here." src="/sites/default/files/ru-cyl-4.jpg" style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; height:322px; width:550px" />

A recent report by the chemical weapons watchdog, OPCW, has caused a flurry of activity among defenders of the Assad regime who claim chemical attacks in Syria have been faked or staged by rebels.

The obvious conclusion to be drawn from the OPCW report was that two cylinders of chlorine gas had been dropped from the air on the town of Douma last April – in which case it’s clear they were dropped by pro-Assad forces, since the rebels had no aircraft.

Undaunted by that, Syria “truthers” turned their attention to a third cylinder which was also mentioned in the report. Although OPCW investigators found no evidence linking it to chemical weapons, the regime’s defenders claim otherwise and have turned its discovery into a propaganda weapon.

While the truthers’ insistence that this third cylinder was part of a “false flag” plot by rebels to discredit the regime bears little scrutiny it’s a prime example of the way snippets of information can be manipulated to cast doubt on mainstream explanations of events in Syria.

Unidentified chemicals

Once chemical weapons became an issue in the conflict the Assad regime and its allies began publicising various discoveries of “chemicals” and “laboratories” in rebel hands. The main purpose of reporting these discoveries was to suggest that rebel forces were manufacturing chemical weapons for use in “false flag” attacks.

Last year, for example, Vanessa Beeley, a prominent defender of the regime, visited what she claimed – without evidence – was a rebel “chemical weapons facility” captured by government forces.

In her report for the conspiracy-theory website 21st Century Wire, she described seeing numerous sacks and containers but her military escorts said some of them were booby-trapped, so she couldn’t examine them closely. The only “chemical” she clearly identified was RDX, a common type of explosive, though her article included a series of photos showing unidentified substances that it claimed were “chemical weapon ingredients”.

A Russian ‘discovery’

On 17 April – ten days after the Douma attacks and three days after the US, Britain and France launched reprisal strikes against the regime – Russia announced that its troops had made a new discovery in the Douma area. TASS news agency described it as “a militants’ lab for the production of chemical weapons and the storage of its components”, while Sputnik News talked of “a warehouse of substances necessary for the production of chemical weapons”. Videos circulated by Russian media showed various items in the basement of a war-damaged apartment block, including a large yellow cylinder possibly containing chlorine gas.

At Syria’s request, the OPCW agreed to visit the site and concluded that the Russian claim was false. While it found chemicals “consistent with the production of explosives and propellants” there was no sign of “any major key precursors” for chemical weapon production.

However that didn’t explain the yellow cylinder which, according to Russia and Syria, contained chlorine. Its contents have not been confirmed by the OPCW whose investigators decided it would be too hazardous to tamper with the cylinder’s valve in order to obtain a sample. Nevertheless, it’s likely that the cylinder did contain chlorine (or had done so in the past). Gas cylinders are normally colour-coded and, although coding systems vary, yellow commonly indicates chlorine.

The question this raises is why a cylinder of chlorine gas – if that’s what it was – would be stored in a makeshift explosives factory because, as the OPCW noted, it was not relevant to manufacturing explosives. Equally, though, the investigators found no evidence of an intention to use it as a chemical weapon. Chlorine is a common substance with multiple civilian uses, including the purification of water.

When a chemical becomes a weapon

Under the Chemical Weapons Convention, any toxic chemical can potentially become a chemical weapon. The test is whether it has been “specifically designed to cause death or other harm” through its toxic properties.

Unlike the cylinder seen in the rebel explosives factory, the two cylinders implicated in the Douma attacks had been specially adapted for use as weapons. They had been fitted inside a metal frame to provide wheels, lugs for lifting, and tail fins.

The addition of fins is especially significant because, according to a previous OPCW report, it shows the adapted cylinders were meant to be dropped from a height, with the fins stabilising their descent. The same OPCW report also said it was reasonable to conclude that cylinders adapted in this way were chemical weapons since they were “not designed to cause mechanical injury through explosive force”.

On that basis, the “rebel” cylinder can’t be considered as a chemical weapon because, in the words of the OPCW investigators, it was “in its original state and had not been altered”. The investigators also noted “differences” in this cylinder compared with the two implicated in the Douma attacks, but gave no details.

Twitter activity

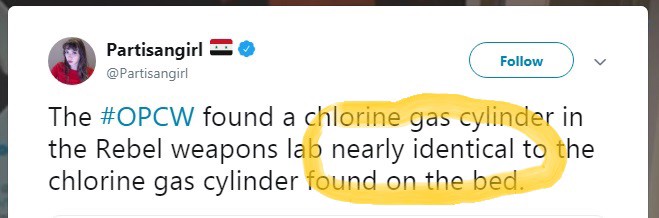

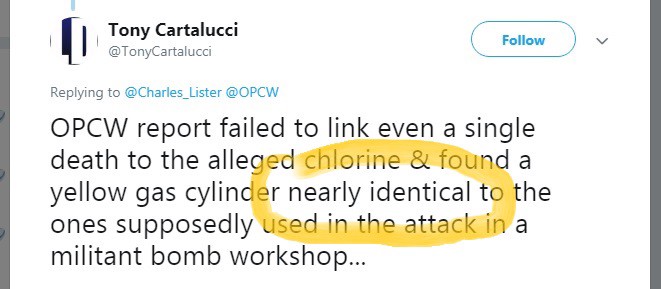

Inconvenient as this was for the regime’s defenders, they were not to be put off by the investigators’ findings. Despite the OPCW’s mention of differences, in postings on Twitter the “rebel” cylinder became “nearly identical” to the other two:

… and …

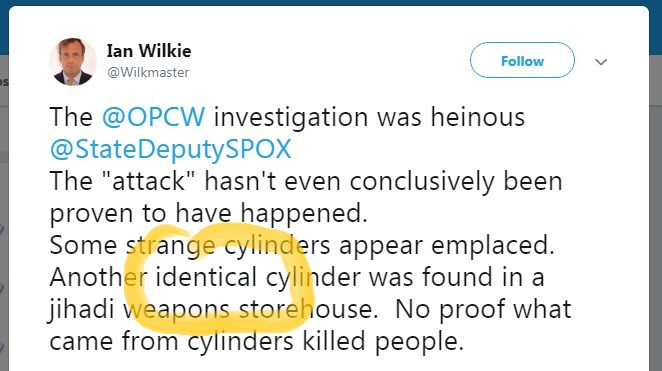

Another Twitter user, Ian Wilkie, who has a history of spreading false information about Syria (see here and here), even dispensed with the word “nearly”:

The three who posted these tweets – Partisangirl, Tony Cartalucci and Wilkie – are all regular promoters of “alternative” narratives about Syria, and by presenting the third cylinder as “identical” or “nearly identical” to the other two they were implying a connection that could not be justified by the evidence.

The key difference was that the third cylinder had not been adapted for use as a weapon. For what it’s worth, the third cylinder was also of a different type. Unlike the two weaponised cylinders, it had a second outlet sealed with a metal nut adjacent to the main valve.

This can be seen as a small protrusion in the OPCW’s photo of the cylinder though it’s partly obscured behind the main valve. There are other photos on Twitter that show it more clearly.

There was no such outlet on the two weaponised cylinders, as can be seen from other photos in the OPCW report:

Meanwhile, in an article for 21st Century Wire, Cartalucci acknowledged that the “rebel” cylinder had not been adapted like the other two but wrote:

“The obvious implications of a nearly identical canister turning up in a militant workshop making weapons is that the militants may likely have also made the two converted canisters found at locations 2 and 4 [where the chemical attacks are reported to have occurred].”

In the absence of any evidence that rebels were making the metal frames that turned ordinary gas cylinders into chemical weapons it’s difficult to see how Cartalucci could reach that conclusion, but he continued:

“The presence of a canister nearly identical to those found at locations 2 and 4 in a militant weapons workshop provides at least as much evidence that militants staged the supposed chemical attack as the Western media claims the canisters at locations 2 and 4 suggest it was the Syrian government.” [Italics added.]

This is a ridiculous claim but it’s par for the course. While the truthers are ultra-sceptical about evidence from western sources and international bodies such as the UN and OPCW, they seem happy to trust the Assad regime and its allies.

Thus, in his article for 21st Century Wire, Cartalucci dismisses the OPCW report on Douma as “too ambiguous to draw a conclusion” and, in an article for Global Research (another conspiracy-theory website) he complains that some munition fragments passed to the OPCW for testing “lacked a chain of custody, negating its probative value”.

Oddly, though, he shows no interest in questioning the “rebel” cylinder’s chain of custody. How can we be sure that the cylinder was in the basement store when rebels abandoned it and was not placed there later after the Russian troops arrived?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed