By Brian Whitaker

Published 17 September 2024

The Gaza war has long tentacles. In Britain, art galleries and concert halls are becoming part of the battleground. Cultural events that give voice to Palestinians or support their right to nationhood are under attack from pro-Israel campaigners seeking to suppress them.

With an ever-growing list of atrocities in Gaza it might seem perverse to be worrying about cancelled music performances, hastily rescheduled film screenings and the removal of pictures from exhibitions, but in a way they are fundamental. Expunging Palestinian heritage is the cultural equivalent of genocide.

War de-humanises, and in Israel’s narrative Palestinian farmers, nurses, engineers, teachers, shopkeepers and taxi drivers all merge into a single identity as terrorists. They are openly likened to “cockroaches”, “vermin” and “a cancer” — the language of genocide.

In contrast to that, culture humanises. It tells us that in the midst of the carnage there are still people with thoughts, feelings and a culture who just want a normal life.

Singing to exist

For exiled Palestinian singer Reem Kelani the point of her music is not to make money or become famous but simply to show that she exists:

“When you deny my existence it is a lot worse than victimising me. When you victimise me, you acknowledge that I’m there … But if you deny my music, you deny my existence.”

Kelani’s material includes traditional Palestinian songs and sometimes poems, with a jazz-influenced accompaniment using Arab and western instruments. Last May she was due to give a concert at St Luke’s church in Bath but a month before the event the booking was abruptly cancelled.

This was not an isolated incident. Similar things are happening at venues—large and small—up and down the country ... and there's a pattern to them. Kelani's concert had come to the attention of a group called UK Lawyers for Israel (UKLFI) which wrote to the Bishop of Bath and Wells, to the Archdeacon and to the church itself, demanding the concert’s cancellation.

UKLFI (see previous articles) makes a speciality of sending complaint letters about activities it disapproves of, usually claiming they are breaking the law. The purpose, according to its website, is to combat “attempts to undermine, attack and/or delegitimise Israel, Israeli organisations, Israelis and/or supporters of Israel”.

When it comes to concerts, St Luke’s church in Bath isn’t exactly the Albert Hall but you might think it was, considering UKLFI’s persistence in trying to sabotage Kelani’s performance. In an account on her blog, she says that following the cancellation by St Luke’s UKLFI sent warning letters to other churches in the area in case they were thinking of offering her an alternative venue.

Eventually, Bath’s historic Pump Room, owned by the local council, came to the rescue but that was not the end of the problems. The Pump Room faced further interventions from UKLFI, Kelani says, leading to discussions with councillors and the police that resulted in the concert going ahead under several stipulations — one of which was that by 12 noon on the day of the performance the organisers must provide the names of everyone who would be attending.

Meanwhile, since the event had been rescheduled, Kelani’s usual band was no longer available and the concert ended up as a duo with just Kelani and pianist Bruno Heinen (who happens to be Jewish).

UKLFI sought to justify its interference on the grounds that Kelani had posted “divisive, inflammatory, misleading and offensive comments” on social media regarding the war in Gaza. “If such statements were repeated at the event, they would potentially commit offences contrary to the Public Order Act 1986,” UKLFI said — adding that even if they were not repeated, hosting the event could still be seen as an endorsement.

UKLFI claimed that in posts on X/Twitter Kelani had “falsely” accused Israel of genocide (“falsely” because UKLFI insists there’s no evidence of genocide). It also claimed Kelani had “compared Israel” to Josef Mengele, the notorious Nazi doctor. The Mengele comparison actually referred to Israeli pathologist Yehuda Hiss, who had been involved in a scandal over the harvesting of body parts without relatives’ permission. A look at Kelani’s timeline shows she had also used the Mengele label before — referring to Syria’s doctor/dictator Bashar al-Assad.

Kelani’s manager, Chris Somes-Charlton, suggests she was targeted mainly for her role in keeping Palestinian heritage alive:

“When Reem sings, say, a 19th century song from the Galilee, she is reminding her audience that the Palestinians were always there in Palestine, long before Israel was a glint in any settler’s eye. It’s the narrative of Palestine and of the Palestinians which makes artists like Reem a particular target.”

Her 2016 album, Sprinting Gazelle (reviews here), is an emphatic statement of Palestinian cultural heritage, he says. “Half of the songs are Reem’s unique arrangement of traditional songs, the other half, her musical settings of poems by prominent Palestinian poets.”

Sprinting Gazelle is recommended as an example of World Music in the British government’s Model Music Curriculum for schools.

Bristling in Bristol

The deadly attack on Israel by Hamas on October 7 and the ensuing full-scale war prompted various organisations to review their plans for Palestine-related events. On November 21, the Arnolfini — billed as Bristol’s international centre for contemporary arts — said it had taken a “difficult decision” not to host two scheduled events connected with the annual Palestinian Film Festival.

A statement said it was worried that the events might “stray” into political activity or be construed as doing so. The Arnolfini is a registered charity, and although charities can — and do — engage in political activity the guidelines set by the Charity Commission are complicated. The arts centre said that although it was legally obliged to follow this guidance it lacked the resources to carry out adequate risk assessments.

One of the cancelled events was a poetry evening headlined by the rapper Lowkey. The other was a showing of Farha, a film made by Jordanian-Palestinian director Darin Sallam which had premiered at the Toronto International Film Festival in 2021. Both events went ahead at alternative venues (also registered charities) but the Arnolfini found itself facing a backlash.

Artists and performers announced a boycott, sit-ins took place and more than 2,300 people signed an open letter questioning the Arnolfini’s explanation that it had been worried about “straying” into politics. The letter cited previous events with politically contentious themes that the Arnolfini had hosted, apparently without similar concerns.

The boycott ended five months later when the Arnolfini responded with a grovelling mea culpa:

“The ongoing devastation and loss of life in Gaza, the West Bank, East Jerusalem and Israel is abhorrent … During this overwhelming humanitarian crisis, the voices of the victims need to be heard. Arnolfini recognises the importance of artists and their powerful voices in a complex world. We believe that freedom of expression and intellectual freedom are vital and must be fully reflected in our policies and practices. We are sorry that we did not provide a platform for Palestinian voices at such a crucial time.”

UKLFI condemned the apology, saying it demonised Israel and failed to recognise the rights of Jewish people in Bristol.

Farha, the film at the centre of the tussle is set in 1948 during the mass displacement of Palestinians known as the Nakba (“Catastrophe”). Farha (Arabic for “Joy”) is the name of its central character — a 14-year-old girl who finds herself trapped in her family house, hiding from the Israeli military.

Films about the Nakba are by no means uncommon — it’s a recurrent theme among Arab film-makers — but Farha appears to have been singled out for suppression because it was getting too much international attention: it had won several awards and was chosen as Jordan’s entry for the 2023 Oscars. A campaign against the film began in Israel towards the end of 2022, coinciding with its release on Netflix. Hardline finance minister Avigdor Lieberman and culture minister Hili Tropper both condemned it and Netflix came under pressure to stop streaming it.

Dangerous graphics

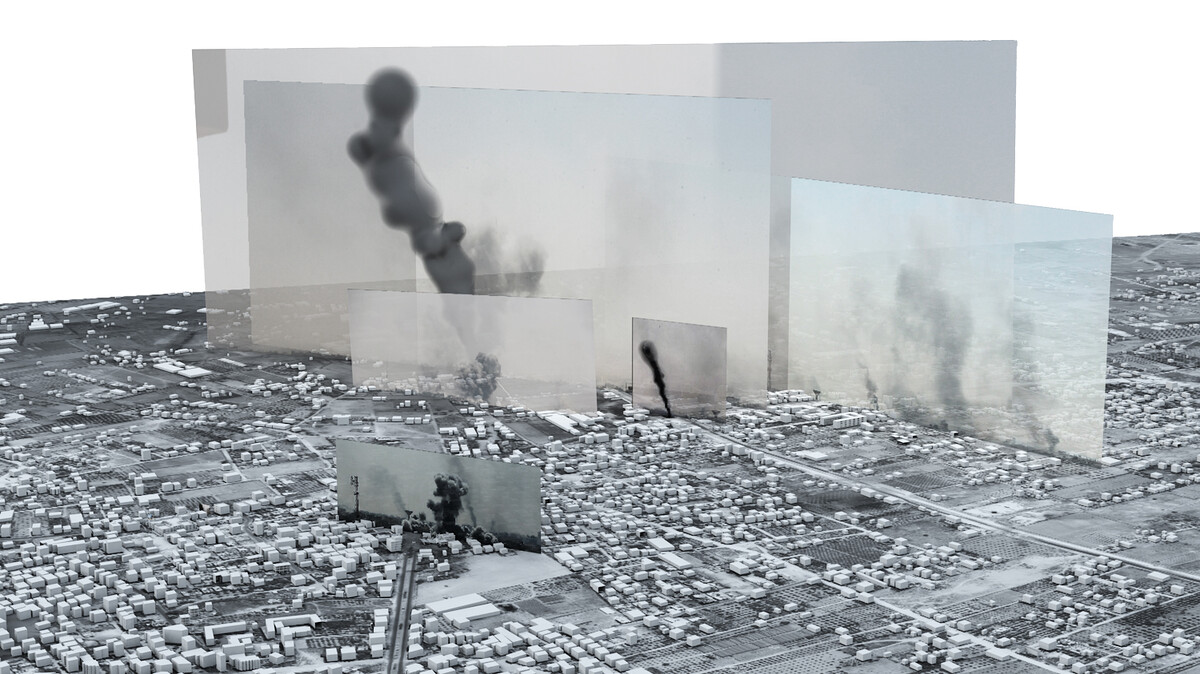

A raised public profile also contributed to the targeting of Forensic Architecture, a research group at Goldsmiths, University of London, which uses graphical techniques to investigate and reconstruct incidents of state violence and human rights violations.

Its techniques have been widely hailed as ground-breaking. Notable examples of its work include visual analysis from the scene of attacks during the conflict in Syria and a reconstruction of the police shooting of Mark Duggan in London in 2011.

Following Israel’s seven-week bombing of Gaza in 2014, Forensic Architecture worked with Amnesty International to create the “Gaza Platform” — “a unique database of satellite imagery, broadcast news and citizen generated footage, stills, tweets, press reports and releases generated during the conflict and provide a definitive picture of what happened minute by minute, hour by hour, day by day, as a way of investigating war crimes”.

In 2018, after being displayed in several exhibitions, the Gaza Platform was unexpectedly shortlisted for the Turner Prize for visual arts. The prize has a controversial history and its judges often make provocative choices.

A few days before the judging, UKLFI wrote to the director of Tate Britain (which organises the award) claiming that the content and methodology of the Gaza Platform were “wholly lacking in objectivity and integrity” and “amounted to modern blood libels likely to promote antisemitism and attacks on Jews”.

It warned that giving the prize to Forensic Architecture would “result in further publicity being given to these lies” and urged the judges to take that into account when making their decision. The eventual winner was Charlotte Prodger whose work “explores issues surrounding queer identity, landscape, language, technology and time”.

Clouds over Manchester

Forensic Architecture’s near miss in the Turner Prize meant it was already on the radar when a further collection of its work went on display at the Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, in 2021.

The exhibition was called “Cloud Studies” but the clouds weren’t there to look pretty: they were the sort of clouds caused by bombs, tear gas, chemical emissions, herbicides and forest arson. A video included in the exhibition focused on a stretch of the Mississippi river where slave plantations have been replaced by petrochemical industries polluting the air. Another showed scenes from Israel’s bombing of Gaza in 2008 and the black smoke from tyres set alight by Palestinian protesters.

UKLFI wrote to the Whitworth’s owner — Manchester University — objecting to what it said was “inflammatory language, portraying Israel as an occupation force engaged in ethnic cleansing, apartheid, human and environmental destruction”. The letter went on to accuse the university of neglecting its legal duty under the Equality Act “by not considering the impact of the inflammatory language” on Jewish people in Manchester.

Shortly afterwards, Forensic Architecture learned via UKLFI’s website that a statement of solidarity with the Palestinians, displayed at the entrance to the exhibition, had been unilaterally removed. Forensic Architecture responded by threatening to pull the whole exhibition and the solidarity statement was put back on display, this time alongside a counter-statement from the Jewish Representative Council of Greater Manchester asking visitors not to assume anything in the exhibition was true.

The Guardian later reported that Manchester University was demanding the resignation of Alistair Hudson, the gallery’s director, over his handling of the affair. He left at the end of 2022 to take up a new post in Germany.

Random targets

Some of the other targets chosen by pro-Israel activists appear far more random. One obscure event that UKLFI tried to stop was a meeting of Marxist psychotherapists to discuss a book titled Psychoanalysis Under Occupation: Practising Resistance in Palestine.

On at least two occasions, events that drew complaints when held in one location have escaped the attention of objectors when repeated elsewhere: a lot depends on whether Israel’s supporters happen to notice them. A collection of art by Palestinian children depicting everyday life in Gaza was displayed on a wall at the Chelsea and Westminster Hospital for 11 years but was summarily removed earlier this year after Jewish patients reported to UKLFI that it made them feel “vulnerable, harassed and victimised”.

Although other Jewish organisations sometimes take up complaints directly, UKLFI has established itself as the main channel for tip-offs from individuals: they provide the initial information and UKLFI takes over from there. Occasionally, though, there are individuals who cut out the intermediaries and take up cudgels themselves.

Horrors at the Royal Academy

“I helped chalk up a small victory yesterday in the struggle against antisemitism,” columnist and author Melanie Phillips announced in a blog post last July. She explained:

“A friend drew my attention to the catalogue of the Young Artists’ Summer Show at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, which opens today.

“The exhibition showcases art works, mainly paintings and sculptures, by children and young people aged four to 19. Most of these works are, as you would expect from such young people, sweet, naive and innocent. There are self-portraits, works depicting family members, animals, food and, among the older children, thoughtful meditations and flights of fancy.”

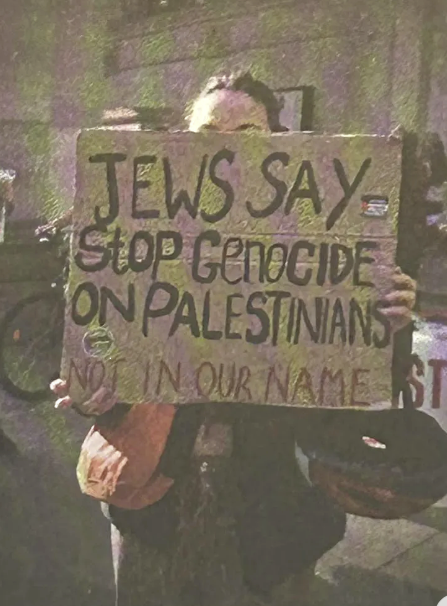

However, one “horribly jarring” exhibit from an 18-year-old prompted Phillips to send an angry email to the Royal Academy. It showed a person holding a cardboard placard with the words: “Jews say stop genocide on Palestinians. Not in our name.” Sharp-eyed Phillips also spotted two tiny stickers on the cardboard with the words “genocide” and “apartheid”.

This, she informed the Royal Academy, was deeply divisive, offensive and threatening towards Jews — and “a vicious lie”. There is no genocide of the Palestinians, there is no apartheid in Israel, she wrote, and the only Jews who would support the placard’s message are “a few cranks”.

“Does the Royal Academy really think it appropriate to hang this message of hatred and incitement in a show which will probably be viewed by young people and is deeply divisive, offensive and threatening towards Jews?” she asked.

While awaiting the Royal Academy’s reply, Phillips — a staunch defender of Israel and author of Londonistan, a scare-mongering book about Muslims in Britain — spotted another problem. It was a charcoal drawing of three anguished women in headscarves with a sinister-looking figure on either side of them and a looming Buddha figure in the background marked with a swastika. An explanatory note from the 16-year-old artist said:

“I have created this piece of work inspired by the recent conflict in Gaza. For me, art is about voice — expressing myself, unapologetically. Watching the conflict unravel in Gaza draws many parallels with the Nazi’s [sic] and Chinese oppression, hence the Buddha symbol and the swastika. I wish for peace; I wish for a better world.”

(Note: Besides being a Nazi symbol, the swastika is used in Buddhism, the largest officially recognised religion in China.)

The Board of Deputies of British Jews also complained about the pictures (though in more moderate language than Phillips) and both were promptly removed from the exhibition. Explaining its decision, the Royal Academy said:

“We recognise that an exhibition for young people and artwork by young people is not an appropriate environment for volatile public discourse … Having reviewed and considered the matter carefully, we feel that by continuing to display these artworks, with limited opportunity to provide context or discourse, we would risk causing undue upset and could put people at risk … We apologise for any hurt and distress this has caused to our young artists and to our visitors.”

The Artists for Palestine group then responded with an open letter carrying almost 800 signatures which said:

“Many of us have joined the Jewish bloc at marches in London that have called for a ceasefire in Gaza. By censoring a photograph of a protester with a placard reading, ‘Jews say stop genocide on Palestinians. Not in our name’, the Royal Academy has colluded with the erasure of Jewish contribution to solidarity with Palestinians.”

Dithering over diaries

The HOME arts centre in Manchester boasts of working with international and British artists to produce “an exciting mix of thought-provoking film, art, drama, dance, and festivals”. The aim, it says, is to push boundaries, experiment and take risks.

Risk-taking and boundary-pushing suddenly dropped off the agenda last March, though, when a local Jewish organisation objected to a forthcoming event and HOME agreed to cancel it.

The event in question was “Voices of Resilience”, billed as a poignant evening of Palestinian writing and poetry, accompanied by live oud music. It was to feature readings from the diaries of Gazan writer Atef Abu Saif and the organiser was Manchester-based Comma Press which had published his diaries in book form.

Abu Saif is a writer of some repute — one of his novels was shortlisted for the Arabic Booker prize — and he’s a former culture minister of the Palestinian Authority. According to the Jewish Representative Council of Greater Manchester he is also an antisemitic Holocaust denier, though Comma Press insists that he is not.

HOME said it was cancelling Voices of Resilience “in the face of recent publicity” because the safety of staff, audiences and artists was paramount.

At this, 300 people signed a protest letter, demonstrators gathered outside the building and numerous artists withdrew their work from an exhibition. HOME then had a change of heart and cancelled the cancellation.

Voices of Resilience finally went ahead on 22 April under tight security. Reviewing the event for a literary website, Jessica El Mal described the scene:

“On the day of the event HOME’s entire building was shut down, with the foyer, bar and shop areas closed and left in darkness. All other events and screenings scheduled that day were postponed or cancelled.

“Barricades were put up outside the venue and before audience members could enter the building, they were required to show photo ID to the private security staff hired specially by HOME for the night. They searched bags, removing aerosols and liquids. All the bins had been removed from the foyer. Police were also present.”

A second performance of Voices of Resilience took place at the Edinburgh International Book Festival in August and on that occasion it seems to have escaped the attention of objectors. “The Edinburgh event went fairly smoothly, and if there were any complaints, we weren’t privy to them,” Ra Page, Comma Press’s chief executive, said.

Meanwhile, a third performance was scheduled for 14 September at the Barbican arts centre in London.

A chilling effect

Most of the time UKLFI’s legal threats don’t stop cultural events from taking place but they do force organisers to waste time (and sometimes money) rearranging them. The main benefit for Israel lies in the general chilling effect: word gets around and venues become wary of hosting anything Palestine-related — at a time when it could not be more relevant or topical.

This in turn reinforces the general atmosphere of exceptionalism — that where Israel/Palestine is concerned normal rules do not apply. Criticising Russia’s occupation of Ukraine, for example, is uncontroversial but criticising Israel’s occupation of Palestine is, shall we say, “sensitive”.

UKLFI purports to be acting for the good of society by targeting activities it regards as “divisive” and “inflammatory”, but its complaints don’t necessarily resonate with the public in the way it apparently expects. It expresses horror at use of the words “genocide” and “apartheid” in connection with Israel’s treatment of the Palestinians, but that battle is already lost. Whatever the international courts may eventually decide, talk of “genocide” and “apartheid” is now an established part of mainstream discourse in Britain and elsewhere.

It’s scarcely surprising that UKLFI’s interventions often have the divisive and inflammatory effect it says it is trying to prevent. Its stance as an arbiter of acceptable discourse is seriously undermined by its political support for Israel’s most hardline elements. On the Palestinian issue, UKLFI’s interpretations of the law are wildly out of line with the international consensus and the policies of successive British governments, not to mention rulings by the UN’s highest court. Among other things, UKLFI claims Israel’s occupation of the West Bank is lawful and that Israeli settlements there are legitimate.

In Britain, though, there’s considerably more sympathy for the Palestinians, and more criticism of Israel, than UKLFI seems to imagine or the positions of Britain's political and media establishment would suggest. YouGov polling shows:

- A growing majority (68%) think Israel should stop its military action in Gaza.

- Most people (54%) think the International Criminal Court should issue an arrest warrant for Netanyahu while only 15% oppose it.

- A substantial majority (66%) support a two-state solution with independent Israeli and Palestinian states side by side.

The arts and culture community is one section of society that doesn’t take kindly to outsiders telling it what to do, especially when the underlying message is to keep politics out of art for the sake of Israel. Prominent arts centres become caught up in this, worrying about their reputation, but experience shows that timidity doesn’t pay. Those that give in to UKLFI and its fellow complainers are likely to face an angry response from people in the arts world who guard their right to free expression fiercely with petitions, boycotts, sit-ins and withdrawal from exhibitions.

Voices of Resilience organiser Ra Page argues that many of these problems could be avoided if major venues bothered to read their published policies — and stuck to them:

“Arts organisations spend years developing and signing off policy statements and action plans around equality, diversity and inclusivity, but when they become scared about what they can and can’t say — as in the current situation — they don’t refer to those documents and invoke them to protect Palestinian voices.

“When push comes to shove, people either look down, at their own moral compass, or they look up, at the weather vane, to see which way the wind is blowing. In many cases, they just look up at the weather vane. Perhaps this is why so many of them spoke about Black Lives Matter and the invasion of Ukraine, draped their buildings in the Ukrainian flag, but kept quiet about the genocide in Gaza.”

Barbican (or can't)

The Barbican arts centre in London prides itself on offering “a varied and daring events programme — one which inspires, connects and provokes debate”. A policy statement on its website says:

“Artists play a crucial role in reflecting, commenting on and responding to the issues of the day, including subjects that are urgent, complex or divisive. Cultural institutions such as the Barbican have a responsibility to provide artists — particularly those who may have been marginalised — with a platform to do so.

“Our programming therefore often deals with political and social topics, and we aim to host the broadest and most diverse range of artists and thinkers, representing the widest possible range of world views and human experiences.”

In recent months, though, a couple of incidents at the Barbican have called that commitment into question. In June last year Elias Anastas of the Palestine-based Radio Alhara was due to be interviewed remotely about the subversive possibilities of broadcasting. It was part of a three-day programme at the Barbican by Resolve, “an interdisciplinary design collective that combines architecture, engineering, technology and art to address social challenges”.

The Guardian reported:

“During the soundcheck for the event, Anastas said he received a text message from someone who works at the Barbican saying: ‘In terms of content, avoid talking about free Palestine at length … just to further safeguard the audience.’

“Moments earlier, a member of the Barbican team running the event reportedly pulled aside Anastas’ interviewer, Nihal El Aasar, and asked if she and Anastas could “steer clear of thorny issues” such as “free Palestine … or whatever”. The event was then cancelled due to technical difficulties, understood to be poor wifi.”

The Barbican duly apologised, describing this intervention as “unacceptable and a serious error of judgement, for which we are deeply sorry … We have since spoken and apologised to those involved, and agreed for the talk to be rescheduled in the near future.”

Early this year, the Barbican was planning to host a series of lectures organised by the London Review of Books (LRB), though it had not yet reached a formal agreement. The Barbican suddenly pulled out when the LRB announced that the title of the first lecture, to be given by Indian writer Pankaj Mishra, was “The Shoah after Gaza”.

The explanation given by the Barbican was that it would not have enough time before the event to “do the careful preparation needed for this sensitive content … We carefully consider the content of all screenings, performances, talks and exhibitions hosted by the Barbican before agreeing to host them.”

Shortly after cancelling Mishra’s lecture the Barbican opened a large exhibition — “Unravel: The Power and Politics of Textiles in Art” — which was due to last three months. Several artists and collectors withdrew their exhibits in protest at the Mishra decision. The artworks were replaced by statements explaining their absence.

Pro-Palestine demonstators later occupied the Barbican’s foyer and staged an impromptu “festival” celebrating Palestinian culture. One protester told the Artnet website:

“The Barbican has been heavily complicit but they are not alone. Throughout the culture sector, our institutions have remained silent while using their power to silence the voices of those speaking out against the genocide that is taking place

“The occupation of the Barbican and the reclamation of British cultural space was an important moment to mourn the lives taken by Israel, collectively speak out against the silencing of Palestinian artists, and celebrate Palestinian culture … It was a statement that we will stand together and speak out against the censorship of Palestinian voices.”

That, along with the earlier furore in Manchester, was the background to the Voices of Resilience performance scheduled for last Saturday night. UKLFI had already sent a letter calling for it to be cancelled, with the usual threats of legal repercussions and a complaint to the Charity Commission if it went ahead. However, in the wake of the Mishra affair the Barbican had formally acknowledged that “Gaza is one of the most urgent issues of our time and it is essential we enable critical voices to be heard”.

The question, therefore, was whether the Barbican would stand firm or cave in to UKLFI’s demands. As organiser of the event, Ra Page saw it not only as an opportunity for the Barbican to redeem itself but also as a test case: if the Barbican could host Voices of Resilience, other venues could be more confident about hosting similar events.

UKLFI had claimed the Barbican performance would create an “intimidating, hostile and offensive environment” for any Jews and Israelis attending, and in an apparent move to address those fears the Barbican went to some lengths with its safeguarding.

A few hours before the event ticket-holders received a message warning that there would be “descriptions of violence and references to war, death and displacement”. It advised recipients that a “Quiet Room” and a “Multi Faith and Meditation” room were available “for anyone who would like to take a moment of reflection during the performance” and staff would be on hand to assist.

The message also directed recipients to the Barbican’s “resources” web page listing organisations that provide mental health support and to its Zero Tolerance Policy: “We’re a place of safety and respect for everyone who works here, uses our venue, or visits to enjoy our experiences.”

Unlike the first Voices of Resilience performance in Manchester, security at the Barbican on Saturday was relatively relaxed, without barriers around the entrance. Bags were given a cursory inspection but items showing support for the Palestinians were not banned as they have been at several other venues. Many in the 200-plus audience wore keffiyehs draped over their shoulders.

The performance itself was harrowing. While the course of events in the Gaza war is familiar from news reports, nothing compares with hearing them described by the people on the receiving end. The readings from their diaries told of daily efforts to survive and stay in touch with their families when death can come at any moment — in a word, they spoke of resilience.

The comfortable seats of the theatre were a far cry from the horrors of Gaza but the Barbican, in a different way, was showing resilience too by standing up to UKLFI’s bullying. The audience gave it a round of applause for allowing the event to go ahead, and in the hope that other venues will be encouraged to follow its example.

* * *

More articles about UKLFI

From warfare to lawfare: Israel’s other battleground

2 August 2024

Pro-Israel lawyers target London arts venue in move to silence Palestinian voices

31 August 2024

Prominent Jewish peer resigns from pro-Israel activist group

10 September 2024

Cultural genocide: the battle to suppress Palestinian voices

17 September 2024

Pro-Israel campaigners get references to genocide removed from art exhibition

19 September 2024

Harassment claim by pro-Israel lawfare group ‘wholly without merit’

5 December 2024

Pro-Israel lawyers target climate activists over Gaza

10 January 2025

Shush! Don't mention genocide!

1 February 2025

UKLFI complains that talk of genocide is distressing for Israel’s supporters

21 August 2025

RSS Feed

RSS Feed