in the area where patients were affected, the environment was found to be contaminated by Sarin."

The rockets concerned were of a type which is so far unknown outside Syria and which is known from video evidence to be used by the regime. There is no evidence, at least so far, of them being used by rebels.

To make a persuasive case against the rebels, therefore, it would be necessary to show how they could have acquired them, along with suitable launchers. Could they have captured them from regime forces? If that were what actually happened, why hasn't the regime said so?

Syria sarin attacks

Blog post, 5 March 2014: A report issued on Wednesday by the UN Human Rights Council came closer than any previous UN report to blaming the Syrian government for the chemical attacks near Damascus last August, as well as an earlier attack in Khan al-Assal.

While not directly accusing the Assad regime, the report says "the nature, quality and quantity of the agents used on 21 August [near Damascus] indicated that the perpetrators likely had access to the chemical weapons stockpile of the Syrian military, as well as the expertise and equipment necessary to manipulate safely [a] large amount of chemical agents".

The strong wording of this assessment suggests it is based, at least partly, on new information as result of the regime handing over its stockpile to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW). This would enable comparisons to be made between samples gathered by UN inspectors at the attack sites with chemicals now known to have been in the regime's possession.

Chemical weapons expert Dan Kaszeta has been pointing out for some time that hexamine was found in samples from the attack sites and that the Syrian government declared 80 tonnes of hexamine to the OPCW in its chemical weapons inventory.

Kaszeta, citing multiple sources, says the Syrian government has admitted using hexamine as an additive in sarin – an additive that is sufficiently unusual to suggest that the sarin used on August 21 came from the government's stockpile. Kaszeta maintains that hexamine is a "smoking gun" as far as responsibility for the attacks is concerned.

The latest UN report, if it's correct, poses serious difficulties for those who claim rebel fighters carried out the attacks – killing hundreds of people – as a "false flag" operation aimed at triggering western military intervention in Syria.

It virtually rules out the possibility that rebels made their own sarin or acquired it from any source other than the Syrian government – and the Syrian government has never reported losing any sarin or having any stolen. Even if the rebels did steal it they would, as the report points out, also need to have acquired the "expertise and equipment" to use it.

The UN report, which covers many other human rights violations in the Syrian conflict, goes on to say that chemical agents used in Khan al-Assal (in Aleppo province) "bore the same unique hallmarks" as those used in the August 21 attacks near Damascus. In other words, whoever was responsible for the Damascus attacks was also responsible for Khan al-Assal.

The Khan al-Assal attack hit government-held territory, reportedly causing at least 25 deaths, but most of the other facts are disputed. The Syrian regime, backed up by Russia which sent a lengthy but so far unpublished report about it to the UN, insists it was a rebel attack. Others suggest it was a government attack that missed its target.

In a report last December, UN inspectors said that although they were unable to visit the Khan al-Assal site for security reasons they had "collected credible information that corroborates the allegations" of chemical weapon use but could not verify this independently. Wednesday's report goes much further – implying that some new information has come to light regarding Khan al-Assal too. But it gives no clue as to what the "unique hallmarks" of that attack might be.

Wednesday's report also mentions other allegations of chemical weapons attacks but says they "displayed markedly different circumstances and took place on a significantly smaller scale".

Referring to the UN inspectors' investigations, it adds: "In no incident was the commission’s evidentiary threshold met with regard to the perpetrator." This is a very odd thing to say because there is no reason to believe that any threshold was ever set. The inspectors were prevented from apportioning blame under the terms of the agreement that allowed them into Syria.

Why chemical weapons in Syria must not be ignored

Blog post, 7 April 2017: One of the more effective examples of international cooperation has been the outlawing of chemical weapons. With just a few exceptions, the world has been remarkably successful in moving towards the completely eliminating them.

To date, only three countries – Egypt, North Korea and South Sudan – have neither signed nor ratified the Chemical Weapons Convention, plus Israel which has signed but have not ratified. Step-by-step work over the years has resulted in at least 80% of the world's known stockpiles of chemical weapons being destroyed, and efforts are continuing to destroy most of the rest.

Having got so close to eliminating them entirely, the world can't afford to let anyone start normalising their use. The importance of this should not be underestimated. In an article for the Huffington Post, Scott Gartner, a professor of international affairs, wrote:

"Chemical weapons prohibition works; this is not idealism run amok, the results are real ... If we can eradicate chemical weapons, we can save lives and avoid future military reactions and chemical-weapon-based red line-diplomacy."

Gartner was writing in 2013, shortly after the Assad regime had unleashed chemical weapons on a suburb of Damascus, killing hundreds of people. That attack brought calls for US military action. President Obama talked of limited action – "options that meet the narrow concern around chemical weapons" – but others wanted to treat it as a justification (or pretext) for wider American involvement in the war. I argued at the time that this would be a mistake and that the issues of chemical weapons and the broader conflict in Syria should be kept separate as much as possible:

"Although the chemical crisis has arisen out of the wider conflict, maintaining the international ban is a matter of global importance. Whatever people may think about the principle of intervening in another country's internal struggle, the use of banned weapons – wherever it happens – requires a strong international response."

In the event, Obama held back from military action, partly because he didn't have enough support in Congress. Instead, Syria became a party to the Chemical Weapons Convention and inspectors acting under UN auspices destroyed Syria's chemical stockpile and dismantled the production facilities (or so it seemed).

This has often been criticised as a "weak" response but it did reaffirm international norms regarding chemical weapons and avoided the unpredictable consequences of military options.

The problem now, though, is that the Assad regime reneged on the deal. In fact, it has been reneging for some time with the use of chlorine, which is not a chemical weapon per se but becomes one when used in warfare. Governments and media largely turned a blind eye to it but mass casualties in Khan Sheikhoun, apparently involving some kind of nerve agent, were difficult to ignore.

Trump's dramatic response – launching no fewer than 59 cruise missiles at the Syrian airbase apparently used for attacking Khan Sheikhoun – is in line with his instincts and also has the benefit of diverting attention from his problems at home. But it's still too early to know what it has achieved or what the consequences will be. Will it deter Assad from using chemical weapons again, or will he feel obliged to show that he has not been deterred?

Even if bombing of the airbase has the desired effect without introducing new complications there's still the issue of Syria's flouting of the Chemical Weapons Convention and the Assad regime's bad faith. As a matter of principle this ought to put Assad and his cronies beyond the pale where participation in any future political settlement is concerned.

Although the idea of Trump insisting Assad is not a fit and proper person to lead a country carries more than a little irony, this seems to be the position that Trump's regime is heading towards. Speaking yesterday, secretary of state Rex Tillerson described Assad's role in the future as uncertain: "With the acts that he has taken it would seem that there would be no role for him to govern the Syrian people." But Tillerson also seemed to recognise that excluding Assad from Syria's political future would need Russian cooperation: "It is very important that the Russian government consider carefully their continued support for the Assad regime."

A Syria without Assad is a worthy goal – as was an Iraq without Saddam Hussein. But the example of Iraq does not bode well for removing Assad by force and its doubtful whether the US under Trump has the skill to ensure his removal by political and diplomatic means.

Former British ambassador in Syria has links to Assad family

Blog post, 23 April 2017: Since leaving the diplomatic service Peter Ford, a former British ambassador in Damascus, has become an outspoken critic of western policies towards Syria and has described calls for President Assad to step down as "child-like".

During the conflict Ford has also repeatedly disputed evidence of atrocities by the Assad regime. Last September, when a UN humanitarian convoy was attacked in Aleppo killing 14 civilian aid workers and injuring at least 15 others, he suggested rebel fighters were responsible – even though the attack came from the air, and only Syrian and Russian air forces were operating in the area. A report by UN investigators later described the attack as "particularly egregious" and said:

"The types of munitions used, the breadth of the area targeted and the duration of the attack strongly suggest that the attack was meticulously planned and ruthlessly carried out by the Syrian air force to purposefully hinder the delivery of humanitarian aid and target aid workers, constituting the war crimes of deliberately attacking humanitarian relief personnel, denial of humanitarian aid and targeting civilians."

In February, Ford appeared in a radio programme produced by the Russian government's Sputnik News disputing a report by Amnesty International about atrocities in Saydnaya prison near Damascus. Amnesty had accused the Assad regime of carrying out mass extrajudicial killings at the prison "as part of an attack against the civilian population that has been widespread, as well as systematic, and carried out in furtherance of state policy".

Earlier this month, after bombing by the Syrian air force in Khan Sheikhoun led to dozens of people being killed by Sarin (or a similar banned substance) and hundreds more injured, Ford was again eager to exonerate the regime. Interviewed on BBC television, he told viewers it "is simply not plausible" and "it defies belief" that Assad would have used Sarin, and "he probably didn't do it".

On the same day, Ford could be seen on RT, the Russian propaganda channel, describing reports of the attack as "incredible". "It beggars belief," he said. "They [the Assad regime] had absolutely zero motive for doing it and a hundred reasons not to do it." (He has previously also spoken sympathetically about the regime on the Iranian channel Press TV.)

Meanwhile, in an unchallenging interview by former Guardian journalist Jonathan Steele, Ford told the Middle East Eye website it would be "out of character" for Assad to provoke the US by launching a chemical attack.

Promoting the interview on Twitter, Steele described Ford as "one of the bravest former ambassadors Britain has". Several other Twitter users praised Ford for his "very clear, level-headed assessment of recent events", for refuting "BBC propaganda" and dropping "truth bombs". Among others delighted by Ford's BBC interview was The Canary website which has previously hailed the Assad regime's "openness and tolerance", and which asserted "there is no evidence that Assad carried out the attack".

Ford's credentials as a former ambassador have misled some people into thinking his views on Syria are worth listening to. But what none of his many interviewers has so far mentioned (or perhaps even been aware of) is his connection with the Assad family.

Since February, Ford has been a director of the British Syrian Society which is headed by Assad's father-in-law, Fawaz Akhras.

The society, which is registered in Britain as a limited company, was founded in 2002 during a period when Assad, recently installed in power, seemed interested in reform. Numerous high-profile British figures with a background in foreign policy were happy to join it at the time.

Since the conflict broke out in Syria, however, the society has been mired in controversy – especially over Akhras's leadership. In 2012 it emerged that Akhras, a British-Syrian cardiologist and the father of Assad's wife, Asma, had been emailing advice to the president about how to rebut allegations of torture.

Records at Companies House show that no fewer than 28 people appointed at various times as directors of the society later resigned. It currently has seven directors, including Akhras and Ford. The only other British-based director is Syrian-born Ghayth Armanazi who was formerly head of the Arab League's mission in London. The remaining four directors – Ayman al-Chilabi, Costi Chehlaoui, Karim Khwanda and Omar Fouad Takla – are shown in the records as residents of Syria.

The society's published financial records are sketchy but the most recent accounts (2015) show assets of £131,000. There are no details of income and expenditure but earlier accounts show that between 2008 and 2011 it was spending on average £194,000 a year.

Syria's hexamine: a smoking gun

Blog post, 27 April 2017: It is now abundantly clear that the Syrian regime was responsible for the Sarin attack that killed dozens of people in Khan Sheikhoun earlier this month.

A declassified intelligence assessment released by the French government yesterday establishes beyond any reasonable doubt that the type of Sarin used had not only been manufactured by the regime but had also been used by the regime earlier in the conflict.

This means the regime is in breach of the Chemical Weapons Convention which it signed under international pressure following the Sarin attacks on Ghouta in 2013. It also means that the regime either failed to disclose its entire chemical weapons stockpile to UN inspectors or that it has since resumed production.

Although there is already plenty of evidence pointing to the regime's culpability in the Khan Sheikhoun attack, the French report adds two important pieces of new information. First, that the Sarin used there had a distinctive chemical signature that was "typical" of Sarin made by the regime and, secondly, that regime forces had used the same type of Sarin in an attack on Saraqeb in 2013.

What makes regime-produced Sarin distinctive is the inclusion of hexamine – an unusual additive which the regime apparently chose as a chemical stabiliser.

Apart from Khan Sheikhoun, hexamine has been detected from other Sarin attacks in Syria, including the Ghouta massacre. There is no doubt that the regime has been using hexamine for production of chemical weapons, because it said so itself. During inspections in 2013 it handed over 80 tonnes of the substance for destruction.

In 2013 the UN investigated seven alleged Sarin attacks in Syria, including one at Saraqeb in April that year. The Saraqeb attack didn't attract much attention at the time – probably because only one person died – but its significance is that the attack can be clearly attributed to regime forces and not, as the regime usually claims, to rebel fighters.

A helicopter flying high over the town was reported to have dropped items at three locations. One object is said to have landed in the courtyard of a house where it “intoxicated” some of the family members. A 52-year-old woman who had been severely affected was transported to Turkey where she died. The UN's report said:

“During an autopsy that was observed by members of the United Nations Mission, samples of several organs from the deceased woman’s body were recovered for subsequent analysis. The results from most of these organs clearly indicated signatures of a previous Sarin exposure.”

At the time, the inspectors – who could not visit the site – were unable to reach any definite conclusions. Their report said the evidence suggested that chemical weapons had been used but "in the absence of primary information on the delivery system(s) and environmental samples collected and analysed under the chain of custody, the United Nations mission could not establish the link between the alleged event, the alleged site and the deceased woman".

However, the French report takes this story much further. Regarding the three objects dropped from the sky, it says:

"At the first point of impact, there were no victims. At the second point of impact, one person was killed and about 20 injured. An exploded grenade was found in the wreckage. Analysis of biomedical and environmental samples collected by the French services revealed the presence of compounds consistent with exposure to sarin. This analysis was confirmed

by the United Nations in December 2013."At the third point of impact, an unexploded grenade was found in a crater on a dirt track. This munition was very similar in appearance to that found at the second point of impact. Once the French services were sure of the traceability of the grenade, analyses were carried out.

"The chemical analyses carried out showed that it contained a solid and liquid mix of approximately 100ml of sarin at an estimated purity of 60%. Hexamine, DF and a secondary product, DIMP, were also identified."

The French report also notes that only the Syrian armed forces had helicopters – the rebels had none – and that studies of the impact crater "confirmed with a very high level of confidence" that the object was dropped from the air.

The report continues:

"The sarin present in the munitions used [at Khan Sheikhoun] on 4 April was produced using the same manufacturing process as that used during the sarin attack perpetrated by the Syrian regime in Saraqeb. Moreover, the presence of hexamine indicates that this manufacturing process is that developed by the Scientific Studies and Research Centre for the Syrian regime."

Although the Saraqeb attack took place before Syria became a party to the Chemical Weapons Convention, the more recent Khan Sheikhoun attack points to cheating by the regime. The French report says:

"France assesses that major doubts remain as to the accuracy, exhaustiveness and sincerity of the decommissioning of Syria’s chemical weapons arsenal. In particular, France assesses that Syria has maintained a capacity to produce or stock sarin, despite its commitment to destroy all stocks and capacities. Lastly, France assesses that Syria has not declared tactical munitions (grenades and rockets) such as those repeatedly used since 2013."

Last week Israel claimed that the regime has retained "between one and three tons" of undeclared chemical weapons. The French report, meanwhile, says inspectors from the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) have been unable to obtain any proof of the veracity of Syria’s declarations. It adds: "The OPCW itself has identified major inconsistencies in Syria’s explanations concerning the presence of sarin derivatives on several sites where no activity relating to the toxin had been declared."

Syria, Seymour Hersh and the Sarin denialists

Blog post, 1 July 2017: Do news organisations have a duty to publish stories from anonymous sources when there is reason to believe they are untrue? Apparently some people think so.

Yesterday, following scientific tests, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons confirmed that inhabitants of Khan Sheikoun, in the Syrian province of Idlib, had been "exposed to Sarin, a chemical weapon", during an attack last April. Reports at the time said at least 74 died and hundreds were injured.

The news that Sarin had definitely been involved caused a buzz on Twitter from people refusing to believe it. Many pointed instead to an article in a German newspaper last weekend which quoted an unnamed "senior adviser to the American intelligence community" as saying no chemical attack had taken place.

The article, by veteran American journalist Seymour Hersh, suggested that Syrian forces using a conventional explosive bomb had accidentally hit a store of "fertilisers, disinfectants and other goods" causing "effects similar to those of sarin".

Hersh's version contradicted evidence from a range of sources and, in the light of yesterday's announcement from the OPCW, is clearly untrue. As far as some people were concerned, though, it said what they wanted to hear and, even after the OPCW reported its findings, they were still complaining that mainstream media had failed to take Hersh's ridiculous story seriously.

An article on The Canary Website began:

"An acclaimed investigative journalist [Hersh] has now blown a giant hole in the official narrative of one of 2017's most explosive world events: the Syrian 'chemical attack' and Donald Trump’s fierce response. But the BBC and other media outlets seem to be completely ignoring his exposé."

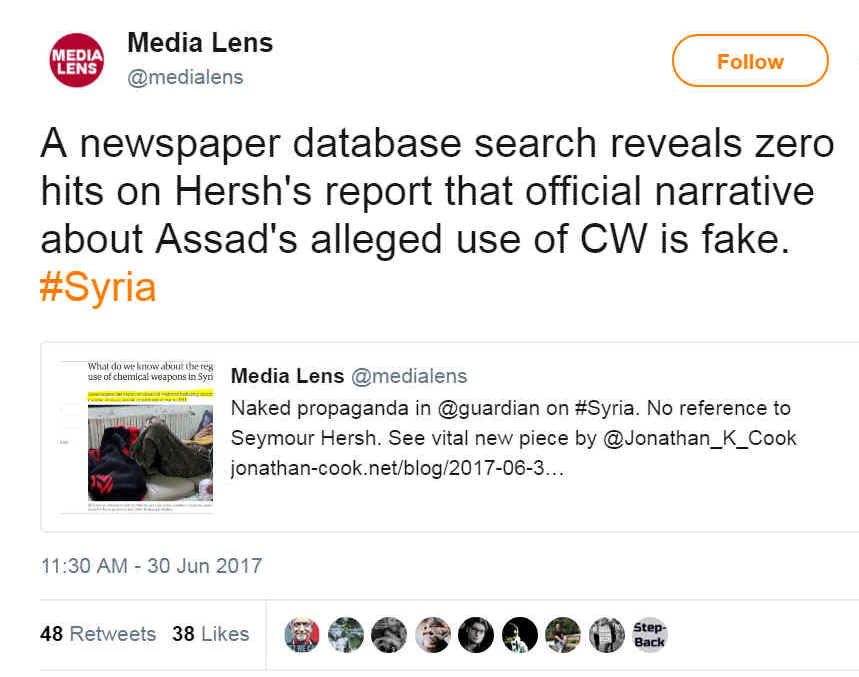

Media Lens, an organisation dedicated to "correcting for the distorted vision of the corporate media" grumbled that searching a database of newspapers had revealed no mentions of Hersh's article.

Meanwhile Jonathan Cook, a journalist who mainly reports on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, wrote in a blog post:

"If you wish to understand the degree to which a supposedly free western media are constructing a world of half-truths and deceptions to manipulate their audiences, keeping us uninformed and docile, then there could hardly be a better case study than their treatment of Pulitzer prize-winning investigative journalist Seymour Hersh.

"All of these highly competitive, for-profit, scoop-seeking media outlets separately took identical decisions: first to reject Hersh’s latest investigative report, and then to studiously ignore it once it was published in Germany last Sunday. They have continued to maintain an absolute radio silence on his revelations ..."

But why should anyone pay attention to Hersh when an anonymous source tells him something that flies in the face of evidence? The reason, apparently, is that he won a Pulitzer prize for journalism 47 years ago. His supporters constantly mention the Pulitzer as if that's a good reason for unquestioning faith in whatever he writes.

Winning a Pulitzer obviously means a reporter's work has impressed the judges but it's not necessarily a guarantee of factual accuracy. In 1981, one of the winners was a Washington Post journalist whose story about an eight-year-old heroin addict later turned out to be fabricated.

Hersh has certainly done valuable reporting in the past. He exposed the Mai Lai massacre in Vietnam back in 1969 and, more recently, the horrors of Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Some of his other exposés have misfired, though, and he has often been criticised for his use of shadowy sources. In the words of one Pentagon spokesman, Brian Whitman, he has "a solid and well-earned reputation for making dramatic assertions based on thinly sourced, unverifiable anonymous sources".

Another complaint about his more recent work is that he spends too much time listening to his unidentified sources and not enough looking at open-source evidence which points in a different direction. In an earlier article where Hersh suggested the Assad regime had not been responsible for Sarin attacks near Damascus in 2013, he either overlooked or disregarded evidence which didn't fit his argument and posed a number of questions which other writers had already answered.

His 2013 article about chemical weapons in Syria was rejected by the New Yorker magazine and eventually published in Britain by the London Review of Books. However, the London Review of Books rejected his latest article – which is why it ended up being published in Germany.

Inevitably, Hersh's loyal supporters discount the most likely reason for these rejections – that his editors found the articles flaky – in favour of a media conspiracy. Jonathan Cook (this time writing for Counterpunch) says:

"Paradoxically, over the past decade, as social media has created a more democratic platform for information dissemination, the corporate media has grown ever more fearful of a truly independent figure like Hersh. The potential reach of his stories could now be enormously magnified by social media. As a result, he has been increasingly marginalised and his work denigrated. By denying him the credibility of a 'respectable' mainstream platform, he can be dismissed for the first time in his career as a crank and charlatan. A purveyor of fake news."

This may explain why Media Lens, which specialises in critiquing the mainstream media, has such a high opinion of Hersh.

Media Lens has previously taken a dim view of journalists who use anonymous sources. A few years ago it bombarded the Guardian with complaints over a news story about Iraq which extensively quoted unnamed American officials. These sources, Media Lens said, were used "with no scrutiny, no balance, no counter-evidence – nothing".

Exactly the same charges can be levelled against Hersh but Media Lens not only seems unperturbed but is urging other media to regurgitate his anonymously-sourced story.

To some extent, scepticism about chemical weapons in Syria is a knee-jerk reaction to misleading reports about Iraq's imaginary weapons of mass destruction in the run-up to the 2003 invasion: if we were deceived over Iraq, how do we know we are not being deceived over Syria?

The best protection against that – then, as now – is evidence. Regardless of who is claiming what, check for evidence that might support their claims.

In Syria there is abundant evidence that Sarin has been used as a weapon during the conflict. The Assad regime, by its own admission, had stockpiles of Sarin – and possibly still has some. It also denies that any has been lost, stolen or captured. Furthermore, there is no evidence that rebel groups fighting in Syria have ever possessed or had access to Sarin. Draw your own conclusions.

In Iraq, on the other hand, suspicions about Saddam Hussein's weapons were not supported by evidence. During the long build-up to war, constantly repeated claims from politicians and others led many prominent journalists to abandon their critical faculties. But, as with Hersh's Syria articles, warning signs were there if only people looked for them.

The Washington Post, for example, devoted an extraordinary 1,800 words to an extremely flimsy (but scary) story suggesting Iraq had supplied nerve gas to al-Qaida.

At the New York Times, star reporter Judith Miller was churning out more alarmist stuff. One story concerned US attempts to stop Iraq importing atropine, a drug used for treating heart patients which is also an antidote against pesticide poisoning ... and nerve gas. This tale, as presented by Miller (with assistance from anonymous official sources) was that Iraq not only possessed nerve gas but intended to use it and wanted to protect its own troops from the harmful effects.

Another of Miller's "scoops" was an unverified claim that a Russian scientist, who once had access to the Soviet Union's entire collection of 120 strains of smallpox, might have visited Iraq in 1990 and might have provided the Iraqis with a version of the virus that could be resistant to vaccines and could be more easily transmitted as a biological weapon.

Unfortunately, there were plenty who took her word for it at the time. She was, after all, a Pulitzer prize-winning investigative journalist.

Syria and Sarin: who was Hersh's anonymous source?

Blog post, 4 July, 2017: On 4 April, Syrian government forces carried out an airstrike on Khan Sheikhoun in Idlib province which, according to reports at the time, killed at least 74 people and injured hundreds more. Scientific tests by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons – an inter-governmental body – have since established that inhabitants of Khan Sheikoun were "exposed to Sarin, a chemical weapon", during the attack.

Last month, however, a German newspaper published a long and deeply flawed article disputing the use of Sarin as a chemical weapon in Khan Sheikhoun. Written by the celebrated American journalist Seymour Hersh and published in Welt, it quoted an unnamed "senior adviser to the American intelligence community" as saying no chemical attack had taken place. Instead, it suggested that Syrian forces using a conventional explosive bomb had accidentally hit a store of "fertilisers, disinfectants and other goods" causing "effects similar to those of sarin".

Even though it's clear that Sarin was used, supporters of Hersh on social media have continued demanding that major news organisations should report his "alternative" version and treat it seriously – mainly on the grounds that Hersh has exposed some important stories in the past and that he once won a Pulitzer prize for journalism (47 years ago).

According to Hersh's story (which had been rejected by the London Review of Books before it appeared in Welt), the Syrian forces' intended target was "a jihadist meeting site" – a two-storey building where the upper floor was used by rebels as "a regional headquarters".

Again, according to Hersh, the attack on this building had been well-prepared and the Americans were notified about it in advance:

"Russian and Syrian Air Force officers gave details of the carefully planned flight path to and from Khan Shiekhoun on April 4 directly, in English, to the deconfliction monitors aboard the AWACS plane, which was on patrol near the Turkish border, 60 miles or more to the north."

Citing his unnamed source, Hersh says Syrian forces hit the building with a bomb which "triggered a series of secondary explosions that could have generated a huge toxic cloud that began to spread over the town, formed by the release of the fertilisers, disinfectants and other goods stored in the basement".

Hersh continues:

"Evidence suggested that there was more than one chemical responsible for the symptoms observed ... The range of symptoms is, however, consistent with the release of a mixture of chemicals, including chlorine and the organophosphates used in many fertilisers, which can cause neurotoxic effects similar to those of sarin."

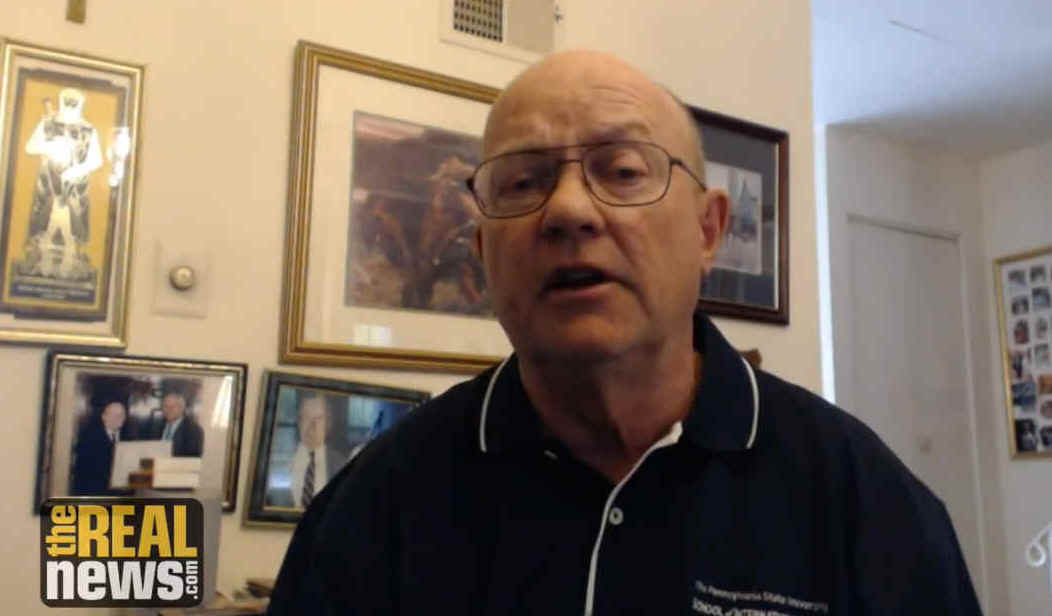

One unanswered question about this is the identity of Hersh's anonymous source – and a possible clue can be found on a website called The Real News Network. Three days after the Khan Sheikhoun attack, The Real News Network posted a video interview with a retired US Army colonel, Lawrence Wilkerson, who described reports of a Sarin attack as a hoax.

The account of events given by Wilkerson has some interesting similarities with the account given by Hersh in his Welt article almost three months later. Wilkerson told The Real News Network:

"Most of my sources are telling me, including members of the team that monitors global chemical weapons, including people in Syria, including people in the US intelligence community, that what most likely happened – and this intelligence, by the way, was shared with the United States, by Russia in accordance with the Deconfliction Agreement we have with Russia – that they hit a warehouse that they had intended to hit. And had told both sides, Russia and the United states, that they were going to hit.

"This is the Syrian air force, of course. And this warehouse was alleged to have ISIS supplies in it, and, indeed, it probably did, and some of those supplies were precursors for chemicals. Or, possibly an alternative, they were phosphates for the cotton growing, fertilising the cotton-growing region that's adjacent to this area. And the bombs hit, conventional bombs, hit the warehouse, and because of a very strong wind, and because of the explosive power of the bombs, they dispersed these ingredients and killed some people."

In comparing these two accounts, a small point worth noting is that they both talk – apparently mistakenly – about symptoms caused by fertiliser. In a critique of Hersh's article on the Bellingcat website, Eliot Higgins wrote:

"He [Hersh] describes the symptoms seen in victims as 'consistent with the release of a mixture of chemicals, including chlorine and the organophosphates used in many fertilisers, which can cause neurotoxic effects similar to those of sarin.' Here it is worth pointing out that organophosphates are used as pesticides, not fertilisers, and it’s unclear if this error is from Hersh himself or his anonymous source."

Could this be an indication that Wilkerson was Hersh's source? In his article, Hersh describes the source as "a senior adviser to the American intelligence community" and later adds that the source "has served in senior positions in the Defense Department and Central Intelligence Agency".

Wilkerson, in addition to his military career, was chief of staff to US secretary of state Colin Powell from 2002 to 2005 and, among other things, helped to prepare Powell's notorious presentation to the UN Security Council about Iraq's alleged weapons of mass destruction. However, he has since become a fierce critic of the way the war was conducted.

Interviewed in 2006, he said:

"My participation in that presentation [by Powell] at the UN constitutes the lowest point in my professional life. I participated in a hoax on the American people, the international community and the United Nations Security Council. How do you think that makes me feel?"

This experience probably goes a long way towards explaining Wilkerson's reluctance to accept that Sarin has been used in Syria.

One discrepancy between Hersh's description of his source and Wilkerson's CV is that Wilkerson does not appear to have held a position in the CIA, though he has certainly worked with classified intelligence material – for example in preparing Colin Powell's UN report on Iraq.

If Wilkerson was Hersh's source for the Khan Sheikhoun article, we might also ask why Hersh didn't identify him by name (since he was already on record as saying some of the things that Hersh reported).

However, if Wilkerson was not the source it seems very likely, given the similarity in the two accounts, that they both share the same original source.

There's a further pointer towards Wilkerson himself, though. It has since emerged that Welt spoke directly to Hersh's source before publishing the article, and that the source was one Hersh had used previously for his 2004 exposé of atrocities at Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq.

While working at the State Department under Colin Powell, Wilkerson was a key figure investigating the events at Abu Ghraib. He was shocked by what he found and was later identified as "the Bush administration's whistleblower" in the affair.

Syria agrees that Sarin was used in Khan Sheikhoun

Blog post, 5 July, 2017: Surprising as it might seem, both the Syrian government and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) agree that people were exposed to Sarin in Khan Sheikhoun last April.

This should now become the starting point for any rational discussion of what happened there. Following the latest results from chemical tests there is simply no point in anyone talking about hoaxes or claiming the deaths and injuries were caused by bombs hitting supplies of disinfectant or fertiliser.

Even a bomb hitting stores of Sarin would not cause the effects seen in Khan Sheikhoun. The only logical conclusion is that the Sarin detected in the town had been used as a weapon – in which case the main question yet to be finally resolved is who did it.

The 78-page report circulated by the OPCW this week describes the fact-finding team's investigation and the methodology used: the interviews with witnesses, the symptoms found on victims, the samples taken from their bodies and the incriminating chemical traces detected by laboratory analysis. Summarising its findings, the OPCW says:

"The analyses of the samples indicate not only the presence of sarin, but also other chemicals including potential impurities and breakdown products related to sarin, depending on the production route and the raw materials used.

"By reviewing, in conjunction, the evidence relating to autopsy records, biomedical specimens, hospital records, witness testimony, photographs and video supplied during interviews, and environmental samples, the FFM [Fact-Finding Mission] concludes that a significant number of people were exposed to sarin, of which a proportion died from that exposure."

There was one significant gap in the team's investigation, though. In the immediate aftermath of the attack they were unable to visit Khan Sheikhoun – a rebel-held town – to collect samples from the scene of the alleged attack or examine fragments from any munitions said to have been involved.

The report explains:

"Owing to such factors as security concerns in the region of the alleged incident, the time frame of events – whereby no permission was in place when the team initially deployed, which would have provided the best circumstances for evidence retrieval – and some casualties and other witnesses had been transferred to a neighbouring State Party, it was determined that the risk of a visit to the incident area would be prohibitive for the team."

It goes on to say that the longer it took to get to the site the less benefit there would be:

"The scientific and probative value of visiting the site diminishes over time, particularly if it is not possible to manage access to the site. Hence, the evidentiary value of samples taken close to the time of the allegation, supported by photographic and video evidence and in association with witness testimony, needs to be balanced against the evidentiary value of the FFM visiting the site some time later to collect its own samples."

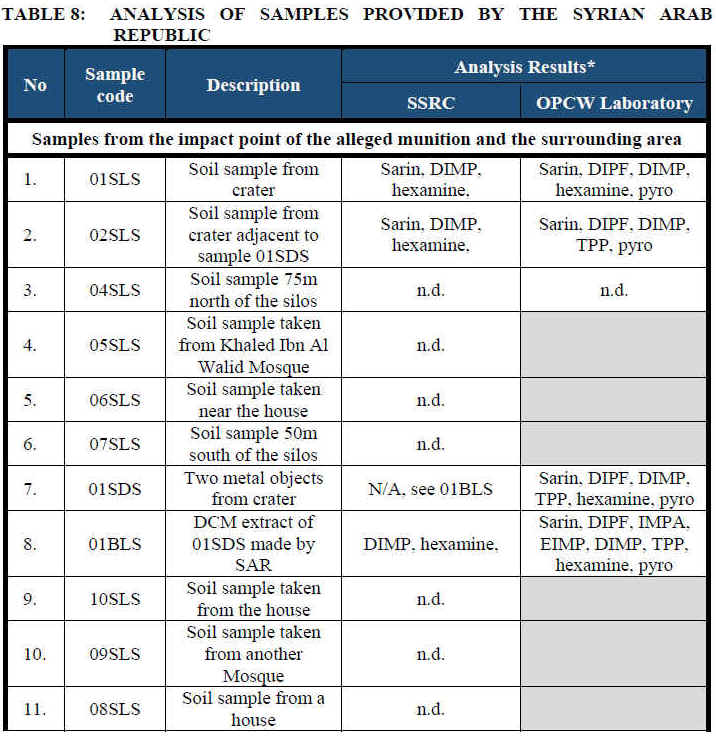

However, an unlikely helper stepped in – in the shape of the Syrian government who told investigators that an unnamed "volunteer" from Khan Sheikhoun had provided them with samples. These included soil, fragments of metal, bone, and vegetation. According to the Syrian authorities, one of these soil samples and the metal fragments had come from the crater which locals say was the point where the chemical weapon struck. The other samples were said to have come from various spots in the surrounding area.

The Syrian authorities also provided OPCW investigators with a video showing the samples being collected.

The samples were then split so that each could be tested separately by both the Syrian government's Scientific Studies and Research Centre and a laboratory designated by the OPCW.

The results of these two sets of tests were broadly the same.

The Syrians and the OPCW agreed that the soil from the crater and another sample from adjacent to the crater had tested positive for Sarin, DIMP (a by-product of Sarin production) and hexamine (used as an acid scavenger in Sarin made by the Syrian government). Additionally, the OPCW lab found evidence of other Sarin-linked chemicals.

The Syrians and the OPCW also agreed that extraction samples from metal objects in the crater tested positive for DIMP and hexamine. The OPCW lab additionally detected Sarin and other Sarin-linked chemicals.

Needless to say, the Syrian authorities are now pretending that this didn't happen. A statement from the foreign ministry in Damascus on Saturday dismissed the OPCW's report (and the Syrian government's contribution to it) as lacking "any credibility".

Chemical weapons in Syria: the search for culprits begins

Blog post, 7 July, 2017: It is now beyond dispute that banned chemicals have been used in the Syrian conflict. Aside from a few conspiracy theorists, all sides – including the Russian and Syrian governments – accept this as fact, though they disagree about who is responsible.

We have reached this point because of painstaking work by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons over the last four years in gathering evidence. The OPCW's Fact Finding Mission is continuing its investigations in Syria but during the next few months a joint UN/OPCW team will also be working "to identify, to the greatest extent feasible, perpetrators who use chemicals as weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic".

This team, known in UN-speak as the Joint Investigative Mechanism (or JIM for short), has a three-person leadership panel headed by Edmond Mulet from Guatemala. He is assisted by Malaysian-born Judy Cheng-Hopkins and Stefan Mogl from Switzerland. The panel hopes to report back in mid-October.

Investigator Edmond Mulet: working "to identify, to the greatest extent feasible, perpetrators who use chemicals as weapons in the Syrian Arab Republic"

Initially, the JIM will focus on two specific incidents. One is the Sarin attack in Khan Sheikoun on 4 April which, according to reports at the time, killed at least 74 people and injured hundreds more. The other is a mustard gas attack in Um Housh, in Idlib province, last September which injured two women.

However, these may not be the only ones. At a press conference yesterday, Mulet said the OPCW is currently working on "six or seven other cases that might come our way before the end of October".

The focus on Um Housh in addition to Khan Skeihoun appears to be a compromise in order to secure Russian agreement for the JIM investigation to go ahead. Although Um Housh was far less serious in terms of casualties it nevertheless involved a banned weapon and Russians have been eager to highlight it – presumably because (unlike the Khan Sheikhoun attack) locals blamed ISIS.

One criticism of the recent OPCW report on Khan Sheikhoun is that the Fact Finding Mission did not visit the town or Shayrat airbase from where the attack is thought to have been launched. Following the use of Sarin in Khan Sheikhoun, Donald Trump ordered strikes on Shayrat with 59 Tomahawk cruise missiles at an estimated cost of $49 million.

At yesterday's press conference, Mulet said: "It is our intention to visit al-Shayrat base in order to go to the site, and we also would like to go to Khan Sheikhoun. But of course that is related to security concerns and security issues."

The pros and cons of visiting both these places were discussed by Aron Lund of the Century Foundation in an article published on 30 June. As the recent OPCW report noted, it is questionable whether much useful information can be gathered in Khan Sheikhoun so long after the event. The need for an inspection visit to Khan Sheikhoun has been further reduced by the OPCW's revelation in its report that the Syrian government provided samples said to have been collected in the town which tested positive for Sarin.

At the press conference, Mulet appeared to suggest that visits to Khan Sheikhoun and Shayrat would be conditional on the Syrian government cooperating over related matters. He said:

"Before we are going to these places I would need some feedback from the Syrian government. I need information about the flight logs in al-Shayrat, the movements around al-Shayrat. I need the names of the people we will be interviewing – military commanders and government officials – and also some information that the Syrian government could provide to us in order to conduct our work. So, we are working already with the Syrian government on this, and hopefully we will be given the necessary tools and instruments in order to our work."

As a party to the Chemical Weapons Convention, Syria has an obligation to cooperate. How far it will do so, though, is still an open question. This raises the possibility of cat-and-mouse antics similar to those with UN weapons inspectors in Iraq which led, eventually, to the US-led invasion of 2003.

It is important to avoid that. Clearly, there are some who would like to make chemical weapons an excuse for deeper military involvement in Syria but I have argued several times before (here and here) that the chemical issue should be kept as separate as possible from the wider confict.

The banning of chemical weapons has been a great example of international and so far only three countries and to date only three countries – Egypt, North Korea and South Sudan – have neither signed nor ratified the convention. Failure to confront the use of chemical weapons in Syria would blow a huge hole in what has been achieved so far and signal to others that they can use them with impunity.

But cruise missiles won't help. What it needs is a careful, patient, evidence-based and sustained effort by the UN to bring those responsible for poisoning people in Syria to justice – no matter how long it takes.

Did Syrian rebels acquire sarin? If so, how?

Blog post, 17 July, 2017: The banned nerve agent sarin has been used repeatedly in the Syrian conflict, as laboratory tests have confirmed. There are disputes, though, about who has been using it. Syrian rebels, along with western governments, blame the Assad regime while the regime, supported by Russia and Iran, blames the rebels.

The regime, by its own admission, had a chemical weapons programme that produced large quantities of sarin, but could rebel fighters have acquired sarin too? If they did, there are three ways they might have got it:

1. By making it themselves

2. By getting it from a foreign supplier

3. By stealing it from the Syrian government

Home-made sarin?

Russian officials have fequently suggested that the sarin used in Syria could be "home-made" and the Syrian president, Bashar al-Assad, has asserted that “anyone can make sarin in his house”. In a similar vein, the American journalist Seymour Hersh, who has written several articles about chemical attacks in Syria, told a CNN interviewer: "It's not hard to make sarin. You can mix it in the backyard – two chemicals melded together."

This gives the impression that all you need is a few pots and pans plus the right ingredients. But it's more complicated than that.

It's true that a chemist, working in a laboratory and taking suitable precautions, could make a tiny amount of sarin without undue difficulty but producing it in the quantities needed for chemical weapons is a very different proposition.

Worldwide, there is only one known example of anyone other than a government manufacturing sarin on a significant scale. This was the Japanese doomsday cult, Aum Shinrikyo, which used sarin to kill 12 people on the Toyko subway and eight others in a separate attack at Matsumoto in the 1990s.

Aum's production methods give some idea of what Syrian rebels would be up against in trying to make their own sarin.

The cult had plenty of money and it spent $10 million setting up a secret factory which was known as Satyan 7 and designed to look like a shrine to the Hindu god Shiva. It is described by Amy Smithson in a study of chemical and biological terrorism:

"The entrance of Satyan 7 was a shrine that disguised the facility’s real purpose. Above a huge styrofoam statue of the head of Shiva was the 'Room of Genesis', chocked with tanks holding nerve gas precursor chemicals. Behind Shiva was a two-storey distillation column.

“Further into the building were three laboratories, a computer control center, and the fabrication area with its five reactors, injectors, piping, wiring, and heating. The equipment was corrosion-resistant Hastelloy, well-suited for making chemical warfare agents.

"The fifth reactor in this suite was state-of-the-art – a $200,000 Swiss-built, fully computerised model with automatic temperature and injection controls plus analytical and record keeping features ... Next door to Satyan 7 was a laboratory that alone cost an estimated $1 million to build, filled with hundreds of thousands of dollars of analytical equipment.

“Satyan 7 had some built-in safety features, such as hatchways that sealed off rooms in the event of accidents, ventilation, and a decontamination chamber. Technicians wore gas masks and full-body chemical suits during certain operations, such as sampling. Closed-circuit television recorded activities in the production area.”

Satyan 7 never came close to its intended production target of two tons a day. According to sources cited by Smithson it produced only 20 litres of sarin over a two-month period in 1994 before something went wrong and it had to be shut down. Twenty litres is less than half what would be needed to fill just one of the rockets used in the 2013 attack on Ghouta in Syria.

After reading Smithson’s report, anyone thinking of making their own sarin in secret might well conclude that it isn’t worth the effort.

Despite all the technology used by Aum, its sarin was not of a very high quality. According to Åke Sellström, the chief UN investigator, the sarin used in Ghouta was not only superior to that used by Aum in Japan but also superior to that used by Iraq in its war with Iran. This strongly suggests it was not home-made but came from some government source.

One of the problems at Satyan 7 was finding the right people to operate it. The cult seemed to have little trouble recruiting young and highly educated scientists and engineers but they lacked practical experience. After the emergency shut-down in 1994, Aum tried to get it running again by seeking out Russian chemical-weapons engineers, but to no avail.

Another problem with trying to make sarin in secret is the noxious waste. One calculation, based on German experience, is that for every ton of sarin produced there will be at least seven tons of waste which would have to be disposed of harmlessly and without attracting attention. Satyan 7 ran into trouble on that account when neighbours complained to police about the unpleasant smells.

Shopping for raw materials

In order to make their own sarin, Syrian rebels would need to obtain the relevant chemicals – and preferably in a way that did not arouse suspicion. Aum did this in Japan by buying them through front companies.

However, the effect of Aum’s attacks was to raise awareness of the threat from chemical and biological terrorism, prompting new efforts to counter it. Anyone trying to buy the ingredients for sarin today would have more difficulty and face a greater risk of being caught than Aum did in the 1990s.

Towards the end of May 2013, police in Turkey arrested 12 people who were said to be connected with the Syrian rebel group Ahrar al-Sham and/or the Nusra Front. Initial reports said they had been caught with 2 kg of sarin (though according to later reports it turned out to be anti-freeze).

Six of the suspects were released almost immediately but the authorities claimed the remaining six – five Turkish citizens and a Syrian – had been trying to buy chemicals to make sarin. They were charged with attempting to acquire weapons for a terrorist organisation and the Syrian, Haytham Qassab, was also charged with belonging to a terrorist organisation.

The timing of the arrests was interesting because it came just a few weeks after first reports of chemical weapons use started circulating in Syria and the government and rebels began accusing each other.

When the case came to trial at the end of 2015, the five Turks were acquitted while Qassab – who had been released earlier and was not in court – was given a 12-year sentence.

Exactly what lay behind this affair is far from clear, partly because the case became politicised. Turkish opposition MP Eren Erdem appeared on the Russian RT channel alleging a cover-up and the government responded by threatening him with treason charges.

However, it does seem that Qassab had been a regular purchaser of military and medical supplies for Syrian rebels. Prosecution documents said he had moved to Antakya in Turkey on the instructions of Abu Walid, leader of the Ahrar al-Sham Brigades. He was quoted as saying:

“After I arrived in Antakya, other rebel groups had come into contact with me. While some had asked me for medicine and other humanitarian aid supplies, others wanted to obtain military equipment.”

According to the Turkish prosecutors, his sarin-related shopping list consisted of the following items:

- Timed fuses

- Chrome pipes

- Thionyl Chloride (SOCl2)

- Potassium Fluoride (KF)

- Methanol (CH3OH)

- Isopropanol (C3H8O)

- Isopropanolamine (C3H9NO)

- White Phosphorus (P4)

- Medical Glucose

- Bauxite

To demonstrate a connection between this and sarin, the Turkish authorities proposed a five-step formula:

1. Methanol (CH3OH) + White phosphorous (P4) = Dimethylmethylphosphonate (DMMP)

2. DMMP + Thionyl Chloride (SOCl2) = Methylphosphonyldichloride (DC)

3. DC + Potassium Fluoride (KF) = Methylphosphonyldifluoride (DF)

4. DF + Isopropanol (C3H8O) = Sarin (C4H10FO2P) + Hydrogen Fluoride (HF).

5. Add Isopropanolamine (C3H9NO) to neutralise the corrosive HF.

Whether that would actually result in sarin is a matter of dispute. Dan Kaszeta, a security consultant with experience in chemical weapons, says:

"This hasn’t even been cribbed from easily available documents on the internet. Indeed, I cannot rule out that an obviously fake recipe has been circulated for purposes of deception or mischief. If I wanted to write a recipe for sarin that looked broadly correct, but which would never result in any actual sarin (or even harm the producers) it is the sort of thing I would do."

Kaszeta explains his reasoning here. Others have expressed different views (here and here) but there does seem to be agreement that if rebels were trying to buy isopropanolamine they had got the name wrong and should probably have been looking for isopropylamine instead.

At its most incriminating, the Turkish case indicates an attempt by rebels to acquire precursors for sarin. It does not show they had an ability to make it, and there is no evidence they had acquired the necessary equipment.

It’s also worth noting that two of the chemicals on the shopping list cannot be bought in Turkey without government approval, so if Qassab went looking for them there was a fairly high chance of being caught. This suggests another possibility – that Qassab might have been set up for entrapment by agents working for the Syrian government or perhaps even the Turkish government.

Sarin from abroad?

Instead of trying to make their own sarin, an alternative course for Syrian rebels would be to seek out ready-made supplies from abroad. This was something the Japanese Aum cult had initially tried (and failed) to do before deciding to manufacture it. Aum contacted what it thought was a rogue operation in the United States illicitly selling nerve gas but its would-be supplier turned out to be an undercover arm of the US Customs Service.

The Syrian and Russian governments have both encouraged the notion of rebel fighters receiving sarin from abroad but have not been forthcoming with any details. In 2014, following discussions with the Syrian authorities, Åke Sellström, the chief UN weapons inspector in Syria, said: “They have quite poor theories: they talk about smuggling through Turkey, labs in Iraq.” The lack of any supporting evidence puzzled Sellström:

“To me it is strange. If they really want to blame the opposition they should have a good story as to how they got hold of the munitions, and they didn’t take the chance to deliver that story.”

Sarin from Iraq?

Among the suggested foreign sources for rebel sarin, neighbouring Iraq, with its porous border, is perhaps the most obvious. ISIS is active on both sides of the border and is known to have used chlorine and mustard gas as chemical weapons.

In the Iraqi city of Mosul last September, American warplanes bombed what was said to be “a chemical weapons production facility” which also served as an ISIS headquarters building.

According to news reports the building was a converted pharmaceutical factory. But it does not appear to have been producing sarin and there have been no reports of ISIS using sarin in Iraq.

Video of the US-led airstrike on the alleged chemical weapons factory operated by ISIS in Mosul, Iraq

Last November, John Dorrian, a US military spokesman in Iraq described ISIS's ability to use chemical weapons as “rudimentary”. He told the New York Times typical weapons used in these attacks were rockets, mortar shells or artillery shells filled with chemical agents which had little effect beyond the immediate area where they landed.

Around the same time a report by IHS Conflict Monitor said the “most likely” chemical threat emanating from ISIS in Mosul was from chlorine and mustard agents. There was also, “to a much lesser extent”, the possibility of a “dirty bomb” in which radioactive materials seized from hospitals could be scattered using conventional explosives. The report gave no indication that ISIS was producing sarin in Mosul and, even if had been doing so, that would not explain why sarin attacks in Syria began in 2013, since ISIS did not capture Mosul until June 2014.

But could ISIS have obtained sarin left over from the Saddam Hussein era? Also in June 2014 – again, too late to account for the earliest sarin attacks in Syria – ISIS overran a disused chemical weapons facility at Muthanna, north-west of Baghdad, and began looting it.

One section of this complex, Bunker 13, contained 2,500 sarin-filled 122mm chemical rockets which had been produced and filled before the 1991 Gulf war. However, both the UN and US insisted these weapons were not in a usable state. The UN said the bunker had been bombed during the Gulf war, and the rockets were "partially destroyed or damaged". US state department spokeswoman Jen Psaki said the bunker contained "degraded chemical remnants". There were no “intact chemical weapons” and it would be “very difficult, if not impossible, to safely use this for military purposes or, frankly, to move it".