Syria and the 'Zio-American plot'

Blog post, 8 January 2012: Denying the authenticity of the Syrian uprising is a central plank of the Assad regime's propaganda message – that the whole thing, as the official news agency put it recently, is a "Zio-American" plot.

To anyone who has been following events in Syria closely since last March, the regime's conspiracy claims are not only ridiculous but terribly insulting to the thousands of protesters who have risked (and often lost) their lives in the struggle against dictatorship. Even so, there's a small chorus of westerners who seem to be echoing the Assad line.

"Arguably, the most important component in this struggle," Aisling Byrne wrote in an article last week, "has been the deliberate construction of a largely false narrative that pits unarmed democracy demonstrators being killed in their hundreds and thousands as they protest peacefully against an oppressive, violent regime, a 'killing machine' led by the 'monster' Assad."

Arguably, my foot. Information about the protests has sometimes been wrong – as always happens in conflicts, especially when media access is so severely restricted – but to suggest that this has led to a "largely false narrative" is utter nonsense.

Byrne's article has been doing the rounds on the internet – Counterpunch, the Asia Times and Countercurrents – as well as being touted enthusiastically inside Syria by the Assad regime. Running to more than 4,700 words, it's probably the fullest exposition yet of the grand international conspiracy theory.

Of course, it's true lots of countries have been reacting to the uprising in Syria and some are certainly trying to influence the outcome. Given Syria's strategic importance, that is to be expected. Reacting to events, though, is not the same as orchestrating things according to some pre-conceived plan – which is what the Assad regime claims is happening, and what Byrne also seems to imply:

"What we are seeing in Syria is a deliberate and calculated campaign to bring down the Assad government so as to replace it with a regime 'more compatible' with US interests in the region.

"The blueprint for this project is essentially a report produced by the neo-conservative Brookings Institute for regime change in Iran in 2009."

There's no harm in discussing or criticising what foreign powers may be up to with regard to Syria, even if Byrne draws some rather fanciful conclusions. Any attempts to prevent the Syrian people from making their own choices ought to be resisted, too. The overall effect of such articles, though, is to delegitimise the popular struggle – which is unfair to the protesters and also plays into the hands of the regime.

But what of the article's author, Aisling Byrne? She is projects co-ordinator for the Conflicts Forum, based in Beirut. Its director is Alastair Crooke, a former British intelligence officer who until a few years ago was heavily involved in British and European diplomacy relating to Israel/Palestine. Among many other things, he took part in clandestine meetings with Hamas.

Crooke left his government job and founded the Conflicts Forum in 2004 "to open a new relationship between the west and the Muslim world", mainly through promoting dialogue with Islamist movements – something that western governments have often been reluctant to do. Members of the forum's advisory board include Moazzam Begg, a former Guantanamo detainee, and Azzam Tamimi, regarded as an unofficial voice for Hamas in Britain.

"While facing increasingly intractable problems in Iraq, Afghanistan, Lebanon, Pakistan and elsewhere," Conflicts Forum says on its website, "we [ie western governments] immobilise ourselves by turning away from the homegrown political forces that have the power to resolve these crises."

Judging by Byrne's article and another by Crooke himself in the Guardian last November, though, Conflicts Forum seems oddly reluctant to engage with the "homegrown political forces" in Syria.

There's an inconsistency and selectivity here that is also apparent among sections of the more traditionalist left. Pro-western dictators like Ben Ali and Mubarak are considered fair game, but when it comes to toppling contrarian dictators like Gaddafi and Assad there's lingering sympathy for them.

In Syria's case this is further complicated by viewing the uprising through the prism of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. For instance, a briefing paper on Conflicts Forum's website examining Hizbullah's continuing support for the Assad regime says:

"Just as Hizbullah viewed the 2009 protests in Iran as a 'bid to destabilise the country's Islamic regime' by means of a US-orchestrated 'velvet revolution', the protests in Syria are branded a form of 'collusion' with outside powers who seek to replace Asad's rule with 'another regime similar to the moderate Arab regimes that are ready to sign any capitulation agreement with Israel'...

"Echoing Hizbullah's stance on the Iran protests is Nasrallah's characterisation of the US role in the Syrian uprising as an extension of the July War and the Gaza War. Since the resistance in Lebanon and Palestine had foiled the 'New Middle East' scheme in both these military aggressions, Washington was 'trying to reintroduce [it] through other gates,' such as Syria.

"With this in mind, attempts to overthrow the Assad regime are considered a 'service' to American and Israeli interests."

Such views are not confined to Hizbullah, however. But how realistic are they? Many neocons hoped the invasion of Iraq would deliver a pro-Israel government there. It didn't, and instead it strengthened Iran.

Tunisia is no more favourably disposed towards Israel than it was under Ben Ali. Nor is Libya. Nor is Egypt – if anything, less so. And a democratic Syria would still have the same territorial issues with Israel – the occupied Golan Heights, etc – that it has now. In any case Israel seems an odd reason for denying Syrians a chance to determine their own future.

Former British ambassador in Syria has links to Assad family

Blog post, 23 April 2017: Since leaving the diplomatic service Peter Ford, a former British ambassador in Damascus, has become an outspoken critic of western policies towards Syria and has described calls for President Assad to step down as "child-like".

During the conflict Ford has also repeatedly disputed evidence of atrocities by the Assad regime. Last September, when a UN humanitarian convoy was attacked in Aleppo killing 14 civilian aid workers and injuring at least 15 others, he suggested rebel fighters were responsible – even though the attack came from the air, and only Syrian and Russian air forces were operating in the area. A report by UN investigators later described the attack as "particularly egregious" and said:

"The types of munitions used, the breadth of the area targeted and the duration of the attack strongly suggest that the attack was meticulously planned and ruthlessly carried out by the Syrian air force to purposefully hinder the delivery of humanitarian aid and target aid workers, constituting the war crimes of deliberately attacking humanitarian relief personnel, denial of humanitarian aid and targeting civilians."

In February, Ford appeared in a radio programme produced by the Russian government's Sputnik News disputing a report by Amnesty International about atrocities in Saydnaya prison near Damascus. Amnesty had accused the Assad regime of carrying out mass extrajudicial killings at the prison "as part of an attack against the civilian population that has been widespread, as well as systematic, and carried out in furtherance of state policy".

Earlier this month, after bombing by the Syrian air force in Khan Sheikhoun led to dozens of people being killed by Sarin (or a similar banned substance) and hundreds more injured, Ford was again eager to exonerate the regime. Interviewed on BBC television, he told viewers it "is simply not plausible" and "it defies belief" that Assad would have used Sarin, and "he probably didn't do it".

On the same day, Ford could be seen on RT, the Russian propaganda channel, describing reports of the attack as "incredible". "It beggars belief," he said. "They [the Assad regime] had absolutely zero motive for doing it and a hundred reasons not to do it." (He has previously also spoken sympathetically about the regime on the Iranian channel Press TV.)

Meanwhile, in an unchallenging interview by former Guardian journalist Jonathan Steele, Ford told the Middle East Eye website it would be "out of character" for Assad to provoke the US by launching a chemical attack.

Promoting the interview on Twitter, Steele described Ford as "one of the bravest former ambassadors Britain has". Several other Twitter users praised Ford for his "very clear, level-headed assessment of recent events", for refuting "BBC propaganda" and dropping "truth bombs". Among others delighted by Ford's BBC interview was The Canary website which has previously hailed the Assad regime's "openness and tolerance", and which asserted "there is no evidence that Assad carried out the attack".

Ford's credentials as a former ambassador have misled some people into thinking his views on Syria are worth listening to. But what none of his many interviewers has so far mentioned (or perhaps even been aware of) is his connection with the Assad family.

Since February, Ford has been a director of the British Syrian Society which is headed by Assad's father-in-law, Fawaz Akhras.

The society, which is registered in Britain as a limited company, was founded in 2002 during a period when Assad, recently installed in power, seemed interested in reform. Numerous high-profile British figures with a background in foreign policy were happy to join it at the time.

Since the conflict broke out in Syria, however, the society has been mired in controversy – especially over Akhras's leadership. In 2012 it emerged that Akhras, a British-Syrian cardiologist and the father of Assad's wife, Asma, had been emailing advice to the president about how to rebut allegations of torture.

Records at Companies House show that no fewer than 28 people appointed at various times as directors of the society later resigned. It currently has seven directors, including Akhras and Ford. The only other British-based director is Syrian-born Ghayth Armanazi who was formerly head of the Arab League's mission in London. The remaining four directors – Ayman al-Chilabi, Costi Chehlaoui, Karim Khwanda and Omar Fouad Takla – are shown in the records as residents of Syria.

The society's published financial records are sketchy but the most recent accounts (2015) show assets of £131,000. There are no details of income and expenditure but earlier accounts show that between 2008 and 2011 it was spending on average £194,000 a year.

The Syrian conflict's anti-propaganda propagandists

Blog post, 24 February 2018: In times of war it's important but often difficult to distinguish truth from propaganda. So the newly-formed "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" – comprising three professors, two lecturers and three postgraduate researchers at British universities – ought to be a welcome development.

"At present," the group say, "there exists an urgent need for rigorous academic analysis of media reporting of this war, the role that propaganda has played in terms of shaping perceptions of the conflict and how these relate to broader geo-strategic process within the [Middle East] region and beyond."

The group's aim, they continue, is to "encourage networking amongst academics as well as the development of conference papers and panels, articles and research monographs, and the development of research funding bids. We also aim to provide a source of reliable, informed and timely analysis for journalists, publics and policymakers."

So far, so good. But on closer examination the working group itself seems more like a propaganda exercise than a serious academic project.

Published articles by leading members of the group give plenty of clues as to what the project is really about. They dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation. They are critical of western governments, western media and various humanitarian groups but show little interest in applying critical judgment to Russia's role in the conflict or to the controversial writings of several journalists who happen to share their views.

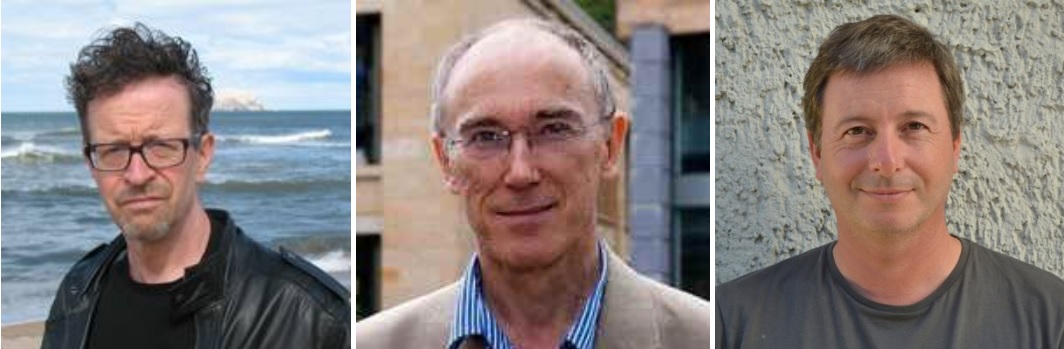

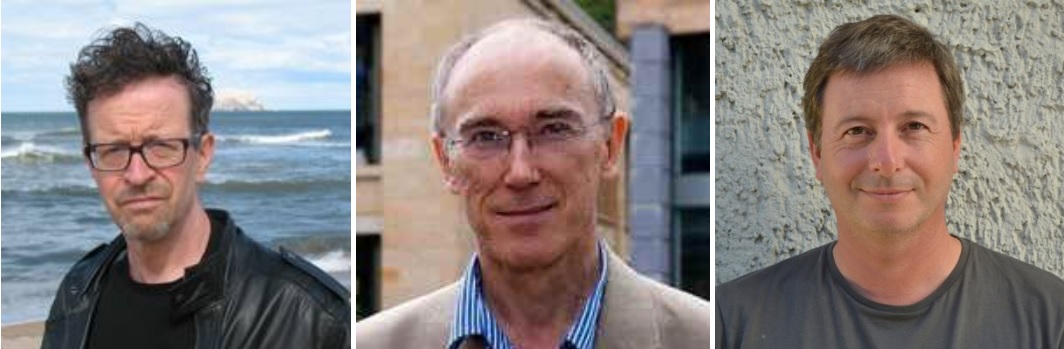

The group's steering committee consists of Tim Hayward, Professor of Environmental Political Theory at Edinburgh universiy, Paul McKeigue, Professor of Genetic Epidemiology and Statistical Genetics (also at Edinburgh) and Professor Piers Robinson, Chair in Politics, Society and Political Journalism at Sheffield university.

On the Edinburgh university website Prof Hayward's iconoclastic postings about "how we were misled" over Syria" include critiques of Amnesty International, Médecins Sans Frontières and the British Channel 4 News. There's plenty more, in a similar vein, on his personal website.

Probability theory

Meanwhile, two articles on the question of chemical weapons in Syria by Prof McKeigue (here and here) adopt a highly original approach – original to the point of absurdity. Using "probability calculus", with some assistance from Bayes’ theorem and Hempel’s paradox, McKeigue evaluates various hypotheses regarding the events in Ghouta (2013) and Khan Sheikhoun (2017).

He concludes there is "overwhelming" evidence that these were not chemical attacks by the Assad regime but "a managed massacre of captives [by rebels], with rockets and sarin used to create a trail of forensic evidence that would implicate the Syrian government in a chemical attack".

This, he adds, "has quite radical implications for the credibility of western media, western governments and international agencies such as OPCW [Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons]; you may reasonably ask 'how could they have got it so wrong?'."

At Sheffield university, Prof Robinson is also a chemical weapons sceptic (though in a more conventional way) and a critic of the White Helmets. He views the Syrian conflict as part of a western strategy of regime change dating back to the 2003 Iraq war:

"The bottom line here is that, given their desire for regime change in Syria, and for precisely the same reasons that intelligence was spun in the Iraq case, there are powerful incentives for western governments to distort and exaggerate in the case of Syria in order to create the casus belli they so desperately want ...

"With respect to Syria, it is now well established that there have been significant propaganda activities designed to manipulate public opinion in support of western regime change objectives."

Other members of the group, according to its website, are Dr Florian Zollmann, a lecturer in journalism at Newcastle university, Dr Tara McCormack, a lecturer in politics and international relations at Leicester university who also has a regular slot on Russia's Sputnik News, and three PhD candidates: Louis Allday (SOAS, University of London), Divya Jha and Jake Mason (both at Sheffield university).

Mason is working on a thesis entitled "Spinning Syria: The development and function of the British government's propaganda in the Syrian Civil War", supervised by Prof Robinson. The group's website was registered in Mason's name on January 25 this year.

'Rigorous academic analysis'

The "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" is essentially a campaigning organisation. Its members, of course, have a right to express their opinions and promote them through activism. The worrying part, though, especially in the light of their stated intention to seek "research funding", is their claim to be engaging in "rigorous academic analysis" of media reporting on Syria.

If that's the aim, the same level of academic rigour needs to be applied across the board, But while members of the group are generally very critical of mainstream media in the west, a handful of western journalists – all of them controversial figures – escape similar scrutiny. Instead, their work is lauded and recommended.

One of the journalists is Max Blumenthal whose views on the white helmets (here and here) are shared by the working group. The two favourites, though, are Eva Bartlett and Vanessa Beeley – "independent" journalists who are frequent contributors to the Russian propaganda channel, RT. Bartlett and Beeley also have an enthusiastic following on "alternative" and conspiracy theory websites though elsewhere they are widely dismissed as propagandists. Either way, their activities are part of the overall media battle regarding Syria and any "rigorous academic analysis" of the coverage should be scrutinising their work rather than promoting it unquestioningly.

Russia's role

The working group also claims to be researching "the role that propaganda has played in terms of shaping perceptions of the conflict and how these relate to [the] broader geo-strategic process". It's difficult to see how that can be done without taking into account Russia's propaganda strategy and its efforts to influence opinion in the west.

Prof Robinson has a rather charitable view of Russia's English-language media, such as RT and Sputnik News. He doesn't deny they are propaganda channels but objects to the idea that western media are somehow different. Writing in the Guardian, he says:

"Whatever the accuracy, or lack thereof, of RT and whatever its actual impact on western audiences, one of the problems with these kinds of arguments is that they fall straight into the trap of presenting media that are aligned with official adversaries as inherently propagandistic and deceitful, while the output of 'our' media is presumed to be objective and truthful. Moreover, the impression given is that our governments engage in truthful 'public relations', 'strategic communication' and 'public diplomacy' while the Russians lie through 'propaganda'."

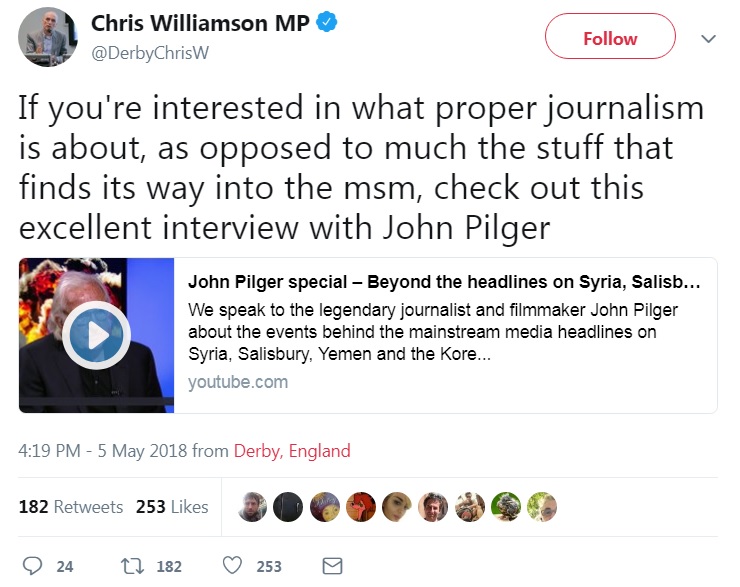

He goes on to say: "One can gain useful insights and information from a variety of news sources – including those that are derided as 'propaganda' outlets: Russia Today, al-Jazeera and Press TV should certainly not be off-limits." Separately, when various British politicians were criticised for appearing on RT, Robinson rose to their defence:

"People are coming on RT in order to express legitimate political views and they are coming onto RT because they are probably having great difficulty getting onto existing ‘legitimate’ mainstream media in the west. In many ways RT is providing an important outlet for these people who are not getting their voices heard elsewhere."

But Putin clearly doesn't fund RT in order to support free speech, and suggesting the key difference between western propaganda and Russian propaganda is in the way they are perceived misses an important point. The Russians have been developing new propaganda techniques for the internet age and applying them to the Syrian conflict – which is one reason why they are worth studying.

RT's slogan is "Question More" – and it's brilliantly mischievous, because questioning more sounds like something we all should be doing. Scepticism is healthy, but only up to a point. Obviously, people should be encouraged to view media – in the west as elsewhere – with a critical eye and look out for attempts to manipulate them. Problems start, though, when people become so sceptical that they can't recognise truth when it's presented to them.

This is where RT's mischief-making comes in. Questioning more – Moscow style – is about manufacturing uncertainty.

Examples of the technique can be seen in Russia's response to the shooting down of flight MH17 over Ukraine and the chemical attacks in Syria. The trick is to cast doubt on rational but unwelcome explanations by advancing multiple alternative "theories" – ideas that may be based on nothing more than speculation or green-ink articles on obscure websites.

It doesn't much matter if some of the theories are mutually contradictory or highly fanciful, because the purpose is not to persuade people that any particular theory is correct, The point is to cause so much confusion that people have no idea what to believe.

This might seem like an obvious issue for the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media to be looking at. But don't hold your breath. Prof Robinson has already been complaining onTwitter about "the crazed obsession with Russia".

Manufacturing doubt over chemical weapons in Syria

Blog post, 27 February 2018: At a recent meeting of the UN security council Syria claimed the US and France now doubt that the Assad regime has ever used chemical weapons. The claim was false but it provides an interesting example of how propaganda can be created.

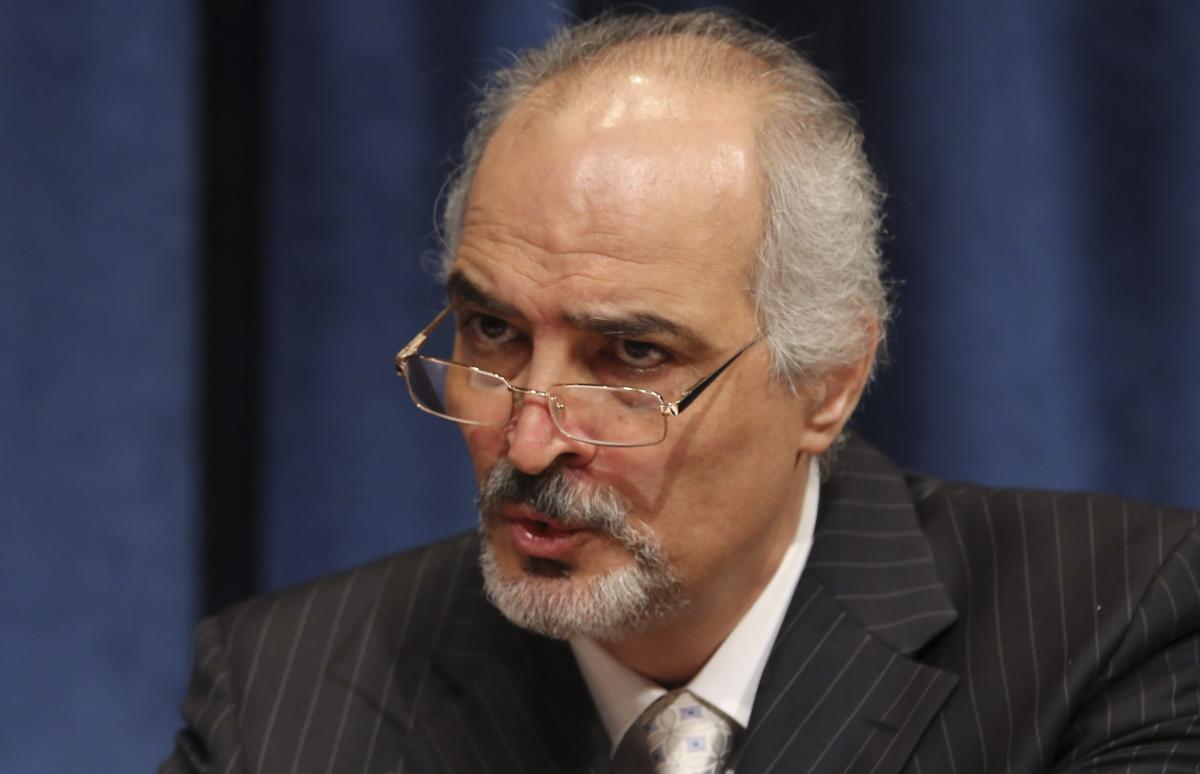

Speaking on February 14, Syria's representative at the UN, Bashar Ja'afari, told the council:

"One of the most important political magazines, the American Newsweek, published an article on 8 February written by Ian Wilkie entitled 'Now Mattis Admits There Was No Evidence Assad Used Poison Gas on His People'.

"The United States Secretary of Defence admits in that article that there is no proof of the use of toxic gas by the Syrian government against its people, neither in Khan Shaykhun [last year] nor in Al-Ghouta in 2013."

Mattis had said no such thing. In fact, he said the Assad regime was to blame for both attacks.

Laboratory tests by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) have previously established that the sarin involved was of a type manufactured by the regime.

Ja'afari's claim arose out of a news conference at the Pentagon on 2 February where Mattis was questioned about reports of recent chemical attacks in Syria using chlorine.

"Is this something you're seeing that's been weaponised?" a reporter asked.

"It has," Mattis replied, adding that the deadly nerve agent sarin may have been used too: "We are more – even more concerned about the possibility of sarin use, the likelihood of sarin use, and we're looking for the evidence."

Mattis explained that there were "reports from the battlefield" from people who claimed sarin had been used. but added: "We do not have evidence of it. But we're not refuting them; we're looking for evidence of it."

He said the American suspicions of renewed sarin use arose partly out of the Assad regime's previous behaviour: "they were caught using it" during the Obama administration (a reference to the Ghouta attacks in 2013) and "they used it again" after Trump became president (Khan Sheikhoun in 2017).

Mattis's phrase, "We do not have evidence", was clearly referring to the allegations of new chemical attacks but the Russian propaganda channel, RT, latched on to it and re-purposed it in a report which began:

"Washington has no evidence that the chemical agent sarin has ever been used by the Syrian government, Pentagon chief James Mattis has admitted" (italics added).

A few days later Newsweek magazine published a similar claim, with an article headed: "Now Mattis admits there was no evidence Assad used poison gas on his people".

The article's author, Ian Wilkie, described Mattis's "no evidence" statement as "striking" and continued:

"Mattis offered no temporal qualifications, which means that both the 2017 event in Khan Sheikhoun and the 2013 tragedy in Ghouta are unsolved cases in the eyes of the Defense Department and Defense Intelligence Agency."

This was completely untrue, as Wilkie would have seen if he had bothered to check the transcript of the news conference. Despite numerous people pointing out Wilkie's error, Newsweek did not withdraw the article or add a correction. Instead, 10 days later, it published a second article from Wilkie claiming "the Assad regime’s culpability is vastly under-proven by the public evidence". Newsweek described Wilkie as "an international lawyer and terrorism expert and a veteran of the US Army (Infantry)".

'Corroboration' from France

In his speech to the UN, Ja'afari then went on to claim Mattis's misreported words had been corroborated by France:

"The French Minister of Defence, Florence Parly, also said yesterday, like her American counterpart, that there is no documented proof of the use of chlorine gas by the Syrian Government."

A closer look, though, shows that Parly's words had also been twisted.

Last May, shortly after becoming president of France, Emmanuel Macron said he viewed chemical weapons as a red line: "Any use of chemical weapons would result in reprisals and an immediate riposte, at least where France is concerned."

In a radio interview on 9 February, armed forces minister Parly was asked, in the light of fresh reports about chemical attacks, if Macron's red line had now been crossed. (The original transcript in French is

here.)

Interviewer: Do you have confirmation, I mean confirmation, that barrels of chlorine have been used by Syrian regime forces against Syrian civilians?

Minister: We have possible indications of chlorine use, but we do not have absolute confirmation, so it is this confirmation work that we are doing, with others elsewhere, because obviously the facts must be established.

Interviewer: Last May Emmanuel Macron indicated that a very clear red line – I'm quoting – existed on our side, on the side of France, and therefore use of a chemical weapon by anyone – I'm still quoting the president – would be the object of reprisals and an immediate response from the French. We are there, aren't we?

Minister: Exactly, we can't say it with certainty, and that is what we must achieve.

Interviewer: So, for the moment, for lack of proof, the red line has not been crossed?

Minister: For the moment, for lack of certainty about what has happened, about the consequences of what has happened, we cannot say that we are there ...

Use of chlorine as a chemical weapon is more difficult to confirm than sarin through laboratory tests, which may partly explain the French minister's hesitancy.

In 2014, however, a fact-finding mission from the OPCW concluded "with a high degree of confidence" that chlorine had been used:

"Thirty-seven testimonies of primary witnesses, representing not only the treating medical professionals but a cross-section of society, as well as documentation including medical reports and other relevant information corroborating the circumstances, incidents, responses, and actions, provide a consistent and credible narrative.

"This constitutes a compelling confirmation that a toxic chemical was used as a weapon, systematically and repeatedly, in the villages of Talmanes, Al Tamanah, and Kafr Zeta in northern Syria. The descriptions, physical properties, behaviour of the gas, and signs and symptoms resulting from exposure, as well as the response of the patients to the treatment, leads the FFM [Fact-Finding Mission] to conclude, with a high degree of confidence, that chlorine, either pure or in mixture, is the toxic chemical in question."

A further report provided more detail.

Russia-friendly 'Syria propaganda' group names more supporters

Blog post, 6 March 2018: The newly-formed "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" – which I wrote about last month – has added some further names to its list of members and advisers.

The group claims to be promoting "rigorous academic analysis" of propaganda in the Syrian conflict and says it aims to "provide a source of reliable, informed and timely analysis for journalists, publics and policymakers".

The 14 members and advisers named on the group's website are academics – mostly at British universities – and the group says it intends to bid for research funding.

However, published articles by members of the group cast doubt on their claims of "rigorous academic analysis". They dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation.

They are critical of western governments, western media and various humanitarian groups but show little interest in applying critical judgment to Russia's role in the conflict. One of their members, Dr Tara McCormack of Leicester university, has a regular slot on Russia's Sputnik News.

Members of the group uncritically cite work by Eva Bartlett and Vanessa Beeley – two "independent" journalists who have an enthusiastic following on "alternative" and conspiracy theory websites but are widely regarded elsewhere as propagandists.

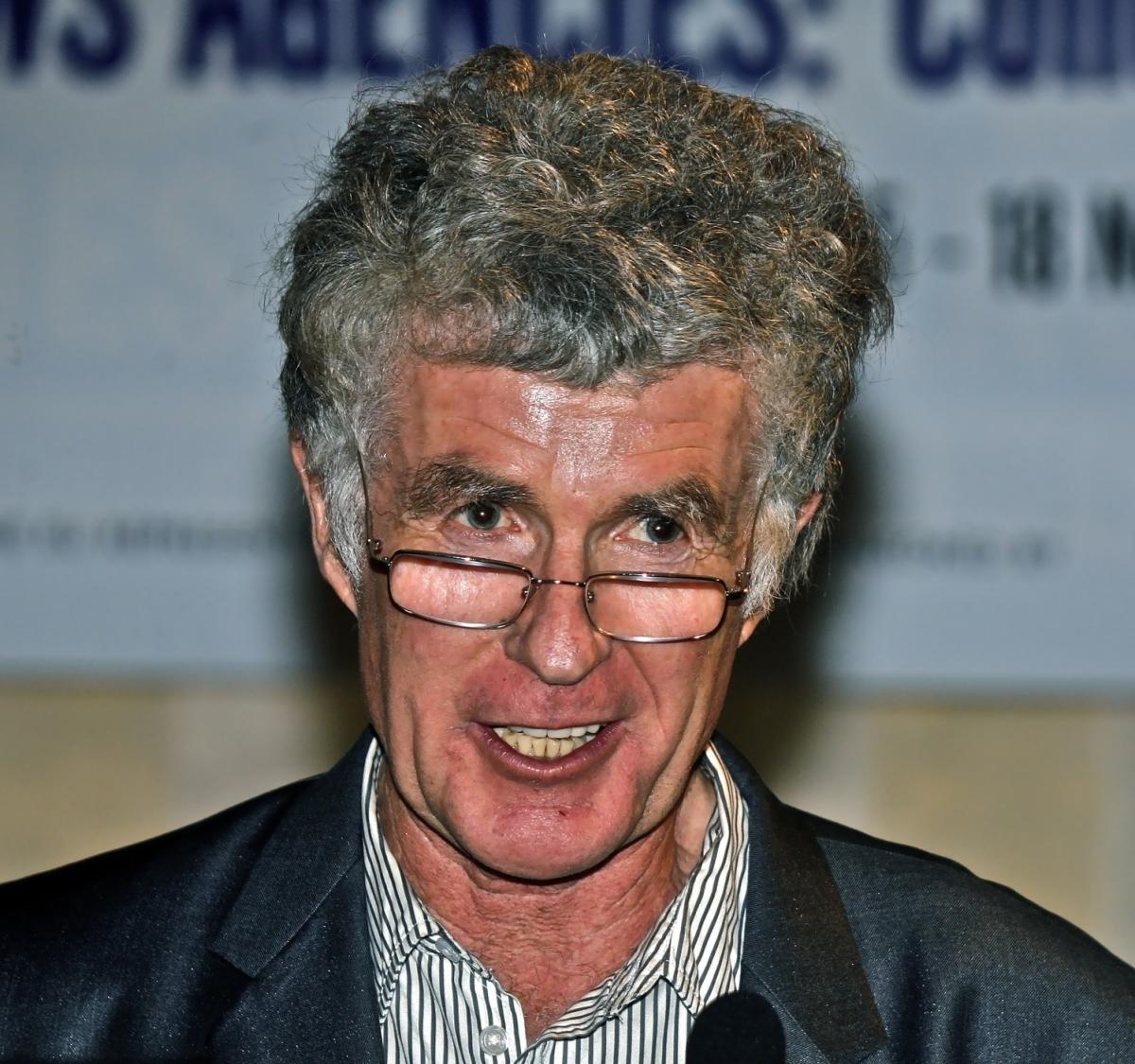

The group's most recent new member is Irish-born Oliver Boyd-Barrett, an emeritus professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio.

Boyd-Barrett has written or contributed to numerous books about the media, including one on "media imperialism" and one on the globalisation of news.

Another of his books, Western Mainstream Media and the Ukraine Crisis: A Study in Conflict Propaganda has a chapter about the shooting-down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2014.

Boyd-Barrett devotes much of the chapter to casting doubt on reports about the crash in western media. He concludes that the "preponderance of evidence" seems to "support the contention that MH17 was brought down by a missile fired from a Russian-made BUK" but says "full consensus as to the facts may never be achieved".

He goes on to say the MH17 crash (which killed 298 people) "has been deployed as a red herring to distract attention from the main issues concerning the Ukraine crisis ... and, instead, beating up a lather of western public repugnance for Russia in general, Vladimir Putin in particular, and the ethnic Russian separatists of Eastern Ukraine."

In addition, he accuses the Ukrainian authorities of "criminal negligence" for failing to close their airspace to civilian flights.

The chapter also talks about "comparable false confidence alleging Assad's use of chemical weapons in Syria", saying such claims have been "refuted" by Richard Lloyd and Ted Postol of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media says it is in the process of setting up an "International Advisory Board" and lists five names on its website.

One of these is Iraqi-born Sami Ramadani, described as an "independent researcher". Ramadani is better known as a prominent member of the Stop the War Coalition (STWC) where he serves on the steering committee.

Ramadani has also made numerous appearances on the Russian propaganda channel, RT.

STWC has been embroiled in controversy during the Syrian conflict because of its reluctance to criticise actions by Russia and the Assad regime.

Its "Anti-War Charter" calls for "an end to foreign policy based on Washington’s global ambitions or on a junior imperial role for Britain" but it also calls for "an immediate initiative to de-escalate tension with Russia".

In 2013, STWC invited Mother Agnes, a Syrian-based nun who was sympathetic towards the regime, to speak at one of its conferences. Mother Agnes, who was sympathetic towards the Assad regime, had produced a report disputing the authenticity of videos showing victims of sarin attacks.

Three of the videos, she said, showed "artificial scenic treatment using the corpses of dead children", while in others she suggested the children were anaesthetised or merely sleeping. Human Rights Watch dismissed Mother Agnes's claims as baseless but the Russian propaganda channel, RT, continued to treat her as a quotable source.

Two other speakers at the STWC conference refused to share a platform with her and she eventually withdrew.

Besides Ramadani, others named as members of the advisory board for the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media are Dr Christopher Davidson (University of Durham, UK), Professor Richard Jackson (University of Otago, New Zealand), Professor Richard Keeble (University of Lincoln, UK) and Professor Roger Mac Ginty (University of Manchester, UK).

UPDATE, 7 March 2018: Today, the working group added three more names to its website. Dr Greg Simons (Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University) is an additional member. Professor Philip Hammond (London South Bank University) and Professor Mark Crispin Miller (New York University) have been added to the "International Advisory Board". Sami Ramadani's description has been changed to "retired Academic".

UPDATE, 8 March 2018: Today the name of Professor Roger Mac Ginty was removed from the group's website.

From Syria to Salisbury: Russia's propaganda game

Blog post, 15 March 2018: There's something uncannily familiar about Russia's propaganda antics over the poisoning of double agent Sergei Skripal in Britain. We've seen them before in Syria where Russia has steadfastly defended the Assad regime against accusations of using chemical weapons.

On an August morning in 2013 news began to emerge of mass deaths in Ghouta on the outskirts of Damascus. A report from Reuters began: "Syria’s opposition accused government forces of gassing hundreds of people on Wednesday by firing rockets that released deadly fumes over rebel-held Damascus suburbs, killing men, women and children as they slept."

Right from the start, there was little doubt about what had happened: videos of those affected showed classic symptoms of nerve agent poisoning. Within a month, UN inspectors confirmed the worst: the environmental, chemical and medical samples they had collected provided "clear and convincing evidence that surface-to-surface rockets containing the nerve agent sarin" had been used in Ghouta.

Sowing doubt

Given that these deaths and injuries occurred in rebel-held areas that were under attack from Syrian government forces and that the government had previously admitted possessing chemical weapons, there was one very obvious suspect. But Russia had other ideas.

Its first response was to question whether anything untoward had actually happened. On the day of the attack, an article posted on the Russia's RT website described the reports as "fishy" and claimed that international media had simply "picked up" the story from al-Arabiya, a Saudi TV channel which was "not a neutral in the Syrian conflict".

Meanwhile, Russia's foreign ministry spokesman, Aleksandr Lukashevich, hovered between denying an attack had taken place and claiming it had been staged (or perhaps faked) by anti-Assad forces. He talked about an "alleged" attack and a "so-called" attack while asserting that "materials of the incident and accusations against government troops" had been posted on the internet several hours in advance. "Thus, it was a pre-planned action," he said.

Lukashevich's argument had actually been cribbed from conspiracy theorists on the internet, but without checking properly. Reuters' report of the attack and some of the videos did appear to have been posted before the attack took place but that was simply the result of automated time-stamping in a different time zone.

Following publication of the UN inspectors' report, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov acknowledged that it showed chemical weapons had been used but said it offered no proof that Assad's forces were to blame. This implied the inspectors had failed to reach a conclusion about who was responsible but the terms of reference set by the UN had not allowed them to apportion blame.

Diversionary tactics

Lavrov went on to say that Russia still suspected rebel forces were behind the attack and that the UN report failed to answer a number of questions, including whether the weapons were produced in a factory or "home-made". He added that the UN report should be examined not in isolation but along with evidence from sources such as the internet and other media, including accounts from "nuns at a nearby convent" and a journalist who had spoken to rebels.

The questions Lavrov raised – about home-made sarin, the nuns in the convent and the journalist who had spoken to rebels – looked suspiciously like a diversionary tactic, and that is what they were. They didn't withstand serious scrutiny but in propaganda terms they didn't need to. The point was not to persuade people of anything in particular – which was one reason why many people had difficulty recognising it as propaganda.

The slogan of RT is "Question More", and its purpose is exactly that: to ask lots of questions, not in the hope of getting closer to the truth but in order to sow as much doubt as possible. This doesn't require real evidence and it doesn't matter if some of the "alternative" theories promoted are mutually contradictory or purely speculative, so long as there are plenty of them. If the result is that people become so confused they are unsure what to believe the propaganda can be considered a success.

Russia's propagandists also have a symbiotic relationship with conspiracy websites in the west which not only re-circulate and amplify the theories but sometimes generate them in the first place.

False flags in Salisbury?

Fast-forward to March 2018 and the English city of Salisbury where Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, were poisoned. As with Syria in 2013, there was one rather obvious suspect. The Skripals were Russian. Sergei had been a double agent in the murky world of espionage, and as far as Russia was concerned had betrayed his country.

Over the last 40 years a number of mysterious deaths in Britain have been linked to Russia or its predecessor, the Soviet Union. At least two of those involved murder by exotic means – Georgi Markov in 1978, stabbed with a ricin-tipped umbrella, and Alexander Litvinenko in 2006 who was killed with radioactive polonium. There have been other cases too, outside Britain.

Sergei and Yulia Skripal were found on a park bench "reportedly exhibiting symptoms similar to a drug overdose" according to Russia's RT. Another RT article suggested they might be drug users.

Amid the initial speculation about what might have caused the Skripals' poisoning, there was talk in several British newspapers that the substance involved might be fentanyl, a powerful opiate. One factor behind that idea was that fentanyl, or a version of it, is thought to have been used by Russian special forces to subdue Chechen separatists who held 800 people hostage at a Moscow theatre in 2002 (as the Sun newspaper pointed out). RT, however, had a different spin on the fentanyl angle:

"The highly addictive synthetic opiate has been linked to a sharp increase in overdoses in the US and has also resulted in dozens of deaths across the UK. The drug has repeatedly made headlines as part of the so-called ‘opioid crisis’, especially after famous American singer/songwriter Prince died from an accidental overdose of fentanyl in April 2016.

"An eyewitness told the BBC she saw a woman and a man sitting on a bench and that they 'looked like they’d been taking something quite strong'."

Since then, the Russians have moved on from trying to deny that a nerve agent attack took place, as they did in Syria over sarin. They are now promoting multiple "false flag" theories – as they also did in Syria over sarin. Daft as the theories might be, in Syria's case they found some vocal supporters in the west – and the same thing seems to be happening now with the Skripal affair.

"I think this will go down with the Gulf of Tonkin incident as one of the great hoaxes, with the most serious implications in all of history," former British MP George Galloway told Sputnik Radio's listeners.

With Syria, the main false flag theory was that rebels attacked themselves with sarin to create the pretext for a large-scale military intervention by western powers against the Assad regime. This was also linked to the dubious claim that western powers had spent years plotting "regime change" in Syria. Despite two confirmed sarin attacks, however, western powers have still not responded in the way the theory has been predicting.

With the Skripal affair, Russia is strongly suggesting a false flag operation carried out by the British government but is unclear about its exact purpose.

Galloway, who became notorious for his tribute to Saddam Hussein in 1994, suggested it might have something to do with Putin's re-election or the World Cup (which is due to be held in Russia this summer). The Russian foreign ministry also appears to favour a World Cup connection: the British are "unable to forgive" Russia for winning the right to host this summer's contest.

More vaguely, Sputnik quotes Helga Zepp-LaRouche – leader of the German Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität party and wife of the controversial American, Lyndon LaRouche – as blaming British intelligence for "fabricating another Litvinenko case as a pretext for another anti-Russia escalation". It's unclear why Sputnik regards her as an authority on the matter.

While mainly trying to direct suspicion towards Britain, the Russians are also speculating that some other country might be the culprit – almost any country apart from Russia. According to a former Kremlin adviser quoted by Sputnik News, "every laboratory in the west including Porton Down which is only seven miles away from Salisbury, has a sample" and there are "are rouge agents of a different nation that have gotten access to this particular nerve agent". The mention of "rouge" (rogue) agents may be intended as a reference to Ukraine.

These ideas have already acquired some resonance at the further ends of the political spectrum (both left and right) in the west. Look on Twitter and you will find that many of those adopting them have previously been active in questioning the Assad regime's sarin use.

Not surprisingly, there have been calls to cancel RT's television broadcasting licence in Britain – which would probably be a mistake. RT would have a field day complaining about being victimised, and blocking its TV output would have little practical effect. RT would still be able to function online, which in some ways may be more important because its propaganda is often circulated in the form of YouTube videos.

No matter what anyone does to try and stop it, though, propaganda will always exist. The important thing is to recognise it for what it is, and not to be fooled by it.

'Propaganda' professors switch focus from Syria to Britain and Russia

Blog post, 18 March 2018: A group of university professors who promoted conspiracy theories about chemical weapons in Syria are now making similar claims about the recent chemical attack in Britain which critically injured Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter.

The "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" was set up in January, comprising professors and other academics from universities in Britain, the US, Sweden and New Zealand.

It purports to be engaged in "rigorous academic analysis" of media reporting of the Syrian conflict and the role played by propaganda, but on closer examination the group itself seems more like a propaganda exercise than a serious academic project.

Previously published articles by members of the group cast doubt on their claims of "rigorous academic analysis". They dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation. Several of the group also make frequent appearances on the Russian propaganda channels, RT and Sputnik.

Last week the group published its first "working paper" and, rather oddly, it was not about Syria but about Britain and Russia.

The paper, co-authored by Professor Paul McKeigue of Edinburgh University and Professor Piers Robinson of Sheffield University, claims the British government has developed a way of producing the "novichok" compound that poisoned the Skripals.

Since the first confirmed use of a nerve agent in Syria in 2013, defenders of the Assad regime – and especially the Russian government – have been claiming it was a "false flag" attack by rebels, intended to discredit the regime.

Following the nerve agent attack in Britain earlier this month, similar "false flag" claims have been circulating on the internet, suggesting the British government carried it out in order to stir up public opinion against Russia. Russian propaganda channels have been eagerly promoting that idea too.

In their working paper, Paul McKeigue and Robinson point to a possible British source for the nerve agent. "Porton Down [the British research establishment] must have been able to synthesize these compounds in order to develop tests for them," they say (italics added).

Their claim, though, is simply wrong. Being able to test for a particular compound does not require an ability to produce it.

The working paper is also at pains to question whether Russia could have produced a "military grade" version of the nerve agent, though the relevance of that is unclear. There would be no need to have developed it for battlefield purposes in order to use it against two individuals in Salisbury.

Prof Robinson, who teaches journalism studies at Sheffield, had a busy time last week. He also appeared on both RT and Sputnik talking about the Skripal affair. In addition, his group's working paper about novichoks was featured in an article on Sputnik's website where he was described as an academic "with knowledge of chemical weapons".

Robinson's co-author, Paul McKeigue, is Professor of Genetic Epidemiology and Statistical Genetics at Edinburgh. In a previous publication, McKeigue deployed Bayes’ theorem and probability theory to claim there is "overwhelming" evidence that rebels in Syria used the nerve agent sarin at Ghouta in 2013 and Khan Sheikhoun in 2017. He managed to reach that conclusion even though the sarin used on both occasions was of a type made by the Syrian government and there is no credible evidence that the rebels ever possessed sarin.

Another prominent member of the "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" is Tim Hayward, Professor of Environmental Political Theory at Edinburgh University, who re-posted the article by Robinson and McKeigue on his personal website.

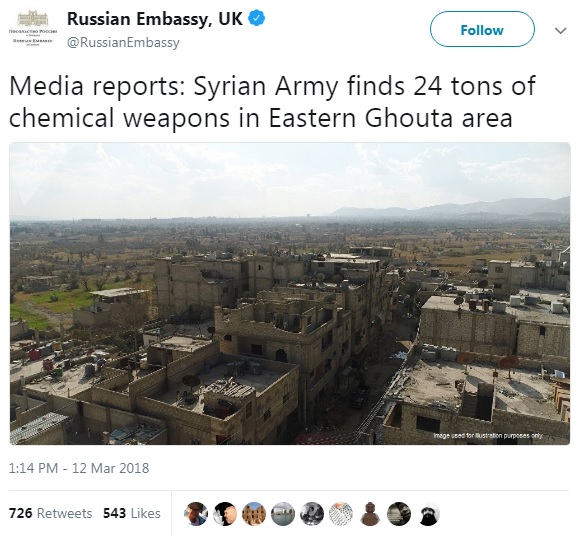

On Monday he re-tweeted a statement from the Russian embassy in London claiming that the Syrian army had found "24 tons of chemical weapons" in an area of Ghouta previously held by rebels.

Hayward commented: "You can see why the British elite do not want us getting any news via Russia" and it was indeed easy to see why – because the Russian claim was demonstrably false.

Various chemicals had been found at what was described as a rebel laboratory but there was no evidence of chemical weapons. Even RT's reporter on the spot, Sharmine Narwani (see previous blog posts here, here, and here) was struggling.

"Is this a chemical weapons lab?" she asked, "Or simply a chemical lab manufacturing a substance used in warfare – like explosives? Even if no banned chemical munitions are found to be produced at this lab, its discovery is a game-changer ..."

Similar stories of "chemical" discoveries have been reported by propagandists in the past with the aim of connecting the rebels to nerve agent attacks. In 2013, for example, RT broadcast clips from Syrian state TV showing poisonous materials allegedly found in a rebel "laboratory". The only identifiable substance in the video was a series of bags labelled as caustic soda produced in Saudi Arabia.

Images of other supposedly sinister rebel-held equipment included medical supplies from a Qatari-German company.

Above: a previous Russian video about a rebel "laboratory" in Syria and (below) medical supplies seized from rebels.

The internet, of course, is awash with spurious claims and fanciful theories but it's disturbing to see university professors joining in and reinforcing that nonsense under the guise of "rigorous academic analysis".

The British government is partly to blame. It has allowed wild speculation to flourish by not being more forthcoming with information about the Skripal attack.

Conspiracy theories tend to be far more interesting than the truth – which is part of their appeal. They also give believers a sense of superiority: by refusing to even consider that mainstream narratives might be correct they can claim not to be fooled by propaganda. But in the process they actually fall straight into the propagandists' trap.

The best defence against being fooled is to look at whatever evidence is available, consider it in the round and apply basic common sense.

Writing for the website politics.co.uk last week, Ian Dunt said:

"Strip it down to its bare bones and you've got a relatively simple situation here. The evidence overwhelmingly points to Russian state involvement. They have the motivation, they have the ability and they have the track record. No-one else does.

"But it is not proven yet and in all likelihood, because of the nature of the operation, never will be. So there is enough doubt for conspiracy theories to blossom and nervy politicians to be frozen by inaction.

"At other times, the obvious story would have defeated the imaginative ones. But we are not living in normal times."

9/11 truther joins Syria 'propaganda research' group

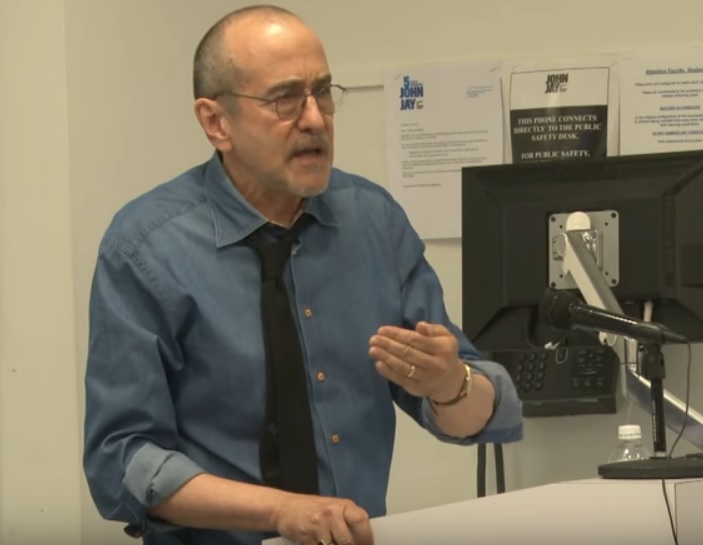

Blog post, 19 March 2018: A group of university professors who claim to be engaged in "rigorous academic analysis" of propaganda during the Syrian conflict have recruited a 9/11 truther to their team.

Mark Crispin Miller, professor of media studies at New York University, rejects what he calls "the official narrative" of al-Qaeda's 2001 attacks on the United States, describing it as "preposterous" and "ludicrous". He also claims that "the meme" of barrel bomb attacks in Syria has been thoroughly debunked.

Miller recently joined the advisory board of the "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media", a group of professors and other academics who, according to their website, have come together to study media reporting of the war and "the role that propaganda has played in terms of shaping perceptions of the conflict".

Along with another professor in the group, Miller has also become a director of a British-registered company called Organisation for Propaganda Studies.

At first sight the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media looks like a genuine – even worthwhile – research project. It talks of producing conference papers and articles and providing "reliable, informed and timely analysis for journalists, publics and policymakers".

On closer examination, though, the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media seems to be not so much countering propaganda as generating it (see previous blog posts here, here and here).

Previously published articles by members of the group cast doubt on their claims of "rigorous academic analysis". They dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation. Several of the group also make frequent appearances on the Russian propaganda channels, RT and Sputnik.

Critical thinking

In his professorial role, Miller teaches a course on "Mass Persuasion and Propaganda" and, as might be expected, encourages critical thought among his students. He urges them to view media with caution and to reflect on what is not reported in the news as well as what is.

But Miller's own fears of mass deception – especially by mainstream media and the US government – have led him to reject what many regard as established fact.

In 2016 he was master of ceremonies at a conference in New York marking the anniversary of the 9/11 attacks. According to its organisers the purpose was to assess "ongoing efforts to expose the truth and obtain justice for the attacks that killed nearly 3,000 innocent victims and that continue to serve as the pretext for the Global War on Terrorism".

In his opening remarks Miller told the audience: "We frankly don't believe the government's conspiracy theory of how that happened ... The official narrative is preposterous. On its face it is a ludicrous explanation. We don't accept it." (See video below at 4 min 19 sec.)

A few months later, Miller spoke at a conference of American leftists on propaganda and "US regime change in Syria". He began by recalling events of a century earlier and "the catastrophic success of the allied propaganda drive that brought the United States into World War One".

The British people and then the Americans, he said, had been"bowled over" by reports of Germans impaling babies on bayonets and cutting the breasts off Red Cross nurses. There was even the story of a Canadian soldier who had allegedly been crucified by Germans.

"This was the first time that a state had ever used resources of mass suasion, of propaganda, to get an entire population to support a war that they ordinarily wouldn't have supported," he said.

Miller went on to draw parallels between propaganda of the First World War and contemporary reporting of the conflict in Syria.

"I don't have to list for you examples of similar atrocity campaigns that we have read about in the western press – Aleppo, various chemical gas attacks, the crematorium –you know, Buchenwald, Auschwitz, right in the middle of Damascus burning up the bodies of all these Syrians ...

"From reading the New York Times or any of its affiliates in the US press, or from watching CNN or MSNBC or listening to NPR you wouldn't know, for example, that the barrel bombs meme was meticulously demolished by Robert Parry of Consortium News ..."

At this, he was loudly interrupted by an angry voice from the audience – the voice of John Davenport, professor of philosophy at Fordham University, who asked: "Are you denying the Assad regime has dropped barrel bombs on its people?"

One person impressed by Miller's performance was Professor Piers Robinson who teaches media studies at Sheffield University in Britain and is now a leading figure in the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media. Robinson posted several tweets saying what a "great talk" it was.

Miller's advisory role with the working group was first made public on March 7 in an update on its website but he already had a formal connection with Robinson which had been established several months earlier. Robinson and Miller are both directors of "Organisation for Propaganda Studies", a Sheffield-based non-profit company which was registered last November. The company has two other directors: Professor David Miller from the University of Bath and Professor Christopher Simpson from the American University in Washington.

The Organisation for Propaganda Studies (OPS) also has a website which is registered in the name of Sheffield University. The website is mostly blank but its "about" page does give some information regarding its plans:

"In addition to research and analysis, OPS activities will include academic conferences and workshops, research funding bids, and the production and dissemination of high quality academic papers and monographs as well as the blog posts, articles in the media and professional outlets.

"The OPS also seeks to develop relations with communication practitioners such as journalists, media professionals, educators, and other stakeholders to facilitate dissemination of research-based knowledge and the reform of professional and ethical practice.

"The OPS website will provide an essential ‘go to’ resource on propaganda, suitable for researchers, practitioners, teachers and the general public, and include links to scholarly publications, projects, and media engagement activities."

It adds that OPS "actively seeks income via donations and consultancy fees as well as research council and other research funding".

Another page on the website lists members of OPS's advisory board. Readers may recognise some of the names:

• Amir Amirani (film/documentary maker)

• Professor Jared Ball (academic)

• Sharon Beder (academic)

• Professor Noam Chomsky (academic)

• Mark Curtis (researcher)

• Professor Robert McChesney (academic)

• Dr Sheila O’Donnell (independent researcher)

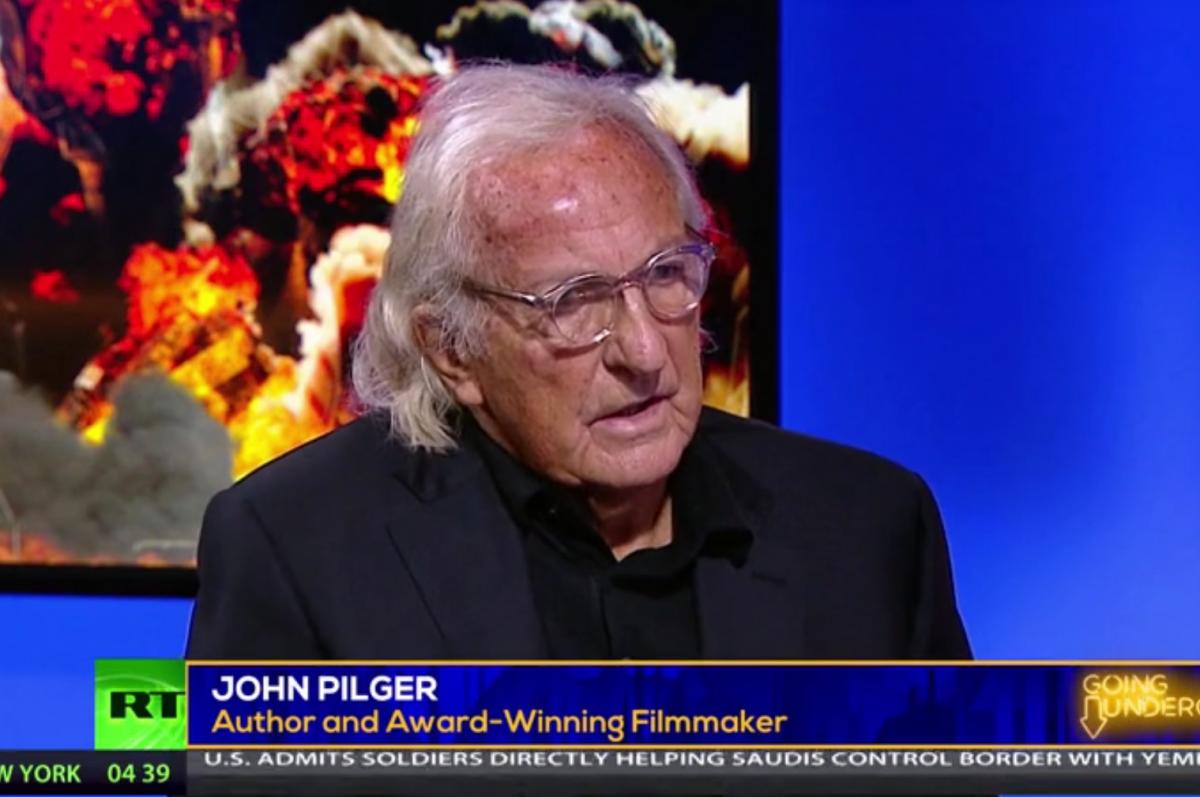

• John Pilger (journalist, film/documentary maker)

• Dr Judith Richter (independent researcher)

Conspiracy theorists seek funds – with backing from university

Blog post, 15 April 2018: A university-based group is seeking funds for what it claims will be "rigorous academic research and analysis of propaganda". The project sounds academically respectable – it has official recognition from the University of Sheffield in Britain and has enlisted the famous American professor Noam Chomsky as an adviser – but it also has links to conspiracy theorists, including a 9/11 "truther".

Last November the group set up a non-profit company called Organisation for Propaganda Studies (OPS). The registration documents say its purpose is to carry out "research and experimental development on social sciences and humanities", plus "higher education" at undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

The group also operates a website – propagandastudies.ac.uk – which is registered in the name of Sheffield University and is hosted on the university's servers. The website is still mostly under development but a note on one page says OPS "actively seeks income via donations and consultancy fees as well as research council and other research funding".

OPS has four directors, all of them professors: Mark Crispin Miller (New York University), Piers Robinson (Sheffield University), David Miller (Bath University) and Christopher Simpson (American University, Washington).

Mark Crispin Miller has become well-known in the US for questioning the usual narratives of al-Qaeda's 9/11 attacks on New York and Washington. "The official narrative is preposterous. On its face it is a ludicrous explanation. We don't accept it," he told a conference in 2016.

He later spoke at a conference on "US regime change in Syria" where he likened reports of atrocities in Syria – including the "barrel bombs meme" – to British and American propaganda during the First World War.

One of his co-directors at OPS, Piers Robinson, posted a tweet describing this as a "great talk".

Robinson, a professor in the journalism studies department at Sheffield, is also a leading figure in the "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" (see previous blog posts here, here and here).

Articles written by members of the working group dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation. While they are critical of western governments, western media and various humanitarian groups they show little interest in applying critical judgment to Russia's role in the conflict or to the controversial writings of several journalists who happen to share their views.

The activities of this group were the subject of an investigation published by The Times newspaper on Saturday. A strongly-worded editorial headlined "Assad's useful idiots" said:

"Some of the academics involved disseminate material that is wrong, unscholarly and morally odious. Their output is no more reputable than the conspiracy theories of the Kremlin and its online trolls. Such material is an insult to the victims of a depraved regime and a stain on the reputation of the institutions which host its authors."

Robinson has decribed the Russian propaganda channel, RT, as a source of "useful insights" and is frequently quoted in its programmes. Another member of the working group, Dr Tara McCormack of Leicester university, has a regular slot on Russia's Sputnik News.

Rather oddly, the only "research" so far posted on the Syria working group's website has been two articles (here and here) casting doubt on a Russian role in the poisoning of Sergei and Yulia Skripal in Britain.

Alongside Noam Chomsky on OPS's "international advisory board" is journalist John Pilger who appeared on RT last month dismissing the nerve agent attack as part of a "propaganda campaign" against Russia. He told viewers:

"You have an attempted murder, you have a crime scene and you have no evidence and neither do you have a motive. Why on Earth would Russia on the eve of an election and on the eve of staging the World Football Cup want to destroy – if you like – its international name with such a crime?"

Before parting with any money, funding bodies would be well advised to take a close look at OPS and consider whether those involved are in the business of producing serious research, or something else.

Syria: logic in a land of make-believe

Blog post, 16 April 2018: I got into an online discussion yesterday with Charles Shoebridge, an ex-soldier and former police officer who disputes the use of chemical weapons by the Syrian regime. One of the questions he asked was why, if the regime was making chemical weapons in secret, it would give the game away by using them. He wrote in a tweet:

"You think that a government pursuing a secret chemical weapons programme would then betray that entire effort by using chemical weapons against some children, at massive political cost and for absolutely no strategic gain? That defies any sense of rationality ... it sounds like clutching at straws."

Questions of this kind probably account for a large part of the skepticism that we see online in relation to the conflict in Syria. There's a lot about the regime's behaviour that doesn't seem to make sense – at least to people raised in western democracies.

It's important, though, to take account of differences in the political culture. Actions that might cause "massive political cost" to a democratic government don't necessarily have the same effect in Syria. For a regime whose primary aim is to retain power by any means, the cost-benefit equation is different.

Put simply, what Charles Shoebridge sees as a problem isn't one that would be likely to bother the Assad regime. A story from a few years ago illustrates this point.

In October 2005 Syria's interior minister, Ghazi Kanaan, was shot dead in his office. There were several reasons why the regime might have wanted to eliminate him, but after a one-day investigation they announced that his death was suicide. The official report stated that the minister had been found lying with a revolver in his hand and his finger on the trigger.

Privately, many Syrians refused to believe the regime's story – and were probably right to do so. But it didn't really matter to the regime, though, whether people believed it or not. The official narrative of suicide served to keep the regime's hands looking clean but the unofficial narrative – of murder or enforced suicide – was useful too: it helped to maintain fear of the regime's power.

In Baathist eyes, even bad PR can have a silver lining. I once had a chance meeting with a Syrian diplomat just a few hours after a bombing in Beirut (for which Syria was being blamed). I asked him how he felt about the allegations against Syria and he replied: "Sometimes, even if you haven't done something, there's no harm in people thinking that you have."

I've been following Syria, off and on, since the early 2000s and I've talked to plenty of Baathist officials. After a while you start to get a feel for the way things work there. What might seem irrational at first often turns out to have an odd kind of logic.

Take, for example, the US-led airstrikes on Friday night which have been hailed in Damascus as a victory for Syria. In the words of one government minister, "We had a double victory, first the clearing of Ghouta and then the air strikes."

"All the Syrians are proud of their army and confident in their president" a member of parliament was quoted as saying. "They know they can resist this sort of attack."

At one cathedral in Syria on Sunday, worshippers showed Christian charity by praying not only for their fellow Syrians but also for the souls of "those who violate international law".

The Assad regime considers itself part of the "resistance" bloc – which generally means resistance to Israel and American influence. Getting bombed occasionally by western powers is a minor inconvenience and, most importantly, it helps to confirm Syria's "resistance" status.

Something similar happened in Libya when President Reagan denounced Gadafy as a "mad dog" and launched a bombing raid which, among other things, partly destroyed Gadafy's house. The remains of the house were carefully preserved as a memento of the occasion and for years afterwards visiting westerners were treated to tours of it.

Syria propaganda and the mysterious 'Sarah Abdallah': a Hizbullah connection?

Blog post, 20 April 2018: Yesterday dozens of Twitter users rallied to the defence of "Sarah Abdallah", a mysterious and possibly fictitious social media celebrity, following what they saw as a smear by the BBC.

A BBC report had identified the @sahouraxo Twitter account – currently operated under the name "Sarah Abdallah" – as one of the leading online promoters of disinformation about Syria.

"Sarah Abdallah tweets constant pro-Russia and pro-Assad messages, with a dollop of retweeting mostly aimed at attacking Barack Obama, other US Democrats and Saudi Arabia," the BBC report said ...

"In her Twitter profile she describes herself as an 'Independent Lebanese geopolitical commentator' but she has almost no online presence or published stories or writing away from social media platforms. A personal blog linked to by her account has no posts.

"Her tweets have been quoted by mainstream news outlets, but a Google News search indicates that she has not written any articles in either English or Arabic."

The BBC went on to say that a study by the research firm Graphika found "Sarah Abdallah" had "one of the most influential social media accounts in the online conversation about Syria, and specifically in pushing misinformation" ...

"The firm found that Sarah Abdallah's account was primarily followed by a number of different interest clusters: supporters of pro-Palestinian causes, Russians and Russian allies, white nationalists and those from the extremist alt-right, conservative American Trump supporters, far-right groups in Europe and conspiracy theorists.

"These groups were instrumental in making the hashtag #SyriaHoax trend after the chemical weapons attack in the rebel-held town of Khan Sheikhoun in April 2017.

"That hashtag, pushed by Sarah Abdallah and influential American conservative activists, became a worldwide trend on Twitter. Many of those tweeting it claimed that the chemical weapons attack was faked or a hoax."

Among those rallying to support "Sarah Abdallah" yesterday was the Russian embassy in South Africa, which tweeted:

Others hailed "Sarah Abdallah" as a source of "authentic" news and an antidote to the coverage in mainstream media. One said:

"The answer to #bbc #fakenews is to follow Sarah Abdallah"

Another said:

"Sarah Abdallah's tweets give more authentic info about Syria than any western media"

The "Sarah Abdallah" Twitter account has 130,000 followers – a surprisingly large number for someone who appears to exist only online, though this may be partly explained by the glamorous photos posted in her name.

Despite her popularity, however, it's hard to find evidence of her life outside social media. Her Twitter feed links to a website, sarahabdallah.net, but anyone who goes there hoping to find examples of her geopolitical commentary will be disappointed. The website (registered anonymously through a privacy protection company in Arizona) is empty apart from a note saying she is "Just a regular Lebanese girl who loves discussing geopolitics and current events. Coffee, books and manga too."

Previous incarnations

Whether or not she's a real person, "Sarah Abdallah" has had previous incarnations on social media. She formerly used two different handles – @jnoubiyeh and @muqawamist – both of which hint at a connection with Hizbullah, the Lebanese shia organisation which is fighting in Syria alongside the Assad regime.

In a Lebanese context, "Jnoubiyeh" indicates a woman from the south of the country, where Hizbullah fought a long struggle against Israeli occupation. "Muqawamist" is a hybrid Arabic-English word. The Arabic part – "muqawama" – means "resistance" and is used in Lebanon to refer to Hizbullah.

A search through the internet archives shows that in 2010 she was running a blog called "South Lebanon". In a profile note on the blog she said:

"I'm a proud Lebanese from Bint Jbeil. We are a hardy and stern people forged by war and the ways of the mountain; perhaps the only inhabitants of Lebanon not to have entirely degenerated into sensuality and decadence.

"I'm a seeker of understanding, lover of truth and despiser of ignorance."

Around the same time she was also running a Twitter account called Jnoubiyeh. The profile note on Twitter described her as "Lebanese from Bint Jbeil, Law student, human rights activist, anti-Zionist, seeker of understanding, lover of Truth and despiser of ignorance". It also said she was living in Montreal and South Lebanon.

There is currently a "protected" Twitter account of the same name, tagged "Beautiful Princess".

"Sarah Abdallah" also blogged for a while under the name "Muqawamist". She deleted the blog early last year, though part of it has been archived by the Wayback Machine.

The surviving content includes several short posts praising the efforts of the Syrian army. There are also pictures of Christians in Aleppo and Homs who have been "liberated" by the regime. Other pictures show Russian troops distributing aid to displaced Syrians. "Sarah" comments: "The EU/US want you to believe this is just a figment of your imagination."

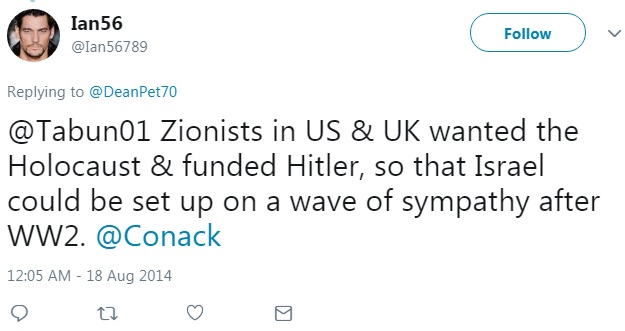

How "Ian56" keeps the false flags flying on Twitter

Blog post, 21 April 2018: Look up Ian56 on Twitter and the first thing you'll see is a fake photograph. The handsome man in the profile picture isn't Ian56. It's a 38-year-old fashion model called David Gandy.

This, plus the fact that Ian56 is a staunch defender of Russia who posts on average 65 tweets a day may have been what led the British government to mistakenly conclude that he was a Russian bot.

In fact, he's neither Russian nor a bot – as his appearance on Sky News confirmed yesterday. He's Ian Shilling, a British bloke with strong opinions who claims there is "zero evidence" of the Assad regime using chemical weapons and believes that "the whole of the official US and UK foreign policy narrative is a complete fabrication and lie".

Ian Shilling's world is one where conspiracies and false flags have become the norm rather than the exception – a world in which even the Holocaust is seen as a Zionist plot. According to one of his tweets, Zionists in the US and Britain "wanted the Holocaust and funded Hitler, so that Israel could be set up on a wave of sympathy after WW2".

Scrolling through Shilling's Twitter feed and his blog it's hard to find a conspiracy theory that he has not at some time supported, but people who casually come across his tweets about Syria and retweet them are unlikely to notice that. They will probably also be unaware that his claims about false-flag chemical attacks in Syria are a close parallel of his claim about a false-flag Holocaust.

Before Twitter was invented blokes like Ian Shilling could often be found perched on a stool in a bar, trying to interest fellow-customers in the latest plot to take over the world. Thanks to Twitter, though, it's now a whole lot easier and they have the potential to be heard by an international audience.

In Shilling's case, this has given him a significant role in influencing public debate. Exactly how much influence he has is something that a US-based analyst known as Conspirador Norteño has been trying to discover.

Conspirador Norteño began by looking at recent use of the hashtag #FalseFlag – most of which has been in connection with the reported chemical attack in Syria.

Out of 58,733 tweets and retweets using #FalseFlag, 11,700 (or 19.9%) were a direct result of Shilling's presence on Twitter (see diagram below). Looked at another way, 11.1% of the 27,090 Twitter accounts using #FalseFlag had done so on the basis of Shilling's initial tweets.

Conspirador Norteño also found that accounts using #FalseFlag were very likely to have used one or more hashtags from other conspiracy theories such as #FollowTheWhiteRabbit, #QAnon, Pizzagate, #SethRich, #SpiritCooking, and #SyriaHoax.

Syria: Why tales of a western 'regime change plot' don't make sense

Blog post, 22 April 2018: There's a claim circulated endlessly on the internet that the conflict in Syria is a "regime change war" orchestrated by western powers. As far as many of the Assad regime's defenders are concerned, this is established fact. To quote one of them – Piers Robinson, writing for the Open Democracy website – the existence of long-standing "western intentions and actions" aimed at achieving regime change in Syria is "not in doubt".

It's true, of course, that there have been calls from western leaders, among them Barack Obama, for Assad to step down – but those were in response to atrocities after the conflict had begun. What the regime's defenders claim is different: that the west had been plotting for years to topple the regime. According to Robinson it's a strategy that "has been in play since 9/11".

Constant repetition of this idea on Twitter along with various "anti-imperialist" and conspiracy websites has helped to give it popular credence even though the historical record does not bear it out.

If you weren't following Syria and its international relations before the war it's easy to be fooled by the regime-change meme. Assad's defenders make it sound plausible by drawing analogies with Iraq, where the goal of overthrowing Saddam Hussein had been official American policy for more than four years before the 2003 invasion. The Iraq Liberation Act, approved by Congress in 1998 (under the Clinton administration) vowed support for "efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq and to promote the emergence of a democratic government to replace that regime".

Mentioning Iraq also brings reminders of the debacle over Saddam's non-existent weapons of mass destruction. We all know that western governments lied about them and used them as a pretext for invading. It's the same with Syria, Assad's defenders say. Western powers, allegedly, are raring to topple the regime and the chemical attacks have been cooked up to provide the excuse.

So far, it sounds fairly persuasive – until you remember there have already been plenty of chemical attacks in Syria and that western powers haven't responded to any of them in the way that the Assad defenders' argument predicts.

When sarin attacks in Ghouta killed hundreds of people in 2013, the British parliament rejected military action. Obama considered it too but pulled back after Syria agreed to join the Chemical Weapons Convention.

Obama's more belligerent successor, Donald Trump, ordered missile strikes in response to the sarin attack in Khan Sheikhoun last year and the more recent chemical attack reported in Douma. On both occasions the strikes were limited in scope and posed no serious threat to the regime. Regardless of his rhetoric, Trump has shown no real inclination to become directly engaged in the broader conflict.

A long goodbye?

But what of the claim that the west had been pursuing a regime change strategy for Syria ever since 9/11 – in other words, for the best part of a decade before the conflict began?

Apart from a short period around 2005-2006, Syria was not a major concern or preoccupation among western governments or foreign policy analysts. In that respect it was very different from Iraq which between the invasion of Kuwait in 1990 and the war in 2003 had been a constant and much discussed issue.

This is not to say that relations between western powers and Syria were good. They were often difficult but had ups as well as downs. The general approach by western powers was to use a combination of pressure and inducements in the hope that Syria would change its ways. In some areas Syria cooperated; in others it did not and the broad picture, on both sides, was one of wary coexistence.

Internally, under the brutal rule of Hafez al-Assad and the Ba'ath Party, Syria had given rise to one of the region's most repressive regimes and, internationally, it considered itself part of the "resistance" to Israel and western political influence in the Middle East.

Syria's grievances against Israel were not without justification, because Israel continued to occupy part of the Golan Heights – Syrian territory it had captured in the 1967 war. Syria, in turn, hosted "political bureaux" of various Palestinian groups, including Hamas, Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ), the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PLFP) and the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command (PFLP-GC). A report by the US State Department in 2005 commented that "Syria's public support for the groups varied, depending on its national interests and international pressure."

Syria's development of chemical weapons was also, at least initially, linked to its disputes with Israel – as a response to the Israeli nuclear arsenal. Chemical weapons were cheaper to produce and were sometimes described as "the poor man's nukes".

Making friends with Bashar

When Bashar al-Assad inherited the presidency from his father in 2000, it was widely seen as a hopeful development. At 34, he was still relatively young and seemed to be a moderniser. Among other things, he was head of the Syrian Computer Society; he made some gestures towards tackling corruption and, for the first time in almost 40 years, allowed publication of an independent newspaper (though it did not survive for long).

Bashar also had connections with Britain. A graduate in medicine, he had spent some time in London doing postgraduate studies in ophthalmology and, shortly after becoming president, he married Asma al-Akhras, an investment banker from a Syrian family who had been born and raised in Britain. Asma was a glamorous figure who attracted media attention and, with the aid of western PR firms, helped to give the regime a more acceptable image.