Saudi Arabia's high-speed railway linking the holy cities of Mecca and Medina took 10 years to build and cost more than $16 billion. It was meant to be a triumph of design and engineering but on Sunday, less than a year after carrying its first paying passengers, the line was shut down when one of its stations caught fire.

Shortly after noon, a huge cloud of black smoke rose over the city of Jeddah as the station's roof burned. Firefighters – some of them using helicopters – took around 12 hours to bring it under control.

No deaths have been reported but Saudi officials say 11 people were injured. A large part of the station's concourse was severely damaged and the entire 450-km Haramain line is expected to stay out of action for at least a month.

The cause of the blaze is still unknown but it's clear from the way it spread that the roof had been constructed without adequate fire resistance. It's also clear from photos and videos that laminated roofing panels were at the root of the problem.

The main contractor on the Jeddah station project was the now-bankrupt Saudi Oger company headed by Lebanese prime minister Saad Hariri. Instead of buying the roof panels from a specialist firm, as contractors on some of the other stations did, Saudi Oger decided to make them itself.

Modular design

In 2009 two British firms – Foster+Partners, the award-winning architects, and consulting engineers Buro Happold – were commissioned to design the first four stations on the line: in Mecca, Medina, Jeddah and the King Abdullah Economic City.

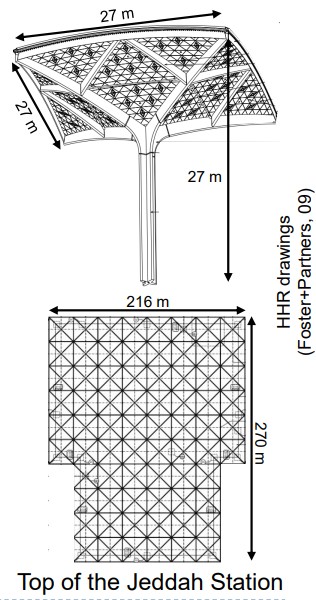

They came up with a similar design for all four stations, based on a module 27 metres square. One benefit of this was that the modules could be pre-fabricated and then joined together on site. It also meant the stations could be easily expanded in future by adding more modules as the volume of traffic on the line increased.

Describing this arrangement, Foster+Partners said:

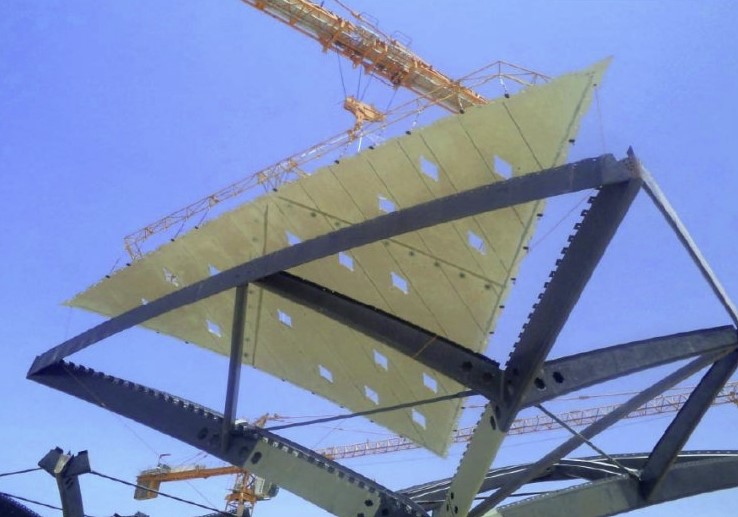

"The steel columns and arches [of the modules] form freestanding structural trees that are repeated on a square grid and connect to form a flexible vaulted roof, inspired by the colonnades found in many traditional buildings in the region."

The diagram below shows one of the modules and how they were to be combined to form the concourse of the Jeddah station.

The roof/ceiling of the concourse consisted of curved laminate panels, triangular in shape, fitted over the steel arches.

All stations on the Haramain line are roofed with similar panels. They have rarely, if ever, been used on such a scale for architectural purposes: together, the four stations have 160,000 square metres of them.

One question this raises is whether the other stations on the line pose a similar fire risk. If so, the Saudis have a major problem on their hands and the line could be closed for a long time while remedial work is carried out.

However, not all the panels came from the same source – which raises the question of whether they were all manufactured to the same standards. If not, this could be a significant factor.

Contracts awarded

Early in 2011 the Saudi government awarded construction contracts for the first four stations on the Haramain line. Those for Mecca and Medina went to a consortium headed by the Saudi Binladin Group and the other two – for Jeddah and the King Abdullah Economic City, worth a total of $1.2 billion – went to Saudi Oger.

One member of the Binladin consortium was Yapı Merkezi, a Turkish firm, which commissioned the Dubai-based Premier Composite Technologies to make the roof panels for Medina.

Premier Composite Technologies worked closely with a Swiss company, Gurit, to develop the fibre-reinforced plastic (FRP) panels. Gurit's role was to provide "structural analysis and optimisation" of the panels, and its website gives some technical details:

"Materials chosen for the laminating of the panels were Ampreg 21FR, a fire retardant epoxy laminating system, Spabond 340LV structural adhesive and G-PET 75 FR LITE, a lightweight, fire retardant, closed cell structural foam core."

It's clear from this that they were paying attention to fire safety, though the website does not say what tests were carried out. Determining whether a material is "safe" is a complex business and even those described as "fire retardant" can burn vigorously under some circumstances. The basic aim is to ensure that if they do catch fire they will burn slowly enough for people to escape and will not poison them with the smoke.

Doing it themselves

Meanwhile, in Jeddah, Hariri's Saudi Oger company decided to make its own roof panels. There's an account of this in the March 2104 issue of Gurit's corporate magazine (pages 22-23) which describes it as "quite a unique approach".

Saudi Oger's project manager for composites, Souhail Alla, told the magazine:

"We are responsible for the complete construction of the Jeddah station. Rather than contracting the manufacture of the composite roof panels out, we decided to bring this key manufacturing process in-house, as we believe there is great future for composites in architecture."

To that end, they set up new a production facility in Jeddah specially to manufacture the station's roof panels.

Explaining this decision, Alla said: "When you have to cover some 55,000 square metres logistically this makes a lot of sense. This is an area of around eight football fields. We don’t have to transport bulky elements long-distance – a huge advantage."

The Jeddah station was not Saudi Oger's first venture into the composites business. It had previously constructed a very large dome for the Princess Nourah University in Riyadh. On that occasion Gurit had supplied some of the materials and helped with engineering aspects.

Setting up production for the Jeddah roof panels was "quite a big challenge", the magazine said, because "many process aspects called for first-time innovative answers".

It meant developing special machinery and equipment, including overhead cranes – all of it produced in-house by Saudi Oger, according to the magazine.

Some technical help was provided by a French company, Méca, which appears to have been mainly concerned with ensuring the panels were strong enough.

Méca's website notes that the fire specification was ASTM E84 (which checks for surface burning), with a flame index below 250 and a smoke index below 450, but it gives no details about actual testing.

End of the line for Saudi Oger

As it turned out, Saudi Oger never completed the Jeddah station. In 2016 it ran into financial problems, stopped paying thousands of its workers and eventually went bankrupt. The Turkish firm Yapı Merkezi was then called in to finish the job.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed