A few months ago I began to feel that something odd was happening whenever I posted a tweet about Bahrain. My tweets, usually critical of Bahrain's government, rapidly disappeared from view – pushed down the #bahrain live Twitter feed by lots of newer tweets, mostly supporting the Bahraini government.

Of course, that's the way Twitter works: older tweets fade into near-oblivion as new ones are posted. But I got the impression that this was happening much more quickly with #bahrain than other hashtags that I use.

Yesterday evening I decided to test this impression by counting the number of tweets posted during a 10-minute period under several different hashtags. For #bahrain I counted 59 new tweets – almost three times the number for #egypt, which had 20. The hashtag #kuwait got only eight tweets in 10 minutes and #qatar got six.

This random check might not be very scientific but it does suggest I wasn't imagining things; that considering Bahrain is such a tiny country (population 1.4 million) the #bahrain hashtag is remarkably active – even hyperactive.

There could be all sorts of reasons but Marc Owen Jones, who lectures in Gulf politics at Tübingen University in Germany and is co-author of a book on Bahrain, has an interesting explanation: that most of the #bahrain tweets are not from real people but from robots.

Out of 10,887 #bahrain tweets posted during one 12-hour period this week, he identified 5,556 as "most likely produced by bots" – automated Twitter accounts.

He began to investigate after noticing a series of identical tweets which attacked Isa Qasim, the prominent Shia cleric who has been stripped of his nationality by Bahrain's rulers. Although the tweets had exactly the same wording they were not re-tweets and appeared to have been posted by large numbers of individuals – presumably to create an impression that the Bahraini regime's action against Qasim has popular support. (I wrote about that aspect in a blog post yesterday.)

Twitter reacted to that discovery by suspending around 1,800 suspected robotic accounts, but hundreds more are still busy tweeting. Besides supporting the government of Bahrain, their tweets express sectarian and anti-Shia views – often in offensive language.

Marc Owen Jones continued to investigate and has now produced another report which explains in detail why the hundreds of sectarian and pro-government accounts posting under the #bahrain hashtag are almost certainly fakes.

One reason for suspicion is that the relevant Twitter accounts were created in batches. For example, around 100 accounts were created over four consecutive days in August 2013. Another batch – of 200 accounts – was created between 6 and 11 June 2014.

A key difference between human Twitter accounts and robotic accounts is that humans usually tweet when motivated to do so, not at fixed intervals. A robot that is programmed to tweet every hour, on the hour, is thus liable to be spotted quickly.

But whoever is behind the #bahrain accounts has gone to a lot of trouble to disguise their robotic behaviour. The accounts have a variety of tweeting patterns, and some of the patterns are quite complex. For example, one of those investigated by Owen Jones had been set up to post two tweets four seconds apart, at intervals of 12 minutes 20 seconds.

Despite those efforts at disguise, if you look carefully at the individual accounts it soon becomes obvious that they are not real. For instance, there are a lot of similarities among the 40-plus accounts in one batch created in February this year. Mostly, they follow 50-60 other accounts and have only a handful of followers themselves. They seem generally disengaged from the Twitter community and are hardly ever retweeted.

The February 2016 accounts have vague biographical notes often mentioning Allah which, to quote Marc Owen Jones, seem intended "to convey a sense of pious zeal, or an image of a 'good Muslim'."

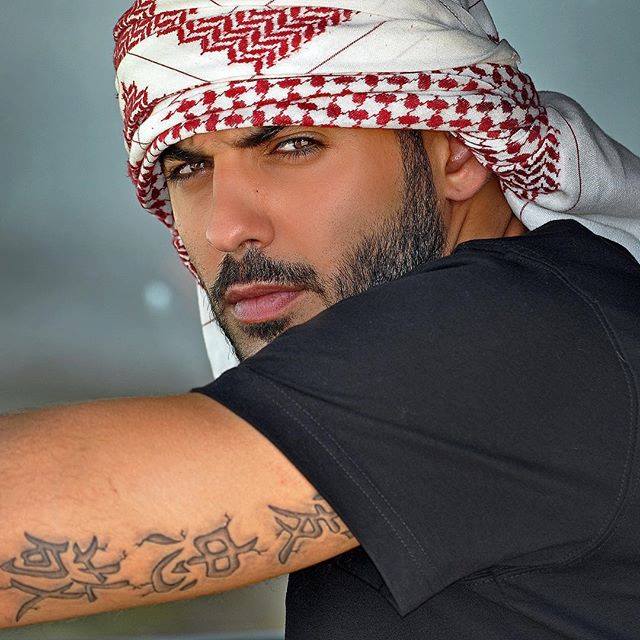

The accompanying profile photos seem to have been plucked at random from the internet. Here, for example, is an account supposedly belonging to someone called Warhan Jamali:

However, a Google image search reveals that the man in the photograph is actually Dr Sami bin Abdullah al-Salih, a Saudi diplomat currently serving as the kingdom's ambassador in Algiers.

Another account, quoting the Prophet in its bio, apparently belongs to a religious gentleman called Mazher al-Jafali but the profile picture comes from the Facebook page of Omar Borkan al-Gala, an Iraqi-born male model who lives in Vancouver. You may remember newspaper stories about him from a few years ago, when he was allegedly thrown out of Saudi Arabia for being "too handsome".

Omar Borkan al-Gala on Facebook

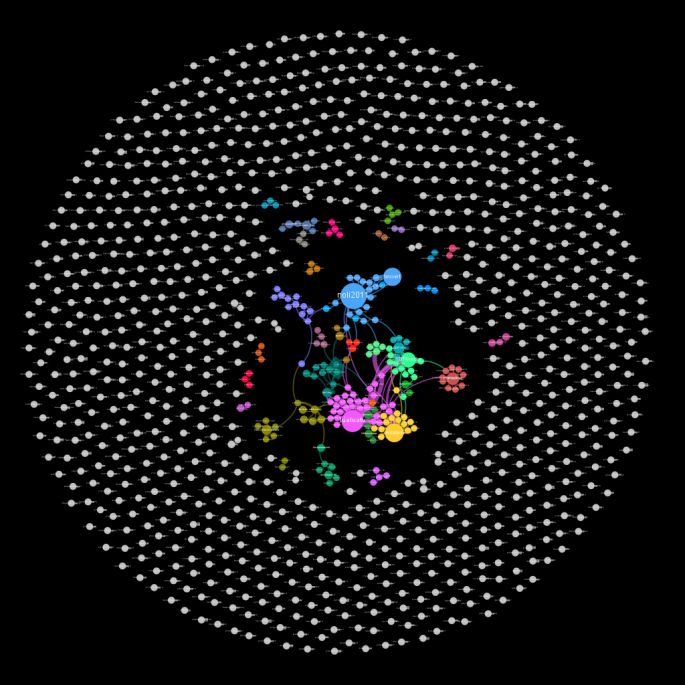

Marc Owen Jones has also produced this visualisation of the #bahrain Twittersphere:

The coloured dots in the centre represent apparently legitimate accounts which interact with each other. The grey dots represent accounts which were not interacting when the snapshot was taken. Some of these may be genuine but Owen Jones believes most of them are robots. He writes:

"While the grey, mostly bot accounts are not engaged, the fact they surround the core community is a good metaphor for how they pollute, or drown out the genuine interactions. The visual strongly shows a grey shield around a core, attempting to make real debate impenetrable."

Posted by Brian Whitaker

Thursday, 23 June 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed