It was two years ago today that Mohamed Bouazizi, an unemployed street vendor, set himself on fire in Tunisia after police confiscated his fruit-and-vegetables stall.

Expressing regret at this "painful" event, a government official told the Tunisian news agency: "We are outraged by attempts to use this isolated incident, to take it out of its true context and to exploit it for unhealthy political ends."

The unnamed official went on to complain that Bouazizi's protest was being manipulated "into a case of human rights and freedoms" which was "putting in doubt the achievements of development" in Sidi Bouzid (the economically depressed region where Bouazizi lived).

Two years on, it's easy to forget that the disturbances in Tunisia were not the only ones affecting an Arab country at the time. One day before Bouazizi's act of self-immolation, hundreds of Saudi youths had gone on the rampage in the holy city of Medina in what appeared to be sectarian rioting. Early in January, rioting also broke out in Algeria, for reasons that were very similar to those in Tunisia. In Jordan, too, several days of disturbances caused havoc in the city of Maan.

The Jordanian, Algerian and Saudi regimes all survived more or less unscathed and in Tunisia, at least for the first week or so, there was no reason to expect that the outcome would be very different.

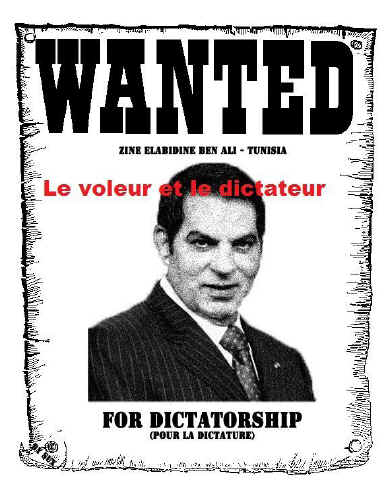

Tunisia was a police state, though the regime had kept its grip more through fear than brute force. Fear – or loss of it – was the key to Ben Ali's downfall. Once the fear barrier began to break down, people came out on to the streets in numbers that the authorities could no longer cope with – and the more the authorities struggled to cope, the more others felt encouraged to join the fray.

The fear barrier had proved an effective deterrent in the past. Precisely why it failed in Tunisia in the last days of 2010 is not entirely clear, though it had certainly been weakened by an accumulation of frustrations and grievances over corruption, repression and the state of the economy – accompanied by a feeling that none of these could be properly addressed while Ben Ali's clique remained in power.

A contributing factor, perhaps, was the release early in December of WikiLeaks documents in which the US ambassador not only described the Ben Ali regime as "sclerotic" but also wrote about the president's family in highly unflattering terms. Much of the information in the ambassador's reports to Washington was already known in Tunisia, but it was something people had previously talked about in whispers; suddenly, though, the WikiLeaks documents brought it into the open.

In comparison with subsequent uprisings, Ben Ali's fall was relatively swift – one month from start to finish – and the scale of violence relatively constrained. It is interesting to speculate whether a more prolonged and bitter struggle in Tunisia would have had quite the same effect across the Middle East but, in the event, it proved inspirational. The first couple of months after Ben Ali's departure brought new uprisings in Egypt, Yemen, Libya, Bahrain and Syria.

All these rebellions reflected long pent-up grievances about the way Arabs were governed. The grievances themselves were nothing new: I had heard many of them expressed eloquently and at length in 2008 when interviewing people for my book, What's Really Wrong with the Middle East, but when I asked what might be done about them, most people at the time could only despair. The effect of Tunisia was to shift that perception; it opened up new possibilities by demonstrating that change was possible after all.

In Egypt, January 25 was a public holiday known as National Police Day. It commemorated the occasion in 1952 when police in Ismailia refused to surrender to British forces and 41 of them died in a three-hour battle. Half a century later, the idea of a special day to celebrate the police – whom many Egyptians by then regarded as oppressors – had begun to seem bitterly ironic.

In January 2010, National Police Day prompted some sarcastic comments (here and here, for example) but little else. So a year later, when the Kifaya ("Enough") movement and the 6 April Youth Movement called for demonstrations to turn National Police Day into a day of "revolution against torture, poverty, corruption and unemployment", interior minister Habib el-Adli didn't seem particularly worried. "Youth street action has no impact and security is capable of deterring any acts outside the law," he said, threatening to "arrest any persons expressing their views illegally".

Adli had perhaps been lulled into complacency by the fact that some of the opposition parties had said they would not be taking part, as had Mohamed Elbaradei, the reform campaigner. Even the Muslim Brotherhood had declined to give the protest its formal backing. A look at Facebook, however, would have shown that more than 80,000 people had declared their support.

In the event, the scale of the January 25 protests exceeded even the organisers' expectations and National Police Day 2011 became Day One of the Egyptian revolution.

Unlike Tunisia before the uprising, Egypt was already well-accustomed to street protests and workers' strikes, though up to that point they had not posed a serious threat to the regime. But during the previous few months two events in particular had intensified public sentiment. One was the case of Khaled Said who died at the hands of the police after being dragged from an internet cafe in Alexandria. The other was the farcical rigged election in November 2010 which resulted, as one newspaper cartoon suggested, in a parliament of cats and dogs.

Without the example of Tunisia, though, it is unlikely the January 25 protests in Egypt would have attracted the support they got – and Tunisian influence was obvious from the start. Someone coined the word "Tunisami" (Tunis + tsunami) and there were chants of "Ya Mubarak, Ya Mubarak, al-Saudia fi intizaarak" – Mubarak, Mubarak, Saudi Arabia (where Ben Ali had fled) is waiting for you.

Today, in contrast to Libya, Yemen, Syria and Bahrain, the revolutions that toppled Ben Ali and Mubarak seem relatively painless affairs without the complications of tribalism, sectarianism, militarisation or foreign interests. Tunisians and Egyptians were able to unite – at least for a while – in pursuit of a single goal: the overthrow of the regime. Subsequent Arab uprisings have proved more divisive and the regimes themselves have fought harder to stay in power.

The politics in post-revolution Tunisia and Egypt has not been plain sailing either – though nobody should have imagined that it would be. Autocratic rule may be undesirable but it does make life simpler, because all the key decisions are made by someone else. How to make decisions in the absence of an autocrat is the question Tunisians, Egyptians and Libyans are now grappling with.

The latest turmoil in Egypt over Mursi's edicts and the constitution are a prime example. Having tasted power, Mursi seems to be hankering after the old Mubarak way of doing things but in a free country government has to be by consent, not submission. There are multiple elements – the Islamists, the military, secularists, Christians, women, etc – all wanting a say. None of them are going to lie down or go away and so they have to be reckoned with and bargained with if Egypt is to move forward. It's a learning curve for everyone – and it's going to be messy and it's going to take time.

It would be a mistake, though, to focus only on Arab countries that have witnessed uprisings aimed at overthrowing their regimes. For ordinary people across the region, the Tunisian example has been enormously empowering. Arabs have begun asserting themselves and reclaiming their citizenship.

Mohamed Bouazizi's humiliation at the hands of officialdom – and his response to it – epitomises this struggle. What Tunisia unleashed was a particular kind of revolution: not so much a tussle for power where one faction tries to supplant another but a largely leaderless revolt against rule by diktat.

We have seen this in the one-word slogans calling for "dignity" and "respect" and, as the Syrian professor Sadik Al-Azm has pointed out, "The people want the fall of the regime" is revolutionary in more ways than one. What "the people want" never counted for much in the past but today no Arab regime can afford to ignore it.

Earlier this month, faced with complaints about his policies on Twitter, the Saudi labour minister decided to meet some of his critics face to face. That may not sound like a big deal but in Saudi terms it was.

In the long run, small changes such as this may prove just as important as the more dramatic events that overthrow dictators. Everywhere across the Arab world people can be found chipping away at the arrogance of power.

What will emerge eventually is a new kind of relationship between governments and the people they govern. It's still a long way off and we can expect plenty of turbulence along the way, but the process itself is probably unstoppable.

Posted by Brian Whitaker, 17 December 2012.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed