During the last few days key elements of Yemen's national army have turned their backs on the main enemy – the Houthis – and moved south to confront allies in the anti-Houthi coalition.

Tensions between forces supporting the ousted "legitimate" government of President Abd Rabbu Mansour Hadi and southern separatists came to a head on Thursday night when they clashed in Ataq, the capital of Shabwa province.

Since then, reinforcements have been arriving from further north and the separatist forces appear to have been pushed back to a few kilometres south of Ataq.

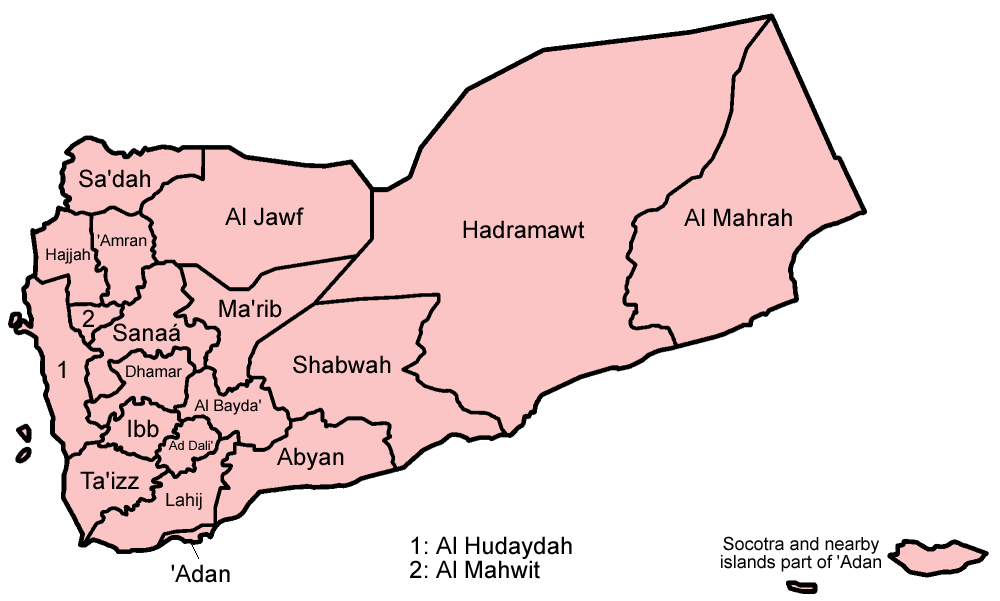

Meanwhile there's a claim – unconfirmed at the time of writing – of an attack by government forces at al-Ayn, near Lawdar (see map). If successful, this would cut the main road between Ataq and the port city of Aden which the separatists claim as their capital.

The southern issue in Yemen

More background on the conflict between separatists and the "legitimate" government

Both sides in this conflict are members of the Saudi-led coalition against the Houthis who control the capital, Sanaa, but there have been tensions between them for some time – tensions which are also reflected in the wider coalition. Saudi Arabia strongly supports the Hadi government. The UAE officially does so too but is less enamoured with Hadi and has also been training and supporting separatist militias in the south.

The current war-within-a-war began on 10 August when the separatists seized control of Aden on the grounds that the Hadi government's forces were failing to provide adequate protection. For several days they appeared to be making rapid gains elsewhere in the south until meeting fierce resistance in Ataq.

The separatists' basic claim is that they are better placed than anyone else to provide security in the south, and should be allowed to do so. But there is more to the security issue than meets the eye. If they can establish control of security across the south and start to provide services for the public they will have the rudiments of a future state – which is their ultimate goal.

However, they also have another reason for wanting to take control of security in the south. They believe this would give them significant leverage in discussions about the post-war shape of Yemen – a process from which they currently feel excluded. The problem at an international level, as the southerners see it, is that the Yemeni war is treated as a two-sided conflict – Houthis versus the "legitimate" government – and they seek to change that by establishing new facts on the ground.

The separatists want an independent southern state in line with the boundaries of the former People's Democratic Republic of Yemen (see map below).

On that basis the separatists claim the whole of Shabwa province is theirs, even though the northern part of it is in the hands of government forces. The government-held part has oil – which the separatists want – and Ataq is strategically placed on the route to the oilfields from the south.

Government forces, meanwhile, claim the right to deploy anywhere in Shabwa since the province forms part of military area 3, as designated by a decree from President Hadi in 2013.

In the midst of this, there's debate on social media about how much popular support the separatists have, and especially whether the two provinces to the east of Shabwa – Hadramaut and al-Mahra – would prefer to be part of a unified Yemeni state, part of an independent southern state, or have a mini-state of their own. The two provinces have a small population and Hadramaut has oil – so they would probably benefit economically by going their own way.

In a tweet on Saturday, Gerald Feierstein – a former US ambassador to Yemen – dismissed the idea that separatism has much support in the eastern part of the south. "The vision of pre-1990 South Yemen is confined to the southwest governorates (and not universal there either)," he wrote. "In Hadramaut, Mahra, and Socotra that’s not the goal. The risk of a deeply fractured Yemen is real and the UAE is playing with fire."

Replies to Feierstein from Hadramis show a variety of opinions. Here are some examples:

In a recent interview Amr al-Bidh, son of former southern leader Ali Salim al-Bidh, acknowledged that the two eastern provinces may not be enthusiastic about joining a southern state based in Aden. "We know that everyone wants to have their own governor," he said. "Hadramaut doesn't want to be ruled by Aden."

Al-Mahra, which borders Oman, is also "sensitive", he said. "Omanis are working there ... and the Saudis have their military there."

Currently, the government and the separatists appear to be competing for the allegiance of various tribal leaders and other important figures in the south.

Last week in Aden, for example, Major General Ahmed Said bin Brik, a leader of the separatist Southern Transitional Council received a delegation of the Al Kathir tribes from northern Hadramaut. On Saturday, however, the deputy governor of Hadramaut, Amru bin Habrish, posted a tweet declaring support for "the Arab coalition led by Saudi Arabia and its wise orientations". In light of "turbulent conditions", he said, "we are distancing Hadhramaut away from all these conflicts to remain safe and stable for its people".

RSS Feed

RSS Feed