|

There are a few countries in the world where the coronavirus pandemic has not followed the course that scientists expected – and the reasons are puzzling.

Yemen is one example in the Middle East and there are others in Africa such as Kenya, Tanzania, Sudan and Somalia.

Covid-19 took a long time to reach Yemen but when it took hold it struck with a vengeance. In the southern city of Aden, May and early June was a desperate time: hospitals were overwhelmed and gravediggers could scarcely keep pace with the burials. Ammar Derwish, a doctor in the city, kept a diary where he described people "falling down, one by one, like dominoes". It would begin with a fever, quickly followed by difficulty in breathing, and then sudden death.

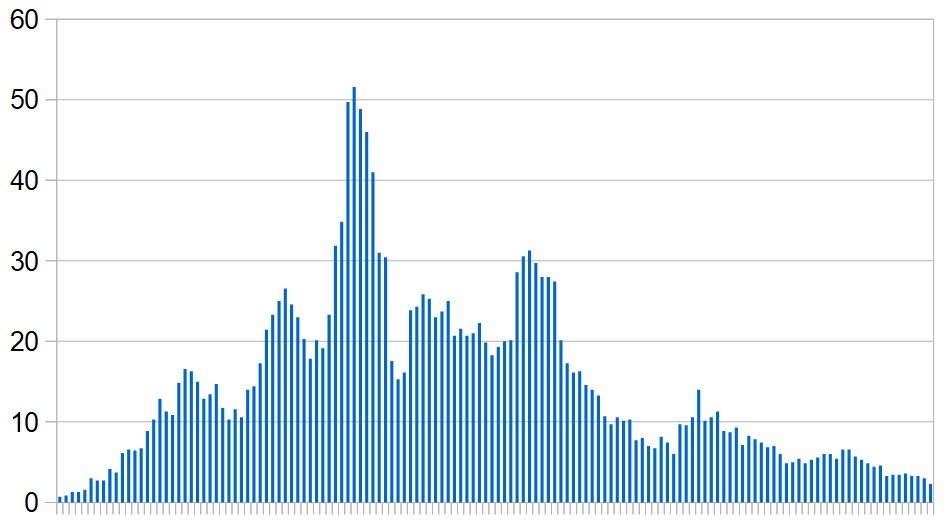

Litttle was done to prevent infections spreading and official figures show the epidemic rose to a peak in mid-June. But then something changed. According to Dr Derwish, new cases quickly dropped to a trickle – and, for what it's worth, the official figures support that view.

A note of caution is needed here. It's difficult to get tested for Covid-19 in Yemen and because of social stigma attached to the disease there are also many people who don't want to be tested. Health services are in a terrible state and even where medical help is available people are often wary of seeking it.

But while there have almost certainly been a lot more cases in Yemen than the 2,000 shown by official figures, fluctuations in the official figures – up or down – give a general guide to the course of the epidemic. This is supplemented by evidence from unofficial sources.

|

“The anecdotal reports we’re getting inside Yemen are pretty consistent that the epidemic has, quote unquote, passed,” Professsor Francesco Checchi, an epidemiologist at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, told British MPs recently. “There was a peak in May, June, across Yemen, where hospitalisation facilities were being overwhelmed. That is no longer the case.”

Why this has happened is still a mystery since – as the professor told MPs – Yemen is one of the few countries where there is almost no effort to prevent Covid-19 transmission.

Five years of armed conflict have left many Yemenis under-nourished and, in theory, more susceptible to infection. Diseases that are rare in better-off countries, such as cholera, diphtheria, dengue fever and chikungunya are prevalent in Yemen.

That – counter-intuitively – could be part of the explanation for Covid-19's retreat there. One possibility suggested by Prof Checchi is that previous exposure to other diseases has given Yemenis some protection against the coronavirus.

So far it's only a hypothesis, but an intriguing one nevertheless.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed