A few years ago Egypt's Supreme Council for Media Regulation decreed that gay people must not appear in print or audio or visual media "except in recognition and acknowledgment of their misconduct". In other words, if they are to be seen or heard at all, gay people should always be presented in a negative light.

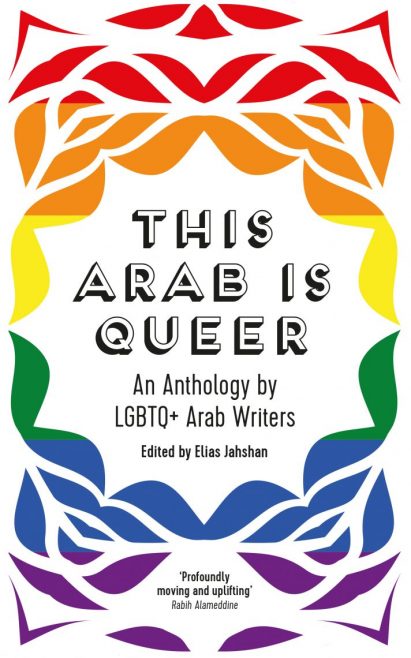

One antidote to that comes in the form of a new book unashamedly titled 'This Arab is Queer' – though it probably won't be on sale in Egypt any time soon. It's a collection of personal stories and reflections by 18 Arabs who identify as somewhere on the LGBTQ+ spectrum.

Besides challenging popular stereotypes, these accounts build into a more positive picture than might be expected: they show that some queer Arabs, at least, manage to integrate their sexuality or gender identity into everyday life.

Even so, much of that takes place against a background of social and religious disapproval. Ahmed Umar recalls his first same-sex kiss during a school lunch break in Saudi Arabia, and the mental turmoil that followed: "I had never felt so good. I had never felt so bad," he writes. "I waited for Allah’s revenge. Would the earth split and swallow me, like the people of Lot in Sodom and Gomorrah? Or would I be punished with eternal unhappiness? Maybe I was already infected with AIDS."

|

Several writers describe how they came out to their family or – worse – were found out. The reactions range from rejection to acceptance but there are also occasional surprises.

Anbara Salam had been dropping hints about her sexuality and keying herself up for the expected conversation with her parents but it never materialised. Her parents clearly didn't want to talk about it and simply ignored the hints. For many Arabs, that would have come as a relief, because when acceptance is impossible, silence is better than rejection.

"These withheld conversations serve us," Salam writes, "by providing shields that, in many places, literally save lives from legal and social censure. They invite convenient amnesia, avert judicious eyes, swallow tuts at the back of the throat." But, as she notes, silence also creates a barrier. "The cost of that barrier is to accept that those closest to you do not really know you, and that feels especially alienating when the love-language of your culture is intrusion. It means leaving unshared all the messy, low-level melodrama of relationships, friendship fallouts, disappointments, celebrations, milestones, anniversaries."

Meanwhile, Madian al-Jazerah experienced another kind of denial that was almost comical. He hadn't been planning to come out but, in his late thirties, his sexuality put his life in danger and he needed to explain to his family why he was leaving Jordan. His mother had only one question. "Are you this?" she asked, cupping her hand, "Or are you this?" – poking a finger with the other hand. "If you are the poker, it’s OK, you are not a homosexual ... you can get married and have children."

'An act of moral terrorism'

The Egyptian ban on positive coverage of gay people resulted from what one horrified religious leader described as "an act of moral terrorism". It happened in 2017 during a music festival in Cairo when Mashrou' Leila, a popular but controversial Lebanese band, performed for a crowd of 35,000. One of their songs is about same-sex love and their lead singer, Hamed Sinno (another of the book's contributors), is openly gay. Several members of the audience showed their appreciation by waving rainbow flags.

In the ensuing uproar over this flag-waving the Egyptian authorities launched a crackdown. The Syndicate of Musical Professions – a government-linked body tasked with suppressing "abnormal" kinds of music in Egypt – added Mashrou' Leila to its banned list and the Egyptian authorities rounded up dozens of people suspected of being gay. One of those detained – a young lesbian named Sarah Hegazi – later took her own life.

The rainbow flags affair resurfaces in a chapter by "Amina", the book's only contributor writing under a pseudonym, who describes her night of joy at the now-notorious Mashrou' Leila concert: Hamed sings "about us and for us", the crowd goes wild at the sight of the flags and two young men who don't know any different kiss. It feels almost like Pride, she writes – "not across oceans and borders among strangers ... but here, in Cairo".

By next day, though, the mood has changed. As the flag-wavers are reviled on national TV, Amina's mother asks if they are talking about the concert she went to last night ... "I clutch my mug, the roll of my eyes a well-rehearsed lifebuoy that I hope will buy me enough time before I have to respond." She writes: "Our community knows few things as well as we know 24-hour-long panic attacks, when the air shifts and the state starts hunting and the men delete the apps and we brace ourselves. We are learning, slowly, how to hold each other through them."

Amina's story ends with reflections on her brother's wedding party: "I recognise the look he gives his bride, because I have looked at a woman the same way ... I have known that love, joyous and overflowing."

But she also knows her own relationships are of a kind that cannot be celebrated so openly. "My mother will never be happy for me like she is tonight for my brother. She will not invite her friends to see as she beams at her life coming full circle, or run to the DJ requesting songs I can twirl her to on the dance floor. My mother, to whom I have lied about so many of my sadnesses, will not find it in her to dance with me on that day, and I will not ask her to."

Life as an outsider

Sexuality and gender identity are not necessarily the only factors that make LGBTQ+ Arabs "different" or outsiders – and there are reminders of that from several of the book's contributors. "From a young age, I was off the social beat," Ahmed Umar recalls:

"I was known for being the only Sudanese boy in the whole school. Not only that, but a Sudanese who was not very dark skinned ... I was often asked questions like: ‘How can you be Sudanese when you’re not charcoal-black?’ On many occasions I had my headwear taken off by the other boys so that they could mess up my exposed afro. I was also called a girl, by both students and teachers. While deep within me I never took it as an insult, I still had to act as if I did, to avoid raising suspicions."

Amna Ali, from a Somali family living in the Emirates, faced bullying and racism as the only black student in a school of 700 girls: "I was a minority within a minority within a minority. A black, queer Arab and apostate child of very religious immigrant parents." She writes:

"I developed an inferiority complex and internalised everything I was told about being queer and black: my gross, ugly hair, my home-cooked food smelling bad, and the weird other language (Somali) I spoke at home. And, at home, I wasn’t taught pride and to stand up for myself; I was always told to keep my head down and stay out of trouble.

"These days, I wish I could tell my 16-year-old self that things get better, just as it got better for me. I came out and cut the homophobic members of my family off, I left Dubai and moved to Toronto. I put me and my needs first and I am now proudly and outspokenly (almost obnoxiously so) out of the closet. I no longer fear my family’s reaction when they find out. I no longer live in a country with homophobic laws."

Trophy hunters and white saviours

There's another way that race can enter the equation, though it's not often discussed and mainly affects Arabs in the diaspora. Saeed Kayyani recalls feeling disconcerted by some of the attention from admirers while living in the US: "Apparently, my ethnicity in itself was attracting men. This was a feature of being a gay Arab that I hadn’t anticipated."

One cisgender white Republican man urged Kayyani not to worry about it: "Dude, openly gay Arabs like you are so rare. You’re like forbidden fruit ... Take it as a compliment." In the book, Kayyani treats it as mildly amusing but also troubling: "It was almost as if I wasn’t being regarded as an individual ... Would it have made any difference if I had been substituted with some other Arab guy?"

In a chapter titled "Dating white people", Tania Safi tells of a similar experience with a lover in Australia who endlessly complimented her on her "dark-haired, tan-skinned" appearance and told her "I love that you are Lebanese, speak to me in Arabic".

"Naïve as I was," Safi writes, "something didn’t feel right. I wasn’t aware of the concept of racialised fetishisation, but I knew how it felt."

Alongside these trophy hunters there are also what Kayyani, an Emirati, describes as "white saviours". One of them sent him this message on Facebook:

"Sweetheart, I understand that being gay is hard in general anywhere in the world, but I just wanted to let you know that I’m here for you. As someone with a degree in International Relations, I know that gayness is especially hard over there and will make others want to kill you in Arabia. You can always talk to me, all right? It would help since I also have a certificate in psychological counselling."

Kayyani comments:

"After a cold shower to process what exactly I had just read, I had a few immediate reactions. First, why was she assuming I was in danger? Yes, my country’s LGBTQIA+ situation was a massive don’t-ask-don’t-tell cosplay scenario, but I was in no danger. Every queer community across the globe has unique struggles and challenges specific to its location – but with modernisation, education and social media, physical danger is simply not a contemporary and immediate concern for us in the Gulf."

Saying it in English

Elias Jahshan, the book's Palestinian-Lebanese-Australian editor, says he was looking for contributors who could write interestingly and in English, though he adds: "I am deeply conscious of the fact it won't be accessible to everyone in the Arab world simply because English (or French) is a language of the educated."

English also tends to be the favoured language for discourse about Arab LGBT+ issues – at least, the more thoughtful sort. Since 2016, at least ten novels or memoirs by or about queer Arabs have been published in English:

Saleem Haddad: Guapa (2016)

Danny Ramadan: The Clothesline Swing (2017)

Leila Marshy: The Philistine (2018)

Amrou Al-Kadhi: Life as a Unicorn (2019)

Zeyn Joukhadar: The Thirty Names of Night (2020)

Zeina Arafat: You Exist Too Much (2021)

Randa Jarrar: Love Is an Ex-Country (2021)

Madian Al Jazerah: Are You This? Or Are You This? (2021)

Omar Sakr: Son of Sin (2022)

Fatima Daas: The Last One (2022)

For those Arabs who view homosexuality as a foreign phenomenon and others who claim LGBT+ activism is a form of cultural imperialism, this might be seen as confirmation of their views but the reality is that it's largely a result of conditions in the Middle East: restricting the discourse drives it abroad. Writing about sexual orientation or gender identity in Arabic and publishing in the Middle East is far more problematic than writing in English and publishing in the west.

A struggle to be heard

Large-scale crackdowns, as seen in Egypt over the rainbow flags, attract media attention but they only happen occasionally. In the meantime, though, there's the constant drip-drip of smaller-scale attempts to prevent LGBT+ voices in the region from being heard.

In one of the book's chapters Khalid Abdel-Hadi describes the harassment he faced in Jordan publishing My Kali, an online LGBT+ magazine in both English and Arabic. Surprisingly, though, My Kali has survived for 15 years.

Even in Lebanon, where activism dates back to the early 2000s, a concert scheduled for the recent LGBT+ week had to be cancelled because of threats and, following complaints from religious elements, the interior ministry denounced similar LGBT+ events as a violation of "our society’s customs and traditions".

Last month, under pressure from authorities in the UAE, Amazon began blocking LGBT-related items on the Emirati version of its website (amazon.ae). If you search for "gay" or "LGBT", for example, the website reports "no results" and advises: "Try checking your spelling".

The filtering system is crude and erratic, though. Of the ten novels and memoirs mentioned above, five are listed, two are completely absent and two are listed as "currently unavailable" with no details beyond their cover and title. Rather oddly, Fatima Daas's book is on sale through Amazon's Emirati website in French, Italian, Spanish, Catalan and German translations, but not in English.

Weirder still, although you won't find 'This Arab is Queer' on the Emirati site, if you search for it Amazon helpfully suggests three LGBT-related alternatives – Saleem Haddad's 'Guapa' (“only 1 left in stock, more on the way”), Randa Jarrar's 'Love is an Ex-Country' ("10% discount with Citibank") and a novel by the gay Lebanese-American writer Rabih Alameddine. The purpose of such absurdity, Amazon says, is to comply with local Emirati laws against homosexuality.

Obstacles of this kind are a persistent feature of the ongoing struggle, making it easy to overlook progress in the opposite direction. That's where 'This Arab is Queer' comes in: its overall tenor is cautiously hopeful and perhaps the most remarkable thing is that it exists at all. Ten to fifteen years ago the chances of finding 18 Arab contributors who identify as LGBT+, all but one of them willing to write under their real name, would have been slim or non-existent. This in itself suggests some kind of shift is taking place, if so far mainly on the margins.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed