The Facebook jihadists

They may not be violent but they are still dangerous

Doing jihad is easier than you think. You can become a soldier in the "Army of Muhammad" in the comfort of your own home, and at no personal risk. All you need is a laptop and a Facebook account.

The internet can – and should – be a battleground for ideas but there are many who treat it simply as a battleground. In a couple of blog posts earlier this week (here and here), I wrote about the activities of some Muslim groups on Facebook which are dedicated to shutting down other Facebook groups run by Arab atheists and secularists.

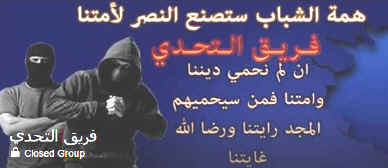

The laptop jihadists are not interested in debating the merits of their beliefs but want to "win" the argument by silencing people who disagree with them. They dress up this pernicious activity in the language of military heroism and defending the Islamic "nation" and glamorise it in one of their Facebook groups with images of a hooded figure and another in a black balaclava.

These groups have succeeded in causing havoc for online atheists and secularists, and probably a good deal of irritation among the moderators at Facebook too. But to regard them merely as a nuisance is to seriously underestimate the problem they represent. Just look at the numbers: one of the groups has almost half a million members and another has well over 400,000.

It's natural, of course, that violent jihadists should be a more immediate concern for governments and their security forces but this can easily lead to an approach where violence, rather than the ideology behind it, is perceived as the main problem.

Those who embrace religious fascism without resorting to physical violence may still cause concern for the authorities but, again, the concern is mainly over whether they might eventually turn violent or induce others to do so.

Thus we have the "conveyor belt" theory of radicalisation which seems to be especially favoured by the British government. The basic idea is that people get on it at one end, while still relatively harmless, and emerge at the other end extremely dangerous. But the conveyor belt is not a particularly good analogy. It suggests an automatic, almost inevitable, process – and while this may be true of some people, there are others who never get beyond the starting point, who reverse their direction or who simply jump off.

Trying to spot those who are on the brink of becoming violent, while necessary from a security point of view, can never be more than a short-term palliative. This violent/nonviolent distinction also misses the point of what jihadism is about. The common factor linking the laptop jihadists with those who resort to guns and bombs is religious supremacism – a conviction that all other beliefs except their own are wrong, and that this entitles them to punish or silence anyone who disagrees. Furthermore, God will reward them for doing so.

When a group espousing such ideas can attract several hundred thousand followers on Facebook it's obvious that some serious work needs to be done – by governments, teachers, preachers, rights activists and, basically, all who value their own freedom of opinion – to promote the concept of tolerance.

However, a major obstacle to this is that many governments around the world (including some considered friends or allies of the west) use religious authoritarianism as a way of maintaining power and silence dissent in much the same way as Facebook's laptop jihadists.

In the Middle East, atheist bloggers have been imprisoned and/or forced into exile: Alber Saber from Egypt, Waleed al-Husseini from Palestine, Kacem El Ghazzali from Morocco. In Saudi Arabia last year, the artist/poet Ashraf Fayadh was sentenced to death for "questioning the Divine Self" – i.e. God. (His sentence has since been commuted to eight years in jail and flogging with 800 lashes, to be administered 50 lashes at a time.) Meanwhile, Raif Badawi, who ran the Saudi Arabian Liberals website is serving a 10-year sentence for apostasy.

Numerous Arab countries have laws against “defaming” religion and in Saudi Arabia “promoting” atheism is classified as terrorism. In five Arab countries – Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United Arab Emirates and Yemen – apostates (Muslims who renounce Islam) can potentially by executed.

Unless these governments change their tune the problem of Facebook jihadists is likely to get worse rather than better.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed