The war in Yemen has been fought almost to a standstill. Four years of military intervention by a Saudi-led coalition aimed at restoring the "legitimate" government have failed to dislodge the Houthi rebels who control much of the north and there's little prospect of doing so in the near future. In the meantime, though, another issue has come to the fore: southern separatism.

North-south rivalries have waxed and waned in Yemen for more than 50 years and the roots of the problem lie even further back, in British and Turkish imperialism.

Aden, on the south-western tip of the Arabian Peninsula, has a natural harbour which in the days of empire was conveniently located as a refuelling post on the sea route to India. In 1839 the British colonised it, later extending their authority to the southern and eastern hinterland, and when they eventually withdrew in 1967 this became the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen – the Arab world's first (and last) Marxist state.

Meanwhile Ottoman forces had conquered the north, installing their own governor in Sanaa in 1871. Turkish rule continued there until 1918 when the Ottoman Empire collapsed. North Yemen was then ruled by imams – religious leaders with monarchical power – until the revolution of 1962 established the Yemen Arab Republic.

With the British gone, aspirations towards uniting these northern and southern republics into a single state became a regular component of the political rhetoric on both sides. Unification talks took place sporadically over more than 20 years – interspersed with periods of conflict – until they eventually agreed merger terms in 1990.

One southern politician who played a key role in unification and its troubled aftermath was Ali Salim al-Bidh whose career might be seen as a metaphor for Yemen's misfortunes. In the space of a few years he governed (not very successfully) in three different Yemeni states and oversaw the demise of two of them.

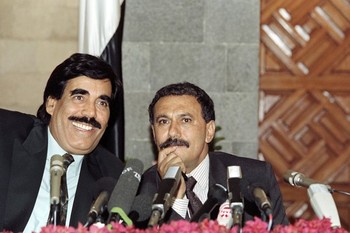

In 1986, following an armed conflict in the People's Democratic Republic which left many of the political elite dead or in exile, al-Bidh emerged as head of the ruling party. The south was in dire straits at the time and in an effort to salvage the situation, al-Bidh concluded a unification deal with the north, then under the wily rule of Ali Abdullah Saleh. Together, the two states became the Republic of Yemen, with Saleh and president and al-Bidh as vice-president.

It proved to be a disastrous marriage and four years later the south attempted to break away again. Al-Bidh then became president of the self-declared Democratic Republic of Yemen with its capital in Aden but the secessionist state lasted only a few weeks before being crushed by Saleh's forces.

As it fell, al-Bidh fled by road to neighbouring Oman – accompanied in the car by his young son, Amr. They have lived in exile ever since and are currently based in Abu Dhabi.

Separatism returns

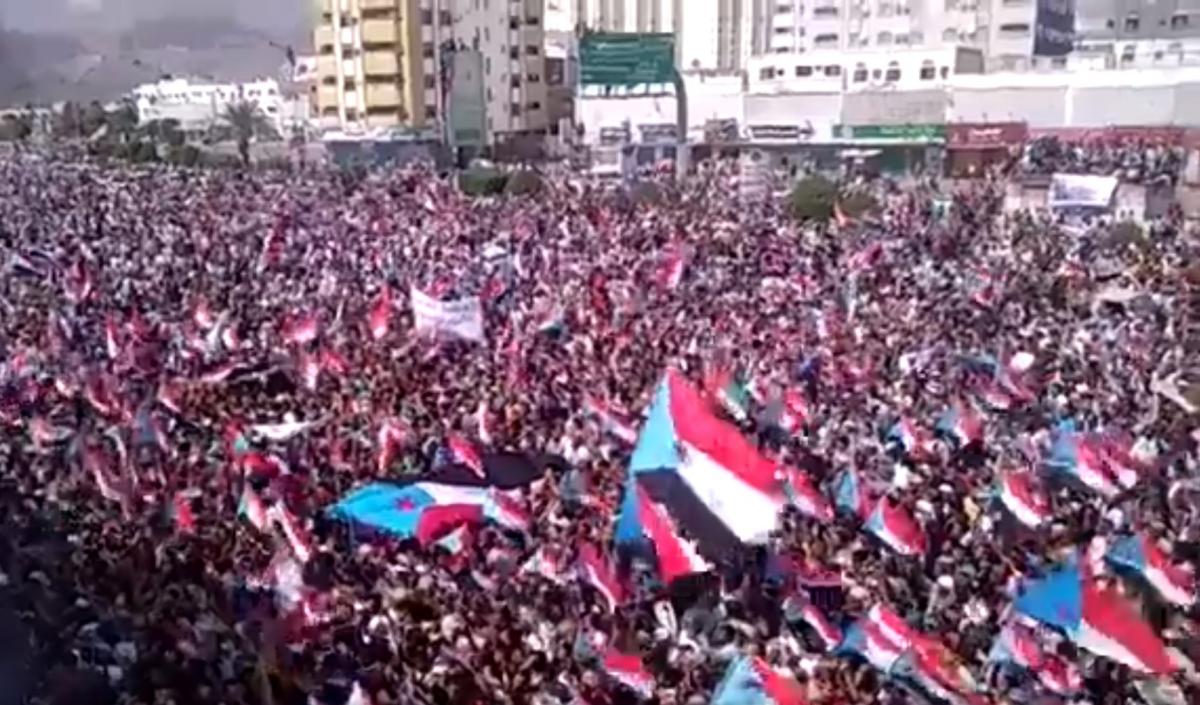

A quarter-century later Yemen's north-south issue is back again with a vengeance and a new generation have taken up the separatist cause. On 10 August they seized control of Aden, ousting supporters of Yemen's internationally-recognised government in a move that appears to have widespread local support. On Friday huge crowds celebrated in the streets, waving flags of the old southern state.

Ali Salim al-Bidh (whose name is variously spelled as al-Baid, al-Baidh and al-Beidh) turned 80 this year and is no longer at the forefront of the struggle. His son Amr is politically active, though, and has been visiting Europe to explain the southern cause. I met him a few days ago in London where he had earlier had discussions at the Foreign Office.

Although southern independence is the ultimate goal, there are three main objectives at present, Amr said – "to preserve security in the south, to provide services for the people and to ask for a delegation representing the south in any political process".

This has profound implications for the Saudi-led coalition. In theory the Saudis, the Emiratis, the ousted government of President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi and the separatists led by the Southern Transitional Council (STC) are all on the same side – fighting the Houthis – but the reality is more complicated.

Since the start of the war the Saudis have focused on bombing the Houthis in the north while the Emiratis have worked in non-Houthi areas – primarily in the south – to bolster local anti-Houthi forces. This had two important side-effects. One was that it created a de facto north-south partitition of the country. The other was that by arming and training resistance forces in the south the Emiratis empowered the separatists.

This in turn has led to conflict between the separatists and supporters of the Hadi government. After being driven out of Sanaa – Yemen's official capital – Hadi claimed Aden as his temporary capital (though he actually spends most of his time in Saudi Arabia). The separatists, on the other hand, say Aden is theirs, not Hadi's. They also accuse the Hadi government of colluding with Sunni Islamist militants – inlcuding al-Qaeda and the Yemeni Islah party – who oppose the Houthis on religious grounds, since the Houthis follow the Zaidi strand of Shia Islam.

Tensions between the Hadi government and the separatists, and between the Saudis and Emiratis, are not new but they came to a head after two separate attacks killed dozens in Aden on 1 August. A missile strike by the Houthis hit a military ceremony involving members of the Emirati-trained southern militia known as the Security Belt, killing Abu al-Yamamah, a prominent separatist commander, along with many others. Earlier in the day a suicide attack attributed to Islamist militants hit a police station.

In response, separatist forces seized control of Aden from the Hadi government's forces which they accused of failing to provide adequate protection. This confrontation was not unexpected – according to Amr al-Bidh it was just a question of time, and the 1 August attacks provided the necessary spark.

Since then there have been calls for the separatists to withdraw but Amr thinks that is unlikely to happen. "Withdrawing would be hard now. It's a matter of security," he said. The Emiratis have invested a lot in establishing the local southern forces and despite Saudi complaints about their takeover of Aden withdrawing support for them would probably make the situation worse.

Amr also views the southern forces as a key element in the coalition, and the most effective anti-Houthi force on the ground. "We are the only ones who are fighting now in Dali' with the Houthis – we've pushed them back," he said. "We [rather than the government] are the ones who are fighting al-Qaeda in Shabwa," he added. "We are the real effective element to fight those kinds of Islamists."

The separatists' basic claim is that they are better placed than anyone else to provide security in the south, and should be allowed to do so. But there is more to the security issue than security itself. If the separatists can establish control of security across the south and start to provide services for the public they will have the rudiments of a future state.

More immediately, control over security in the south would give the separatists significant leverage in discussions about the post-war shape of Yemen – a process from which they currently feel excluded. The problem at an international level, as the southerners see it, is that the Yemeni war is treated as a two-sided conflict – Houthis versus the "legitimate" government.

An illustration of this came on 6 August when the STC's president, Major General Aidarus al-Zubaidi, met Martin Griffiths, the UN's special envoy, and asked for the southerners to be represented in the peace process "as a principal and independent party". According to Amr, Griffiths said he would pass on the request but could not promise anything because it was outside his mandate.

Amr added that this was Griffiths' first meeting with the STC in months and suggested such contacts are a deliberate tactic – periodically drawing the southerners closer to the politicial process to put pressure on the other parties, then pushing them out again: "Maybe they are just using us to threaten the two sides to sit and talk."

Amr has a chart on his iPad showing the various steps in the UN's peace plan – a plan which he says should be revised in the light of "new facts on the ground" in the south. The current aim of the plan is to establish a transitional government and a national military security council. This would be negotiated between the Houthis and the Hadi government – the southerners would not be brought in until a later stage, as part of "inclusive political talks."

There are obvious reasons for that approach. Ending the war is seen as more urgent than addressing the southerners' demands. Internationally, there is also little support for separatist movements. When Amr's father led the short-lived secession in 1994 the only country to recognise it was Somaliland (itself a recently-declared state unrecognised by the rest of the world) and I asked him what international support the separatists are getting now – apart from the Emiratis' apparent backing.

"That needs work," Amr said. "People think these kinds of [separatist] projects are failures. It's not a rosy thing to talk about, especially after the South Sudan situation. We have problems in Europe with Catalonia. [People] say they don't want to open the door – they don't like these kinds of projects. We need to do more work to convince the international community."

In the meantime, though, continued international support for the Hadi government looks increasingly difficult to justify. Whatever legitimacy it had in the beginning has mostly evaporated. Hadi – formerly President Saleh's deputy – never had much of a power base and was elected to succeed Saleh in a "contest" where there were no other candidates. This was unconstitutional but it was supposed to be only for a two-year transitional period. Seven years later, though, Hadi is still there. Another strand of the "legitimate" government is a rump parliament last elected 16 years ago.

But what of the separatists' legitimacy? They appear to have plenty of local support though they have not been in a position to demonstrate it electorally. "This is a problem in the southern movement from 2007 until now," Amr said. "We don't have institutions, so we say the STC is representing the southern cause but not the southern people. If you want to represent the whole people you need elections, a referendum ..."

In any eventual negotiations he envisages the south being represented by an inclusive delegation: "You need to bring in more people in order to strengthen your base." This would mean striking deals with tribal leaders and other dignitaries but he doesn't see them as part of the negotiating team. "The delegation needs to have specialised people for negotiating but we have to sign agreements with other figures, different components in society – we have to bring them all together so that the delegation represents all these people."

Such talk may be premature, though, because the STC isn't welcome everywhere in the south. "It's a mixed situation," Amr said.

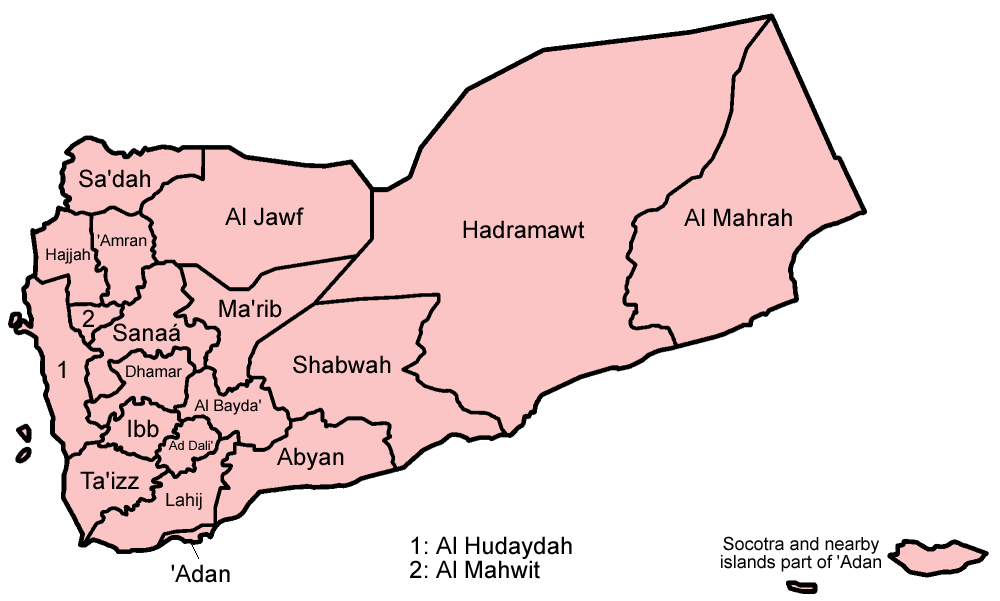

The northern part of Hadramaut province, for example, is controlled on behalf of the "legitimate" government by Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar, an army general who Hadi appointed as vice-president in 2016. Most of the al-Qaeda and ISIS militants are based in that area too, according to Amr.

Two problem towns in other parts of the south are Beyhan in Shabwa province and Mukhayras in Abyan. The latter is controlled by the Houthis and ousting them is difficult because of the mountainous terrain.

There are also some potential difficulties in al-Mahra – the south's most eastern province bordering Oman. "It's very sensitive," Amr said. "Omanis are working there ... and also the Saudis have their military there. Maybe we need to talk to them about how to handle the situation."

The impulse towards separatism

Following the unification of Yemen in 1990 separatist sentiment was driven mainly the Saleh regime's ill-treatment and exploitation of the south. When Saleh fell and the Houthis seized power in Sanaa the focus switched and the separatists' main selling-point became freedom from Houthi rule.

One question this raises is what effect southern independence would have on the north: would it weaken the Houthis or strengthen them? The current peace plan envisages a single (and probably federal) Yemeni state where the inclusion of the southerners would presumably help to dilute Houthi influence.

In Amr's view, though, this won't work. He argues that the south needs a border to keep the Houthis out:

"If there is a government in one country we are giving space to the Houthis to come back to the south – through security, through politics. If you make a federal state they will come ... They can go back to Aden and work there - they [will] have the right to do it. They'll be back to politics in those areas and the Houthis are very desperate. When they come back, they come hard ... they come with businessmen, they come in different ways.

"If you have the same country you can't make sanctions against them, because we will be affected in the south and other areas, so it's better to squeeze them." The same would apply to any aid or support for a united Yemen from other countries, he added. "It has to be shared with everyone, so this will help the Houthis. The best thing for us is to isolate them."

Isolated though the Houthis might be, their continued rule in the north – for several more years at least – would be the likely result and I asked Amr how their Saudi neighbours would react to that.

"The Saudis will have a shorter border to deal with," he said.

This is true, because after separation more than half the thousand-mile border would be shared between the Saudis and the southern state – not with the Houthis. What Amr didn't mention is that separation would also give the south a long and porous border with the northern Yemen which it will have to police if it wants to keep out "Houthi businessmen" and other undesirables (see map).

A further complication is that the southerners are seeking to create their state within the colonial borders established in the 1960s for the People's Democratic Republic. While war has divided Yemen, very roughly, along similar lines, the division between Houthi and non-Houthi areas doesn't precisely follow the boundary between the old northern and southern states. For example, Marib province was part of the former northern state but is not under Houthi control.

I asked Amr if Marib might be invited to join a future southern state.

"Right now we focus on our lands, how to preserve these southern provinces," he said. "For sure there will be a relationship with that part of the country [Marib] but it needs to be developed in a proper way.

"In the future, I think they are better to deal with Sanaa rather than to deal with us. We need a place [in the north] that's not 100% Houthis. That's crucial and important."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed