Peter Hitchens and an imaginary battle over chemical weapons reports

Blog post, 19 September 2018: Peter Hitchens, the Mail On Sunday columnist, claims to have detected a "very interesting pattern" in official reports about chemical weapon allegations in Syria. The pattern, he says, is that "if official reports don't justify punitive attacks on Syria, new reports then appear, which do provide such justification".

This has now happened twice, he adds – first in connection with Khan Sheikhoun last year and again in connection with Douma earlier this year. On both occasions western powers launched airstrikes in response to claims that the Assad regime had used chemical weapons.

The events in Khan Sheikhoun and Douma have also been the subject of reports by international bodies – more than one such body in both cases. Hitchens describes these as "rival" reports, with the suggestion that since the first report failed to say what "warmongers" were hoping to hear, a second one was obtained to give them a more favourable answer.

Interesting as that theory might be, the evidence doesn't support it. It's based on a misunderstanding of the processes that led to the reports being produced.

The Khan Sheikhoun reports

In the case of Khan Sheikhoun, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) was involved in both of the supposedly competing reports. One came from the OPCW's Fact-Finding Mission (FFM) and the other from the Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM) in which the UN and OPCW were partners.

The main conclusion of the FFM report, issued in June last year, was that a noxious chemical had been released in Khan Sheikhoun, and that "such a release can only be determined as the use of the Schedule 1A(1) chemical sarin, as a chemical weapon".

Four months later, the JIM report said the sarin in question was "most likely" to have been made using a precursor from the Assad regime's original stockpile, and it was "confident" the regime had been responsible for its release in Khan Sheikhoun.

According to Hitchens, the earlier report "was not an adequate basis for military action"; the JIM "then re-examined the case, and claimed that it did justify military action". (For what it's worth, the JIM made no such claim – that wasn't part of its remit – and in any case the relevant military action had already been taken long before either report appeared.)

The fact that the JIM's findings went further than those of the FFM's report was not, as Hitchens seems to think, a sign that they were competing reports. They were complementary and had been assigned different tasks.

The role of the FFM was to establish whether a chemical attack had taken place but its mandate prevented it from investigating who might be to blame.

The purpose of the JIM, on the other hand, was "to identify, to the greatest extent feasible, individuals, entities, groups or governments who were perpetrators, organisers, sponsors or otherwise involved in the use of chemicals as weapons" in Syria.

The Douma reports

Similarly in the case of Douma, western powers carried out punitive strikes (apparently based on their own intelligence assessments) without waiting for investigative reports from international bodies to provide them with a justification.

In July, the FFM issued a progress report on its Douma investigation. It described what the investigators had been doing in Syria and reported the results of laboratory tests on some of the chemical samples collected. They found no evidence that sarin had been used but hinted at the possible use of chlorine. The report made clear that the investigation is continuing, so we shall have to wait for a further report to find out its conclusions.

Douma featured again – briefly – in a report released last week by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria. The Commission, established shortly after the war began, works under the auspices of the UN Human Rights Council. It issues periodic reports in line with its brief "to investigate all alleged violations of international human rights law" in Syria since March 2011. Its brief also says it should try to identify those responsible for violations, with a view to holding them accountable.

The Commission's latest report, a 24-page document, is mostly a review of the the war's impact on civilians during the first half of this year but it also has a section headed "Ongoing Investigations" which includes a couple of paragraphs on Douma. Part of it says:

"Throughout 7 April, numerous aerial attacks were carried out in Douma, striking various residential areas. A vast body of evidence collected by the Commission suggests that, at approximately 7.30 pm, a gas cylinder containing a chlorine payload delivered by helicopter struck a multi-storey residential apartment building located approximately 100 metres south-west of Shohada Square."

This, Hitchens says, has more appeal to "the warmongers' choir" than the preliminary report from the FFM. "Its wording appears to suit them better, just as the JIM report on Khan Sheikhoun appeared to suit them better."

His claim, though, is not only that the Commission's report suited the warmongers but that this was its intended purpose. In the words of the headline on his article: "Have your Experts come up with the Wrong Answer? Well, then, find some other experts."

The trouble with that idea is that there's no "wrong answer" from the FFM for the Commission to correct. The FFM hasn't yet published any conclusions; nothing in its preliminary report conflicts with what the Commission is saying and, conversely, nothing in the Commission's report conflicts with anything the FFM has said so far.

Propaganda line

Fanciful as Hitchens' claims might be, they are also troubling because he seems to have swallowed the line propagated by the Assad regime and Russia that the chemical weapons issue has been cooked up to justify military action. He talks of an "incessant campaign to justify a full-scale US military involvement" in Syria and says that war, these days, "has to be fought by pretext".

But if the US is really itching to get its military deeply involved in Syria we have to ask why it hasn't done so already. There has been no shortage of atrocities that might be used as an excuse – so what, exactly, are the Americans waiting for?

The "pretext" meme regarding western intervention in Syria has been running for more than five years and and it has now worn so thin that Hitchens and others really should know better than to keep repeating it.

Syria chemical attacks: Russia fails in move to obstruct investigation

Blog post, 21 November 2018: A Russian-led move to restrict investigation of chemical attacks in Syria was heavily defeated at the Chemical Weapons Convention review conference in The Hague on Tuesday.

As a result, the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) will now be able to carry out further investigations aimed at determining who was responsible for the attacks.

A team of 10-12 investigators, supported by experts and chemical inspectors already employed at the OPCW, is expected to start work early next year. Extra money has been allocated for this purpose in the organisation's 2019 budget and, according to Russian reports, the amount is $2.4 million.

Since 2014 the OPCW's Fact-Finding Mission has issued numerous reports on alleged chemical attacks in Syria but its mandate was only to establish what happened, and not to apportion blame.

In 2015, in an effort to remedy that omission, the UN Security Council established a special UN/OPCW body known as the Joint Investigative Mechanism (JIM). The JIM had instructions to "identify to the greatest extent feasible individuals, entities, groups, or governments who were perpetrators, organisers, sponsors or otherwise involved in the use of chemicals as weapons, including chlorine or any other toxic chemical, in the Syrian Arab Republic".

Last year the JIM issued a report blaming Syrian government forces for a sarin attack in Khan Sheikhoun. It also decided ISIS fighters were responsible for an attack in Umm Hawsh involving sulfur mustard. The JIM had been proposing to report on other attacks too but Syria and Russia were unhappy with its activities and Russia eventually shut it down by vetoing the Security Council's renewal of its mandate.

This prompted other countries to look for alternative ways of continuing the investigation. In June this year a special session of states parties to the Chemical Weapons Convention overwhelmingly approved a British proposal to change the OPCW's mandate, allowing it to identify those responsible for attacks. The change needed a two-thirds majority to pass but despite opposition from Syria and obstructive tactics from Russia and Iran, 82 countries voted in favour and only 24 against.

While the vote in June gave the OPCW power to attribute blame it did not provide a mechanism for doing so – and that, basically, was what yesterday's wrangling in The Hague was about.

A proposal by Russia and China apparently aimed at obstructing the creation of an "attribution mecahanism" was resoundingly defeated by 82 votes to 30, with 31 abstentions.

The countries supporting Russia and China in the vote were Algeria, Angola, Armenia, Belarus, Bolivia, Burundi, Comoros, Congo, Cuba, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, India, Iran, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Lao, Mozambique, Myanmar, Nicaragua, Pakistan, Palestine, South Africa, Sudan, Syria, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Venezuela, Vietnam and Zimbabwe.

The 2019 budget – including extra money for the investigative work – was eventually approved by 99 votes to 27 after a series of amendments put forward by Russia and Iran had been defeated. A detailed account of the meeting can be found here.

OPCW's Douma investigation points to gas cylinders dropped from the air

Blog post, 2 March 2019: On Friday the OPCW's fact-finding mission issued its final report on alleged chemical attacks in the rebel-held Syrian town of Douma last April.

Dozens of people were reportedly killed by a release of toxic chemicals and the US, Britain and France responded shortly afterwards with airstrikes targeting the Assad regime's chemical facilities.

Although the regime was widely believed to have used chemical weapons in Douma, the regime – together with its chief ally, Russia, and various western conspiracy theorists – claimed rebels had faked the attacks in order to blame the regime.

In an interim report last July, the OPCW said laboratory tests had found no evidence that sarin or a similar nerve agent had been used but found possible evidence of chlorine use.

There is substantial evidence that chlorine has been used as a weapon elsewhere in Syria during the conflict. According to a previous OPCW report it was used “systematically and repeatedly” as a weapon on villages in northern Syria.

The 106-page report issued on Friday points to two main conclusions regarding Douma – that the chemical involved was chlorine and that the gas came from cylinders which had been dropped from the air.

The significance of this – although the report doesn't spell it out – is that the cylinders must have been dropped by pro-Assad forces, since the rebel fighters had no aircraft.

Based on all the available evidence, including witness testimony, environmental and biomedical samples and toxicological and ballistic analyses, the report says there are "reasonable grounds" for believing a toxic chemical was used as a weapon, and it adds: "This toxic chemical contained reactive chlorine. The toxic chemical was likely molecular chlorine."

On the question of delivery methods, the report looks in detail at two yellow cylinders found in Douma. It describes these as "industrial cylinders dedicated for pressurised gas" about 140cm long and 40cm in diameter.

One cylinder was found lying on a top-floor patio where its impact had apparently punched a hole through into a room below. The other cylinder had apparently crashed through a roof into a bedroom, ending up on the bed.

video here)" src="/sites/default/files/douma-balcony.jpg" style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; height:288px; width:500px" />

video here)" src="/sites/default/files/douma-bedroom.jpg" style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; height:335px; width:500px" />

Images of the two cylinders were circulated on the internet shortly after the attack. Assad's supporters claimed they had been planted by rebels rather than falling from the sky and suggested the roof damage seen in the images must have had a different cause.

However, the OPCW's report dismisses that idea. It says:

"The team analysed the available material and consulted independent experts in mechanical engineering, ballistics and metallurgy who utilised specialised computer modelling techniques to provide qualified and competent assessments of the trajectory and damage to the cylinders ...

"The analyses indicated that the structural damage to the rebar-reinforced concrete terrace at Location 2 [the top-floor patio] was caused by an impacting object with a geometrically symmetric shape and sufficient kinetic energy to cause the observed damage. The analyses indicate that the damage observed on the cylinder found on the roof-top terrace, the aperture, the balcony, the surrounding rooms, the rooms underneath and the structure above, is consistent with the creation of the aperture observed in the terrace by the cylinder found in that location.

"At Location 4 [the bedroom], the results of the studies indicated that the shape of the aperture produced in the modulation matched the shape and damage observed by the team. The studies further indicated that, after passing through the ceiling and impacting the floor at lower speed, the cylinder continued an altered trajectory, until reaching the position in which it was found."

Widely-circulated images show that both cylinders had been fitted with a metal harness to provide them with wheels, lugs for lifting, and tail fins. The addition of tail fins is especially important because, according to a previous OPCW report, this shows the cylinders were intended to be dropped from a height, with the fins stabilising their descent. In other words, the fins confirm they had been adapted for use as a weapon.

The same OPCW report also said that if weapons dropped from the sky were "not designed to cause mechanical injury through explosive force" it was reasonable to conclude that they were chemical weapons – and this is clearly the case with the Douma cylinders.

The fact-finding mission's mandate is to determine whether chemical weapons or toxic chemicals as weapons have been used in Syria, and this does not include identifying who is responsible for alleged attacks. However, as a result of a decision last June the OPCW itself is authorised to identify those responsible and is likely to address that at a later stage.

How a yellow cylinder became a propaganda weapon in Syria

here." src="/sites/default/files/ru-cyl-4.jpg" style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; height:322px; width:550px" />

Blog post, 17 March 2019: A recent report by the chemical weapons watchdog, OPCW, has caused a flurry of activity among defenders of the Assad regime who claim chemical attacks in Syria have been faked or staged by rebels.

The obvious conclusion to be drawn from the OPCW report was that two cylinders of chlorine gas had been dropped from the air on the town of Douma last April – in which case it’s clear they were dropped by pro-Assad forces, since the rebels had no aircraft.

Undaunted by that, Syria “truthers” turned their attention to a third cylinder which was also mentioned in the report. Although OPCW investigators found no evidence linking it to chemical weapons, the regime’s defenders claim otherwise and have turned its discovery into a propaganda weapon.

While the truthers’ insistence that this third cylinder was part of a “false flag” plot by rebels to discredit the regime bears little scrutiny it’s a prime example of the way snippets of information can be manipulated to cast doubt on mainstream explanations of events in Syria.

Unidentified chemicals

Once chemical weapons became an issue in the conflict the Assad regime and its allies began publicising various discoveries of “chemicals” and “laboratories” in rebel hands. The main purpose of reporting these discoveries was to suggest that rebel forces were manufacturing chemical weapons for use in “false flag” attacks.

Last year, for example, Vanessa Beeley, a prominent defender of the regime, visited what she claimed – without evidence – was a rebel “chemical weapons facility” captured by government forces.

In her report for the conspiracy-theory website 21st Century Wire, she described seeing numerous sacks and containers but her military escorts said some of them were booby-trapped, so she couldn’t examine them closely. The only “chemical” she clearly identified was RDX, a common type of explosive, though her article included a series of photos showing unidentified substances that it claimed were “chemical weapon ingredients”.

A Russian ‘discovery’

On 17 April – ten days after the Douma attacks and three days after the US, Britain and France launched reprisal strikes against the regime – Russia announced that its troops had made a new discovery in the Douma area. TASS news agency described it as “a militants’ lab for the production of chemical weapons and the storage of its components”, while Sputnik News talked of “a warehouse of substances necessary for the production of chemical weapons”. Videos circulated by Russian media showed various items in the basement of a war-damaged apartment block, including a large yellow cylinder possibly containing chlorine gas.

At Syria’s request, the OPCW agreed to visit the site and concluded that the Russian claim was false. While it found chemicals “consistent with the production of explosives and propellants” there was no sign of “any major key precursors” for chemical weapon production.

However that didn’t explain the yellow cylinder which, according to Russia and Syria, contained chlorine. Its contents have not been confirmed by the OPCW whose investigators decided it would be too hazardous to tamper with the cylinder’s valve in order to obtain a sample. Nevertheless, it’s likely that the cylinder did contain chlorine (or had done so in the past). Gas cylinders are normally colour-coded and, although coding systems vary, yellow commonly indicates chlorine.

The question this raises is why a cylinder of chlorine gas – if that’s what it was – would be stored in a makeshift explosives factory because, as the OPCW noted, it was not relevant to manufacturing explosives. Equally, though, the investigators found no evidence of an intention to use it as a chemical weapon. Chlorine is a common substance with multiple civilian uses, including the purification of water.

When a chemical becomes a weapon

Under the Chemical Weapons Convention, any toxic chemical can potentially become a chemical weapon. The test is whether it has been “specifically designed to cause death or other harm” through its toxic properties.

Unlike the cylinder seen in the rebel explosives factory, the two cylinders implicated in the Douma attacks had been specially adapted for use as weapons. They had been fitted inside a metal frame to provide wheels, lugs for lifting, and tail fins.

The addition of fins is especially significant because, according to a previous OPCW report, it shows the adapted cylinders were meant to be dropped from a height, with the fins stabilising their descent. The same OPCW report also said it was reasonable to conclude that cylinders adapted in this way were chemical weapons since they were “not designed to cause mechanical injury through explosive force”.

On that basis, the “rebel” cylinder can’t be considered as a chemical weapon because, in the words of the OPCW investigators, it was “in its original state and had not been altered”. The investigators also noted “differences” in this cylinder compared with the two implicated in the Douma attacks, but gave no details.

Twitter activity

Inconvenient as this was for the regime’s defenders, they were not to be put off by the investigators’ findings. Despite the OPCW’s mention of differences, in postings on Twitter the “rebel” cylinder became “nearly identical” to the other two:

… and …

Another Twitter user, Ian Wilkie, who has a history of spreading false information about Syria (see here and here), even dispensed with the word “nearly”:

The three who posted these tweets – Partisangirl, Tony Cartalucci and Wilkie – are all regular promoters of “alternative” narratives about Syria, and by presenting the third cylinder as “identical” or “nearly identical” to the other two they were implying a connection that could not be justified by the evidence.

The key difference was that the third cylinder had not been adapted for use as a weapon. For what it’s worth, the third cylinder was also of a different type. Unlike the two weaponised cylinders, it had a second outlet sealed with a metal nut adjacent to the main valve.

This can be seen as a small protrusion in the OPCW’s photo of the cylinder though it’s partly obscured behind the main valve. There are other photos on Twitter that show it more clearly.

There was no such outlet on the two weaponised cylinders, as can be seen from other photos in the OPCW report:

Meanwhile, in an article for 21st Century Wire, Cartalucci acknowledged that the “rebel” cylinder had not been adapted like the other two but wrote:

“The obvious implications of a nearly identical canister turning up in a militant workshop making weapons is that the militants may likely have also made the two converted canisters found at locations 2 and 4 [where the chemical attacks are reported to have occurred].”

In the absence of any evidence that rebels were making the metal frames that turned ordinary gas cylinders into chemical weapons it’s difficult to see how Cartalucci could reach that conclusion, but he continued:

“The presence of a canister nearly identical to those found at locations 2 and 4 in a militant weapons workshop provides at least as much evidence that militants staged the supposed chemical attack as the Western media claims the canisters at locations 2 and 4 suggest it was the Syrian government.” [Italics added.]

This is a ridiculous claim but it’s par for the course. While the truthers are ultra-sceptical about evidence from western sources and international bodies such as the UN and OPCW, they seem happy to trust the Assad regime and its allies.

Thus, in his article for 21st Century Wire, Cartalucci dismisses the OPCW report on Douma as “too ambiguous to draw a conclusion” and, in an article for Global Research (another conspiracy-theory website) he complains that some munition fragments passed to the OPCW for testing “lacked a chain of custody, negating its probative value”.

Oddly, though, he shows no interest in questioning the “rebel” cylinder’s chain of custody. How can we be sure that the cylinder was in the basement store when rebels abandoned it and was not placed there later after the Russian troops arrived?

Five years on, inspectors still doubt that Syria has disclosed all its chemical weapons

Blog post, 9 May 2019: More than five years after Assad regime said it was renouncing chemical weapons, international inspectors are still unable to verify that it has really done so.

Syria joined the Chemical Weapons Convention under international pressure in 2013 following a nerve agent attack in Ghouta that killed hundreds of people – and by joining the convention committed itself to chemical disarmament. It was required to declare all its stocks and related production facilities, which would then be destroyed or dismantled under supervision of the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

All chemicals declared by the regime were removed from Syria in 2014 and destroyed. The OPCW also verified the destruction of all 27 chemical weapons production facilities declared by the regime.

The word "declared" is important here because the initial declaration – as the regime later acknowledged – was incomplete. During the last few years numerous amendments have been made to the original document in the light of inspectors' discoveries and the OPCW has still not accepted the revised declaration as complete. There remain "gaps, inconsistencies and discrepancies" (to use the official phrase).

Syria initially declared four different chemical warfare agents but, following "consultations" with the OPCW, it added a fifth to the list. Later, tests on samples obtained by inspectors in Syria "indicated potentially declarable activities involving five additional chemical agents" and more "consultations" ensued.

Seeking explanations

Almost three years after the start of this process, the OPCW reported that there were still four chemical agents detected through sampling whose presence the regime had "not yet adequately explained".

There were also discrepancies between Syria's records of chemical weapons production and the quantities it had declared. The OPCW said it was "unable to verify the precise quantity of chemical weapons that were destroyed or consumed" before Syria signed up to the convention. At one point the regime claimed it had used 15 tonnes of nerve agent and 70 tonnes of sulfur mustard for research – figures that the inspectors found hard to believe since only tiny amounts would be needed for research.

On the munitions front, there were difficulties accounting for 2,000 or more chemical shells which Syria said it had either used or destroyed – after purportedly adapting them for non-chemical purposes. Again, the inspectors doubted the truth of this because converting the shells into conventional weapons would scarcely have been justified by the effort and expense.

While some of these problems might be attributed to poor record-keeping or Syrian unfamiliarity with the precise requirements of the Chemical Weapons Convention, the regime's general approach has not been suggestive of sincere intentions.

Inspections hampered

Inspectors working on the ground in Syria faced various difficulties which which cumulatively gave the impression of intentionally hampering investigations. According to a Reuters report, these have included "withholding visas, submitting large volumes of documents multiple times to bog down the process" and last-minute restrictions on site inspections.

Inspectors have also had difficulty gaining access to the most relevant Syrian officials – those with "strategic knowledge and oversight" of the chemical weapons programme.

In April last year the OPCW sent Syria a list of "unanswered questions" – to which Syria replied three months later. After studying the reply, the OPCW concluded that it didn't really tell them anything new.

Summarising the position last July, the OPCW said:

"While the Syrian Arab Republic has remained engaged with the Secretariat in efforts to clarify outstanding issues, the nature and substance of the information that has been provided to the Secretariat do not enable it to resolve all identified gaps, inconsistencies, or discrepancies in the declaration."

It added that the number of unresolved issues had grown rather than decreased and "the Secretariat therefore remains unable to state that the Syrian Arab Republic has submitted a declaration that can be considered accurate and complete".

New construction work

Towards the end of last year inspectors visited the Barzah and Jamrayah branches of the Scientific Studies and Research Centre (which carried out chemical weapons research, among othe things) and found "ongoing construction activities" at both sites. The building work at Barzah was especially interesting because it had been targeted by US-led airstrikes the previous April in response to the reported chemical attack on Douma. The OPCW "advised" Syria that in future it should be notified about "the nature and scope" of any such activity before construction began – and Syria reportedly agreed.

Since then, there have been renewed efforts "to clarify all outstanding issues" relating to Syria's 2013 declaration. Meetings were held in Lebanon in February and at The Hague in March to map out a way forward.

However, this is unlikely to put an end to the wrangling any time soon. Last month, inspectors made five visits to the sites of former chemical weapons production facilities and collected 33 samples. The results of laboratory tests are still awaited.

This was not routine sampling and it suggests the OPCW had suspicions of illicit activity. Previous sampling of this kind, in 2014, revealed several undeclared chemical site, plus evidence that the regime had been working on soman – a nerve agent not mentioned in its initial declaration.

'Incidents' under investigation

Meanwhile, the OPCW's Fact-Finding Mission is investigating five reported chemical "incidents" from 2017. These are:

- Kharbit Masasnah on 7 July 2017 and 4 August 2017

- Qalib Al-Thawr, Al-Salamiyah, on 9 August 2017

- Yarmouk, Damascus, on 22 October 2017

- Al-Balil, Souran, on 8 November 2017

These don't appear to have been reported in the media at the time and it's unclear why the OPCW is interested in them now. However, this latest investigation is taking place under new rules – introduced last June – which allow the OPCW to apportion blame for chemical attacks. Previously, its role was limited to establishing what happened.

If the Fact-Finding Mission concludes that chemical weapons were used, or are likely to have been used, the new Investigation and Identification Team will then step in and try to find out who was responsible.

Leaked document revives controversy over Syria chemical attacks

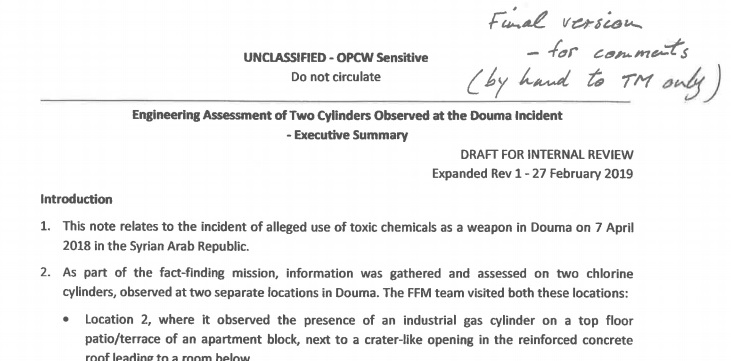

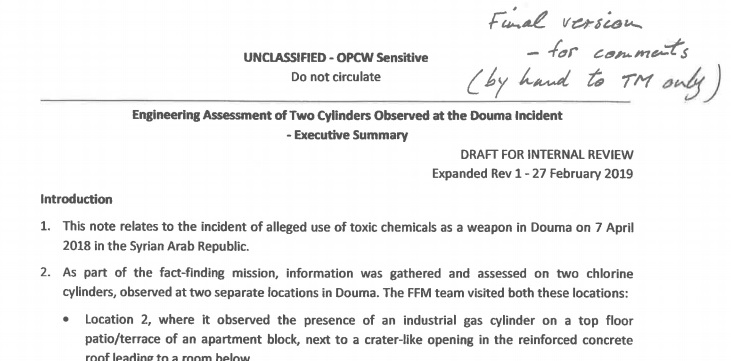

Blog post, 16 May 2019: A leaked document which contradicts key findings of an official investigation into chemical weapons in Syria has surfaced on the internet. Described as an "engineering assessment" and marked "draft for internal review", it appears to have been written by an employee of the Organisation for Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) – the international body charged with the investigation.

In April 2018 dozens of people were reportedly killed by a chemical attack in Douma, on the outskirts of Damascus, and western powers responded with airstrikes directed against the Assad regime.

In March this year, after a lengthy investigation, the OPCW issued a report which found "reasonable grounds" for believing a toxic chemical had been used as a weapon in Douma and suggested the chemical involved was chlorine gas, delivered by cylinders dropped from the air.

Although the investigators' brief did not allow them to apportion blame, use of air-dropped cylinders implied the regime was responsible, since rebel fighters in Syria had no aircraft.

The 15-page leaked document takes the opposite view and says it is more likely that the two cylinders in question had been "manually placed" in the spot where they were found, rather than being dropped from the air. The implication of this is that Syrian rebels had planted them to create the false appearance of a chemical attack by the regime.

The document has caused excitement on social media among those who see it as discrediting the OPCW's official investigation. It was posted on the internet by the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media which not only defends the Assad regime against accusations of using chemical weapons but also disputes Russia's use of a nerve agent against Sergei and Yulia Skripal in Britain last year (see previous blog posts).

Who is Ian Henderson?

The document appears to be genuine and purports to have been written by Ian Henderson, a man whose connections with the OPCW stretch back more than 20 years.

The OPCW was established in 1997 and during its first year of operation Henderson, originally from South Africa, was one of 13 people appointed as its first "P-5 level inspection team leaders".

It's not clear, though, that Henderson has worked for the OPCW continuously since then. The OPCW regards itself as a "non-career" organisation. It doesn't like employees to stay for more than seven years and consequently hires most of them on fixed-term contracts.

Around 2014 Henderson is understood to have been working for the OPCW as a consultant on Syria, and later on contingency planning.

In February last year, about six weeks before the Douma incident, a "Temporary Working Group" set up by the OPCW's Scientific Advisory Board met for the first time. A published account of the meeting shows that Henderson – who it described as a OPCW Inspection Team Leader – gave a talk about contingency planning for Challenge Inspections (CI) and Rapid Response and Assistance Missions (RRAM). A training exercise for RRAMs had taken place in Romania the previous December.

The exact nature of Henderson's involvement in the Douma investigation is still unclear ... and a matter of dispute.

The leaked document presents its findings as an assessment by "the engineering sub-team" under Henderson's leadership. In a commentary on the document, the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media says the engineering sub-team carried out "on-site inspections in April-May 2018" and that Henderson was "the engineering expert on the FFM" (the officially-designated Fact-Finding Mission).

However, the Working Group says that when it contacted the OPCW's press office it was told “the individual mentioned in the document [i.e. Henderson] has never been a member of the FFM”. The Working Group adds: "This statement is false."

Whether Henderson was formally a member of the Fact-Finding Mission (or not) is an important question because it affects the status of the document he produced. If he wasn't a recognised FFM member, this could help explain why the document's findings were ignored in the official report.

Access to data

Whatever his actual position, though, it's clear that the "engineering assessment" in the leaked document was carried out with the OPCW's blessing, since Henderson's team had been given access to data compiled by the Fact-Finding Mission. The document says: "The studies on the two cylinders were conducted using sources of information available to the FFM team." It also makes clear that Henderson was allowed to consult experts outside the OPCW.

But why, if he was not a member of the FFM team, would his OPCW bosses have let him do that? It does look rather odd.

One story circulating in the chemical weapons community (though not confirmed) is that Henderson had wanted to join the FFM and got rebuffed but was then given permission to do some investigating on the sidelines of the FFM. The suggestion (again, not confirmed) is that this was a way of extending his contract at the OPCW. If true, it might explain how he appeared to be working with the FFM while not (according to the OPCW press office) actually being part of it.

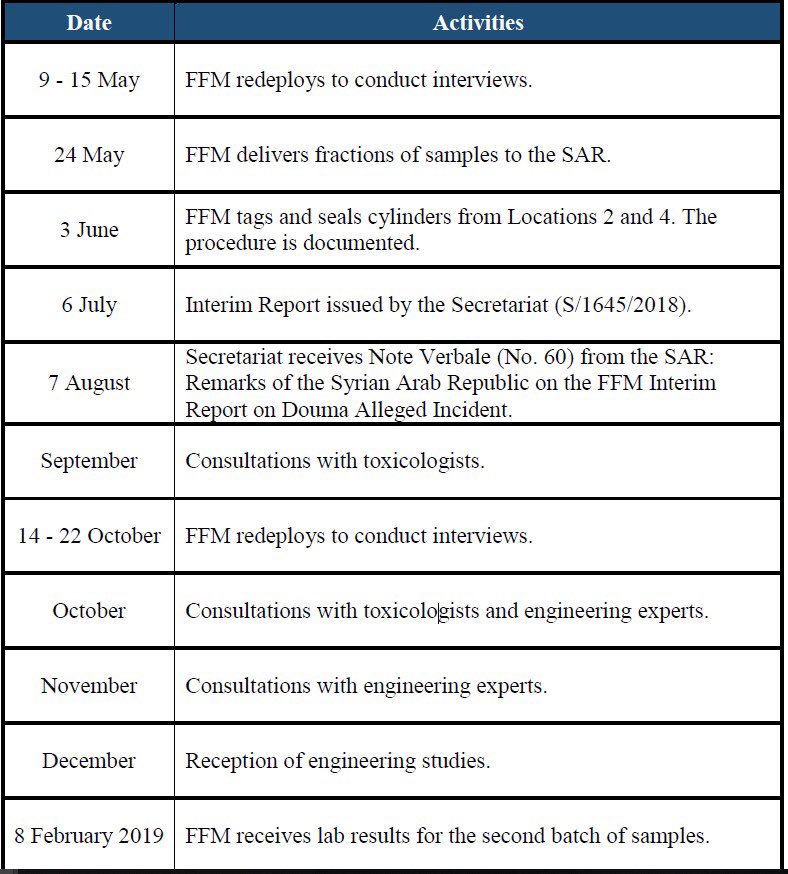

In a preliminary report on Douma last July, the FFM said further work was needed in connection with the two cylinders and the related damage: "A comprehensive analysis by experts in the relevant fields will be required to provide a competent assessment of the relative damage."

The experts' analysis – indicating that the cylinders could have been dropped from the air – was eventually presented in the FFM's final report, published on 1 March.

On 27 February – just two days before the final FFM report was published – Henderson handed in his own report offering contrary conclusions.

Exactly how the FFM reacted on receiving it at such a late stage is still to be revealed, but they clearly didn't see fit to hold back the report in order to incorporate Henderson's findings.

Meanwhile, the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media, together with their supporters on social media, have seized on this as evidence that the OPCW "has been hijacked at the top by France, UK and the US". The OPCW certainly has a lot of explaining to do, but the reality may turn out to be rather less dramatic than that.

UPDATE: On 16 May, in response to media enquiries the OPCW issued the following statement:

The OPCW establishes facts surrounding allegations of the use of toxic chemicals for hostile purposes in the Syrian Arab Republic through the Fact-Finding Mission (FFM), which was set up in 2014.

The OPCW Technical Secretariat reaffirms that the FFM complies with established methodologies and practices to ensure the integrity of its findings. The FFM takes into account all available, relevant, and reliable information and analysis within the scope of its mandate to determine its findings.

Per standard practice, the FFM draws expertise from different divisions across the Technical Secretariat as needed. All information was taken into account, deliberated, and weighed when formulating the final report regarding the incident in Douma, Syrian Arab Republic, on 7 April 2018. On 1 March 2019, the OPCW issued its final report on this incident, signed by the Director-General.

Per OPCW rules and regulations, and in order to ensure the privacy, safety, and security of personnel, the OPCW does not provide information about individual staff members of the Technical Secretariat

Pursuant to its established policies and practices, the OPCW Technical Secretariat is conducting an internal investigation about the unauthorised release of the document in question.

At this time, there is no further public information on this matter and the OPCW is unable to accommodate requests for interviews.

OPCW and the leaked Douma document: what we know so far

Blog post, 21 May 2019: Claims that international investigators "suppressed" evidence relating to chemical weapons in Syria have been circulating on social media during the past week. The renewed controversy revolves around two conflicting documents, both emanating from the Organisation for Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

The first one is the official report from the OPCW's Fact-Finding Mission (FFM), published in March, which found "reasonable grounds" for believing a toxic chemical had been used as a weapon in Douma last year. It suggested the chemical involved was chlorine gas, delivered by cylinders dropped from the air – implying that the Assad regime was responsible, since rebel fighters in Syria had no aircraft.

The second document is a 15-page internal memo which surfaced on the internet last week after someone leaked it. Written by an employee of the OPCW named Ian Henderson, it contradicts the FFM's findings. In particular, it disputes that the cylinders were dropped from the air and says it's more likely they were "manually placed" in the spot where they were found.

If true, that would support long-standing claims by Russia and the Syrian government that there was no chemical attack in Douma and that rebels planted the cylinders in order to falsely accuse the regime.

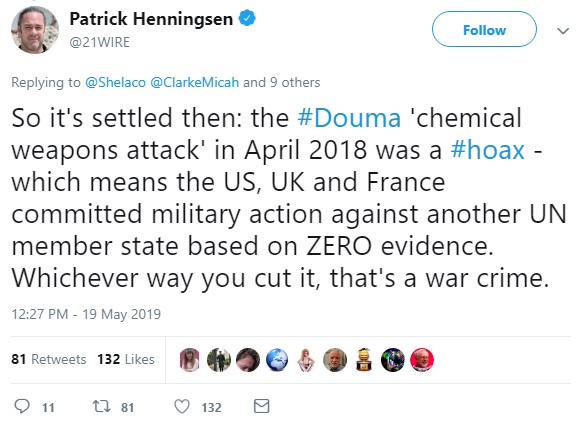

Almost immediately after the leaked document appeared, Assad supporters and various conspiracy theorists began claiming that it disproved the FFM's findings and exonerated the regime. Here's one example:

The Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media (which not only defends the Assad regime against accusations of using chemical weapons but also disputes Russia's use of a nerve agent against the Skripals in Britain last year) went further. Noting that Henderson's conclusions were not mentioned in the FFM's report, it claimed there had been a plot to suppress the truth. The OPCW, it said, "has been hijacked at the top by France, UK and the US".

Obviously, the leaked document and the FFM's report can't both be right. While Henderson's document certainly challenges the FFM's findings, claiming that it disproves them is – on current information – a step too far. Similarly, while it's clear that the FFM rejected Henderson's conclusions, the idea that this was done for political reasons is not supported by credible evidence. There could be far less sinister explanations – such as flaws in his analysis.

The problem here is that nobody outside the OPCW knows what internal discussions took place regarding the Douma investigation, and the OPCW isn't saying. That's the way it operates. It investigates quietly and discreetly, and when it eventually publishes its findings it expects the public to trust its expertise. The rationale for working in this way is that it prevents outsiders from interfering but in the internet age it also creates an opening for conspiracy theories about what might be happening behind closed doors.

A question of interpretation

While the fundamental question – about why Henderson's conclusions were rejected – remains unanswered, there are clues about the process by which he arrived at them.

Contrary to the impression given by some Twitter users, Henderson and the FFM were both relying on the same basic evidence. The evidence was compiled by the FFM which carried out on-the-spot investigations in Syria. Henderson's document is labelled as an "engineering assessment" and says its assessment was "conducted using sources of information available to the FFM team".

The dispute, therefore, is about how to interpret the evidence rather than the evidence itself.

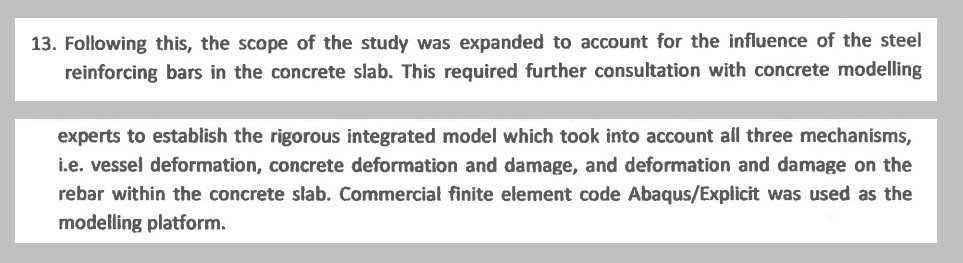

In the case of the cylinders, the FFM's investigation was a highly technical business. It involved complex analysis, including computer modelling, to try to establish whether they were dropped from the air. Details of this analytical process are covered by the OPCW's rules of confidentiality but the FFM's report does give some indications of how its investigators went about the task.

It says the FFM requested three independent analyses from internationally-recognised experts. The experts came from three different countries and had expertise in engineering, ballistics, metallurgy, construction, and other relevant fields. The experts used "different methodologies and approaches for their analyses in order to produce more comprehensive results".

Henderson's "engineering assessment" also made use of experts. It's unclear how many, or who they were, but they seem to have been different experts from those consulted by the FFM. According to the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media, "two European universities" were involved.

A timeline in the FFM's report shows it was consulting with the chosen experts during October and November last year, and received their findings in December.

There's no information about when Henderson's experts were consulted but the leaked document is dated 27 February this year – just two days before the FFM's report was published and two clear months after the FFM's experts had submitted their findings.

One question this raises is whether Henderson's assessment arrived too late to be considered by the FFM in its report, but a statement issued by the OPCW last week in response to journalists' enquiries appeared to discount that. It said: "All information was taken into account, deliberated, and weighed when formulating the final report regarding the incident in Douma ..."

We also know from the leaked version of Henderson's assessment that it was not the first draft – so when he handed it in on 27 February it's unlikely to have come totally out of the blue.

There's little doubt that Henderson was acting with the knowledge of others in the OPCW. His document is marked "for internal review" and, in the light of the OPCW's confidentiality rules, the fact that he consulted outsiders probably means he had received clearance from above.

A dissenting voice

Henderson's motives for producing his own assessment on Douma are less clear, though it does seem that he was a dissenting voice within the OPCW.

Firstly, the date on the leaked document suggests he knew, at least in broad terms, of the conclusions reached by the FFM's experts, was sceptical about them, and set out to counter them.

Secondly, there are signs that Henderson was critical of the FFM's methodology. The FFM had been trying to establish whether or not the cylinders found in Douma had been dropped from the air. In the leaked document he implies that this was the wrong approach and insists that alternative explanations – such as rebels planting the cylinders – ought to be explored.

When assessing the evidence, he says, it's necessary to develop hypotheses for what might have happened, but this should be done in a way that doesn't "pre-judge the situation or lead prematurely to a mistaken interpretation of the facts". He adds that in preparing his own assessment "an attempt was made to define a set of assumptions and at least two clear opposing hypotheses ..."

Although it's not spelled out explicitly, he appears to be claiming that his own methodology was superior to that of the FFM.

An unlikely whistleblower

If we accept that Henderson was a dissenter within the OPCW, the next question is whether he was a whistleblower too. Was he the person who leaked the document?

On 10 May, David Miller, a professor at Bristol University who is a prominent member of the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media, posted this tweet:

It's likely that the sender of the anonymous letter was the person who leaked the document, because on the following day the Working Group contacted the OPCW enquiring about Henderson (and was told he had never been a member of the FFM). A couple of days after that, the Working Group posted the leaked document on its website, along with a commentary.

There are several reasons for thinking Henderson was not the leaker.

It's worth noting that the leaked document surfaced 11 weeks after the FFM's report was published – which suggests that someone had only recently found out about it. If Henderson had decided to leak it himself, it would have made more sense to do so much earlier, while the FFM's report was still topical.

Misinformation in the Working Group's commentary also suggests they had no direct contact with Henderson but had been talking to someone else who had scanty knowledge of his work at the OPCW.

The commentary asserted that Henderson was a member of the FFM (despite the OPCW's denial) and had gone to Syria as part of that work. It also asserted that an "engineering sub-group" which helped with Henderson's assessment had been in Douma as part of the FFM.

There's no evidence that any of that is true and the Working Group has not responded to repeated requests via Twitter for an explanation.

Meanwhile, a handwritten note on the Henderson document suggests that the copy supplied by the leaker had been obtained from one of the document's recipients rather than the author.

The note says "Final version – for comments (by hand to TM only)" and gives rise to a further puzzle. Who or what is TM?

The Working Group's commentary says: "We understand that 'TM' in the handwritten annotation denotes Team Members of the FFM."

A search of the OPCW's website shows "TM" is used in several official documents, but not as an abbreviation for "Team Members". It's short for "Talent Management" – the name adopted by the OPCW for its human resources department.

Since it's unlikely that the human resources department would be interested in Henderson's views on Douma, the most probable explanation is that "TM" represents someone's initials.

- You can view the research for this story via Write in Stone.