A group of university professors who promoted conspiracy theories about chemical weapons in Syria are now making similar claims about the recent chemical attack in Britain which critically injured Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter.

The "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" was set up in January, comprising professors and other academics from universities in Britain, the US, Sweden and New Zealand.

It purports to be engaged in "rigorous academic analysis" of media reporting of the Syrian conflict and the role played by propaganda, but on closer examination the group itself seems more like a propaganda exercise than a serious academic project.

Previously published articles by members of the group cast doubt on their claims of "rigorous academic analysis". They dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation. Several of the group also make frequent appearances on the Russian propaganda channels, RT and Sputnik.

Last week the group published its first "working paper" and, rather oddly, it was not about Syria but about Britain and Russia.

The paper, co-authored by Professor Paul McKeigue of Edinburgh University and Professor Piers Robinson of Sheffield University, claims the British government has developed a way of producing the "novichok" compound that poisoned the Skripals.

Related blog posts

9/11 truther joins Syria 'propaganda research' group

19 March2018

'Propaganda' professors switch focus from Syria to Britain and Russia

18 March2018

Russia-friendly 'Syria propaganda' group names more supporters

6 March2018

The Syrian conflict's anti-propaganda propagandists

24 February 2018

Since the first confirmed use of a nerve agent in Syria in 2013, defenders of the Assad regime – and especially the Russian government – have been claiming it was a "false flag" attack by rebels, intended to discredit the regime.

Following the nerve agent attack in Britain earlier this month, similar "false flag" claims have been circulating on the internet, suggesting the British government carried it out in order to stir up public opinion against Russia. Russian propaganda channels have been eagerly promoting that idea too.

In their working paper, Paul McKeigue and Robinson point to a possible British source for the nerve agent. "Porton Down [the British research establishment] must have been able to synthesize these compounds in order to develop tests for them," they say (italics added).

Their claim, though, is simply wrong. Being able to test for a particular compound does not require an ability to produce it.

The working paper is also at pains to question whether Russia could have produced a "military grade" version of the nerve agent, though the relevance of that is unclear. There would be no need to have developed it for battlefield purposes in order to use it against two individuals in Salisbury.

Prof Robinson, who teaches journalism studies at Sheffield, had a busy time last week. He also appeared on both RT and Sputnik talking about the Skripal affair. In addition, his group's working paper about novichoks was featured in an article on Sputnik's website where he was described as an academic "with knowledge of chemical weapons".

Robinson's co-author, Paul McKeigue, is Professor of Genetic Epidemiology and Statistical Genetics at Edinburgh. In a previous publication, McKeigue deployed Bayes’ theorem and probability theory to claim there is "overwhelming" evidence that rebels in Syria used the nerve agent sarin at Ghouta in 2013 and Khan Sheikhoun in 2017. He managed to reach that conclusion even though the sarin used on both occasions was of a type made by the Syrian government and there is no credible evidence that the rebels ever possessed sarin.

Another prominent member of the "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" is Tim Hayward, Professor of Environmental Political Theory at Edinburgh University, who re-posted the article by Robinson and McKeigue on his personal website.

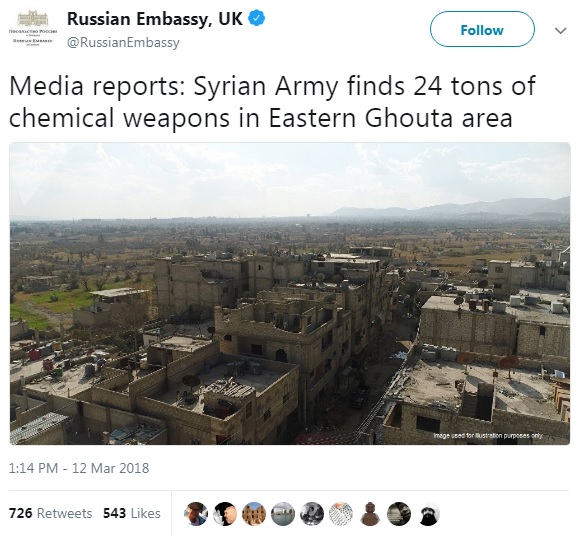

On Monday he re-tweeted a statement from the Russian embassy in London claiming that the Syrian army had found "24 tons of chemical weapons" in an area of Ghouta previously held by rebels.

Hayward commented: "You can see why the British elite do not want us getting any news via Russia" and it was indeed easy to see why – because the Russian claim was demonstrably false.

Various chemicals had been found at what was described as a rebel laboratory but there was no evidence of chemical weapons. Even RT's reporter on the spot, Sharmine Narwani (see previous blog posts here, here, and here) was struggling.

"Is this a chemical weapons lab?" she asked, "Or simply a chemical lab manufacturing a substance used in warfare – like explosives? Even if no banned chemical munitions are found to be produced at this lab, its discovery is a game-changer ..."

Similar stories of "chemical" discoveries have been reported by propagandists in the past with the aim of connecting the rebels to nerve agent attacks. In 2013, for example, RT broadcast clips from Syrian state TV showing poisonous materials allegedly found in a rebel "laboratory". The only identifiable substance in the video was a series of bags labelled as caustic soda produced in Saudi Arabia.

Images of other supposedly sinister rebel-held equipment included medical supplies from a Qatari-German company.

Above: a previous Russian video about a rebel "laboratory" in Syria and (below) medical supplies seized from rebels.

The internet, of course, is awash with spurious claims and fanciful theories but it's disturbing to see university professors joining in and reinforcing that nonsense under the guise of "rigorous academic analysis".

The British government is partly to blame. It has allowed wild speculation to flourish by not being more forthcoming with information about the Skripal attack.

Conspiracy theories tend to be far more interesting than the truth – which is part of their appeal. They also give believers a sense of superiority: by refusing to even consider that mainstream narratives might be correct they can claim not to be fooled by propaganda. But in the process they actually fall straight into the propagandists' trap.

The best defence against being fooled is to look at whatever evidence is available, consider it in the round and apply basic common sense.

Writing for the website politics.co.uk last week, Ian Dunt said:

"Strip it down to its bare bones and you've got a relatively simple situation here. The evidence overwhelmingly points to Russian state involvement. They have the motivation, they have the ability and they have the track record. No-one else does.

"But it is not proven yet and in all likelihood, because of the nature of the operation, never will be. So there is enough doubt for conspiracy theories to blossom and nervy politicians to be frozen by inaction.

"At other times, the obvious story would have defeated the imaginative ones. But we are not living in normal times."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed