Country narrative: Libya

March 24, 2020

Neither of the two main factions has reported any coronavirus cases but both are taking precautions. The UN-backed Government of National Accord has ordered the closure of restaurants and cafes and banned gatherings for parties, weddings and funerals. On Saturday it imposed a night-time curfew from 6pm to 6am. The Benghazi-based Libyan National Army imposed a similar curfew last Thursday in the areas under its control.

March 25

The UN-backed Government of National Unity (GNA) reported the country's first case – a 73-year-old man who arrived in Libya from Tunisia on March 5, having previously been in Saudi Arabia. He is now being treated in a hospital in Tripoli. The Associated Press reports:

"The confirmation of Libya's first case, three weeks after the patient's arrival in the country, poses a test for its fragile medical system. Attempts at a nationwide disease protection program have been undermined by the country's division between two rival governments, in the east and west of the country, and a patchwork of armed groups supporting either administration.

"Even on Tuesday, Tripoli's suburbs came under heavy fire as the United Nations appealed for a freeze in fighting so authorities could focus on preventing the spread of the coronavirus."

Both of the main warring factions have previously announced measures to reduce the spread of the virus.The GNA ordered the closure of restaurants and cafes and banned gatherings for parties, weddings and funerals. On Saturday it imposed a night-time curfew from 6pm to 6am. The Benghazi-based Libyan National Army imposed a similar curfew last Thursday in the areas under its control. However, according to the National Center for Disease Control, only 61 tests for the virus have so far been carried out.

April 2

The National Center for Disease Control has so far confirmed 10 cases but has only carried out a total of 136 tests. Meanwhile, there are 126 suspected cases and 139 people are in quarantine.

April 6

The National Center for Disease Control has so far confirmed 18 cases but testing is limited. Only 186 tests have been carried out during the last four days, bringing the total to 312 tests.

April 25

So far, Libya has only 61 confirmed cases of Covid-19 but limited capacity for testing means an unknown number of infections are going undetected. At the same time, Libya faces a series of additional problems that make tackling the virus more difficult.

The country is now in its ninth year of internal conflict and, in the words of the UN's Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA), growing levels of insecurity, political fragmentation and weak governance have led to a deterioration of basic services, particularly in the health system.

Earlier this month, heavy shelling hit the 400-bed al-Kahdra hospital in Tripoli which had been earmarked for treating Covid-19 patients. At least 27 health facilities have been damaged in clashes – including 14 that have since been closed.

Despite measures intended to prevent transmission of the virus – such as curfews – contact-tracing and testing are limited and there's a shortage of protective equipment for medical staff.

"Many points of entry, particularly land borders, are not fully secured and don’t have capacity and resources for testing and quarantining," the OCHA says in a recent report.

It adds that locations of healthcare facilities for confirmed and suspected Covid-19 cases often have to be changed because of "resistance from local communities or armed groups" who don't want them in their area.

Libya has 870,000 people categorised by the UN as "people of concern". They include 48,000 registered refugees and asylum seekers, 373,000 internally displaced persons (IDPs) and 448,000 returnees who were previously displaced.

Migrants and refugees in detention are less able to access critical medical care for Covid-19, the OCHA says, and the conditions in detention centres put them at greater risk.

"Many IDPs, and some returnees, live in sub-standard housing, informal settlements or camp-like settings hindering their ability to adopt social distancing measures and limiting access to functional basic services and essential household necessities," the report adds.

A Swiss-based organisation, REACH, has also been looking at the impact of the Covid-19 crisis on vulnerable populations in Libya and has highlighted a series of specific issues:

● Access to information: Migrants and refugees are the least informed about the virus, particularly older people and unaccompanied children. "Much of the key messaging (on television, radio and in print) is in Arabic, which some migrant and refugee communities are unable to understand," the report says. "For unaccompanied children, this issue is compounded by the fact that such messaging is often not presented in an age-appropriate format. Moreover, members of all these groups have less social connections and networks that would enable them to be better informed about the current situation."

Even if they are aware of the advice – such as frequent hand-washing – they may not be in a position to follow it. (An attack on the Man-Made River Project cut off water supplies to more than two million people in the Tripoli area earlier this month, and in the east of the country the UN is distributing 20,000 bars of soap in IDP camps – two bars per person.)

● Access to healthcare: Among black African communities in Libya, fears of discrimination and fears relating to immigration status were cited as barriers to accessing health care. Other difficulties resulted from restrictions on movement (due to the virus) and fear of catching the virus at health facilities.

● Access to education: Schools are closed and although the education ministry has set up distance learning, children in migrant and refugee communities are reported to be no longer receiving any form of education, even remotely.

● Access to work: This is a general problem – many people have lost jobs – but it particularly affects migrants and refugees who tend to rely on casual work or temporary jobs. Restrictions on movement also make it more difficult to search for alternative work. Out of 40 migrants and refugees surveyed, 34 said they has lost work as a result of the Covid-19 restrictions, three said they had already been unemployed and three said they were continuing to work.

May 15

Unidentified militiamen entered the intensive care unit at al-Jala hospital in the Libyan city of Benghazi on Sunday and opened fire. Medical staff escaped with their lives but seven respirators were badly damaged, along with an ultrasound machine and several monitors.

In Libya's internal conflict – now in its ninth year – health facilities often become targets. On Thursday, the 950-bed Central Hospital in Tripoli was damaged by shrapnel when the capital came under shell fire.

So far this year there have been 17 attacks on field hospitals, ambulances, health workers and medical supplies, according to the International Rescue Committee.

All this adds to the difficulties of those struggling to save the country from being overwhelmed by coronavirus.

If official figures are to be believed, though, the virus hasn't firmly taken root. Only three Covid-19 cases have been confirmed so far this month – none of them during the past week.

Since the outbreak began in March the National Center for Disease Control (NCDC) has reported a total of 64 cases. Of those, 28 have since recovered and three have died. However, a joint statement by several UN bodies warned on Wednesday that "the risk of further escalation of the outbreak is very high".

Limited testing capacity raises the possibility of undetected cases, though recent test results have given some reassurance on that point. All of the 711 tests processed during the past week proved negative.

Altogether, only 3,539 tests have been carried out in Libya and when population size is taken into account this puts it in 167th position in the worldwide testing league table.

With support from the WHO, testing capacity is gradually increasing. Two additional Covid-19 labs have been established and two more are being upgraded – which will bring the total to five. The NCDC has distributed 15 GeneXpert machines and several PCR machines.

GeneXpert machines were developed years ago for tuberculosis testing but can be adapted to carry out quick and fully automated tests for Covid-19. However, each test requires a special cartridge – and Libya currently has only 2,500 of those.

The two rival authorities in the east and west of the country have both introduced preventive measures, including night curfews but according to the UN's Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) isolating people who become infected "remains a challenge".

In a report on Tuesday, the OCHA noted that out of 41 people who had Covid-19 at the end of April only two were isolated in hospital. The others all stayed at home, without any monitoring for compliance with the quarantine rules. The OCHA also reported compliance problems among people identified through contact tracing as possibly being infected.

Along with many other countries, Libya has begun repatriating citizens who had become stranded abroad. This inevitably creates more opportunities for the virus to enter the country.

Most of the Libyan returnees are arriving overland or by air from Egypt, Tunisia and Turkey. They are required to be tested before or after arrival and according to the OCHA are then sent into home isolation. There have already been problems with this in Jordan and Lebanon where non-compliance with home isolation has led to multiple new infections.

In the east of the country, however, the rules seem to be stricter and photos posted on Facebook show returnees being accommodated in a hotel in Benghazi under medical supervision.

Truck drivers arriving from Tunisia are also being tested and then quarantined in the border town of Zuwara – which is a major centre for smuggling. Not surprisingly, the OCHA says Zuwara's municipal authorities "have reported that there are a number of trucks entering Libya from Tunisia that are not coordinating with the emergency committee and are not being tested".

June 10

The UN's latest report on the coronavirus situation in Libya makes grim reading. Just about everything that could go wrong is going wrong.

None of it is helped by the ongoing conflict between the UN-backed Government of National Unity (GNA) in Tripoli and Field Marshall Haftar's forces based in the east of the country, plus the existence of numerous lawless militias.

Although Libya's first Covid-19 case was reported back in March, a national plan for dealing with the epidemic has still not been agreed.

"In the absence of a coordinated national response, many municipalities have imposed their own regulations and taken their own measures such as establishing local Covid-19 crisis committees," the UN's Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) says in a report issued on Monday.

Another problem is money. "Specific funds for the Covid-19 response have yet to be released by the Central Bank of Libya," the OCHA says. Health officials in the east, where the situation is described as dire, say they don't expect to receive any.

"Little progress has been made facilitating approvals for the importation of health supplies, the release of salaries and the provision of PPE to health workers," the report adds. Although some supplies have been received, the health ministry in Tripoli has yet to come up with a plan for distributing them.

Libya's health services had already been weakened by the armed conflict before the coronavirus arrived. By March, at least 27 health facilities had been damaged by fighting and 14 of them had closed. In May, unidentified militiamen entered the intensive care unit at a hospital in Benghazi on Sunday and opened fire. Medical staff escaped with their lives but seven respirators were badly damaged, along with an ultrasound machine and several monitors.

Many health workers, especially in the south, are refusing to report for duty because they have no personal protective equipment. Health services are also affected by frequent power cuts and shortages of fuel.Currently, the OCHA says, around 75% of health facilities are not functioning at capacity due to staff shortages, the need for repairs, or inaccessibility because of the security situation.

The OCHA describes Libya's capacity for monitoring disease as "weak". In countries such as Libya, where the routine public health monitoring has broken down, the World Health Organisation supports an alternative early-warning system known as EWARN – a network of "sentinel sites" providing information about what is happening on the ground.

In Libya, though, EWARN appears to be breaking down too. "Weekly EWARN bulletins have stopped and the number of sentinel sites has decreased – from 70% in March to 50% in April," the OCHA says.

The map below, produced by the REACH Resource Centre, is a risk assessment of Libya's various administrative districts. Based on 13 different indicators, such as access to health services, population density, age profile, prevalence of chronic diseases, etc, it ranks them according to their "pre-existing vulnerabilities". This is not a prediction of where outbreaks are likely to occur but it highlights the areas where the effects of Covid-19 are likely to be most severe.

Click here to enlarge. Source: REACH Resource Centre" src="/sites/default/files/libya-vulnerabilities.jpg" style="height:507px; width:500px" />

According to the official figures, only 359 cases of Covid-19 have been confirmed in Libya, along with five related deaths. This probably doesn't reflect the true picture because the level of testing is very low.

Despite uncertainty about the actual figures, the infection rate has clearly been increasing since the end of May and the total of known cases has almost doubled during the past week. Officials attribute this to the return of Libyans who were stranded abroad.

During May, according to reports cited by the OCHA, 4,900 Libyans returned by air, while 4,200 arrived overland from Tunisia and Egypt.

The most infected part of the country, with more than 140 confirmed cases, is in and around Sebha, an oasis city 400 miles south of Tripoli.

July 11

Libya is in its ninth year of internal conflict. The UN-backed Government of National Unity in Tripoli is challenged by Field Marshall Haftar's forces based in the east of the country. There are also numerous militias.

This leaves the country ill-equipped to cope with a major epidemic. Growing levels of insecurity, political fragmentation and weak governance have led to a deterioration of basic services, particularly in the health system. At least 27 health facilities have been damaged or closed by fighting and some have been attacked directly. The number of confirmed infections is still small but testing is very limited. There are 870,000 people – refugees, asylum seekers and displaced persons – who the UN regards as especially vulnerable.

According to the WHO, most Covid-19 cases are centred around Sebha, an oasis city 400 miles south of Tripoli. Sebha is close to the borders with Niger, Chad and Algeria, and is a major hub on the migration route from Africa to Europe. It currently hosts about 40,000 migrants. A Swiss-based organisation, REACH, has issued a detailed report on the situation there.

August 15

The World Health Organisation (WHO) describes the coronavirus situation in Libya as "clusters of cases" – in other words, a series of local outbreaks rather than a generalised epidemic. Sebha, Tripoli, Zliten, Misrata, Ashshatti, Ubari, Traghen, Janzour and Khoms are said to be particular hotspots.

Testing is very limited and the number of confirmed infections is still relatively small but growing fast. Half of the known cases were recorded this month.

Investigations by the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) have concluded that most infections are the result of people not practising social distancing. The Libya Herald reports that most people do not wear masks in public. It adds: "Many still spend the weekend with their parents/relatives, attend funerals, baby-parties, and weddings. And although function halls have been forced to shut down, many are holding events for hundreds in open locations such as farms."

The authorities in Tripoli have responded by announcing series of penalty charges, including fines of 250 dinars ($180) for not wearing a face mask on public transport and 500 dinars (plus temporary closure) for businesses that fail to enforce mask-wearing.

August 29

The World Health Organisation (WHO), which previously described the coronavirus situation in Libya as "clusters of cases", has now revised its status to "community transmission". In other words, the situation has worsened

Investigations by the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) have concluded that most infections are the result of people not practising social distancing.

September 5

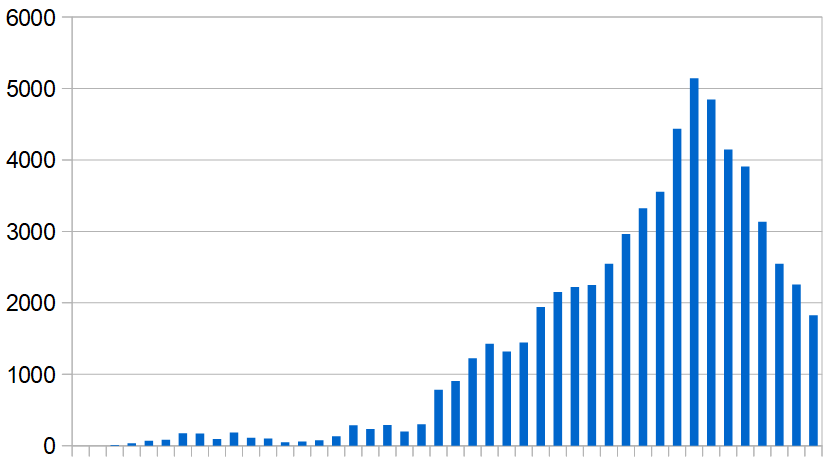

New infections have risen significantly this week, averaging 545 a day compared with 358 the week before, according to official figures.

September 19

According to the official figures Libya's outbreak is still relatively small but the total of confirmed Covid-19 cases has more than doubled over the last three weeks. New infections recorded this week averaged 647 a day.

A UN report issued this week said:

"Persistent and acute shortages in Covid-19 testing capabilities and supplies, along with adequate health care facilities and contact tracing means the true scale of the pandemic in Libya is likely to be much higher ...

"Increasing numbers of health care staff are contracting Covid-19 due to a lack of personal protective equipment."

The report also hinted at a lack of coordination between the ministries of health and the National Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) and called for a clearer understanding of "where and how Covid-19 funds announced by Libyan authorities have been spent".

October 3

In an update this week, the WHO commented: "While Covid-19 is spreading fast and numbers of confirmed patients are rising, there seems to be a lack transparency and communication to the people by the Libyan government."

Growing levels of insecurity, political fragmentation and weak governance have led to a deterioration of basic services, particularly in the health system. At least 28 health facilities have been damaged or closed by fighting and some have been attacked directly. According to the WHO, Dr Abdel-Moneim al-Ghadamsi, professor of surgery at Al-Khadra Hospital, was kidnapped ion 11 September. Another doctor, the only anaesthetic specialist in al-Mogrif Hospital's intensive care unit was attacked on 12 September by security personnel and resigned, leaving the hospital without intensive care services. Bani Walid General Hospital was closed on 8 September after the administrative building and the emergency department were vandalised and staff were attacked.

New infections this week averaged 632 a day, according to official figures. A recent UN report said the true scale of Libya's outbreak is likely to be much higher than the official figures indicate, partly because of low testing capacity and lack of contact tracing.

November 1

Official figures show new Covid-19 infections averaging 960 a day during the past week but the true scale of Libya's outbreak is likely to be much higher. A recent report from the UN's Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) said:

November 18

Update on vaccines: Libya is planning to obtain vaccines through the Covax facility. It has signed an agreement and made an advance payment.

The Libya Observer reports that a budget of $9.6 million has been allocated, though it's unclear whether this includes the cost of distributing and administering the vaccine inside the country.

Given the continuing turmoil in Libya, the World Health Organisation appears to have some concern about the authorities' ability to manage a vaccination programme effectively. In a report last month the WHO said it is supporting them in preparing guidelines and a "readiness assessment tool".

February 6, 2021

Update on vaccines: Libya has ordered 2.8 million doses through Covax but delivery may be four months away.

The National Centre for Disease Control has ruled out use of the Pfizer/BioNTech vaccine because the ultra-cold storage it requires is not available in Libya.

Given the continuing turmoil in Libya, the World Health Organisation has previously expressed concern about the authorities' ability to manage a vaccination programme effectively.