At the height of the AIDS epidemic millions of people, especially in the world’s poorest countries, faced illness and death without access to proper treatment — and desperation opened the door for charlatans raising false hopes with quack cures.

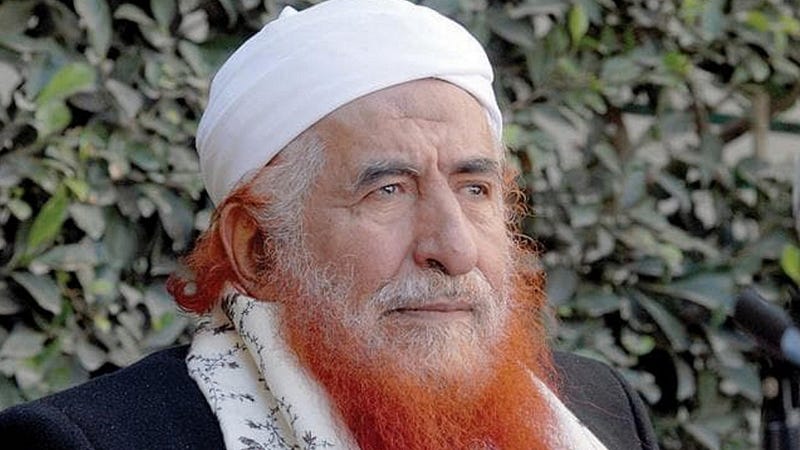

Among them was Abd al-Majeed al-Zindani, one of Yemen’s most controversial religious figures. Zindani was a long-standing friend of Osama bin Laden and had been sanctioned by the UN and US for providing support to al-Qaeda.

He was also the founder and director of al-Iman University in Yemen — an extraordinary seat of learning in more ways than one. Opened in 1993, it attracted Muslim students from far and wide and became a breeding ground for jihadists. Among its alumni were John Walker Lindh, known as the “American Taliban”, and Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the so-called “underpants bomber”. Some of its students were also arrested in Yemen for the murders of three Christian missionaries and a leftist politician.

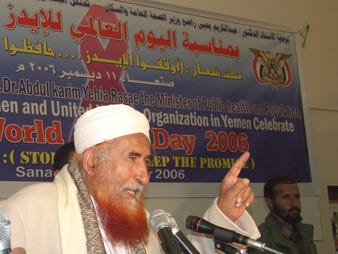

The other notable feature of al-Iman University was its claim to have developed an “Islamic cure” for HIV/AIDS. In 2006 Zindani — a distinctive figure who dyed his grey beard a bright orange-red — turned up uninvited at a World AIDS Day event in the Yemeni capital, Sana’a. Interrupting a government minister’s speech, he told the gathering his university had discovered the long-sought cure.

|

|

Zindani wasn’t the first (or last) to make such a claim. Around the same time, Yahya Jammeh, dictator in the tiny West African state of the Gambia, devised his own “miracle” cure for HIV. He set up a clinic at his presidential residence and pressurised thousands of HIV-positive Gambians into receiving his “treatment”. Patients who had allegedly been cured were paraded on state-run TV. Jammeh’s Presidential Alternative Treatment Programme (PAPT) ran for almost ten years, during which time the number of Gambians known to be living with HIV more than doubled.

There were plenty of others around the world offering dubious cures — often at rip-off prices. One “medication” marketed in Uganda and Kenya costing $1,650 per dose was found to comprise honey and olive oil. Another, developed by an unnamed “herbal specialist in Benin”, is still advertised on the internet at $150 for a two-month supply and its web page contains testimonials from people claiming to have tested HIV-negative after taking the mixture. Scroll down to the bottom of the page and there’s a cautionary note from the seller saying success cannot be guaranteed: “In case of dissatisfaction we undertake to reimburse our customers or to provide them with free products until recovery.”

Zindani, though, was not one of the rip-off merchants — he had grander objectives. It might seem odd that someone so involved with terrorism was so interested in curing HIV but he saw both as a way of advancing Islam.

He was an advocate of “prophetic medicine” (al-tibb al-nabawi) based on folk remedies mentioned in the hadith, a collection of sayings and deeds attributed to the Prophet Muhammad. Substances recommended by the Prophet for treating various ailments included camel’s milk, henna, honey, truffles and “black seeds” (probably the seeds of Nigella sativa).

Zindani was not only seeking to prove the viability of “prophetic medicine” but also to demonstrate its superiority by highlighting what he saw as the failures of conventional medicine — and discovering a “prophetic” cure for HIV would be one way of doing that.

Biomedical science currently regards HIV as controllable but not curable. The standard treatment is anti-retroviral therapy (ART) which suppresses the virus but doesn’t eliminate HIV entirely. If treatment stops the virus becomes active again, eventually resulting in AIDS. No less importantly, when ART is taken as prescribed it reduces the amount of virus in an infected person’s body to undetectable levels, thus preventing transmission to anyone else.

Yemen is one of the world’s poorest countries, its medical facilities are far from adequate and wealthy Yemenis, if they have a serious illness, usually seek treatment elsewhere. Nevertheless, for a brief period Yemen became a centre for medical tourism as reports of Zindani’s discovery sent people with HIV — predominantly Muslims — flocking from neighbouring countries in desperate hope of a cure. Some returned home believing they were no longer infected, having been told by Zindani they could have “normal” sex with their wife.

Before turning his attention to HIV, Zindani had spent years in Saudi Arabia promoting “Qur’anic science” — an idea that Islam’s holy book alludes to various scientific facts which were unknown to humans during the lifetime of the Prophet. The supposed references are cryptic and often ambiguous but Zindani cited them as evidence that this apparent foreknowledge could only have come from God.

Zindani had promoted these claims while working at King Abdulaziz University in Saudi Arabia during the 1980s and in 1984 he obtained Saudi funding for a “Commission on Scientific Signs in the Qur’an and Sunnah”. His tactic was to approach visiting western scientists, present them with verses from the Qur’an and encourage them to say that the verses contained scientific knowledge.

When presented with verses that give a figurative account of the development of the human embryo, one of these scientists — Keith Moore, a Canadian professor of anatomy — concluded that each of the stages described in the Qur’an could be linked to the stages recognised by modern embryologists.

Moore was the author of a respected textbook on embryology and his encounter in Saudi Arabia led to the publication of a new edition with “Islamic additions” written by Zindani. The new version also had an acknowledgements section thanking ten “distinguished scholars” who had given “personal and official” support to the book project. Sixth on the list was “Sheikh” Osama bin Laden.

Zindani’s interest in “Qur’anic science” eventually turned towards “prophetic medicine”. Following his return to Yemen, he established a Centre for Prophetic Medicine at al-Iman University, offering herbal treatment for illnesses that included diabetes, hepatitis and cancer. He also became convinced that a cure for HIV was waiting to be discovered somewhere in the hadith. The Prophet, after all, had assured his followers that God created a cure for every illness except old age.

Zindani claimed that out of more than 25 HIV cases treated with his “prophetic” medicine 13 were completely cured and that its effectiveness had been verified by specialists at King Abdul Aziz University (his former employer) and laboratories in the United States which he did not identify. He refused to disclose the contents of his medication on the grounds that he wanted to keep it secret until a patent had been granted. He also took steps to ensure no one could analyse the medication independently: it was administered at his university and patients were not allowed to take it home with them.

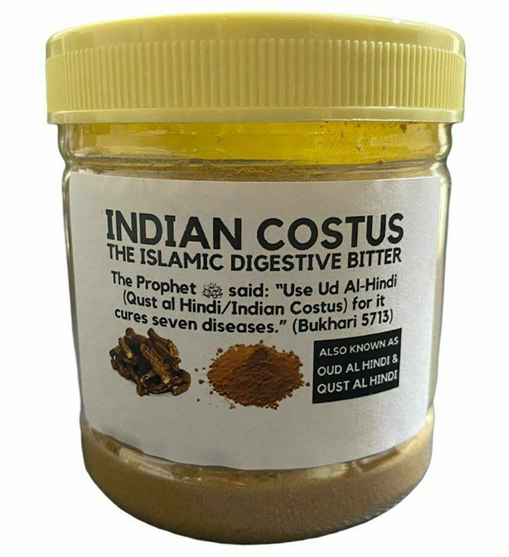

He never succeeded in getting a patent, though he had applied for one through an agent in South Africa. When the application documents became available for public viewing in 2012 Zindani’s secret was revealed. One of its two ingredients was water; the other was a plant called Aucklandia costus and the manufacturing process involved boiling it for “about an hour”. The leaves, stems and flowers could all be used but chopped-up roots were better, the documents said.

Aucklandia costus is a thistle-like plant native to the Himalayan regions of India and China. It has been used in various parts of the world for centuries — mostly for medicinal purposes but also sometimes as a spice. It is known by several other names including Dolomiaea and Saussurea, and colloquially as costus in English or qust in Arabic. Many Muslims equate it with “al-’ud al-hindi” — a substance described by the Prophet in a hadith as curing seven different illnesses. Costus is widely available on the internet, marketed for its alleged health benefits, including enhancement of men’s sexual performance.

|

In Yemen, Zindani’s intervention was distinctly unhelpful for the science-based National AIDS Programme. His religious status made local health professionals wary of challenging his claims directly, fearful that they would be accused of questioning Islam. A visiting researcher from Georgetown University noted that while almost all of them stressed that there was no proof of Zindani’s cure and generally discouraged people from receiving his treatment they were reluctant to say explicitly that it didn’t work. One interviewee quoted criticisms made by a Saudi doctor rather than saying what his own opinion was.

There were some suggestions that Zindani’s religious connections encouraged more people with HIV to come forward. In Yemen HIV had been widely regarded as a disease that “good” Muslims did not catch and it could be argued that his willingness to treat it with “prophetic medicine” helped to offset some of the moral stigma: people who sought treatment at al-Iman could be viewed as devout rather than deviant.

However, one of the attractions of al-Iman was that people could receive “treatment” there while keeping their HIV status secret. Some turned to al-Iman because they were suspicious of the government’s National AIDS Programme — fearing that if their HIV status became known to the authorities it might not remain confidential. At al-Iman, on the other hand, they didn’t necessarily need to disclose their status: many were ostensibly seeking treatment for hepatitis C rather than HIV. It didn’t make much difference because Zindani’s Aucklandia costus remedy was used for a variety of illnesses (with larger doses in the case of cancer patients).

Some of Zindani’s patients did switch to anti-retroviral treatment later, after coming into contact with a local HIV support group and joining the National AIDS Programme. Meanwhile, those who didn’t switch were left with false hopes and a false belief that they were no longer at risk of infecting anyone else.

Al-Iman university remained open in Sana’a until 2014 when Houthi rebels who had seized control in northern Yemen shut it down because of religious and political differences with Zindani.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed