Amnesty International has accused Bahrain and Kuwait of running "roughshod over people's privacy" in their use of surveillance technology during the coronavirus pandemic.

The human rights organisation carried out a detailed technical analysis of phone apps in seven Arab states plus France, Iceland, Israel and Norway.

It singled out those used by Bahrain, Kuwait and Norway as the most alarming, with all three "actively carrying out live or near-live tracking of users’ locations by frequently uploading GPS coordinates to a central server".

"They are essentially broadcasting the locations of users to a government database in real time," Amnesty says. "This is unlikely to be necessary and proportionate in the context of a public health response.

"Technology can play a useful role in contact tracing to contain Covid-19, but privacy must not be another casualty as governments rush to roll out apps."

CLICK HERE to jump to Middle East updates

Norway suspended use of its "Smittestopp" app after being presented with Amnesty's findings.

The World Health Organisation has also warned about potential dangers in such apps. In a report earlier this month it said:

"WHO recommends that users of digital tools should participate on a voluntary basis and that written consent is always obtained. Privacy concerns about the disclosure of personal data need to always be addressed. Data processing agreements must disclose which data are transmitted to third parties and for what purpose."

One fear is that the apps could be used to track people for non-medical purposes – such as monitoring of political dissidents by authoritarian regimes.

Coronavirus apps can use location data for several purposes connected with the pandemic. The most common one, related to contact-tracing, is to trigger an alert when app users come close to another user who is known to be infected. The less intrusive types of app just store this on the phone but others send the information to a central database where the authorities can make use of it – which is what the Bahraini and Kuwaiti apps do.

The WHO describes this technology as "proximity tracing" rather than "contact tracing", cautions against over-reliance on it and says its use should always be voluntary. "Digital tools should be considered a way to augment and optimise contact tracing rather than a replacement of contact tracing teams," it says.

"The potential contribution of proximity tracing tools depends on widescale adoption of the same tool, which in turn depends on people having a suitable smartphone that is always charged and working, has a reliable connection to a mobile network, and is always accessible to them. Over-reliance on proximity tracing tools may result in the exclusion of contacts such as children or people who do not have a suitable device."

Proximity alerts are not the only function of the Bahraini and Kuwaiti apps, however. Both countries have been repatriating thousands of citizens from abroad – all of whom need to be quarantined on arrival.

There are two options for quarantining these returnees. One is to confine them in supervised accommodation (as some countries, such as Jordan, have been doing). The other – less restrictive – option is self-quarantining at home and Kuwait's "Shlonik" is designed to monitor compliance with that:

"The app is linked with a smart bracelet in order to track movement and notify the [health] ministry if people break the quarantine rules ...

"The returnees are each given a bracelet upon their arrivals at the airports.

"Shlonik notifies the medical teams in the event of breaking home quarantine and sends questions to the quarantined twice a day regarding the symptoms of coronavirus such as cough, temperature, and shortness of breath.

"The app also asks the users to submit random selfies."

Bahrain's "BeAware" app is also used in combination with a bracelet when tracking people who are in compulsory home quarantine.

An alert is sent to the authorities if the wearer of the wristband moves more than 15 metres from the relevant phone. The health ministry can also carry out spot checks by demanding selfies from quarantined people showing both their face and the wristband.

Removing the wristband or tampering with it can result in a minimum jail sentence of three months, and/or a fine of 10,000 dinars ($26,000).

This is certainly intrusive but is it necessarily an abuse of human rights? It's not unreasonable to quarantine people compulsorily during an epidemic if they are potentially infected. Most would probably regard home quarantine as preferable to being locked in an isolation centre, and the apps allow that to happen while providing some safeguards against cheating.

Non-compliance has been a serious problem in most of the Middle East and the UAE has also been using mobile phone technology – though not an app – to monitor people's activity during its lockdown.

Under rules announced in April people were not allowed to leave their homes except for buying food and medicines and visiting a hospital or a doctor. To do that, though, they needed permission from the police.

The process began by registering their mobile phone number on a police website which then gave access to an online application form.

The form asked for their address, ID details, and car registration number. They also had to tell the police where they intended to go, at what time, and at what time they expected to return home. The process had to be repeated for every trip outdoors.

This of course made it much easier for the police to check if people on the streets had a permit and whether they were complying with its terms. Speed cameras were also adjusted to photograph all vehicles using the roads during the night curfew – even if they were not speeding.

The loss of privacy was scary, though its purpose can be defended as benign – protecting the public from a potentially deadly illness. But once the pandemic is over the technology will still be there. And who knows what purposes it might be used for then?

Further information:

Covid-19 in Bahrain

Covid-19 in Kuwait

Previous Middle East updates

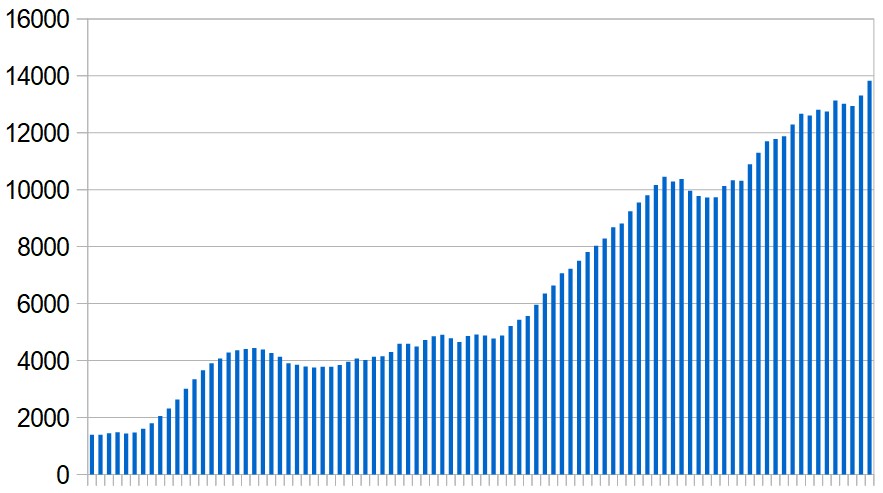

Covid-19 statistics for Middle East

Middle East updates

New cases

A further 14,084 Covid-19 infections have been reported in the Middle East and North Africa since yesterday's update.

Saudi Arabia reported the largest number of new cases – 4,267 – followed by Iran with 2,563.

The list below shows cumulative official totals since the outbreak began, with day-on-day increases in brackets.

Algeria 11,147 (+116)

Bahrain 19,553 (+540)

Egypt 47,856 (+1,567)

Iran 192,439 (+2,563)

Iraq 22,700 (+1,385)

Israel 19,637 (+299)

Jordan 981 (+2)

Kuwait 36,958 (+527)

Lebanon 1,473 (+9)

Libya 484 (+17)

Morocco 8,985 (+64)

Oman 26,079 (+810)

Palestine 700 (+10)

Qatar 82,077 (+1,201)

Saudi Arabia 136,315 (+4,267)

Sudan 7,740 (+305)

Syria 177 (-)

Tunisia 1,125 (+15)

UAE 42,982 (+346)

Yemen 889 (+41)

TOTAL: 660,297 (+14,084)

Note: The list above was amended on 18 June 2020 to correct the figures for Kuwait. Yemen's total includes four cases reported by the unrecognised Houthi government in the north of the country. Palestine's total includes East Jerusalem.

Death toll

A further 354 coronavirus-related deaths were reported in the region.

The day's highest reported death tolls were in Iran (115), Egypt (94) and Iraq (60).

The list below shows cumulative official totals with day-on-day increases in brackets.

Algeria 788 (+11)

Bahrain 47 (+1)

Egypt 1,766 (+94)

Iran 9,065 (+115)

Iraq 712 (+60)

Israel 303 (+1)

Jordan 9 (-)

Kuwait 306 (+8)

Lebanon 32 (-)

Libya 10 (-)

Morocco 212 (-)

Oman 116 (+2)

Palestine 5 (-)

Qatar 80 (+4)

Saudi Arabia 1,052 (+41)

Sudan 477 (+9)

Syria 6 (-)

Tunisia 49 (-)

UAE 293 (+2)

Yemen 215 (+6)

TOTAL: 15,543 (+354)

Note: Yemen's total includes one death reported by the unrecognised Houthi government in the north of the country.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed