The Saudi-led coalition waging war on Yemen's Houthis is undergoing emergency repairs following last week's armed clashes between rival anti-Houthi forces.

The whole of Shabwa province is now said to be under the control of government forces after a failed attempt by southern separatists – trained and supported by the UAE – to drive them out.

Meanwhile on Saturday, the Saudis and the Emiratis sought to patch up their differences with a joint statement affirming their desire "to preserve the Yemeni nation and the interests, security, stability, independence and territorial integrity of the Yemeni people under the leadership of the legitimate president".

On 10 August separatist forces linked to the Southern Transitional Council seized control of Aden on the grounds that the internationally-recognised government of President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi was failing to provide adequate protection. For several days they appeared to be making relatively easy gains elsewhere in the south until meeting fierce resistance in Ataq, in Shabwa province.

The southern issue in Yemen

More background on the conflict between separatists and the "legitimate" government

Ataq is the gateway to an oil-producing region further north which is claimed by the separatists but held by government forces. Following a battle in and around Ataq on Thursday night, separatist forces throughout Shabwa appear to have capitulated rapidly, forfeiting their earlier gains in the province.

However, the local separatist forces, known as the Shabwani Elite, have not necessarily withdrawn. There are indications that at least some of them have simply been re-branded as government forces under commanders pledging allegiance to Hadi.

There's little doubt that the separatists had over-stretched themselves in Shabwa but it appears that their actions were also a step too far for their Emirati backers who were accused by the Yemeni army of supporting "outlawed groups".

Messy situation

Even if Shabwa goes quiet, this still leaves a very messy situation on the ground in Yemen's south and attempts to resolve it could easily make matters worse.

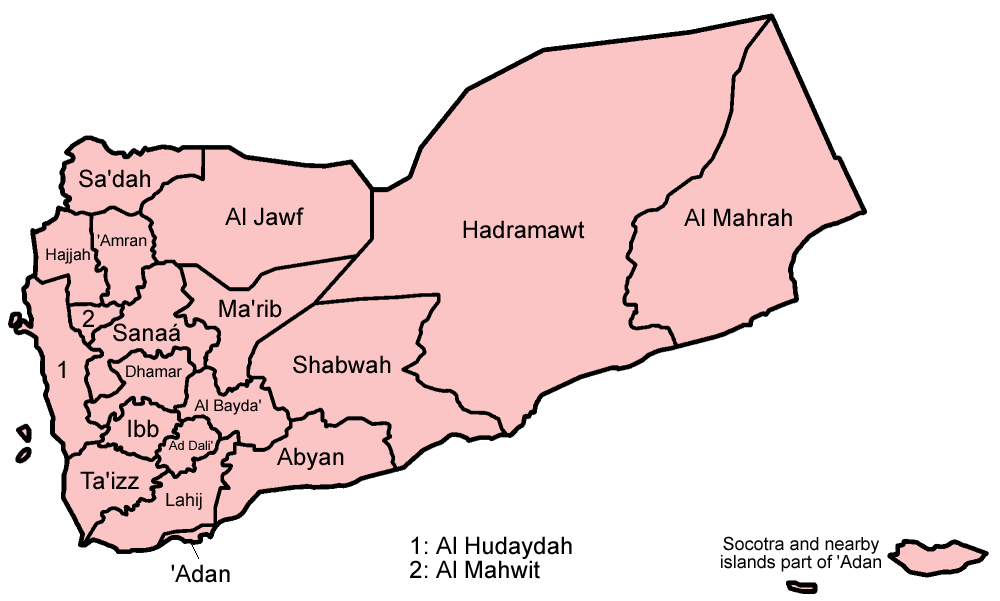

Government control over Shabwa isolates the two eastern-most provinces in the south – Hadramaut and al-Mahra – from the western provinces around Aden where the separatists dominate. This raises the possibility of further fragmentation. There are some elements in Hadramaut and al-Mahra who want their own mini-state – and with a small population and significant oil resources they would probably benefit economically by going their own way.

It remains to be seen whether the Southern Transitional Council will be allowed to retain its current grip on security in the south's western provinces. If not, separatist sentiment there is likely to be further inflamed. Allowing it to continue, though, could be a step on the road towards a formal secession.

A major problem on the other side is Hadi's feeble government, which the UN and the coalition are committed to supporting. What legitimacy it had when the war began has mostly evaporated and the only good reason for supporting it now is fear of the alternatives.

Hadi's vice-president, appointed in 2016, is Ali Muhsin al-Ahmar – an army general whose forces hold both of the main oil-producing areas. While Ali Abdullah Saleh was president, Ali Muhsin had a terrifying reputation and Saleh used to fend off critics by saying that if he stepped down his successor was likely to be Ali Muhsin.

Ali Muhsin's connections with Islamists are a particular concern of the separatists and the Emiratis, though the Saudis appear less troubled by them.

In a leaked memo written in 2005, Thomas Krajeski, the US ambassador in Yemen at the time, wrote:

"He is known to have Salafi leanings and to support a more radical Islamic political agenda than Saleh. He has powerful Wahhabi supporters in Saudi Arabia and has reportedly aided the [Saudis] in establishing Wahhabi institutions in northern Yemen. He is also believed to have been behind the formation of the [Islamist] Aden-Abyan army, and is a close associate of noted arms dealer Faris Manna."

The memo also described Ali Muhsin as "a major beneficiary" of oil smuggling – though he denied it.

After four years of war, the Saudis are now saying that the only way for Yemenis to overcome internal differences is through dialogue – though they seem to be referring to the south specifically, rather than the whole country. But dialogue is unlikely to be enough. There needs to be fresh thinking about a political way forward – and not just about the south.

The complexity of Yemen's problems and the need for a change of focus is well illustrated by veteran Yemen watcher Helen Lackner in an article published yesterday. She concludes by saying:

"The UN and its Special Envoy are, not for the first time, out of sync with the situation. Having ignored other issues and focused almost exclusively on Hodeida and the humanitarian situation for two years, it is now faced with a situation where Hodeida is no longer the main crisis in Yemen. Response to the humanitarian crisis is affected by low funding (mostly because Saudi Arabia and the UAE are not fulfilling their pledges) but is also facing serious ethical issues with diversion of funds and aid, including by UN agency staff.

"Rather than transferring focus to the latest outbreak in the south, UN politicians would be wiser to take a broader approach and develop a medium to long-term strategy addressing the overall Yemeni crisis."

RSS Feed

RSS Feed