When Saudi Arabia's Haramain railway opened in 2018 it was hailed as a triumph of technology and engineering. The 450-km line linking the holy cities of Mecca and Medina was designed to carry passengers at 350 km an hour. It took 10 years to build and cost more than $16 billion. A year after its opening, though, disaster struck and the line was shut down when fire devastated one of the stations on the route.

The blaze, in Jeddah, swept across the station's roof, dropping smouldering debris on to the concourse below. Firefighters took around 12 hours to bring it under control. Fortunately, no deaths were reported though several people were injured.

It soon became clear that repairs would take a long time, so in order to reopen the railway a new 1.5 km section of track was hastily constructed, bypassing the damaged station. After a brief reopening train services were suspended again because of the Coronavirus pandemic and it was a further year before operation resumed.

The Jeddah station is still out of service but photos posted on Twitter show the replacement roof – with a different construction method – is nearing completion.

The original roof covering consisted of fibre-reinforced plastic (FRP) panels which burned fiercely and emitted huge clouds of black smoke. One question this raises is why a station supposedly built according to the highest and most modern standards had been fitted with a flammable roof.

Immediately after the fire the Saudi authorities promised a full investigation but the outcome is still unknown.

Who will pay?

In February transport minister Saleh al-Jasser said repairs to the Jeddah station will be paid for by "the contractor". Exactly where the money will come from is still unclear, though.

The original contractor for the Jeddah station was Saudi Oger, headed by Lebanese politician Saad Hariri, but it never completed the job. Saudi Oger ran into financial trouble, stopped paying thousands of its workers and eventually went bankrupt owing more than $10 billion. A Turkish firm, Yapı Merkezi, was then called in to finish the work.

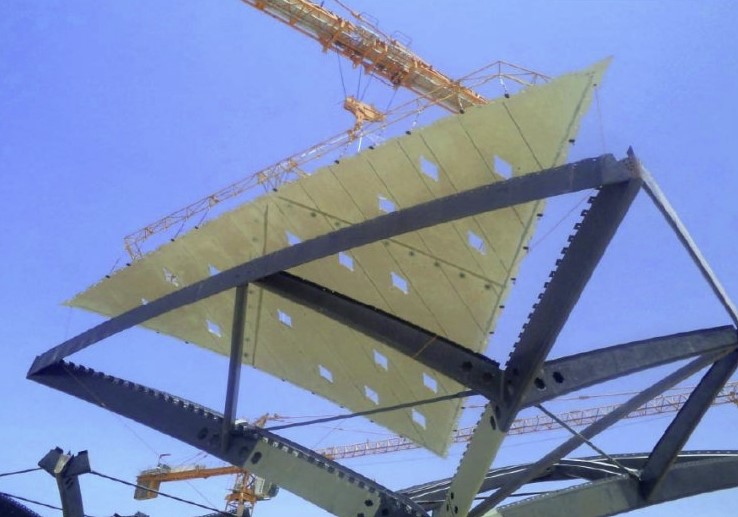

All five stations on the Haramain line are of a similar design with similar roof panels – which raises the possibiity that they are also a fire hazard. However, the panels used in Jeddah may not have been exactly the same as others, because instead of buying them from a specialised manufacturer Hariri's Saudi Oger company decided to make them itself.

There was an account of this in the March 2104 issue of Shape magazine (pages 22-23) which described it as "quite a unique approach". Saudi Oger's project manager for composites, Souhail Alla, told the magazine:

"Rather than contracting the manufacture of the composite roof panels out, we decided to bring this key manufacturing process in-house, as we believe there is great future for composites in architecture."

To that end, they set up new a production facility in Jeddah specially to manufacture the roof panels. This was "quite a big challenge", the magazine said, because "many process aspects called for first-time innovative answers". It meant developing special machinery and equipment – all of it produced in-house by Saudi Oger.

According to the magazine, the panels were "fire retardant". Some technical help was provided by a French company, Méca, though it appears to have been mainly concerned with ensuring the panels were strong enough. Méca's website said the fire specification was ASTM E84 (which checks for surface burning), with a flame index below 250 and a smoke index below 450, but it gave no details about actual testing.

|

The Jeddah station was not Saudi Oger's first venture into the composites business. It had previously constructed a very large dome for the Princess Nourah University in Riyadh.

Combustible panels have also been involved in several fires in the UAE. One broke out at a 63-storey hotel and residential complex in Dubai on New Year's Eve in 2016. Everyone escaped but there were bizarre scenes as cheering crowds and a fireworks display greeted the New Year while smoke and flames billowed from the skyscraper nearby.

In Britain, 72 people died at Grenfell Tower, a 24-storey apartment block, when fire spread through external cladding panels in 2017. Numerous other blocks were found to have similar panels and there are continuing arguments about who should cover the cost of replacing them.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed