GNRD and the Lord of Scientology

25 July 2016: GNRD, the strange "human rights" organisation that was declared bankrupt earlier this month, had an unusually favourable view of human rights in the UAE. It was also on friendly terms with Egypt's Sisi regime and the Kurdish PYD. Another of its friendships, though – and one which it sought to keep quiet about – was with the Church of Scientology.

The central figure in the relationship was a leading British Scientologist. Duncan McNair – a hereditary peer officially known as the 3rd Baron McNair – provided GNRD with "consultancy" services. He had a dual role as the organisation's "UK Public Affairs Adviser" and internationally as an "education and political PR" consultant. However, his involvement was not welcomed by all of GNRD's employees, most of whom were Muslims.

In February last year GNRD staff attended "human rights training" workshops in London. The workshops, conducted by McNair himself, took place at Fitzroy House, a museum dedicated to the memory of Scientology's founder, L Ron Hubbard. GNRD reported the workshops on its website at the time but without any mention of the Scientology connection; it described Hubbard merely as an "American writer and philosopher".

A few days later GNRD returned to the Hubbard museum for a celebration of International Women's Day. The keynote speaker at that event was Mary Shuttleworth, the founder and president of Youth for Human Rights International, one of Scientology's numerous front organisations. Again, GNRD reported this on its website without a word about Scientology.

GNRD did mention McNair by name but described him as "a member of the Liberal Democrats Party, which is one of the two parties in the British coalition government" [as it was at the time]. However, it is more than 16 years since McNair was an active politician and he is better known in Britain as a Scientologist.

McNair took up a seat in the House of Lords in 1990 after inheriting the Baron title from his father. In 1996, during a speech in the Lords, he came out as a Scientologist – the first British parliamentarian to do so. He also made a series of interventions in the Lords which were seen as supporting Scientology but this came to an end in 1999 when the Labour government's reforms reduced the number of hereditary peers who were allowed to take part in House of Lords business. McNair was one of those excluded.

Currently, McNair seems to be mainly working as a consultant. A London-based company called Alchemy Business Management lists him as its "President & Chief Operations for non Profit Sector". A profile on its website says:

"Lord Duncan McNair was a Member of the House of Lords from 1990 to 1999 where he focused on humanitarian issues, campaigning strongly on natural health and education. Since that time Lord McNair has been and continues to be a public affairs consultant to commercial clients and charities and has successfully managed projects for those clients in the fields of consumer products, infrastructure maintenance, international development and human rights.

"He is currently consulting to the Global Network for Rights and Development [GNRD] ... as their UK Public Affairs Adviser and internationally as an education and political PR consultant."

(The profile also describes GNRD as "an international NGO that has UN contracts for ensuring that aid funds are properly used" – which will probably come as news to the UN.)

McNair also has a consultancy called Strategic Resolution ("Communication Strategy in Business and Politics") based at his home in East Grinstead. Describing its "ideal clients", Strategic Resolution says:

"You adhere to the highest standards of honesty and integrity. If you want to succeed by taking unethical shortcuts, we're not for you. If you want to play the game at the highest level, we'd like help you achieve the success you are aiming for."

Apart from the meetings at the Hubbard museum in London there is no further mention of McNair on GNRD's website. However, videos posted on YouTube show him taking part in other GNRD events. One, from May last year, shows him at a media workshop in GNRD's Norwegian headquarters – just a few days before the premises were raided by police in connection with money-laundering allegations. (The case has yet to come to court and GNRD denies wrongdoing.)

GNRD's media workshop in Norway. Lord McNair first appears 23 seconds from the start

Another video shows McNair with GNRD's contingent at the UN Human Rights Council session in Geneva in March this year.

GNRD video from the UN Human Rights Council session last March. Lord McNair can be seen at 2 minutes 10 seconds.

Thomas Bechmann, who was employed by GNRD as a film producer, had been taking photos and making videos of the activities in Geneva and recalls that when he set off for home McNair asked to take possession of them.

"I took photos and recorded everything they did," Bechmann told al-bab. I left about a week before the others and then Duncan [McNair] – he was with us the whole time – asked for the footage and pictures. So I said yes. He was with us, like every day, coming to meetings and stuff.

"I gave it to him and then when I was back in Norway someone [a colleague] asked me for photos or pictures and I said 'Just ask Duncan, because he has everything'."

According to Bechmann, the colleague responded: "Why are you giving him everything? He sends emails to employees with Scientology propaganda."

Bechmann, however, did not see that as a logical reason for refusing to hand over the pictures to McNair, adding that McNair had never tried to recruit him to Scientology: "I talked a lot to Duncan and he never once mentioned Scientology or anything like that."

Bechmann later initiated the bankruptcy case against GNRD when it stopped paying his wages.

Award for an Emirati

Aside from McNair there is a further connection between GNRD and Scientology which may or may not be coincidental. Norwegian police believe almost all of GNRD's funding came via the United Arab Emirates but so far details of only one Emirati payment have become public. A document leaked to al-bab last August shows a transfer of 100,000 euros to GNRD from Al-Mezmaah Studies and Research Center in Dubai.

Al-Mezmaah describes itself as "an independent centre established by Dr Salem Humaid with the aim of concentrating on the regional affairs of the United Arab Emirates and also its repercussion at the Arab and international level and all that which exalt the name of the United Arab Emirates".

Humaid, the founder of al-Mezmaah, has held various government posts in Dubai – most notably with the Dubai Culture and Arts Authority. According to a Scientology website, the Scientologists received an award from the Dubai Culture and Arts Authority "in recognition of Mr Hubbard’s vision of a world where arts and the artist may flourish". Exactly when that happened, or what prompted it, is unclear.

Humaid, meanwhile, received an award from the Scientologists. In 2010, he became the first Arab ever to be named as their "Culture Person of the Year". The title was bestowed on him at the Scientologists' "Writers of the Future" awards ceremony in Hollywood. A report of this event also said Humaid had been chosen to "supervise the Arabisation" of books by Ron Hubbard.

McNair and human rights

McNair has a family connection with the Middle East. During the 1950s his grandfather, Sir Arnold McNair – the first Baron McNair – was a judge at the international court in The Hague who sided with Iran in a legal battle with the British government. A website run by Duncan McNair says:

"Iran had enjoyed a democratic government since 1906. In 1952, after making considerable but fruitless efforts to negotiate a fairer share of the oil revenues for the country and its people, Iran’s elected Prime Minister, Mohammed Mossadegh, nationalised the oil country’s oil industry, basically the oil assets of what is now British Petroleum, or BP.

"The British Government tried to bring a case against the Iranian Government but the Court decided by nine votes to five that it had no jurisdiction to try the case ...

"Sir Arnold wrote a paper supporting the Iranian position which no doubt helped to convince the Court to take the view it did. The Americans and British decided on regime change and organised a coup against the elected Government of Prime Minister Mohamed Mossadegh. When Iranians meet to discuss this episode in their history they remember the support of Sir Arnold McNair."

According to the same website Duncan McNair was invited to give a talk about his grandfather to an Iranian exiles group in London called Tribon-e-Azad. The discussion turned to questions of democracy and McNair produced some "human rights education materials" which he had brought along to the meeting.

"From that we started human rights education in Farsi," the website says. "Now the educational materials have been translated into Arabic, Farsi, Kurdish, Turkish and Urdu."

It appears that these materials, or something very similar, were also used for the "training workshops" attended by GNRD.

McNair has since established a project called Peaceful Planet which is described as "an educational programme teaching the Universal Declaration of Human Rights". A note from McNair on its website thanks Youth for Human Rights International (a Scientology front) and its sister organisation, United for Human Rights, "for their encouragement to use their manuals, booklets and videos material and for their assistance in translating them into Arabic, Farsi, Kurdish, Turkish, and Urdu".

Through its front organisations, Scientology actively promotes the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, using material that is generally straightforward and factual. However, this also serves its own agenda – part of which is to get Scientology recognised as a religion when many regard it merely as a business selling expensive "self-improvement" courses.

Scientology also opposes psychiatry and associated medication, which it characterises as abusing human rights. It does this through yet another front organisation, the Citizens Commission on Human Rights. The patron and executive director of the Citizens Commission is Lady Margaret McNair – wife of Duncan McNair.

Bankrupt rights group 'received $13m via UAE'

21 August 2016: Details have begun to emerge about the Emirati funding of GNRD, the strange – and now bankrupt – human rights organisation accused of money-laundering.

In May last year Norwegian police raided GNRD's international headquarters in Stavanger, along with the home of its founder/president, Loai Deeb, on suspicion of money-laundering. Following the police raids GNRD's funding dried up and in July a Norwegian court declared it bankrupt for failing to pay employees' wages.

Legal documents released in Norway and reported last week by Stavanger Aftenbladet show that over a period of two-and-a half years more than $13 million was channelled to GNRD in Norway from "sponsors" in the United Arab Emirates.

It received more than $1.6 million via the UAE in 2013, almost $5 million in 2014 and more than $6.9 million in 2015. The figure for 2015 would probably have been far higher had the transfers not been curtailed in mid-year by the police investigation.

In 2013 and 2015 GNRD's largest donor was an Emirates-based company called Advance Security Technology FZE; in 2014 the main donor was Dubai-based Deeb Consulting FZF – in which GNRD founder Loai Deeb was sole proprietor. Another "significant sponsor" in 2015, according to Stavanger Aftenbladet, was MGS General Trading FZE, also based in the Emirates.

Other companies named as sponsors on GNRD's website were "Kaoud Law", "My Dream" and "Action Design" but little is known about them or what their contribution was. In August 2013, GNRD also received 100,000 euros from al-Mezmaah Studies and Research Center in Dubai.

The scale of the "donations" implies the Emirati companies must have been substantial businesses with profits running into the millions – but it's far from clear that they were.

Deeb's own Emirati company, Deeb Consulting, was set up in 2014 and, if his account is to be believed, it almost immediately became profitable enough to start funding GNRD (even though Deeb had no track record in business consultancy and was running it from afar, having never lived in Dubai).

Quoted in Stavanger Aftenbladet, Deeb explained this by saying "I have a large network in the Middle East, so it was possible for me to quickly establish a consultancy there" and "We made some good contracts early." However, he declined to give details, citing confidentiality and Emirati law.

Despite the apparently enormous and instant success of Deeb Consulting, a look at its website casts doubt on its level of expertise. As I demonstrated in a previous blog post, large parts of the website's content have been plagiarised from the websites of established consultancy firms.

Apart from being listed in several online business directories for the UAE, the other companies – Advance Security Technology and MGS General Trading – have no presence on the internet. A logo for Advance Security Technology was displayed on GNRD's website among its sponsors but a Google image search reveals no other usage of the logo except in connection with GNRD.

If these companies were not funding GNRD out of their profits, the most obvious alternative is that they were being used as conduits to disguise the true source of the money. It may be significant that all three companies are based in Emirati free zones, as indicated by the initials after their names. This would allow any income they received to be transferred abroad in full without deducting tax.

Asked why Emirati businesses would want to donate so much money to a human rights organisation in Norway, Deeb told Stavanger Aftenbladet it might seem a lot to Norwegians but for some businesses in the Emirates it is not so much: "They wanted to support the work of human rights with these funds." He added that he did not understand how support for such work could be considered money laundering. Both Deeb and GNRD (the Global Network for Rights and Development) deny the charges.

The money-laundering case has yet to come to court and Norwegian police remain tight-lipped about their investigation which is believed to involve transactions in multiple countries. However, the police have previously said they suspect the money involved is the "proceeds of crime".

In 2013, Deeb's personal income – which had been around $25,000 a year until 2012 – suddenly leapt to $600,000, raising questions about where the money was coming from.

During last year's raids, police seized gold jewellery valued at $220,000 from Deeb's home. According to the police it had been bought with cash. Deeb's wife claimed the jewellery belonged to her and in January she went to court seeking to have it returned. The court refused, saying it was "likely" that "at least the bulk" of the seized items had been purchased using the proceeds of criminal acts.

Norwegian media have also reported that in 2014 Deeb bought two properties in Norway for a total of 12.3 million kroner ($1.6 million) and paid for them in full without taking out a loan. In Jordan, he is said to have bought a villa for $534,000 – again, without taking out a loan.

Bankrupt rights group and an 'encyclopedia of terrorism'

17 September 2016: An article has appeared on three French-language websites defending GNRD, the strange (and now bankrupt) human rights organisation that Norwegian authorities have accused of money-laundering.

The article portrays GNRD as a brave non-western alternative to groups like Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International which has fallen victim to political machinations involving Qatar in particular. Not surprisingly, its author – René Naba, a French journalist of Lebanese origin – has connections with GNRD and two related organisations.

Naba, who was one of the speakers at a GNRD-organised conference on counter-terrorism last year, is a consultant for the International Institute for Peace Justice and Human Rights (IIPJHR) which was a partner with GNRD in many of its activities. He also belongs to a "consultative panel" for the Scandinavian Institute for Human Rights (SIHR), an organisation which was jointly established by GNRD's Palestinian-born founder-president, Loai Deeb, and Haytham Manna, a Syrian exile. Manna has also been a frequent participant in GNRD activities.

SIHR (an unfortunate acronym which means "witchcraft" in Arabic) and IIPJHR are both based in Geneva at 1 Rue Richard Wagner which was also the address of GNRD's Swiss branch before its bankruptcy.

Naba's article defending GNRD can be found on his own website, En Point de Mire, plus Libnanews where Naba is described as a "partner" and Madaniya, where Naba is the site's "director". A note on Madaniya's website says it receives "corporate support" from SIHR.

The money-laundering case, which has not yet come to court, arose from police raids on Deeb's home and GNRD's headquarters in Norway last May. The investigation is understood to have begun when large transfers of money from the UAE triggered an alert in the banking system but Deeb and GNRD, who deny the charges, say the case was instigated by the Qatari government.

In his article, Naba alleges various procedural irregularities relating to the police raids and says the documents seized included "a centerpiece of inestimable value" – a 1,000-page "encyclopedia" of terrorism which GNRD had been planning to publish, giving a country-by-country view of the "connections and funding of global jihadism".

Suppressing GNRD's encyclopedia was "undoubtedly the real reason for this muscular search", Naba says, adding:

"The chapters concerning Norway, Israel, Qatar and the United States are missing. And this might explain it. The same process had been used by the United States to intercept the report of the UN inspectors on chemical weapons, on their return from Baghdad to New York, during the media offensive leading up to the US invasion of Iraq in 2003."

Such conspiracy theories are based, of course, on an assumption that the Norwegian authorities had no genuine reason to investigate GNRD's finances. On that point, GNRD has made little effort to demonstrate that its funding came from legitimate sources beyond saying that it relied on business donors (one of whom was Deeb himself).

In the article Naba describes Deeb as a "fearless tycoon [brasseur d’affaires], consultant for oil firms and founder of a formidably dynamic NGO" who "arouses admiration and loathing for all his qualities".

If it's true that Deeb is a substantial businessman this would go a long way towards explaining GNRD's mysterious funding but Naba's article provides no evidence to support the claim and there are several reasons for doubting it.

Before founding GNRD in 2008, Deeb – a Norwegian citizen of Palestinian origin – did not appear to be particularly wealthy. According to Norwegian media reports he earned a living distributing newspapers and as an airport security guard, and his personal income was around $25,000 a year until 2013 when it suddenly leapt to $600,000.

Around the same time, GNRD began to receive very generous funding via the United Arab Emirates: more than $1.6 million via the UAE in 2013, almost $5 million in 2014 and more than $6.9 million in 2015. The figure for 2015 would probably have been far higher if payments had not been curtailed in mid-year by the Norwegian police investigation.

The donations came almost entirely from obscure companies registered in the UAE, at least one of which – Deeb Consulting, the main donor in 2014 – was owned entirely by Loai Deeb.

Deeb Consulting was set up in 2014 and, if Deeb's account is to be believed, it almost immediately became profitable enough to start funding GNRD on a grand scale. Quoted in Stavanger Aftenbladet last month, Deeb explained this by saying "I have a large network in the Middle East, so it was possible for me to quickly establish a consultancy there" and "We made some good contracts early." However, he declined to give details, citing confidentiality and Emirati law.

This apparently instant success is all the more remarkable since Deeb had no known expertise in business consultancy work and if, as Naba suggests, his clients were oil companies it is unclear why they would want to consult him. One question this raises is whether Deeb Consulting was a genuine business or merely a conduit for funds (see previous blog post).

One startling feature of Naba's article is that it refers to Deeb in French transliteration as "Lou'ay Dib Badeer". In a previous article, in May last year, Naba also called him "Loua'y Badeer". The "Badeer" name does not appear to have been used anywhere else – not even by Deeb himself, at least while living in Norway.

However, Badeer (or Badir) is apparently the name of Deeb's Palestinian clan. Naba writes:

"Anyone who knows a little about the Palestinian social fabric and the historic inter-clan solidarities would easily know that the Badeer the family divided its sympathies, like many Palestinian families, between the two charismatic leaders of the Palestinian national movement, Yasser Arafat, leader of Fatah, and George Habbash, head of the Marxist organisation PFLP (Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine)."

Naba's apparent purpose in mentioning this is to counter persistent claims that a hugely expensive conference on counter-terrorism organised by GNRD in Geneva last year had been funded by Mohammed Dahlan, the exiled former head of Palestinian "preventive security" in Gaza. The suggestion in Naba's article seems to be that traditional clan loyalties would have prevented Dahlan and Deeb from collaborating in such a way.

The Geneva conference was almost certainly the biggest and most expensive gathering organised by GNRD in its seven-year history and Deeb clearly attached great importance to it. Money appeared to be no object. It was attended by some 200 delegates from 67 countries and held in the five-star Hotel President Wilson on the shores of Lake Geneva where room prices start at around £250 a night.

British MEP Julie Ward was among those flown in for a panel discussion at the conference. GNRD paid for her £525 business class ticket from Manchester to Geneva via Brussels, and provided her with two nights' accommodation at the Wilson.

The main purpose of the conference was to present GNRD's solution to the problem of terrorism, in the form of a draft International Convention on Counter-Terrorism (full text here). Basically, GNRD's proposal was to set up an international body modelled on one of the UN's most ineffective institutions – the Human Rights Council – which would then compile a list of terrorist groups based on voting by member states rather than an assessment of evidence (see previous blog post for futher discussion of this).

Attendees at the conference were not given an opportunity to discuss the draft convention in open sessions but individual clauses from the draft were read out to them by a succession of female GNRD employees who had been given money to buy new clothes specially for the occasion.

Former director of bankrupt 'rights group' GNRD faces fraud charges

21 February 2017: A former director of GNRD, the strange "human rights" organisation that went bankrupt last year amid accusations of money-laundering, has been taken into custody on fraud charges in Austria.

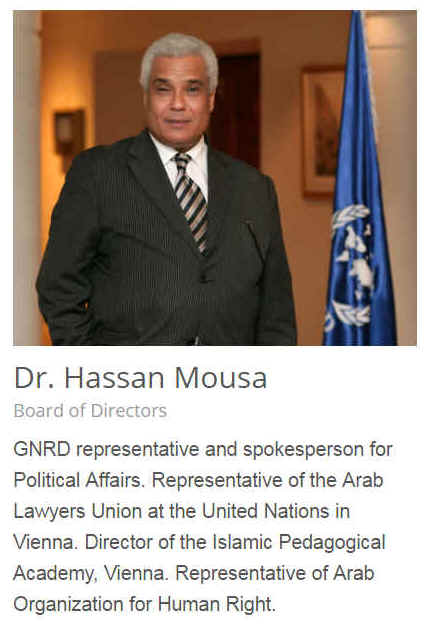

Hassan Moussa is suspected of diverting funds from an Islamic education centre in Vienna and is now in pre-trial detention, the Austrian newspaper Die Presse reports.

Moussa, 57, is a prominent figure in the Austrian Muslim community. He denies the charges and says he is the victim of "intrigue", according to his lawyer.

Moussa was chair of an organisation running the Austrian International Schools (AIS) – with classes from kindergarten to secondary level – which were subsidised from public funds. The schools became controversial partly because several of their alumni went on to become jihadists.

In 2015, the Swiss newspaper Neue Zürcher Zeitung published a detailed article about AIS headed Die Lieblingsschule der Fundamentalisten ("The favourite school of fundamentalists"). According to that report, all the girls wore hijab – even those who had not yet reached puberty – and fathers in Salafi garb were seen arriving with their children.

Moussa himself does not appear to have much interest in puritanical or political Islam. His office at AIS was extravagantly furnished and Neue Zürcher Zeitung describes him as having a fondness for "well-fitting suits" and "a predilection for expensive whisky". In 2013 he is also said to have joined a demonstration in Vienna against Egypt's Islamist president, Mohammed Morsi.

It appears that the school may have drifted in a fundamentalist direction under pressure from parents.

Last year, amid concerns about the nature of AIS, Vienna municipality withdrew its subsidies, forcing the schools into bankruptcy. However, a new organisation, known as "Oasis of the Child" sprang up at the same address and began operating nine kindergartens at various locations in the city. Die Presse says Moussa was not officially in charge of the new organisation but was "de facto" running it.

The main allegation against Moussa is that he transferred assets from the bankrupt AIS to Egypt, thus depriving creditors of their money.

Moussa was also a director of GNRD, the Global Network for Rights and Development, and its "spokesman for political affairs". Although funded almost entirely from mysterious sources in the United Arab Emirates, GNRD was based in Norway.

In May 2015, Norwegian police raided its offices and the home of its founder/president, Loai Deeb, as part of a $13 million money-laundering investigation. Following that, its funds dried up and in July 2016 GNRD too was declared bankrupt. GNRD denied money laundering and claimed the police investigation had been instigated by the government of Qatar.

GNRD had developed good relations with the Sisi regime in Egypt. In 2014 GNRD headed a "joint observer mission" for the presidential election which legitimised Sisi's seizure of power – and produced an enthusiastic report. "The Egyptian people have experienced a unique process toward democratic transition," it said, and commended them on "their achievements thus far towards a path to democracy".

Not surprisingly, GNRD was then chosen by the regime as an official observer for Egypt's parliamentary elections in 2015 and Mousa took charge of the operation. Turnout for the elections was low and although GNRD had promised to issue a report that would make "a vital contribution to this epoch-making democratic process" the report was never published.

Moussa took charge of GNRD mission observing elections in Egypt

New rights group rises from the ashes of GNRD

Blog post, 29 July 2017: A new human rights organisation which surfaced recently in Brussels has some uncanny connections with the scandal-ridden Global Network for Rights and Development (GNRD) which went bankrupt last year.

GNRD, headed by a man who previously ran a fake university, was funded with millions of dollars from mysterious sources in the United Arab Emirates and, not surprisingly, had an unusually favourable view of human rights in the UAE. Established in Norway in 2008, GNRD expanded rapidly and at one point it had more than 100 staff, with branch offices in Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, Sudan, Jordan and the UAE.

But in 2015 disaster struck. Norwegian police raided its headquarters as part of a $13 million money-laundering investigation. GNRD denied money-laundering, claiming the accusations against it had been instigated by Qatar.

A few months later, though, the funds dried up. Employees failed to receive their wages and in July last year a Norwegian court declared GNRD bankrupt.

The new organisation, known as the "Brussels International Center – Research and Human Rights" (or BIC for short), is based in the Belgian capital at 89 Avenue Louise which, by a remarkable coincidence, was previously the address of GNRD's branch office in Brussels.

Not only that. Of the seven people known to be working for BIC, all but one have some previous connection with GNRD and/or its network. Three of those now working at 89 Avenue Louise for BIC previously worked in the same building for GNRD.

Ramadan Abu Jazar was formerly a board member of GNRD and director of its operations in Brussels. He is now back at No 89 as head of research for BIC.

Brandon Locke, now a "consultant" for BIC, worked in Brussels as a policy researcher for GNRD between April 2014 and April 2016.

Fernando Inojosa Aguiar, from Brazil, was a "human rights policy researcher" for GNRD in Brussels between January 2015 and June 2016, according to his LinkedIn profile. He is now working in Brussels as BIC's Policy Officer for Africa.

Oddly, the biographical notes about these three on BIC's website make no mention of their previous work for GNRD.

A fourth ex-GNRD person, though not previously Brussels-based, is Miguel Cuñat. He was involved in various media activities for GNRD and served as a member of GNRD's observer mission for the presidential election in Egypt in 2014.

The head of BIC is Jean-François Fechino who formerly ran the Swiss-based International Institute for Peace Justice and Human Rights (IIPJHR). GNRD's Swiss branch had the same office address in Geneva as IIPJHR and the two organisations worked very closely together. They jointly organised numerous events in Europe and sent joint observer missions to Egypt for the presidential and parliamentary elections in 2014 and 2015.

Fechino left IIPJHR in June last year, according to his LinkedIn profile, and the organisation's Twitter and Facebook accounts show no further activity since then.

Another BIC person connected with IIPJHR, though not directly with GNRD, is Abdellah Bouhend, who spent four months working for IIPJHR last year.

The seventh person working for BIC is project manager Kathryn (Kate) Jackson who has no known connection with GNRD or IIPJHR.

The exact roles of Bouhend and Cuñat at BIC are unclear but both are listed as BIC representatives – along with Fechino, Abu-Jazar, Inojosa Aguiar and Jackson – in the EU's register of lobbying organisations. This means they are accredited for access to the European Parliament's premises.

At one point GNRD had as many as 15 staff with European Parliament accreditation and it organised several meetings hosted jointly with MEPs.

Mystery of an anonymous author and the Black Book on Qatar

Blog post, 26 November 2017: An anonymously-written book produced by a seemingly fictitious organisation and promoted by a group of French-language websites appears to be the latest weapon in the Saudi-Emirati propaganda war with Qatar.

"Qatar: Le Livre Noir" (Qatar: The Black Book) is said to have been compiled by researchers from the Centre Euro Arabe pour Combattre l'Extrémisme (CEACE) but internet searches have so far failed to locate any details about the organisation or any mention of it except in connection with the mysterious Black Book.

The Black Book itself says CEACE was formed in Paris on 21 April this year, at a meeting of five human rights NGOs. The NGOs are not named, and the book says CEACE has decided "to postpone to a later date the disclosure of the identity of the organisations participating in the project". It says CEACE has also decided to maintain the anonymity of its researchers "for obvious reasons of security".

The Black Book was initially posted online in Arabic under the title "Qatar: Al-Kitaab al-Aswad". A report in the Emirati newspaper al-Bayan on September 27 described it as "an extensive analysis of Qatar's role in supporting terrorism". Al-Khaleej, another Emirati paper, also published an article about it in September. The Saudi newspaper al-Riyadh had two reports (here and here) in October.

GNRD connection

During November several inter-linked French-language websites have been publishing extracts from the book's French edition or articles about it written by journalist René Naba. They include Naba's personal website, En Point de Mire, plus Libnanews where Naba is described as a "partner" and Madaniya, where Naba is the site's "director".

Last year the same three websites published articles by Naba defending the Global Network for Rights and Development (GNRD), a strange organisation funded almost entirely via the UAE which closed down in July 2016.

Naba had several connections with GNRD. He was one of the speakers at a GNRD-organised conference on counter-terrorism in 2015 and is a consultant at the International Institute for Peace Justice and Human Rights (IIPJHR) which was a partner with GNRD in many of its activities. He also belongs to a "consultative panel" for the Scandinavian Institute for Human Rights (SIHR), an organisation which was jointly established by GNRD's founder-president, Loai Deeb, and Haytham Manna, a Syrian exile.

SIHR and IIPJHR are both based in Geneva at 1 Rue Richard Wagner which was also the address of GNRD's Swiss branch before it closed.

A surprise in Chapter 7

Skimming through the text of the Black Book, I was surprised and amused on reaching Chapter 7 to find myself and my website portrayed as the leading examples of Qatari soft power. The book's anonymous author seems confused about al-bab's web address, variously referring to it as albab.net, al-bab.net and al-bab.com, but maintains that it is "the best embodiment" of Qatar's media strategy:

Le site anglais albab.net, pro Qatar, incarnera le mieux cette politique, pointant les intrusions hostiles sur les sites du Qatar, au moment où Doha réussissait à acquérir auprès de hackers un important lot de messages (mail) appartenant à des diplomates et responsables gouvernementaux des 4 pays arabes en guerre contre le Qatar (Arabie saoudite, Bahreïn, Égypte, Koweït).

The book goes on to say that after setting up al-bab as a website about Yemen I went to Qatar in search of funding and, following my stay in Doha, I expanded the site to include the other Arab countries. It seems to be implying that the expansion was a result of Qatari funding:

Il se rend au Qatar en quête d'un financement pour son site dédié, dans un premier temps au Yémen, qu'il étendra à l'ensemble du Monde arabe après son séjour à Doha.

That is untrue. I don't remember exactly when the expansion happened but archived web pages show it was sometime between April 1999 and February 2000. At that point, though, I had never been to Qatar. My first visit was in 2003 and I went again in 2006. Those have been my only visits to Qatar. On both occasions I was reporting for the Guardian and the Guardian covered the full cost.

For readers unfamiliar with al-bab, I run the site myself. It doesn't employ anyone and has never had external funding, though it does generate a small income from Google ads and book sales through Amazon. The website is critical of all Arab regimes, including Qatar's (here, for example).

In 2014, according to the Black Book, I was instructed by Qatari intelligence to launch a campaign "against the institutions of the UAE", with supporting information provided by activists from Hamas and the Muslim Brotherhood:

En 2014, sur instructions des services des renseignements du Qatar, il a mené campagne contre les institutions des Émirats Arabes Unis et contre ceux qui étaient en accord avec la politique hostile d'Abou Dhabi à l'encontre des Frères Musulmans et du mouvement salafiste.

Pour ce faire, il a été en contact avec des activistes du Hamas et des Frères Musulmans chargés de alimenter en informations sa campagne, tels Azzam Tamimi, Directeur exécutif de la Chaîne «Al Hiwar» de Londres, Waddah Khanfar, le frère de ce dernier, chef du Hamas à Jenin (Cisjordanie).

Again, that is untrue and the book provides no evidence to support its claims. The talk of me conducting "a campaign" seems to be alluding to my lengthy investigation of GNRD which began in 2014. Nobody told me to do it. My interest in GNRD was triggered by the discovery that its founder had previously run a fake university and, the more I looked into it, the weirder the organisation became. The resulting articles relied on open sources, as readers can see. I had no need to contact anyone from Hamas or the Muslim Brotherhood about it – and I didn't do so.

In 2015, GNRD was raided by police amid suspicions about its funding. After that, its funds dried up and in 2016 it was declared bankrupt for failing to pay its employees' wages. The Black Book doesn't explain why it closed but says I toppled GNRD while working "in close collaboration" with the Qatari embassy in Norway, the pro-Israel lobby and Qatari intelligence:

Brian Whiteker [sic] a été en outre chargé de mener campagne contre GNRD. En étroite collaboration avec l'ambassade du Qatar en Norvège, le lobby pro-israélien du pays et les services de renseignements du Qatar, Whitker [sic] a réussi à torpiller cette organisation non gouvernementale ...

That's also untrue but apparently my success in toppling GNRD meant I was "naturally destined to occupy a place of choice within the Qatar lobby". For good measure, the book adds that I also maintain contacts with British intelligence services which "turn a blind eye to the considerable sums" that I allegedly receive from Qatar:

Le propagandiste anglais du Qatar passe pour entretenir des contacts suivis avec les services de renseignements britanniques, qui ferment l’œil sur les sommes considérables qu'il reçoit du Qatar.

Another UAE-linked rights group vanishes in a trail of debt

Blog post, 1 December 2017: A second human rights organisation run by Loai Deeb – founder of the Emirati-linked Global Network for Rights and Development (GNRD) which went bankrupt last year – has run into financial trouble. The International Institute of Peace Justice and Human Rights (IIPJHR) has vanished from its Geneva office, pursued by creditors seeking to recover more than $30,000 in debts.

Palestinian-born Deeb, who previously ran a fake university from his home in Norway, established GNRD in 2008. Despite being one of the world's strangest human rights organisations it acquired consultative status at the United Nations, gained official recognition from the EU, established partnerships with several real universities and was registered for lobbying purposes at the European Parliament in Brussels.

In 2015, however, police raided GNRD's Norwegian headquarters as part of a $13 million money-laundering investigation and a year later it was declared bankrupt after failing to pay its employees' salaries. The money-laundering case has not yet been determined by the courts. GNRD and Deeb deny the charges and claim the accusations against them were instigated by the government of Qatar.

Before GNRD shut down it worked very closely with Swiss-based IIPJHR. The two organisations held numerous events together and sent joint observer missions to elections in Tunisia and Egypt. GNRD's Swiss branch office used the same address in Geneva as IIPJHR. Like GNRD, IIPJHR has consultative status at the United Nations.

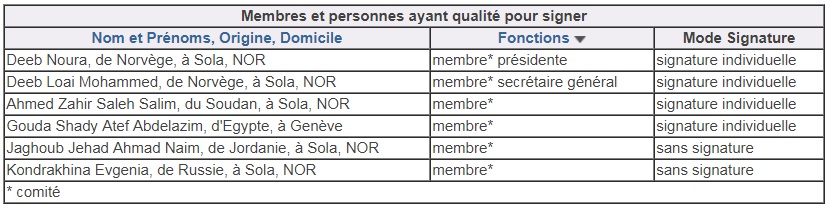

Official registration documents show GNRD founder Loai Deeb is currently secretary-general of IIPJHR and his wife, Noura, is its president. Another of its board members is Evgenia Kondrakhina, a Russian who was formerly GNRD's chief executive:

The director of IIPJHR, until June last year, was Jean-François Fechino. He now heads the"Brussels International Center – Research and Human Rights", a new organisation operating from an address formerly used by GNRD for its Brussels branch office. Most of the new organisation's staff also previously worked for GNRD.

Emirati connections

GNRD appears to have been one element in the propaganda war between the UAE and Qatar which has been running, off and on, for several years. In the course of this feud both countries have resorted to using front organisations and have also exploited the fruits of computer hacking. (For details of recent developments in that area, see The Quarrel with Qatar).

GNRD had an unusually favourable view of human rights in the UAE and at one point produced a worldwide human rights league table which gave the UAE a laughably high ranking. In 2014 Qatar arrested two researchers who had been sent by GNRD to investigate the abuse of migrant workers. They were eventually released without charge.

At its peak, GNRD employed dozens of staff, had offices in Norway, Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, Sudan, Jordan and the UAE – and an income of several million dollars a year. According to the Norwegian authorities almost all the income it received came from sources in the UAE.

GNRD has always denied being funded by the UAE government but evidence has now emerged of a direct connection between IIPJHR and two Emirati citizens.

IIPJHR was established in 2010 and Swiss official records show Loai Deeb took over as its secretary-general in March 2014. At the same time Noura Deeb became its president and Abu Jazar Ramadan, head of GNRD's Brussels office, became vice-president.

However, in May 2016 they all stepped down and two Emiratis living in Dubai took control. The records name them as Shamsa Majid Khalfan Qaraiban, who became president, and Yousuf Ali Ahmad Bin Zayed Alfalasi, who became vice-president.

The Emiratis remained in charge for precisely 14 days before handing IIPJHR back to Noura and Loai Deeb, as a subsequent document shows. There is nothing in the documents to explain the reason for this short-lived transfer.

Connections with the 'Black Book'

IIPJHR appears to be no longer functioning – its website and Twitter feed haven't been updated for well over a year – but there are several connections between IIPJHR, GNRD and a "Black Book" about Qatar which was recently published anonymously online.

The book purports to have been compiled by researchers from the "Centre Euro Arabe pour Combattre l'Extrémisme" (CEACE) – a previously unkown organisation which was allegedly formed in April this year by five unnamed human rights NGOs. The book adds that the researchers who compiled it are also remaining anonymous "for obvious reasons of security".

A skim through the book shows that these researchers – whoever they might be – have relied heavily on articles by a French journalist, René Naba, written for his personal website or published by Madaniya, a website where Naba is described as director.

Since the book was published, Naba has been very active in promoting it online (see previous blog post). Loai Deeb has also tweeted about the book:

Naba was one of the speakers at a GNRD-organised conference on counter-terrorism in 2015 and is (or was) a consultant at IIPJHR. He also belongs to a "consultative panel" for the Scandinavian Institute for Human Rights (SIHR), an organisation which was jointly established by Loai Deeb, and Haytham Manna, a Syrian exile.

Last year Naba wrote an article defending GNRD in which he claimed the purpose of the Norwegian police raids had been to suppress valuable research into terrorism.

He wrote that documents seized by police included "a centerpiece of inestimable value" – a 1,000-page "encyclopedia" of terrorism which GNRD had been planning to publish, giving a country-by-country view of the "connections and funding of global jihadism".

Suppressing GNRD's encyclopedia of terrorism was "undoubtedly the real reason for this muscular search", he said.

Human rights chief embezzled $1 million to cover losses on internet gambling, police say

Blog post, 7 January 2018: The head of an international human-rights-and-development organisation siphoned off more than $1 million of its funds to cover his gambling debts, police and bankruptcy investigators believe.

Palestinian-born Loai Deeb founded the Global Network for Rights and Development (GNRD) in 2008, while also running a fake university from his home. Based in Norway but funded almost entirely via the United Arab Emirates, GNRD expanded rapidly, opening branch offices in Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, Sudan, Jordan and the UAE. It also gained official recognition from the UN, the EU and the African Union and acted as an official observer for elections in several Arab and African countries.

In 2015, Norwegian police raided GNRD's headquarters and Deeb's home on suspicion of money-laundering. That case has still not come to court and Deeb denies the charges, claiming the police action was part of a vendetta by the government of Qatar.

Following the raids GNRD's funding dried up and in 2016 it was declared bankrupt after failing to pay employees' wages for several months.

Deeb, however, appeared to prosper while running GNRD. In 2013 his personal income – which had been around $25,000 a year until 2012 – suddenly leapt to $600,000, raising questions about where the money was coming from. In 2014 he bought two properties in Norway for a total of 12.3 million kroner ($1.6 million) and paid for them in full without taking out a loan. In Jordan he bought a $534,000 villa – again without needing to borrow.

During the 2015 raids, police confiscated $220,000-worth of gold jewellery from Deeb's home. A court later refused to return it, saying that "at least the bulk" of the seized items were "likely" to have been purchased using the proceeds of criminal acts.

Online gambling losses

It has since been alleged that Deeb was also gambling heavily with GNRD's money. In September, Norwegian broadcaster NRK reported that he had run up losses of more than 10 million kroner ($1.2 million) with Betsson and NordicBet – two online gaming firms. It quoted an unnamed former employee of one of the gaming firms as saying Deeb "was one of our top customers for a while and could play for millions in a matter of months".

NRK said it had gained access to multiple bank statements showing transfers from GNRD's account to Swiftvoucher, a payment system used by gaming companies. Swiftvoucher advertised its services as a way of making payments online "without having to reveal your confidential card or bank account details".

Deeb denies embezzlement and appears to be claiming that GNRD used Swiftvoucher for legitimate international payments.

Disguised payments

However, a report last week by Hans Petter Aass for Stavanger Aftenblad gave new details of how GNRD's payments to online gambling firms were allegedly disguised.

Among documents seized during the 2015 police raids was a purported contract with a South African water company dated 12 January 2013. Under the contract, GNRD was supposed to sponsor water projects carried out by the South African firm in Chad, Congo, Cameroon and the Central African Republic.

According to Stavanger Aftenblad, this contract was a fake. The South African company says it has no knowledge of any such agreement with GNRD and the person who apparently signed it on behalf of the firm has never worked there.

Between February 2013 and April 2014, supposedly in connection with this contract, GNRD made no fewer than 860 payments. The paper says these payments "largely coincide" with Deeb's gambling activity and that police believe the contract document was intended to conceal it.

Stavanger Aftenblad quotes Deeb's lawyer as saying: "Such an alleged counterfeit is completely unknown to my client."

Meanwhile Bengt Eriksen, the chief accountant dealing with GNRD's bankruptcy, has identified further irregularities in the organisation's finances besides the online gambling. In an official report last month he also highlighted loans from GNRD to Deeb made without a formal agreement, private travel expenses charged to GNRD and undocumented payments to Deeb's account, plus coverage of his private rent and his personal lawyer's expenses.

Legal documents released in Norway show that GNRD's funding via the UAE amounted to more than $1.6 million in 2013, almost $5 million in 2014 and more than $6.9 million in 2015. The figure for 2015 would probably have been far higher had the transfers not been curtailed in mid-year by the police investigation.

In its heyday, GNRD appeared to be a free-spending organisation. For an especially lavish conference on terrorism, held in Geneva in 2015, female staff were allowed to buy new outfits on expenses.

Deeb and GNRD also purchased millions of fake followers on social media and regularly paid for their tweets to be retweeted by thousands of bogus accounts. The same bogus accounts were used to spread defamatory tweets about al-bab when it investigated GNRD's affairs.

The big question yet to be answered is who was really funding GNRD, and why they handed over so much money without, apparently, taking much interest in how it was used.

In 2013 and 2015 GNRD's largest donor was an Emirates-based company called Advance Security Technology FZE; in 2014 the main donor was Dubai-based Deeb Consulting FZF – in which GNRD founder Loai Deeb was sole proprietor. Another "significant sponsor" in 2015, according to Norwegian media, was MGS General Trading FZE, also based in the Emirates.

Deeb has previously claimed these were successful companies, generously donating profits to GNRD. But so far there is no evidence that any of them were substantial businesses and it seems more likely that funds were simply being channelled through them in order to disguise the true sources.

Advance Security Technology and MGS General Trading – have no presence on the internet apart from being listed in some online business directories.

Deeb Consulting appears to have had little or no expertise in consulting and may or may not have been a real business. It did have its own website (since deleted) but its content had been plagiarised from the websites of established consulting firms.

Police say UAE is not cooperating with money-laundering investigation

Blog post, 13 May 2018: A lack of cooperation from the United Arab Emirates has been hampering investigations into a multi-million dollar money-laundering case, according to Norwegian authorities.

It is almost three years since police raided the headquarters of the Norway-based Global Network for Rights and Development (GNRD) and the home of its founder, Loai Deeb, on suspicion of money-laundering.

Norwegian police say they sent a request to the Emirati authorities for help with the investigation in August 2016 and are still waiting for an answer. They also say they have not been granted an opportunity to question people in the Emirates who may have been involved in suspicious money transfers.

In its human rights work GNRD promoted an unusually favourable view of the situation in the UAE and, according to investigators, almost all its funding came via the UAE. Between 2013 and 2015 a series of Emirates-registered companies (which appear not have been genuine businesses) received large amounts of money from unidentified sources and then transferred it to GNRD – a total of around $13 million.

At its peak, GNRD had branch offices in several countries and about 140 employees worldwide. It had consultative status at the United Nations and was registered for lobbying purposes at the European Parliament in Brussels. It had a cooperation agreement with the African Union and acted as an official observer for elections in several Arab and African countries.

Following the police raids GNRD's funding dried up. It stopped paying its employees and was eventually declared bankrupt.

Investigations in other countries

Despite the difficulties in getting information from the UAE, investigations relating to GNRD's finances have been taking place in at least four other countries – Switzerland, Belgium, Austria and Britain – according to the Norwegian newspaper Stavanger Aftenbladet.

In Switzerland, the Geneva public prosecutor's office says it is "conducting criminal proceedings" involving GNRD and another organisation, the Scandinavian Institute for Human Rights (SIHR) which was founded jointly by Deeb and Haytham Manna, a Syrian exile who is a close associate of Deeb. According to the prosecutor, both Deeb and Manna "appear in such proceedings".

GNRD and SIHR shared an office address in Geneva and Manna attended and spoke at various GNRD events. In a telephone interview with Aftenbladet, Manna described the Swiss investigation as "fake news" and said he had not been contacted by the police.

In Austria, investigations have focused on Hassan Moussa, who was a board member of GNRD for several years before it went bankrupt. Moussa is currently facing fraud charges in connection with an organisation called Austrian International Schools which he chaired. He denies the charges and says he is the victim of "intrigue", according to his lawyer.

GNRD was very active in Brussels where it developed relationships with several members of the European Parliament. Aftenbladet reports that Belgian police have interviewed a former GNRD employee there and have also compiled almost 1,000 pages of investigation documents. Deeb's lawyer told the newspaper most of the documents were about Belgian banks and "as far as I can see, there is no material found in the Belgian investigation that is to my client's disadvantage".

Police enquiries in Britain relate to payments allegedly made by Deeb in connection with online gambling.

Several recent reports in Norwegian media have discussed how the legal case is likely to proceed. The authorities have dropped the money-laundering charges against GNRD on the grounds that the organisation is now bankrupt, though they are apparently continuing to pursue similar charges against Deeb personally.

However, in the absence of cooperation from the UAE, prosecutors say their focus has shifted to "criminal offences committed in Norway".

As yet there has been no formal announcement of what the additional charges against Deeb will be but Norwegian media reports say they are likely to include fraud, document forgery and tax evasion.

On May 3, Deeb posted a press release on Facebook saying the charges against GNRD and himself had been "dismissed", though it went on to say he had been "charged with embezzlement of funds from GNRD as well as some completely insignificant relationships". It added: "None of the charges are associated with the charge of money laundering. Deeb claims he didn't commit a crime."

Compensation claim

Deeb blames the police action for GNRD's bankruptcy and in a further Facebook post on May 8 he said its lawyers are preparing a compensation claim against Økokrim, the Norwegian financial police. His post invited former employees to join the compensation case by signing a form which would give GNRD's lawyers power to act on their behalf.

One reported claimant is Joseph Chilengi who was GNRD's "High Commissioner for Africa". He says he is owed about 750,000 kroner ($94,000), mainly in unpaid salary.

Chilengi is currently Zambia's ambassador to Turkey. At the time of his GNRD appointment he was chair of the general assembly of the African Union's Economic, Social and Cultural Council (ECOSOCC). In 2013, GNRD signed a memorandum of understanding with the African Union "to facilitate the development and integration agenda" of the AU and "explore opportunities for cooperation and non-exclusive partnership". In 2015, Chilengi flew to Spain at GNRD's invitation to take part in an Africa Day debate.

Former head of rights group GNRD faces million-dollar embezzlement charge

Blog post, 17 May 2018: Loai Deeb, former head of the Global Network for Rights and Development (GNRD), has been formally charged with a series of financial crimes which include embezzling more than a million dollars from the organisation that he founded. He is said to have disguised his embezzlement through a fake contract to provide drinking water for refugees in Africa.

GNRD itself, which was based in Norway but funded almost entirely from mystery sources in the United Arab Emirates, was declared bankrupt in 2016 (background here).

Deeb, who faces trial in Norway, denies committing any crimes. The charges against him are summarised below:

1. Between February 2013 and August 2014 he misused 10,090,903 kroner ($1,247,000) of GNRD's funds for internet gambling.

2. Under a fake contract with a company called Water and Sanitation Services the missing money was falsely accounted for as expenditure on safe drinking water for refugee camps in Africa.

3. He created fictional employment for an Iranian man which allowed him to obtain a residence permit.

4. In connection with the residence permit he gave the Norwegian Directorate of Immigration (UDI) an incorrect explanation of the Iranian man's working relationship with GNRD.

5. Use of forged documents with unlawful intent:

a) In May 2014 he submitted to GNRD's accountants a fake sponsorship agreement between GNRD and a company called Lana Interiors. The document was purportedly signed by GNRD's vice-president Abozer Mohamed, even though he had neither signed it nor given his consent that the signature could be used.

b) In June 2014 he submitted the fake contract with Water and Sanitation Services to GNRD's accountants, which resulted in false accounts being presented to the UN in connection with GNRD's application for consultative status with ECOSOC.

c) Between October 2014 and February 2015 he submitted false accounts for GNRD's Jordanian office in connection with GNRD's application for consultative status with ECOSOC.

6. On or before June 8, 2017, he submitted false documents to the tax office. These were a confirmation from the Papyrus Travel of delivered services amounting to $171,485 and six invoices totalling $1,112,371 from the fictitious travel company EVKTRIP.

7. Between June 2013 to March 2015 he imported into Norway gold or jewellery worth approximately 800,000 kroner ($100,000) without declaring it to customs.

Fraud, fakery and human rights: the end of a strange organisation

|

Blog post, 9 November, 2018: In 2014 two human rights researchers from Britain went missing in Qatar. They had gone to investigate the conditions of migrants working in the Gulf state and it turned out that the authorities, displeased by the researchers' activities, had arrested them. International media took up the case and nine days later the men were released without charge.

That might have been the end of the story except for one small fact. The researchers were not employed by one of the well-known human rights organisations but by an organisation that hardly anyone had heard of – the Global Network for Rights and Development (GNRD).

GNRD was based in Norway, had plenty of funds and, according to its website, prided itself on using "out-of-the-ordinary" approaches to humanitarian issues. Just how out-of-the-ordinary its methods were started to become clear in 2015 when police raided its headquarters on suspicion of laundering millions of dollars. GNRD has since gone bankrupt and, following a trial in September, its founder-president has now been convicted of fraud and forgery.

Emirati connections

The ill-treatment of migrant workers had long been a scandal in the Arab Gulf states, and Qatar was no exception. But GNRD's specific focus on abuses by Qatar seemed to be motivated by politics. At the time, Qatar and its Gulf neighbour, the United Arab Emirates, were engaged in one of their periodic spats and despite GNRD's claims of being "neutral and impartial" it had clear Emirati sympathies.

A search of its website revealed several enthusiastic reports about the UAE's human rights "achievements" and an international human rights league table published by GNRD showed the Emirates in 13th position worldwide, just one place behind the UK and far ahead of any other Arab country. Qatar, meanwhile, was ranked in 85th position.

There were also some troubling questions about GNRD's founder-president, Loai Deeb. Before setting up his human rights organisation in 2008, Palestinian-born Deeb – who had acquired citizenship in Norway – was head of the "Scandinavian University", a fake institution based at his home in Stavanger which had eventually closed down under threats of legal action by the Norwegian authorities.

Deeb himself pretended to have a doctorate in international law from Oxford University and insisted on being known as "Doctor Deeb".

Online harassment

Intrigued by Deeb's background and GNRD's apparent connection with the UAE, I began monitoring its activities in a series of blog posts. GNRD responded by accusing me of "criminal harassment" and urging "respected institutions" to take no notice of what I was writing. It said in a press release:

"After carefully examining all the claims made by Mr Brian Whitaker in his articles, GNRD have found that the allegations are often false and misleading and therefore GNRD is in the process of opening a legal case."

I never heard from GNRD's lawyers but shortly afterwards there were repeated attempts to hack my social media accounts and several fake accounts were created using my name. Over a period of several weeks, hundreds of automated Twitter bots also posted defamatory tweets about me. Among other things, they falsely accused me of being paid by the Qatari government and claimed I had been expelled from Yemen for a sexual offence. Interestingly, the same bots posting these tweets were also being used to promote the activities of Loai Deeb.

Later, GNRD organised a demonstration outside the UN building in Geneva where a statement was read out denouncing my blog posts (see video below).

Gaining acceptance

At its peak, GNRD had more than 100 staff, with branch offices in Belgium, Switzerland, Spain, Sudan, Jordan and the UAE as well as its headquarters in Norway.

The alarming thing about this was how readily it became accepted as a normal humanitarian organisation when a few rudimentary checks would have shown it was anything but normal. Regardless of its peculiarities, GNRD had been granted consultative status at the United Nations, signed a cooperation agreement with the African Union and acted as an official observer for elections in several Arab and African countries.

At one point GNRD had no fewer than 15 staff accredited by the European Parliament in Brussels for lobbying purposes and it organised several meetings hosted jointly with MEPs. It also struck collaboration agreements with universities in Norway and Spain and, rather bizarrely, established a relationship with the Church of Scientology.

Posts on GNRD's website gave the impression of a lot of activity, perhaps to show its mystery backers they were getting something for their money, but on a closer look there was little of substance. The website documented numerous meetings, almost always held in conjunction with some another organisation. Its reports usually ended by expressing a hope that the two organisations would work together again in the future, and this looked like a deliberate strategy for GNRD to gain credibility through association.

Big ambitions

By 2014 there were signs that GNRD had big ambitions but several attempts to engage with issues more directly and proactively resulted in failure – as with the hapless researchers sent to Qatar.

In May 2014, for instance, it dispatched a five-person mission to the Kurdish-held area of northern Syria which returned home empty-handed, having been unable to reach its intended destination.

A few months later, with Yemen on the brink of civil war, GNRD flew prominent Yemenis to a conference in Brussels which Deeb hailed as "a real opportunity to achieve an all-inclusive national reconciliation". However, the conference achieved nothing apart from issuing a declaration described by one Yemeni political analyst as "worthless in terms of its substance and content".

Early in 2015, GNRD attempted to tackle the problem of terrorism with a two-day conference at one of the most luxurious hotels in Geneva. Some 200 delegates from 67 countries were said to have attended and a list of "VIP guests and speakers" showed that a number of genuine counterterrorism experts were among them.

The main purpose of this hugely expensive event was to promote GNRD's draft of an "International Convention on Counterterrorism". The proposed convention was clearly unworkable but extracts from the document were read out to the conference by a succession female GNRD employees who had been allowed to buy new clothes on expenses specially for the occasion (see video below):

Questions of funding

Exactly who was paying for GNRD's activities is still a mystery but it's now known that almost all its funding came via the UAE – a total of more than $13 million between 2013 and 2015.

Deeb claimed it was "sponsorship" money from successful businesses he had established in the Emirates. One of these companies, Deeb Consulting which he supposedly ran with his brother, was GNRD's main donor during 2014. However, there are plenty of signs that Deeb Consulting was not a real business. It appears that money was simply being channelled through shell companies in order to disguise the true sources of GNRD's funding.

The large transfers of money eventually triggered an alert in the international banking system and in May 2015 Norwegian police raided GNRD's headquarters and Deeb's home on suspicion of money-laundering. Following the police raids GNRD's funding dried up, salaries went unpaid and a few months later the organisation was declared bankrupt.

Deeb's crimes

The money-laundering investigation didn't get very far – largely because the UAE failed to cooperate. Norwegian police say they sent a request to the Emirati authorities for help with the investigation but never received an answer and were given no opportunity to question people in the Emirates who may have been involved in suspicious transfers.

However, in the course of their money-laundering investigation the police uncovered other crimes for which Deeb has now been convicted. These are set out in detail in a written judgment issued by the court.

Considering Deeb's previous incarnation as head of the fake "Scandinavian University", it's not surprising that most of the charges against him involved some form of fakery. Documents uncovered by the Norwegian police, for example, included a series of false invoices for travel expenses.

Part of this deception was connected with GNRD's efforts to gain official recognition from ECOSOC, the UN's Economic and Social Council. An initial application for consultative status was refused on the grounds that GNRD's accounts were not in order. Some forged paperwork solved the accounting problem and a further application, in 2014, was granted. Besides enhancing GNRD's credibility, this allowed it to take part in the activities of the UN Human Rights Council and to hold meetings on UN premises in Geneva.

Among the documents that helped secure ECOSOC's recognition was a set of accounts for GNRD's Jordan office, purportedly verified by an auditing firm which turned out to have been unregistered and had a phone number that didn't work. In its written judgment, the Norwegian court concluded that the audit report was false and had been produced by Deeb and his staff to mislead the UN in connection with the ECOSOC application.

Another document presented in support of the ECOSOC application was a fake contract with a South African company, Water and Sanitation Services. This was supposedly an agreement whereby GNRD would sponsor water projects carried out by the firm in Chad, Congo, Cameroon and the Central African Republic – but the firm denies all knowledge.

Later on, the fake water contract also provided cover for Deeb's online gambling. He was a heavy gambler and according to court documents used at least $1.2 million of GNRD's funds (as well as his own money) for this activity. Payments to gaming companies were disguised in GNRD's accounts as payments for African water projects.

As a result of the police raid on his home, Deeb was also found to have imported large amounts of gold without declaring it to customs. A safe in his house contained three kilograms of gold jewellery with a precious-metal value of about $120,000. On a separate charge he was convicted of giving false information to Norwegian immigration authorities in connection with a residence permit for an Iranian who was purportedly working for GNRD.

Deeb has been sentenced to four-and-a-half years in jail, though he is currently free pending a possible appeal.

What was it about?

Despite the lengthy police investigation, Deeb's intentions in creating GNRD are still a puzzle. Although he founded the organisation in 2008, its website showed no significant activity until 2013 when large sums of money began arriving via the Emirates.

Deeb's own financial situation changed spectacularly around the same time. His personal income in Norway, which had been around $25,000 a year until 2012, suddenly leapt to $600,000 in 2013. In 2014 he bought two properties in Norway for a total value of 12.3 million kroner ($1.6 million) and paid for them in full without taking out a mortgage.

Money-making aside, Deeb was clearly on some kind of ego trip. He ran GNRD in the style of a Middle Eastern autocrat and maximised the opportunities for self-promotion. On social media he described himself as a "public figure" and, although little known, appeared to be enormously popular. His Facebook page had 1.2 million "likes" and his Twitter account had 1.46 million followers – presumably paid for. Norwegian media pointed out that if these figures were true Deeb would be the most popular person in the country, with more online fans than all the government ministers and members of parliament combined.

GNRD and the Emirates

One big unanswered question is the exact nature of GNRD's relationship with the Emirates. Although no evidence has emerged of direct government funding, the UAE's non-cooperation in the money-laundering case can be viewed as a sign of GNRD's favoured status. It was also allowed to maintain a branch office in the Emirates where independent civil society organisations and international NGOs are not normally welcome.

Although most of GNRD's funds came via the UAE from untraceable sources, a document dated August 2103 shows a bank transfer of 100,000 euros to GNRD from al-Mezmaah Studies and Research Center in Dubai. Al-Mezmaah describes itself as "an independent centre established by Dr Salem Humaid with the aim of concentrating on the regional affairs of the United Arab Emirates and also its repercussion at the Arab and international level and all that which exalt [sic] the name of the United Arab Emirates".

Al-Mezmaah engages in a wide range of activities but has been especially active campaigning against Qatar, Iran and the Muslim Brotherhood, as can be seen from the articles on its website.

Salem Humaid, the founder of al-Mezmaah, has held various government posts in Dubai – most notably with the Dubai Culture and Arts Authority. He has also written occasionally for the Emirati newspaper, The National. One of his articles for The National attacked Human Rights Watch, suggesting it was "little more than a mouthpiece for the Muslim Brotherhood's international organisation".

GNRD and Egypt

Beyond the UAE, though, GNRD had several other political connections. In 2014 it was one of three obscure organisations appointed as international observers for the presidential election which legitimised General Sisi's seizure of power. The observer mission later produced an enthusiastic report which said the Egyptian people had "experienced a unique process toward democratic transition" and complimented them on "their achievements thus far towards a path to democracy".

One senior member of GNRD's observer mission for the presidential election was its grandly-titled "High Commissioner for Europe", the late Anne-Marie Lizin, a Belgian politician who had been convicted of electoral malpractice and banned from holding public office.

The following year GNRD was appointed again to observe Egypt's parliamentary elections. It sent a large observer team and issued a preliminary report on "this epoch-making democratic process" but a promised "comprehensive final report" on the elections never materialised. By then, though, GNRD was facing serious internal problems as a result of the Norwegian police investigation.

GNRD and the Kurds

During the conflict in Syria, GNRD developed a relationship with the Kurdish Democratic Union Party (PYD). This appears to have come about through Deeb's connection with Haytham Manna, a Syrian leftist and secularist based in Paris. Deeb and Manna had previously worked together in an organisation called the International Coalition Against War Criminals (ICAWC) which in 2009 attempted to have three Israeli politicians and seven military commanders prosecuted for war crimes.

Manna, who was a speaker at several GNRD events, later became a founder of the Syrian National Coordination Body for Democratic Change in which Kurdish Syrians were represented by the PYD.

In 2013 GNRD held a conference in Brussels under the title "Against Dictatorship and Foreign Intervention in Syria". The four main speakers were Deeb and Lizin from GNRD, plus Manna and Khaled Issa, the PYD's representative in France. A report of the conference posted on GNRD's website was among various items deleted when Norwegian media began taking an interest in its activities.

The PYD helped arrange two GNRD fact-finding missions, including the one mentioned above that failed to reach Syria in 2014. A mission to Erbil in Iraqi Kurdistan in 2015, headed by GNRD "High Commissioner" Lizin, appears to have been more successful. After the group's return, GNRD facilitated presentations by PYD members at a lunch for "decision-makers" in Brussels and at UN headquarters in Geneva.

GNRD and Palestine

GNRD's connections with Palestine were no less intriguing than those with the UAE – and possibly even more significant in the light of claims that GNRD was a Palestinian front organisation.

In 2012 some documents – allegedly part of a classified report prepared by the Palestinian Authority's external security department – appeared briefly on the website of the PA’s official news agency, Wafa, but were hastily deleted.

The report claimed that western countries were using Amnesty International, Human Rights Watch and similar organisations as a “striking arm” to influence policies around the world and remove governments from power. It proposed that the Palestinian Authority should have its own “striking arm” and named GNRD as the vehicle for this.

The Jerusalem Post reported at the time:

"The plan envisages using GNRD as a front for the establishment of an “effective and credible international human rights group that would operate from Geneva and whose goal would be to defend Palestinian causes” and collect information. The cost of the project is estimated at hundreds of millions of dollars."

Palestinian officials claimed the documents were fakes planted on Wafa's website by hackers. Other Palestinian sources cited by the Jerusalem Post claimed they were genuine and had been leaked by Mohammed Dahlan, the former head of “preventive security” in Gaza, along with Muhammad Rashid, a former financial adviser to Yasser Arafat, to discredit Mahmoud Abbas, the Palestinian president.

Whether the documents were authentic or not, GNRD did have several characteristics of a front organisation – not least in its opaque funding, its efforts to gain acceptance through cooperating with more normal organisations and the way it sought to play down its extensive Palestinian connections.

For example, Deeb's biography on Wikipedia claimed that as a teenage activist in Gaza he had been imprisoned and tortured by Israel. After moving to Norway had also been active on Palestinian issues, including the unsuccessful attempt to prosecute Israelis for war crimes.

Another GNRD board member – and its director of operations in Brussels – was Ramadan Abu Jazar, a Belgian citizen of Palestinian origin and head of the Palestinian House organisation in Belgium. He had previously brought a lawsuit against the Belgian government for failing to prevent the import or sale of Israeli settlement products in Belgium.

Despite both men's strong links with Palestine there was no mention of them in their profiles on the GNRD website. Deeb's profile simply said:

"PhD in International Law. 15 years of activities in the field of human rights. Member of many lawyers associations, such as in Cairo, Paris, London. Fellow of the Academy of European Law in Germany. Member of the Union for the ICC in Lahaye 'Den Haag'."

The image cultivated on its website was of an organisation concerned about Palestine – as most rights groups are – but not in an obsessive or strident way. Among the 2,500 pages on its website only 44 contained the word "Palestine". Many of those mentions were just incidental and most of the others were relatively bland, such as a report of GNRD youth groups attending an Easter service at a church in Gaza and carrying white flowers "to symbolise peace and religious tolerance between Muslims and Christians in Palestine".

This was fitted with GNRD's desire to be viewed as "neutral and impartial" but there were a few cracks in the facade. Some of its less-publicised activities relating to Palestine were far more politicised. For example, GNRD had produced a hard-hitting report on Israeli violations in the Gaza buffer zone which it circulated at the UN Human Rights Council. The 19-page document, compiled in collaboration with a Palestinian organisation, Al-Dameer Association for Human Rights, could also be found on GNRD's web server, but not as a normal part of the website. It had been tucked away in a folder labelled "userfiles".

For whatever reason, GNRD seemed anxious to avoid public controversy regarding its Palestine activities, and when NGO Monitor (a pro-Israel organisation) raised complaints about anti-Israel bias at two meetings held by GNRD on the sidelines of the UN Human Rights Council, GNRD responded by deleting reports of those events from its website.

Intelligence connections