Syria accuses US and UK of supplying chemical weapons to rebels

Blog post, 17 August 2017: At a news conference in Damascus yesterday, Syria's deputy foreign minister accused the US and Britain of supplying rebel fighters with chemical weapons. The claim has excited Russian media – especially Sputnik News which has published multiple stories on the topic.

Sputnik wonders if this could be a "turning point" in the war and a step towards "exonerating" the Assad regime over chemical weapons attacks. It quotes Kevin Barrett of the Muslim-Jewish-Christian Alliance for 9/11 Truth as saying:

"History will show that it actually has been elements of the so-called Syrian rebels and their foreign backers, including the US, that have been guilty of introducing chemical weapons into this conflict."

Meanwhile, TASS news agency quotes Russian foreign ministry spokeswoman Maria Zakharova as saying:

"The fact is that the western states and regional countries have directly or indirectly supplied banned poisonous substances to militants, terrorists and extremists active in Syria."

According to the Syrian government, quantities of the riot control chemicals CS and CN gas were found in Aleppo province and East Ghouta near Damascus, in stockpiles abandoned by rebels. Markings are said to have identified the manufacturers as NonLethal Technologies in the US and Chemring Defence in Britain.

The gas counts as a banned chemical weapon when used in warfare though, rather oddly, it is legal when used for dispersing riots by civilians.

If the gas did fall into rebel hands, it's unclear how it got there. There is no evidence so far that either of the companies knowingly supplied the rebels or that they did so as part of a policy by the American or British governments.

CS gas manufactured by Chemring was used by the Mubarak regime during the 2011 uprising in Egypt but the company said that either the gas was old stock, since it had stopped supplying Egypt in 1998, or had been obtained by Egypt via a third country.

A joint UN/OPCW team is currently working to identify "perpetrators who use chemicals as weapons" in Syria, and hopes to report back in October. Although use of tear gas by rebels would not be excusable, the most serious part of the investigation relates to use of the nerve agent sarin, which has killed hundreds during the conflict.

Several recent reports indicate continued use of chemical weapons since the Khan Sheikhoun sarin attack in April which resulted in the American bombing of Shayrat air base. The chemical mostly used in these latest attacks is thought to have been chlorine.

Earlier this week the Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) blamed the regime for at least five chemical attacks that have taken place since April:

"Most of those attacks involved the use of hand grenades that were loaded with a gas believed to chlorine in the context of military progress on battlefronts of which the Syrian regime seeks to take control from armed opposition factions."

The SNHR supported its claim with statements from witnesses.

Last month, citing western intelligence sources, the German news organisation, Welt, said the regime had used chemical weapons in Damascus on multiple occasions, including twice in Ghouta on July 11 and 14, and 4 times in Ain Tarma, on July 1, 6, 13 and 14. Two days before the article was published another attack was alleged on July 20, again in Ain Tarma.

The report is in German but has been summarised on the Bellingcat website where there are also videos of people said to have been injured in the attacks.

Chemical weapons in Syria: what is the Assad regime hiding?

Blog post, 6 September 2017: In 2012, as armed conflict raged in Syria, the Assad regime gave assurances it would never use chemical weapons against its own people, "no matter what the internal developments in this crisis are".

Speaking at a news conference, foreign ministry spokesman Jihad Makdissi insisted the country's chemical weapons were intended only for national defence and there was also no chance of them falling into the wrong hands: "All varieties of these weapons are stored and secured by the Syrian armed forces and under its direct supervision, and will not be used unless Syria is subjected to external aggression."

At the time, Syria – along with Egypt, North Korea and South Sudan – was one of only four countries that had not signed the Chemical Weapons Convention, the international pact banning possession and use of such weapons, and was widely believed to have been secretly developing them – mainly in response to Israel's nuclear programme. Makdissi's statement, though, was the first official confirmation that Syria did in fact possess chemical weapons.

Since the spring of 2013 numerous chemical attacks have been documented in Syria. The regime denies any responsibility for them and, at first sight, seems eager to identify the culprits. However, its attitude towards international investigations tells a different story – one which is scarcely suggestive of innocence.

Renouncing chemical weapons

In August 2013, hundreds of people died when rebel-held areas of Ghouta, on the outskirts of Damascus, were attacked with the nerve agent, sarin. This was the most serious chemical attack in Syria to occur so far and it caused an international outcry. Suspicion fell on the regime and, under the threat of US military action, it agreed to join the Chemical Weapons Convention.

By joining the convention, Syria committed itself to chemical disarmament. It was required to declare all its stocks and related production facilities, which would then be destroyed or dismantled under supervision of the international Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW).

The start looked promising. Syria wasted no time in submitting its declaration and, in a speech to the OPCW's executive committee, assistant foreign minister Husamuddin Alla boasted that it had done so four days ahead of the legal deadline. This, he said, was a sign of Syria's "full commitment" to complying with its obligations under the convention.

It wasn't long, however, before the OPCW's assessment team began finding errors and omissions in the Syrian declaration. Some of them might be attributed to initial confusion about what information was required under the complicated rules of the convention but, almost four years later, despite numerous amendments to the original declaration, the OPCW has still not accepted it as complete. There remain "gaps, inconsistencies and discrepancies" (to use the OPCW's phrase) which have yet to be explained.

While it might be expected that the number of unresolved issues would have been whittled down over time, in Syria's case the opposite happened. According to the OPCW, the number has "steadily increased" – along with the assessors' scepticism.

In a blistering report last year, the OPCW's director-general, Ahmet Üzümcü, complained that many of Syria's answers to questions were "not scientifically or technically plausible". In many instances, he said, new information proffered by Syria "presents a considerable change in narrative from information provided previously – or raises new questions. In some cases, this new information contradicts earlier narratives."

Gaps in the regime's declaration

Full details of Syria's declaration have not been made public but documents on the OPCW's website show the regime disclosed 41 chemical facilities at 23 sites:

- Eighteen chemical weapons production facilities, including some for filling weapons

- Twelve chemical weapons storage facilities, consisting of seven reinforced aircraft hangars and five underground structures

- Eight mobile units for filling weapons

- Three other facilities related to chemical weapons

As far as actual weapons were concerned, the regime declared:

- 1,000 tonnes of Category 1 chemicals

- Approximately 290 tonnes of Category 2 chemicals

- Approximately 1,230 unfilled chemical munitions

- Two cylinders, later found to contain sarin, which the Syrian authorities said did not belong to them

(Category 1 means "high risk" chemicals, including nerve agents, which are considered especially hazardous and which have little or no use outside chemical warfare. Category 2 includes "significant risk" chemicals such as phosgene which also have some legitimate civilian uses.)

Despite Syria's claim of making "all possible efforts" to fulfil its obligations, there is now no doubt the declaration was incomplete – though how incomplete remains an unanswered question.

Syria had initially declared four different chemical warfare agents but, following "consultations" with the OPCW, it added a fifth to the list. Later, tests on samples obtained by inspectors in Syria "indicated potentially declarable activities involving five additional chemical agents". More "consultations" ensued and the list grew to six. The most recent information from the OPCW is that there are still four chemical agents detected through sampling whose presence the regime "has not yet adequately explained".

Discrepancies and difficulties

There were also discrepancies between Syria's records of chemical weapons production and the quantities it had declared. The OPCW said it was "unable to verify the precise quantity of chemical weapons that were destroyed or consumed" before Syria signed up to the convention. At one point Syria claimed it had used 15 tonnes of nerve agent and 70 tonnes of sulfur mustard for research – figures that the inspectors found hard to believe since only tiny amounts would be needed for research.

On the munitions front, there were difficulties accounting for 2,000 or more chemical shells which Syria said it had either used or destroyed – after purportedly adapting them for non-chemical purposes. Again, the inspectors doubted the truth of this because converting the shells into conventional weapons would scarcely have been justified by the effort and expense.

In August 2014 the OPCW certified that all the Category 1 chemicals declared by Syria (primarily nerve agents and their precursors) had been destroyed. That, of course, did not resolve the question of whether Syria still had undeclared stocks or production facilities – a question that became especially pertinent following the sarin attack in April this year that killed dozens of people in Khan Sheikhoun.

Aside from questions about the declaration, inspectors working on the ground in Syria faced various difficulties which might – to put a charitable spin on them – be attributed to the foibles of Syrian bureaucracy but which cumulatively gave the impression of intentionally hampering investigations.

According to a report by Anthony Deutsch of Reuters, these have included "withholding visas, submitting large volumes of documents multiple times to bog down the process" and last-minute restrictions on site inspections. Deutsch describes one example of these restrictions in 2015 that aroused inspectors' suspicions:

A Syrian major general escorted a small team of chemical weapons inspectors to a warehouse outside the Syrian capital Damascus. The international experts wanted to examine the site, but were kept waiting outside in their car for around an hour, according to several people briefed on the visit.

When they were finally let into the building, it was empty. They found no trace of banned chemicals.

"Look, there is nothing to see," said the general, known to the inspectors as Sharif, opening the door.

So why were the inspectors kept waiting? The Syrians said they were getting the necessary approval to let them in, but the inspectors had a different theory. They believed the Syrians were stalling while the place was cleaned out. It made no sense to the team that special approval was needed for them to enter an empty building.

Deutsch's report also hints at obstruction during some of the interviews conducted by inspectors:

In Damascus, witnesses with knowledge of the chemical weapons programme were instructed by Syrian military officials to alter their statements midway through interviews with inspectors, three sources with direct knowledge of the matter told Reuters.

There are indications, too, that inspectors have not been allowed to interview the most relevant people. In his 2016 report, Üzümcü urged the authorities in Damascus to "facilitate access to individuals with strategic knowledge and oversight" of the chemical weapons programme.

A new twist: chlorine bombs

While struggling to verify Syria's declaration, the OPCW has also been working separately through its fact-finding missions to investigate reported chemical attacks in Syria, and a UN-OPCW panel known as the Joint Investigative Mechanism has been assigned the task of identifying perpetrators.

Internationally, it is the deadly nerve agent sarin that has caused the most alarm but sarin is not the only chemical at issue. Chlorine has been used “systematically and repeatedly” according to the OPCW and sulfur mustard – commonly known as mustard gas – has been used to a lesser extent too. At least one of the mustard attacks, at Um Housh a year ago, was blamed by locals on ISIS.

Chlorine is a common substance with multiple civilian uses but is classed as a chemical weapon when used in warfare. Although less toxic than sarin, it irritates the eyes and skin, and can cause permanent lung damage. In high concentrations it can be lethal.

The regime appears to have begun chlorine attacks in 2014, just a few months after officially renouncing chemical weapons. Numerous witnesses have described chlorine bombs being dropped from helicopters – in which case rebel groups could not be responsible since they have no aircraft.

Furthermore, the OPCW was able to confirm the air-dropping of chlorine bombs. From photographed remnants of the bombs it established that they were designed as free-fall weapons, with stabilising fins so that the detonator section would hit the ground first. There was no sign of a propulsion system and they were judged too large to be launched from land-based artillery systems.

Thus the regime's use of chlorine is beyond reasonable doubt – which puts it in breach of the Chemical Weapons Convention. But chlorine doesn't arouse the same kind of international horror as sarin and the OPCW has pursued the issue less vigorously. One reason is that chlorine bombs came into use at a time when dismantling Syria's declared chemical stockpile was seen as the top priority and there were fears that a new confrontation over chlorine could jeopardise that process.

Click to enlarge. Source: OPCW." src="/sites/default/files/chlorine-bomb.jpg" style="border-style:solid; border-width:1px; height:302px; width:450px" />

Feeding scepticism

If, as the regime claims, it was not responsible for any of the chemical attacks and has been honest in its declaration to the OPCW, it has not tried very hard to demonstrate its innocence. In a way, though, it doesn't need to. It is protected by Russia in the UN Security Council and where chemical weapons are concerned the American appetite for unilateral military action appears to be limited. Trump's response to the sarin attack in Khan Sheikhoun last April – firing dozens of cruise missiles at Shayrat airbase, the alleged source of the attack – was certainly dramatic but of dubious effectiveness. The missiles cost US taxpayers around $49m but the cost to the regime was relatively insignificant and the base was reportedly operational again very swiftly. If anything, the bombing of Shayrat may have encouraged the regime to step up its use of chlorine.

In the propaganda war, the regime also benefits from the Iraq effect. Regardless of how much evidence the OPCW produces, significant sections of the public – some of them very active on social media – remain sceptical. Although the regime is known to have possessed sarin and there is no credible evidence that rebel groups ever had access to it, the deception by western governments in 2003 over Saddam Hussein's non-existent weapons of mass destruction still makes people wary.

The regime has exploited this with a media strategy which is aimed at feeding people's doubts rather than putting forward a coherent narrative in its defence. The basic technique – in which Russia has also been very active – is to promote "alternative" theories, often plucked from unreliable sources on the internet, and then accuse the UN/OPCW of failing to investigate them seriously.

It doesn't much matter if the "alternative" theories conflict with each other and are not supported by credible evidence, so long as they can be kept in circulation. The point is not really to convince anyone that they are true but to neutralise public opinion. If multiple theories can be kept floating around in the mix, the idea that the regime attacked its citizens with sarin starts to look like one possible explanation among many and, with luck, people will be unsure which of them – if any – to believe.

Claims of faked videos

In 2013, two days after the Ghouta attacks, Russian foreign ministry spokesman Aleksandr Lukashevich asserted that YouTube videos of victims posted on the internet were fakes. The idea had come from a pro-Hizbullah website which wrongly claimed that the videos in question (along with a Reuters report of the attack) had appeared the day before the attack took place.

The apparent discrepancy in timing was a result of different time zones around the world – YouTube videos are automatically stamped with the local time in California which is 10 hours earlier than Damascus time – but that did not put paid to the claims about faked videos. Shortly afterwards, Mother Agnes, a Syrian-based nun in the Melkite Catholic church who was sympathetic towards the regime, issued a report disputing 13 of the videos.

"The civilian population in East Ghouta as presented in those videos is inconsistent with the composition of a real civilian society", she wrote. "There is a flagrant lack of real civilian families in East Ghouta, as presented by the videos."

Mother Agnes claimed that some of the children seen in the videos were not from Ghouta but had been kidnapped by jihadists earlier in the summer from pro-regime villages in other parts of the country.

Three of the videos, she said, showed "artificial scenic treatment using the corpses of dead children", while in others she suggested the children were anaesthetised or merely sleeping. Human Rights Watch dismissed Mother Agnes's claims as baseless but the Russian propaganda channel, RT, continued to treat her as a quotable source.

Alleging that images of the victims were faked implied there were no real victims to film, and on that point Assad supporters initially hedged their bets. Lukashevich, for example, talked of an "alleged" attack and a "so-called" attack on Ghouta while citing the supposedly premature videos as evidence of "a pre-planned action" which signalled the launch of "another anti-Syrian propaganda wave". Similarly, Mother Agnes talked of both "a forged story and a false flag".

The idea that the Ghouta attacks might have been invented by rebels became difficult to sustain amid growing evidence of real sarin use, however. Denying that it was the regime's sarin meant blaming the rebels instead – which in turn required some explanation as to why they would have massacred their own people.

Here again, the false flag theory came into play but another suggestion that excited Russian officials for a while was that the deaths had simply been an accident. Little more than a week after the attacks Mint Press, a US-based website, published a story claiming the deaths were a result of rebels mis-handling chemical weapons supplied to them by Saudi Arabia. According to the story, the Saudis had not informed the rebels they were chemical weapons or given instructions on how to use them. The only evidence to support this claim was a series of quotes from unidentifiable people in Damascus.

Accident theories surfaced again in 2017 when Syrian and Russian officials claimed the regime had not intentionally released sarin at Khan Seikhoun but that the Syrian air force had hit rebel-held chemicals during a bombing raid. Syria's foreign minister, Walid Muallem, said the raid had targeted a depot used by Jabhat al-Nusra which contained chemical weapons. Russian defence ministry spokesman Igor Konashenkov elaborated, saying the site included "workshops for manufacturing bombs, stuffed with poisonous substances".

As an explanation for the deaths caused by sarin, this was scientifically implausible. Even if the rebels had access to sarin (and there is no reason to think they did) they are unlikely to have held stocks of sarin as such. It is highly corrosive and degrades quickly in storage, so it is usually stored in binary form – as two separate components which are not mixed until just before use. Also, any actual (ready-mixed) sarin that was hit by a bomb would very probably be destroyed in the explosion. A UN report commented:

"It is extremely unlikely that an air strike would release sarin potentially stored inside such a structure in amounts sufficient to explain the number of casualties recorded. First, if such a depot had been destroyed by an air strike, the explosion would have burnt off most of the agent inside the building or forced it into the rubble where it would have been absorbed, rather than released in significant amounts into the atmosphere. Second, the facility would still be heavily contaminated today, for which there is no evidence."

'Clear and convincing evidence'

Within a month of the Ghouta attacks a report from the UN investigative team headed by Professor Åke Sellström informed the Security Council there was "clear and convincing evidence that surface-to-surface rockets containing the nerve agent sarin" had been used.

At a news conference, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov acknowledged the use of chemical weapons but said Russia still suspected rebel forces were behind it: "We have very serious grounds to believe that this was a provocation."

He added that the investigators' report did not answer a number of questions Russia had asked, including whether the weapons were produced in a factory or home-made. The report, he said, should be examined not in isolation but along with evidence from the internet and other media, including accounts from "nuns at a nearby convent" [i.e. Mother Agnes] and a journalist who had spoken to rebels [i.e. the Mint Press article).

Assad: 'Any rebel can make sarin'

In an interview with Fox News a day after the UN report appeared, President Assad remained ambivalent about the events in Ghouta. Asked if he agreed with the UN's assessment "that a chemical weapon attack occurred on the outskirts of Damascus on August 21", he replied cryptically: "That's the information that we have, but information is different from evidence."

Pressed further, Assad said he was not disagreeing with the UN report but "you have to wait till you have evidence. You can agree or disagree when you have evidence." To Fox News's comment that the UN had already provided the necessary evidence, he responded: "We have to discuss it with them, we have to see the details."

Ignoring the results of laboratory tests, he went on to suggest – as Mother Agnes and the Russians had done earlier – that videos showing victims of the attacks had been faked.

"No-one has verified the credibility of the videos and the pictures ... You cannot build a report on videos if they are not verified, especially since we lived in a world of forgery for the last two years and a half regarding Syria. We have a lot of forgery on the internet."

On the question of who might be responsible for the attacks, Assad then made the startling claim that "any rebel can make sarin".

"Sarin gas is called kitchen gas," he said. "Do you know why? Because anyone can make sarin in his house."

Alternatively, he suggested, rebels could have got sarin from abroad: "We know that all those rebels are supported by governments, so any government that would have such chemical material can hand it over to those."

As far as home-made sarin is concerned, it's not a realistic proposition – especially in the quantities used for the Ghouta attacks – and so far no one has produced any credible evidence of rebels receiving sarin from abroad.

Åke Sellström, the chief UN weapons inspector, was puzzled that Syrian authorities persisted with these theories without producing evidence to support them. Interviewed in 2014, Sellström said:

"Several times I asked the government: can you explain – if this was the opposition – how did they get hold of the chemical weapons?

"They have quite poor theories: they talk about smuggling through Turkey, labs in Iraq and I asked them, pointedly, what about your own stores, have your own stores being stripped of anything, have you dropped a bomb that has been claimed, bombs that can be recovered by the opposition? They denied that.

"To me it is strange. If they really want to blame the opposition they should have a good story as to how they got hold of the munitions, and they didn’t take the chance to deliver that story.

Strange as that might have seemed to Sellström, it was perhaps only to be expected. Clarity is what the investigators seek but for the regime obfuscation can be a lot more useful.

Seymour Hersh wins award for discredited article about Syria

Blog post, 7 September 2017: Seymour Hersh, the American journalist who wrote an error-strewn article about the chemical attack on Khan Sheikhoun in Syria, is this year's winner of an annual prize for truth-telling. He is due to be presented with the Sam Adams Award for Integrity on September 22 during a conference at the American University in Washington.

The citation makes clear that he is being honoured specifically for his article about Khan Sheikhoun which was published by the German news organisation Welt in June and has since been thoroughly discredited.

The citation says:

"This year’s award goes to renowned Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, Seymour Hersh, for his most recent report earlier this year on President Donald Trump’s lie that a Syrian aircraft carried out a 'chemical weapons attack' in Syria’s Idlib Province on April 4."

Hersh's article attempted to explain away dozens of deaths from the nerve agent sarin by suggesting that Syrian forces using a conventional explosive bomb had accidentally hit a store of "fertilisers, disinfectants and other goods" causing "effects similar to those of sarin".

Laboratory tests supervised by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) later confirmed that sarin had indeed been used. Yesterday, a report from a UN Commission of Inquiry concluded that the sarin attack had been carried out by the Syrian air force, and that this consituted a war crime and a violation of the Chemical Weapons Convention.

Hersh's "fertiliser" theory, which was not scientifically feasible, was the most serious error in his thinly-sourced article but there were other problems with it too (see here and here).

Subsequently, Hersh declined to engage in discussion about his article and responded to one journalist's questions by saying that in his long career he had "learned to just write what I know and move on".

Hersh, who won a Pulitzer prize for journalism 47 years ago, has done valuable reporting in the past. He exposed the Mai Lai massacre in Vietnam back in 1969 and, more recently, the horrors of Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Some of his other exposés have misfired, though, and he has often been criticised for his use of shadowy sources. In the words of one Pentagon spokesman, Brian Whitman, he has "a solid and well-earned reputation for making dramatic assertions based on thinly sourced, unverifiable anonymous sources".

Another complaint about his more recent work is that he spends too much time listening to his unidentified sources and not enough looking at open-source evidence which points in a different direction. In an earlier article where Hersh suggested the Assad regime had not been responsible for Sarin attacks near Damascus in 2013, he either overlooked or disregarded evidence which didn't fit his argument and posed a number of questions which other writers had already answered.

His 2013 article was rejected by the New Yorker magazine and eventually published in Britain by the London Review of Books. However, the London Review of Books rejected his most recent article on Syria – which is why it ended up being published in Germany.

Hersh's admirers (of whom there are many on social media) discount the most likely reason for these rejections – that his editors found the articles flaky – in favour of a media conspiracy, and the organisers of the Sam Adams prize seem to have adopted a similar view.

The award citation continues:

"Despite his reputation and the importance of the story, Hersh tried in vain to find a US or British outlet that would publish his report, and eventually ended up having to go to the mainstream German newspaper Die Welt to get the results of his investigation published.

"The common challenge we all face is getting such information into media outlets that US citizens regularly access. Encouragement comes from Hersh’s example of grit, integrity and tenacity, which have already had a powerful influence on Sam Adams Associates. In sum, this year’s awardee is a wonderfully good fit."

Previous winners of the award have included Julian Assange, Edward Snowden and Chelsea Manning.

Syria and sarin: Seymour Hersh pulls out of award ceremony

Blog post, 21 September 2017: A ceremony where American journalist Seymour Hersh was due to be presented with an award for an error-strewn article about a chemical attack in Syria has been cancelled.

Three weeks ago Hersh was named as this year's winner of the Sam Adams Award "for integrity and truth-telling".

The citation stated that Hersh was being honoured specifically for an article published in June by the German news organisation Welt which has since been thoroughly discredited.

In the article, Hersh attempted to explain dozens of deaths from the nerve agent sarin by suggesting that Syrian forces using a conventional explosive bomb had accidentally hit a store of "fertilisers, disinfectants and other goods" causing "effects similar to those of sarin".

Laboratory tests supervised by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) later confirmed that sarin had indeed been used and a report from a UN Commission of Inquiry concluded that the sarin attack had been carried out by the Syrian air force. (See previous blog post for further discussion of Hersh's article.)

Hersh had been due to collect his award at a ceremony on Friday during a "No War 2017" conference at the American University in Washington.

A conference programme issued earlier this month said the presentation ceremony would take place at 8pm on September 22 and added: "Presenting this year will be Elizabeth Murray, Annie Machon, Larry Johnson, Larry Wilkerson, and Philip Giraldi, with special guest Chelsea Manning".

A revised version of the programme has now replaced this with a 15-minute musical interlude, after which Sam Adams Associates (organisers of the award) will present an unspecified "event" with Elizabeth Murray, Annie Machon, Larry Johnson, Larry Wilkerson, Daniel Ellsberg, Thomas Drake, Ray McGovern, and Ann Wright.

A note in the programme says: "Chelsea Manning sends regrets that she cannot attend as we had hoped, as does Seymour Hersh." No reason is given for Hersh's non-attendance.

The inclusion of Larry Wilkerson in the list of participants is interesting because of similarities between an interview given by Wilkerson last April and Hersh's subsequent article for Welt. These suggest that either Wilkerson, a retired US Army colonel, was one of the anonymous sources quoted in Hersh's article or that both Hersh and Wilkerson had been getting inaccurate information from a shared source.

One of the similarities was that both Wilkerson and Hersh made the scientifically impossible claim that the symptoms caused by sarin in Khan Sheikhoun could be the result of an air raid hitting stocks of fertiliser.

The Sam Adams Award was established by Ray McGovern, a former CIA officer turned activist who is also co-founder of VIPS (Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity).

Seymour Hersh accepts 'truth-telling' award, but not for articles on Syria

Blog post, 25 September 2017: American journalist Seymour Hersh – author of several error-strewn articles about chemical attacks in Syria – has accepted a controversial award for "truth-telling" even though the previously-announced presentation ceremony was cancelled.

Hersh received the award at a "festive dinner" on Friday after organisers re-drafted the citation to provide a different reason for giving it to him. The new wording played down his flawed reporting on Syria and instead celebrated him as someone whose yet-to-be-written work might deter Donald Trump from bombing North Korea.

Three weeks ago Hersh was named as this year's winner of the Sam Adams Award "for integrity and truth-telling". The original citation stated specifically that he was being honoured for an article published in June by the German news organisation Welt which has since been thoroughly debunked.

In the article, Hersh attempted to explain dozens of deaths from the nerve agent sarin by suggesting that Syrian forces using a conventional explosive bomb had accidentally hit a store of "fertilisers, disinfectants and other goods" causing "effects similar to those of sarin". This was scientifically impossible and laboratory tests later confirmed that sarin had been used.

Hersh had been due to collect his award – a candle holder for "shining light into dark places" – at a ceremony on Friday during a "No War 2017" conference at the American University in Washington. However, the ceremony was removed from a later version of the conference programme and a note was inserted to say that Hersh would not be attending.

The original award citation was a follows:

"This year’s award goes to renowned Pulitzer prize-winning journalist, Seymour Hersh, for his most recent report earlier this year on President Donald Trump’s lie that a Syrian aircraft carried out a 'chemical weapons attack' in Syria’s Idlib Province on April 4. This disclosure of a deception by the new President would have been a big deal, at least by the journalistic standards of the past, since Trump openly attacked Syria with 59 cruise missiles on April 6 in ostensible 'retaliation'.

"Despite his reputation and the importance of the story, Hersh tried in vain to find a US or British outlet that would publish his report, and eventually ended up having to go to the mainstream German newspaper Die Welt to get the results of his investigation published.

"The common challenge we all face is getting such information into media outlets that US citizens regularly access. Encouragement comes from Hersh’s example of grit, integrity and tenacity, which have already had a powerful influence on Sam Adams Associates. In sum, this year’s awardee is a wonderfully good fit."

The re-drafted citation switched its focus from Syria to North Korea, suggesting that Trump could hold back from bombing Pyongyang – for fear of what Hersh might write about it:

"Sy Hersh, this year’s Sam Adams honoree for integrity, has had the courage to use his unparalleled access to sober-minded senior officials to expose U.S. government misdeeds. This may prove to be a more effective deterrent to President Donald Trump attacking North Korea than the nuclear bombs and missiles at the disposal of North Korean leader Kim Jong-un.

"How can this be true? Because truth tellers in our national security establishment would tell Sy. And even if Sy’s words could appear, at first, only in German, as was the case when Sy exposed Trump’s lie about a Syrian Air Force’s 'chemical weapons attack' in early April, there is a good chance the world would quickly know – this time, hopefully, before a US attack 'in retaliation'.

"It seems likely that Trump would be more hesitant to risk having to sit in the war-crime dock at Nuremberg II, than he would be to risk the carnage that an attack on North Korea would bring to the entire peninsula, and beyond. Such is the potential power of the pen. Sy Hersh’s pen."

The Sam Adams Award was established by Ray McGovern, a former CIA officer turned activist who is also co-founder of VIPS (Veteran Intelligence Professionals for Sanity).

Exonerating Assad: how reports twisted Mattis's comments on sarin in Syria

Blog post, 9 February 2018: At a news conference last week US defence secretary James Mattis was asked about reports of recent chemical attacks in Syria using chlorine.

"Is this something you're seeing that's been weaponised?" a reporter asked.

"It has," Mattis replied, adding that the deadly nerve agent sarin may have been used too: "We are more – even more concerned about the possibility of sarin use, the likelihood of sarin use, and we're looking for the evidence."

Later, asked to clarify his remark about sarin, Mattis said the new reports of its use were unconfirmed but there were grounds for suspicion because of the Assad regime's previous behaviour:

"We think that they did not carry out what they said they would do back when – in the previous administration, when they were caught using it. Obviously they didn't, 'cause they used it again during our administration.

"And that gives us a lot of reason to suspect them. And now we have other reports from the battlefield from people who claim it's been used.

"We do not have evidence of it. But we're not refuting them; we're looking for evidence of it."

Despite the uncertainty about recent claims of sarin use, Mattis was clearly not disputing that the regime had used it for the 2013 attacks in Ghouta which killed hundreds of people (during the Obama administration).

Following those attacks, Syria joined the Chemical Weapons Convention which required it to hand over all stockpiles and production facilities for destruction under OPCW supervision. However, the regime did not fully comply: it either concealed some of its sarin stockpile or secretly produced fresh supplies.

In April last year, shortly after Trump became president, sarin was used again – this time in Khan Sheikhoun. Again, Mattis did not dispute that.

Laboratory tests show the sarin used in both attacks – Ghouta in 2013 and Khan Sheikhoun in 2017 – had chemical "signatures" which link it to the Assad regime's distinctive production process.

Misleading reports

In the week since Mattis's news conference his remarks have generated some extraordinarily misleading reports.

Politico got it more or less right with a headline saying "Mattis warns Syria not to use chemical weapons again". However, a widely-circulated report from Reuters was more confused. It said Mattis "stressed that the United States did not have evidence of sarin gas use" – without making clear that he was talking about recent attacks rather than the earlier ones.

Meanwhile, the Russian propaganda channel, RT, went much further. Its report began:

"Washington has no evidence that the chemical agent sarin has ever been used by the Syrian government, Pentagon chief James Mattis has admitted."

This was completely untrue. Mattis had made no such suggestion.

Now, Newsweek is at it too. An article posted on its website yesterday begins:

"Lost in the hyper-politicized hullabaloo surrounding the Nunes Memorandum and the Steele Dossier was the striking statement by Secretary of Defense James Mattis that the US has 'no evidence' that the Syrian government used the banned nerve agent Sarin against its own people."

Written by Ian Wilkie, who is described as an international lawyer, US Army veteran and former intelligence community contractor, it continues:

"Mattis offered no temporal qualifications, which means that both the 2017 event in Khan Sheikhoun and the 2013 tragedy in Ghouta are unsolved cases in the eyes of the Defense Department and Defense Intelligence Agency."

This is the exact opposite of what Mattis actually said. He raised no doubts at all about the regime's culpability for the Ghouta and Khan Sheikhoun's attacks, as a quick check of the transcript would have shown.

Sarin in Syria: Newsweek is at it again

Blog post, 19 February 2018: What on earth is going on at Newsweek? An article posted on its website earlier this month wrongly claimed that James Mattis, the US defense secretary, had said there is no evidence of the Assad regime using the nerve agent sarin against its people.

The claim attributed to Mattis was demonstrably untrue, as could be seen from the published transcript of his remarks. Despite that, the article remains on Newsweek's website – uncorrected – and continues to be promoted on social media by conspiracy theorists and Assad apologists.

It might be assumed that Newsweek, having got its fingers burned once, would – at the very least – think twice before accepting more articles from the same author. But no. On Saturday there was another one, this time asking: "Where's the evidence Assad used sarin gas on his people?"

The author of both articles was Ian Wilkie, described by Newsweek as "an international lawyer and terrorism expert and a veteran of the US Army (Infantry)". He is said to be is working on a book, "Checkmate: Jihad's Endgame", about the potential uses of weapons of mass destruction by terrorists.

The problem with the first article was that Wilkie drew sweeping conclusions based on what he thought Mattis had or had not said, without bothering to check what he actually said (for details see previous blog post).

Wilkie's latest article begins reasonably enough by emphasing the importance of evidence when discussion chemical weapons in Syria but then completely ignores the vast body of evidence compiled by the UN and the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons – much of it based on laboratory tests.

Instead, he suggests the only available evidence comes from "the quasi-paid promotional material of regime change boosters" and regurgitates a long-discredited claim about bombs accidentally hitting chemicals stored on the ground.

Perhaps Newsweek imagines that articles of this sort contribute to public debate, but they don't. At least, not informed debate.

The Syrian conflict's anti-propaganda propagandists

Blog post, 24 February 2018: In times of war it's important but often difficult to distinguish truth from propaganda. So the newly-formed "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" – comprising three professors, two lecturers and three postgraduate researchers at British universities – ought to be a welcome development.

"At present," the group say, "there exists an urgent need for rigorous academic analysis of media reporting of this war, the role that propaganda has played in terms of shaping perceptions of the conflict and how these relate to broader geo-strategic process within the [Middle East] region and beyond."

The group's aim, they continue, is to "encourage networking amongst academics as well as the development of conference papers and panels, articles and research monographs, and the development of research funding bids. We also aim to provide a source of reliable, informed and timely analysis for journalists, publics and policymakers."

So far, so good. But on closer examination the working group itself seems more like a propaganda exercise than a serious academic project.

Published articles by leading members of the group give plenty of clues as to what the project is really about. They dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation. They are critical of western governments, western media and various humanitarian groups but show little interest in applying critical judgment to Russia's role in the conflict or to the controversial writings of several journalists who happen to share their views.

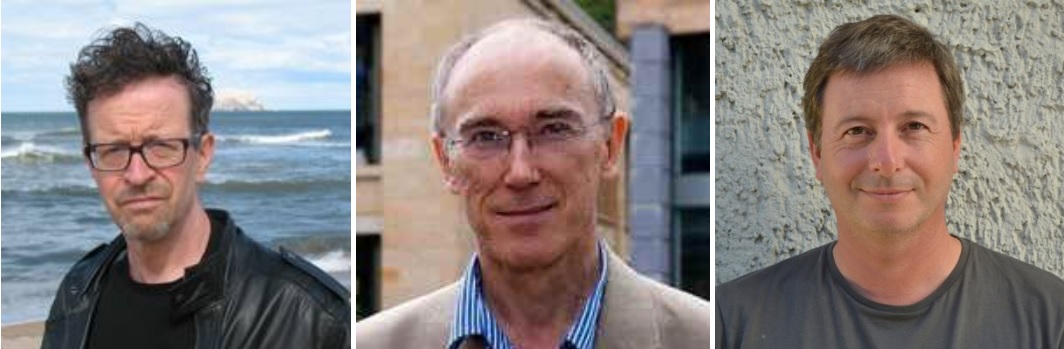

The group's steering committee consists of Tim Hayward, Professor of Environmental Political Theory at Edinburgh universiy, Paul McKeigue, Professor of Genetic Epidemiology and Statistical Genetics (also at Edinburgh) and Professor Piers Robinson, Chair in Politics, Society and Political Journalism at Sheffield university.

On the Edinburgh university website Prof Hayward's iconoclastic postings about "how we were misled" over Syria" include critiques of Amnesty International, Médecins Sans Frontières and the British Channel 4 News. There's plenty more, in a similar vein, on his personal website.

Probability theory

Meanwhile, two articles on the question of chemical weapons in Syria by Prof McKeigue (here and here) adopt a highly original approach – original to the point of absurdity. Using "probability calculus", with some assistance from Bayes’ theorem and Hempel’s paradox, McKeigue evaluates various hypotheses regarding the events in Ghouta (2013) and Khan Sheikhoun (2017).

He concludes there is "overwhelming" evidence that these were not chemical attacks by the Assad regime but "a managed massacre of captives [by rebels], with rockets and sarin used to create a trail of forensic evidence that would implicate the Syrian government in a chemical attack".

This, he adds, "has quite radical implications for the credibility of western media, western governments and international agencies such as OPCW [Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons]; you may reasonably ask 'how could they have got it so wrong?'."

At Sheffield university, Prof Robinson is also a chemical weapons sceptic (though in a more conventional way) and a critic of the White Helmets. He views the Syrian conflict as part of a western strategy of regime change dating back to the 2003 Iraq war:

"The bottom line here is that, given their desire for regime change in Syria, and for precisely the same reasons that intelligence was spun in the Iraq case, there are powerful incentives for western governments to distort and exaggerate in the case of Syria in order to create the casus belli they so desperately want ...

"With respect to Syria, it is now well established that there have been significant propaganda activities designed to manipulate public opinion in support of western regime change objectives."

Other members of the group, according to its website, are Dr Florian Zollmann, a lecturer in journalism at Newcastle university, Dr Tara McCormack, a lecturer in politics and international relations at Leicester university who also has a regular slot on Russia's Sputnik News, and three PhD candidates: Louis Allday (SOAS, University of London), Divya Jha and Jake Mason (both at Sheffield university).

Mason is working on a thesis entitled "Spinning Syria: The development and function of the British government's propaganda in the Syrian Civil War", supervised by Prof Robinson. The group's website was registered in Mason's name on January 25 this year.

'Rigorous academic analysis'

The "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" is essentially a campaigning organisation. Its members, of course, have a right to express their opinions and promote them through activism. The worrying part, though, especially in the light of their stated intention to seek "research funding", is their claim to be engaging in "rigorous academic analysis" of media reporting on Syria.

If that's the aim, the same level of academic rigour needs to be applied across the board, But while members of the group are generally very critical of mainstream media in the west, a handful of western journalists – all of them controversial figures – escape similar scrutiny. Instead, their work is lauded and recommended.

One of the journalists is Max Blumenthal whose views on the white helmets (here and here) are shared by the working group. The two favourites, though, are Eva Bartlett and Vanessa Beeley – "independent" journalists who are frequent contributors to the Russian propaganda channel, RT. Bartlett and Beeley also have an enthusiastic following on "alternative" and conspiracy theory websites though elsewhere they are widely dismissed as propagandists. Either way, their activities are part of the overall media battle regarding Syria and any "rigorous academic analysis" of the coverage should be scrutinising their work rather than promoting it unquestioningly.

Russia's role

The working group also claims to be researching "the role that propaganda has played in terms of shaping perceptions of the conflict and how these relate to [the] broader geo-strategic process". It's difficult to see how that can be done without taking into account Russia's propaganda strategy and its efforts to influence opinion in the west.

Prof Robinson has a rather charitable view of Russia's English-language media, such as RT and Sputnik News. He doesn't deny they are propaganda channels but objects to the idea that western media are somehow different. Writing in the Guardian, he says:

"Whatever the accuracy, or lack thereof, of RT and whatever its actual impact on western audiences, one of the problems with these kinds of arguments is that they fall straight into the trap of presenting media that are aligned with official adversaries as inherently propagandistic and deceitful, while the output of 'our' media is presumed to be objective and truthful. Moreover, the impression given is that our governments engage in truthful 'public relations', 'strategic communication' and 'public diplomacy' while the Russians lie through 'propaganda'."

He goes on to say: "One can gain useful insights and information from a variety of news sources – including those that are derided as 'propaganda' outlets: Russia Today, al-Jazeera and Press TV should certainly not be off-limits." Separately, when various British politicians were criticised for appearing on RT, Robinson rose to their defence:

"People are coming on RT in order to express legitimate political views and they are coming onto RT because they are probably having great difficulty getting onto existing ‘legitimate’ mainstream media in the west. In many ways RT is providing an important outlet for these people who are not getting their voices heard elsewhere."

But Putin clearly doesn't fund RT in order to support free speech, and suggesting the key difference between western propaganda and Russian propaganda is in the way they are perceived misses an important point. The Russians have been developing new propaganda techniques for the internet age and applying them to the Syrian conflict – which is one reason why they are worth studying.

RT's slogan is "Question More" – and it's brilliantly mischievous, because questioning more sounds like something we all should be doing. Scepticism is healthy, but only up to a point. Obviously, people should be encouraged to view media – in the west as elsewhere – with a critical eye and look out for attempts to manipulate them. Problems start, though, when people become so sceptical that they can't recognise truth when it's presented to them.

This is where RT's mischief-making comes in. Questioning more – Moscow style – is about manufacturing uncertainty.

Examples of the technique can be seen in Russia's response to the shooting down of flight MH17 over Ukraine and the chemical attacks in Syria. The trick is to cast doubt on rational but unwelcome explanations by advancing multiple alternative "theories" – ideas that may be based on nothing more than speculation or green-ink articles on obscure websites.

It doesn't much matter if some of the theories are mutually contradictory or highly fanciful, because the purpose is not to persuade people that any particular theory is correct, The point is to cause so much confusion that people have no idea what to believe.

This might seem like an obvious issue for the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media to be looking at. But don't hold your breath. Prof Robinson has already been complaining onTwitter about "the crazed obsession with Russia".

Manufacturing doubt over chemical weapons in Syria

Blog post, 27 February 2018: At a recent meeting of the UN security council Syria claimed the US and France now doubt that the Assad regime has ever used chemical weapons. The claim was false but it provides an interesting example of how propaganda can be created.

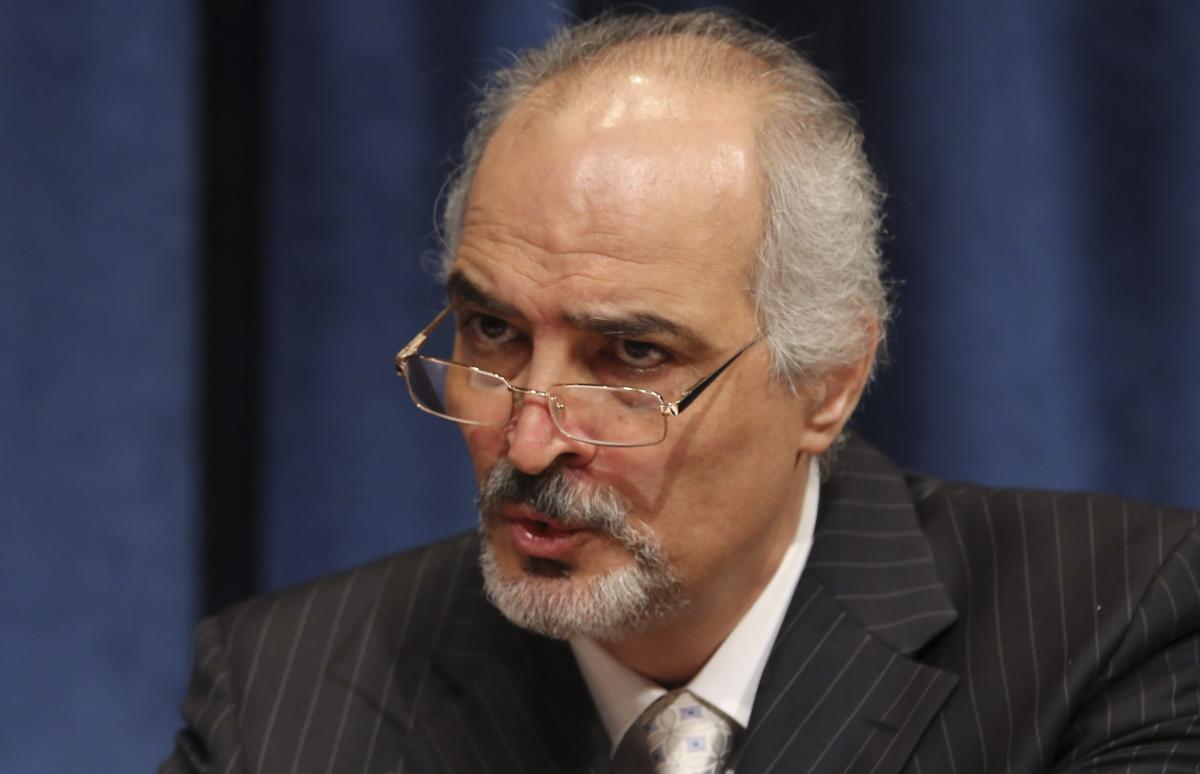

Speaking on February 14, Syria's representative at the UN, Bashar Ja'afari, told the council:

"One of the most important political magazines, the American Newsweek, published an article on 8 February written by Ian Wilkie entitled 'Now Mattis Admits There Was No Evidence Assad Used Poison Gas on His People'.

"The United States Secretary of Defence admits in that article that there is no proof of the use of toxic gas by the Syrian government against its people, neither in Khan Shaykhun [last year] nor in Al-Ghouta in 2013."

Mattis had said no such thing. In fact, he said the Assad regime was to blame for both attacks.

Laboratory tests by the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW) have previously established that the sarin involved was of a type manufactured by the regime.

Ja'afari's claim arose out of a news conference at the Pentagon on 2 February where Mattis was questioned about reports of recent chemical attacks in Syria using chlorine.

"Is this something you're seeing that's been weaponised?" a reporter asked.

"It has," Mattis replied, adding that the deadly nerve agent sarin may have been used too: "We are more – even more concerned about the possibility of sarin use, the likelihood of sarin use, and we're looking for the evidence."

Mattis explained that there were "reports from the battlefield" from people who claimed sarin had been used. but added: "We do not have evidence of it. But we're not refuting them; we're looking for evidence of it."

He said the American suspicions of renewed sarin use arose partly out of the Assad regime's previous behaviour: "they were caught using it" during the Obama administration (a reference to the Ghouta attacks in 2013) and "they used it again" after Trump became president (Khan Sheikhoun in 2017).

Mattis's phrase, "We do not have evidence", was clearly referring to the allegations of new chemical attacks but the Russian propaganda channel, RT, latched on to it and re-purposed it in a report which began:

"Washington has no evidence that the chemical agent sarin has ever been used by the Syrian government, Pentagon chief James Mattis has admitted" (italics added).

A few days later Newsweek magazine published a similar claim, with an article headed: "Now Mattis admits there was no evidence Assad used poison gas on his people".

The article's author, Ian Wilkie, described Mattis's "no evidence" statement as "striking" and continued:

"Mattis offered no temporal qualifications, which means that both the 2017 event in Khan Sheikhoun and the 2013 tragedy in Ghouta are unsolved cases in the eyes of the Defense Department and Defense Intelligence Agency."

This was completely untrue, as Wilkie would have seen if he had bothered to check the transcript of the news conference. Despite numerous people pointing out Wilkie's error, Newsweek did not withdraw the article or add a correction. Instead, 10 days later, it published a second article from Wilkie claiming "the Assad regime’s culpability is vastly under-proven by the public evidence". Newsweek described Wilkie as "an international lawyer and terrorism expert and a veteran of the US Army (Infantry)".

'Corroboration' from France

In his speech to the UN, Ja'afari then went on to claim Mattis's misreported words had been corroborated by France:

"The French Minister of Defence, Florence Parly, also said yesterday, like her American counterpart, that there is no documented proof of the use of chlorine gas by the Syrian Government."

A closer look, though, shows that Parly's words had also been twisted.

Last May, shortly after becoming president of France, Emmanuel Macron said he viewed chemical weapons as a red line: "Any use of chemical weapons would result in reprisals and an immediate riposte, at least where France is concerned."

In a radio interview on 9 February, armed forces minister Parly was asked, in the light of fresh reports about chemical attacks, if Macron's red line had now been crossed. (The original transcript in French is

here.)

Interviewer: Do you have confirmation, I mean confirmation, that barrels of chlorine have been used by Syrian regime forces against Syrian civilians?

Minister: We have possible indications of chlorine use, but we do not have absolute confirmation, so it is this confirmation work that we are doing, with others elsewhere, because obviously the facts must be established.

Interviewer: Last May Emmanuel Macron indicated that a very clear red line – I'm quoting – existed on our side, on the side of France, and therefore use of a chemical weapon by anyone – I'm still quoting the president – would be the object of reprisals and an immediate response from the French. We are there, aren't we?

Minister: Exactly, we can't say it with certainty, and that is what we must achieve.

Interviewer: So, for the moment, for lack of proof, the red line has not been crossed?

Minister: For the moment, for lack of certainty about what has happened, about the consequences of what has happened, we cannot say that we are there ...

Use of chlorine as a chemical weapon is more difficult to confirm than sarin through laboratory tests, which may partly explain the French minister's hesitancy.

In 2014, however, a fact-finding mission from the OPCW concluded "with a high degree of confidence" that chlorine had been used:

"Thirty-seven testimonies of primary witnesses, representing not only the treating medical professionals but a cross-section of society, as well as documentation including medical reports and other relevant information corroborating the circumstances, incidents, responses, and actions, provide a consistent and credible narrative.

"This constitutes a compelling confirmation that a toxic chemical was used as a weapon, systematically and repeatedly, in the villages of Talmanes, Al Tamanah, and Kafr Zeta in northern Syria. The descriptions, physical properties, behaviour of the gas, and signs and symptoms resulting from exposure, as well as the response of the patients to the treatment, leads the FFM [Fact-Finding Mission] to conclude, with a high degree of confidence, that chlorine, either pure or in mixture, is the toxic chemical in question."

A further report provided more detail.

Russia-friendly 'Syria propaganda' group names more supporters

Blog post, 6 March 2018: The newly-formed "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" – which I wrote about last month – has added some further names to its list of members and advisers.

The group claims to be promoting "rigorous academic analysis" of propaganda in the Syrian conflict and says it aims to "provide a source of reliable, informed and timely analysis for journalists, publics and policymakers".

The 14 members and advisers named on the group's website are academics – mostly at British universities – and the group says it intends to bid for research funding.

However, published articles by members of the group cast doubt on their claims of "rigorous academic analysis". They dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation.

They are critical of western governments, western media and various humanitarian groups but show little interest in applying critical judgment to Russia's role in the conflict. One of their members, Dr Tara McCormack of Leicester university, has a regular slot on Russia's Sputnik News.

Members of the group uncritically cite work by Eva Bartlett and Vanessa Beeley – two "independent" journalists who have an enthusiastic following on "alternative" and conspiracy theory websites but are widely regarded elsewhere as propagandists.

The group's most recent new member is Irish-born Oliver Boyd-Barrett, an emeritus professor at Bowling Green State University in Ohio.

Boyd-Barrett has written or contributed to numerous books about the media, including one on "media imperialism" and one on the globalisation of news.

Another of his books, Western Mainstream Media and the Ukraine Crisis: A Study in Conflict Propaganda has a chapter about the shooting-down of Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 over Ukraine in 2014.

Boyd-Barrett devotes much of the chapter to casting doubt on reports about the crash in western media. He concludes that the "preponderance of evidence" seems to "support the contention that MH17 was brought down by a missile fired from a Russian-made BUK" but says "full consensus as to the facts may never be achieved".

He goes on to say the MH17 crash (which killed 298 people) "has been deployed as a red herring to distract attention from the main issues concerning the Ukraine crisis ... and, instead, beating up a lather of western public repugnance for Russia in general, Vladimir Putin in particular, and the ethnic Russian separatists of Eastern Ukraine."

In addition, he accuses the Ukrainian authorities of "criminal negligence" for failing to close their airspace to civilian flights.

The chapter also talks about "comparable false confidence alleging Assad's use of chemical weapons in Syria", saying such claims have been "refuted" by Richard Lloyd and Ted Postol of Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media says it is in the process of setting up an "International Advisory Board" and lists five names on its website.

One of these is Iraqi-born Sami Ramadani, described as an "independent researcher". Ramadani is better known as a prominent member of the Stop the War Coalition (STWC) where he serves on the steering committee.

Ramadani has also made numerous appearances on the Russian propaganda channel, RT.

STWC has been embroiled in controversy during the Syrian conflict because of its reluctance to criticise actions by Russia and the Assad regime.

Its "Anti-War Charter" calls for "an end to foreign policy based on Washington’s global ambitions or on a junior imperial role for Britain" but it also calls for "an immediate initiative to de-escalate tension with Russia".

In 2013, STWC invited Mother Agnes, a Syrian-based nun who was sympathetic towards the regime, to speak at one of its conferences. Mother Agnes, who was sympathetic towards the Assad regime, had produced a report disputing the authenticity of videos showing victims of sarin attacks.

Three of the videos, she said, showed "artificial scenic treatment using the corpses of dead children", while in others she suggested the children were anaesthetised or merely sleeping. Human Rights Watch dismissed Mother Agnes's claims as baseless but the Russian propaganda channel, RT, continued to treat her as a quotable source.

Two other speakers at the STWC conference refused to share a platform with her and she eventually withdrew.

Besides Ramadani, others named as members of the advisory board for the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media are Dr Christopher Davidson (University of Durham, UK), Professor Richard Jackson (University of Otago, New Zealand), Professor Richard Keeble (University of Lincoln, UK) and Professor Roger Mac Ginty (University of Manchester, UK).

UPDATE, 7 March 2018: Today, the working group added three more names to its website. Dr Greg Simons (Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University) is an additional member. Professor Philip Hammond (London South Bank University) and Professor Mark Crispin Miller (New York University) have been added to the "International Advisory Board". Sami Ramadani's description has been changed to "retired Academic".

UPDATE, 8 March 2018: Today the name of Professor Roger Mac Ginty was removed from the group's website.

From Syria to Salisbury: Russia's propaganda game

Blog post, 15 March 2018: There's something uncannily familiar about Russia's propaganda antics over the poisoning of double agent Sergei Skripal in Britain. We've seen them before in Syria where Russia has steadfastly defended the Assad regime against accusations of using chemical weapons.

On an August morning in 2013 news began to emerge of mass deaths in Ghouta on the outskirts of Damascus. A report from Reuters began: "Syria’s opposition accused government forces of gassing hundreds of people on Wednesday by firing rockets that released deadly fumes over rebel-held Damascus suburbs, killing men, women and children as they slept."

Right from the start, there was little doubt about what had happened: videos of those affected showed classic symptoms of nerve agent poisoning. Within a month, UN inspectors confirmed the worst: the environmental, chemical and medical samples they had collected provided "clear and convincing evidence that surface-to-surface rockets containing the nerve agent sarin" had been used in Ghouta.

Sowing doubt

Given that these deaths and injuries occurred in rebel-held areas that were under attack from Syrian government forces and that the government had previously admitted possessing chemical weapons, there was one very obvious suspect. But Russia had other ideas.

Its first response was to question whether anything untoward had actually happened. On the day of the attack, an article posted on the Russia's RT website described the reports as "fishy" and claimed that international media had simply "picked up" the story from al-Arabiya, a Saudi TV channel which was "not a neutral in the Syrian conflict".

Meanwhile, Russia's foreign ministry spokesman, Aleksandr Lukashevich, hovered between denying an attack had taken place and claiming it had been staged (or perhaps faked) by anti-Assad forces. He talked about an "alleged" attack and a "so-called" attack while asserting that "materials of the incident and accusations against government troops" had been posted on the internet several hours in advance. "Thus, it was a pre-planned action," he said.

Lukashevich's argument had actually been cribbed from conspiracy theorists on the internet, but without checking properly. Reuters' report of the attack and some of the videos did appear to have been posted before the attack took place but that was simply the result of automated time-stamping in a different time zone.

Following publication of the UN inspectors' report, Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov acknowledged that it showed chemical weapons had been used but said it offered no proof that Assad's forces were to blame. This implied the inspectors had failed to reach a conclusion about who was responsible but the terms of reference set by the UN had not allowed them to apportion blame.

Diversionary tactics

Lavrov went on to say that Russia still suspected rebel forces were behind the attack and that the UN report failed to answer a number of questions, including whether the weapons were produced in a factory or "home-made". He added that the UN report should be examined not in isolation but along with evidence from sources such as the internet and other media, including accounts from "nuns at a nearby convent" and a journalist who had spoken to rebels.

The questions Lavrov raised – about home-made sarin, the nuns in the convent and the journalist who had spoken to rebels – looked suspiciously like a diversionary tactic, and that is what they were. They didn't withstand serious scrutiny but in propaganda terms they didn't need to. The point was not to persuade people of anything in particular – which was one reason why many people had difficulty recognising it as propaganda.

The slogan of RT is "Question More", and its purpose is exactly that: to ask lots of questions, not in the hope of getting closer to the truth but in order to sow as much doubt as possible. This doesn't require real evidence and it doesn't matter if some of the "alternative" theories promoted are mutually contradictory or purely speculative, so long as there are plenty of them. If the result is that people become so confused they are unsure what to believe the propaganda can be considered a success.

Russia's propagandists also have a symbiotic relationship with conspiracy websites in the west which not only re-circulate and amplify the theories but sometimes generate them in the first place.

False flags in Salisbury?

Fast-forward to March 2018 and the English city of Salisbury where Sergei Skripal and his daughter, Yulia, were poisoned. As with Syria in 2013, there was one rather obvious suspect. The Skripals were Russian. Sergei had been a double agent in the murky world of espionage, and as far as Russia was concerned had betrayed his country.

Over the last 40 years a number of mysterious deaths in Britain have been linked to Russia or its predecessor, the Soviet Union. At least two of those involved murder by exotic means – Georgi Markov in 1978, stabbed with a ricin-tipped umbrella, and Alexander Litvinenko in 2006 who was killed with radioactive polonium. There have been other cases too, outside Britain.

Sergei and Yulia Skripal were found on a park bench "reportedly exhibiting symptoms similar to a drug overdose" according to Russia's RT. Another RT article suggested they might be drug users.

Amid the initial speculation about what might have caused the Skripals' poisoning, there was talk in several British newspapers that the substance involved might be fentanyl, a powerful opiate. One factor behind that idea was that fentanyl, or a version of it, is thought to have been used by Russian special forces to subdue Chechen separatists who held 800 people hostage at a Moscow theatre in 2002 (as the Sun newspaper pointed out). RT, however, had a different spin on the fentanyl angle:

"The highly addictive synthetic opiate has been linked to a sharp increase in overdoses in the US and has also resulted in dozens of deaths across the UK. The drug has repeatedly made headlines as part of the so-called ‘opioid crisis’, especially after famous American singer/songwriter Prince died from an accidental overdose of fentanyl in April 2016.

"An eyewitness told the BBC she saw a woman and a man sitting on a bench and that they 'looked like they’d been taking something quite strong'."

Since then, the Russians have moved on from trying to deny that a nerve agent attack took place, as they did in Syria over sarin. They are now promoting multiple "false flag" theories – as they also did in Syria over sarin. Daft as the theories might be, in Syria's case they found some vocal supporters in the west – and the same thing seems to be happening now with the Skripal affair.

"I think this will go down with the Gulf of Tonkin incident as one of the great hoaxes, with the most serious implications in all of history," former British MP George Galloway told Sputnik Radio's listeners.

With Syria, the main false flag theory was that rebels attacked themselves with sarin to create the pretext for a large-scale military intervention by western powers against the Assad regime. This was also linked to the dubious claim that western powers had spent years plotting "regime change" in Syria. Despite two confirmed sarin attacks, however, western powers have still not responded in the way the theory has been predicting.

With the Skripal affair, Russia is strongly suggesting a false flag operation carried out by the British government but is unclear about its exact purpose.

Galloway, who became notorious for his tribute to Saddam Hussein in 1994, suggested it might have something to do with Putin's re-election or the World Cup (which is due to be held in Russia this summer). The Russian foreign ministry also appears to favour a World Cup connection: the British are "unable to forgive" Russia for winning the right to host this summer's contest.

More vaguely, Sputnik quotes Helga Zepp-LaRouche – leader of the German Bürgerrechtsbewegung Solidarität party and wife of the controversial American, Lyndon LaRouche – as blaming British intelligence for "fabricating another Litvinenko case as a pretext for another anti-Russia escalation". It's unclear why Sputnik regards her as an authority on the matter.

While mainly trying to direct suspicion towards Britain, the Russians are also speculating that some other country might be the culprit – almost any country apart from Russia. According to a former Kremlin adviser quoted by Sputnik News, "every laboratory in the west including Porton Down which is only seven miles away from Salisbury, has a sample" and there are "are rouge agents of a different nation that have gotten access to this particular nerve agent". The mention of "rouge" (rogue) agents may be intended as a reference to Ukraine.

These ideas have already acquired some resonance at the further ends of the political spectrum (both left and right) in the west. Look on Twitter and you will find that many of those adopting them have previously been active in questioning the Assad regime's sarin use.

Not surprisingly, there have been calls to cancel RT's television broadcasting licence in Britain – which would probably be a mistake. RT would have a field day complaining about being victimised, and blocking its TV output would have little practical effect. RT would still be able to function online, which in some ways may be more important because its propaganda is often circulated in the form of YouTube videos.

No matter what anyone does to try and stop it, though, propaganda will always exist. The important thing is to recognise it for what it is, and not to be fooled by it.

'Propaganda' professors switch focus from Syria to Britain and Russia

Blog post, 18 March 2018: A group of university professors who promoted conspiracy theories about chemical weapons in Syria are now making similar claims about the recent chemical attack in Britain which critically injured Russian double agent Sergei Skripal and his daughter.

The "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" was set up in January, comprising professors and other academics from universities in Britain, the US, Sweden and New Zealand.

It purports to be engaged in "rigorous academic analysis" of media reporting of the Syrian conflict and the role played by propaganda, but on closer examination the group itself seems more like a propaganda exercise than a serious academic project.

Previously published articles by members of the group cast doubt on their claims of "rigorous academic analysis". They dispute almost all mainstream narratives of the Syrian conflict, especially regarding the use of chemical weapons and the role of the White Helmets search-and-rescue organisation. Several of the group also make frequent appearances on the Russian propaganda channels, RT and Sputnik.

Last week the group published its first "working paper" and, rather oddly, it was not about Syria but about Britain and Russia.

The paper, co-authored by Professor Paul McKeigue of Edinburgh University and Professor Piers Robinson of Sheffield University, claims the British government has developed a way of producing the "novichok" compound that poisoned the Skripals.

Since the first confirmed use of a nerve agent in Syria in 2013, defenders of the Assad regime – and especially the Russian government – have been claiming it was a "false flag" attack by rebels, intended to discredit the regime.

Following the nerve agent attack in Britain earlier this month, similar "false flag" claims have been circulating on the internet, suggesting the British government carried it out in order to stir up public opinion against Russia. Russian propaganda channels have been eagerly promoting that idea too.

In their working paper, Paul McKeigue and Robinson point to a possible British source for the nerve agent. "Porton Down [the British research establishment] must have been able to synthesize these compounds in order to develop tests for them," they say (italics added).

Their claim, though, is simply wrong. Being able to test for a particular compound does not require an ability to produce it.

The working paper is also at pains to question whether Russia could have produced a "military grade" version of the nerve agent, though the relevance of that is unclear. There would be no need to have developed it for battlefield purposes in order to use it against two individuals in Salisbury.

Prof Robinson, who teaches journalism studies at Sheffield, had a busy time last week. He also appeared on both RT and Sputnik talking about the Skripal affair. In addition, his group's working paper about novichoks was featured in an article on Sputnik's website where he was described as an academic "with knowledge of chemical weapons".

Robinson's co-author, Paul McKeigue, is Professor of Genetic Epidemiology and Statistical Genetics at Edinburgh. In a previous publication, McKeigue deployed Bayes’ theorem and probability theory to claim there is "overwhelming" evidence that rebels in Syria used the nerve agent sarin at Ghouta in 2013 and Khan Sheikhoun in 2017. He managed to reach that conclusion even though the sarin used on both occasions was of a type made by the Syrian government and there is no credible evidence that the rebels ever possessed sarin.

Another prominent member of the "Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media" is Tim Hayward, Professor of Environmental Political Theory at Edinburgh University, who re-posted the article by Robinson and McKeigue on his personal website.

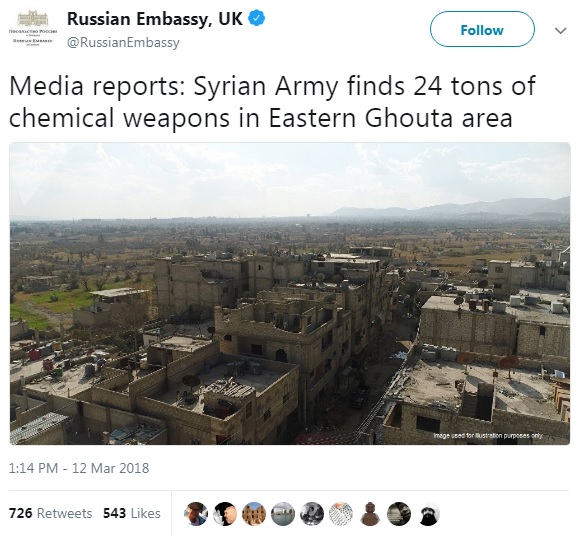

On Monday he re-tweeted a statement from the Russian embassy in London claiming that the Syrian army had found "24 tons of chemical weapons" in an area of Ghouta previously held by rebels.

Hayward commented: "You can see why the British elite do not want us getting any news via Russia" and it was indeed easy to see why – because the Russian claim was demonstrably false.