Following Saddam Hussein's invasion of Kuwait in 1990, British prime minister Margaret Thatcher advocated using banned chemical weapons against Iraqi forces, declassified documents show. Despite the 1925 Geneva Protocol prohibiting their use, Thatcher repeatedly pressed the US to be ready to retaliate with chemical weapons if Iraq used them first.

Her discussions with the Americans during the Kuwait crisis are described by university professor Nigel Ashton in his recent book, False Prophets: British Leaders' Fateful Fascination with the Middle East from Suez to Syria. Ashton's account is based on the notes of meetings written at the time by Thatcher's private secretary, Charles Powell – notes that Ashton cites as evidence of Thatcher's "gung-ho attitude".

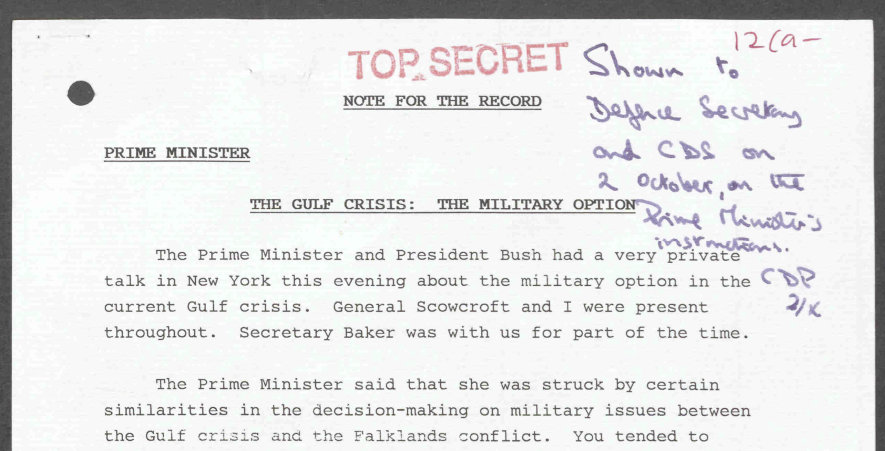

The documents, previously classified as "Top Secret", can now be found in the online archives of the Margaret Thatcher Foundation.

On 30 September 1990 – two months after the Iraqi invasion – Thatcher met President George HW Bush in Washington for what Powell described as "a very private chat". Apart from Bush, Thatcher and Powell, the only others present were Bush's National Security Adviser, Brent Scrowcroft, and for part of the time, Secretary of State James Baker.

Powell wrote a six-page account of the discussion which focused on military preparations for what later became known as Operation Desert Storm.

The meeting began with Thatcher drawing parallels with the 1982 Falklands war and haranguing the president about a need for swift action against Saddam. The window for action was relatively small, she told him – probably between November and March/April when temperatures in the Gulf were "suitable for military operations".

"We had to squeeze into that period both time for sanctions to work and time for a resort to the military option if they did not," Powell's note says. "If the window was missed, we would probably have to wait until next autumn for another chance: and in practice that probably meant never."

|

Thatcher also told Bush it would be a mistake to seek UN backing for military action over Kuwait: there was aleady enough justification and "the UN would only try to put constraints on it."

"Much of this clearly struck the president as new," Powell wrote. At that point Bush had no particular date in mind for military action and his advisers had not mentioned a problem over the weather. He was also unsure at the time about seeking a UN resolution (though he later decided in favour).

In the course of this discussion Thatcher raised the question of what to do if Iraq used chemical or biological weapons.

Bush told her "world opinion would eat Saddam Hussein for lunch" if he resorted to that – to which Thatcher replied that she doubted Saddam would be deterred by world opinion.

She then asked whether the US had any chemical weapons of its own in the area to act as a deterrent, but Bush ejected the idea outright.

According to Powell's note, he told her "use or threatened use of chemical weapons would only put the US in the wrong with world opinion. It would be better to launch an all-out conventional attack and wipe Saddam Hussain off the face of the earth. He was not twenty feet tall."

Meeting with Cheney

Thatcher pressed the point again when she met defense secretary Dick Cheney a couple of weeks later and told him she was "very worried" about Iraq's chemical and biological weapons capability. The Americans, however, were less concerned and some of their intelligence suggested Iraqi weapons of that kind were not particularly effective.

Cheney was one of the most hawkish members of the US administration and Ashton comments the book that on this occasion he "must have been surprised to find himself significantly out-hawked by Thatcher".

The prime minister told Cheney she believed Saddam would use chemical weapons, and "if we wished to deter a chemical attack by threatening to retaliate in like manner, we must have chemical weapons available." Above all, she said, it was vital to work out in advance exactly how to respond to the use of such weapons by Iraq.

Cheney replied that no final decision had been taken on how to respond but cautioned her that the president had "a particular aversion" to chemical weapons. The US military commanders were not keen on them either, because American forces had no experience of using them and many of the weapons themselves were outmoded. Their inclination, therefore, was to rely on massive conventional response to a chemical attack. They were confident that they could eliminate most of Iraq's chemical weapons capability during the initial air strikes.

Nuclear weapons

There had also been reports in the British press, attributed to anonymous "defence sources", hinting at possible use of nuclear weapons in a conflict with Saddam. This had come to Bush's attention and at the September meeting he appeared to chide Thatcher, saying he did not think such stories "were at all helpful".

Nuclear weapons came up again at the October meeting when Cheney asked Thatcher if she could contemplate their use in a Gulf conflict.

According to Powell's notes, Thatcher replied that she would be "most reluctant to consider this, indeed she would rule it out, although nuclear weapons were always there as the ultimate deterrent". Powell's account continues:

"Her main concern was to deter the Iraqis from using chemical weapons, since it would have a very demoralising effect on our forces and on their families. Personally, she believed it would be justified for the United States to use chemical weapons against Iraqi armoured formations in Kuwait if the Iraqis themselves used it first.

"Secretary Cheney repeated that the Americans were relatively less concerned about the chemical threat to their forces in Saudi Arabia. The Iraqis had no experience of using chemical weapons strategically, only as a tactical battlefield weapon. The American military were confident of their ability to prevent Iraqi attempts to use air-delivered chemical weapons against them. The key was to pre-empt their use."

The story of Thatcher and her chemical weapons hawkery forms a small part of Ashton's book which examines how a succession of British prime ministers have become involved in the Middle East – even after the 1956 Suez crisis supposedly put an end to Britain's ambitions in the region. British prime ministers have tended to be false prophets, he says, conjuring existential threats to the western way of life out of the sands of the Middle East.

The book makes extensive use of previously classified documents, some of which the British authorities were extremely reluctant to release. Ashton, who is professor of international history at the London School of Economics, fought a five-year battle to obtain documents covering Britain’s relations with Libya and only succeeded in getting access to them after taking the case to court.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed